Nasalis larvatus (van Wurmb, 1787)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863434 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFA7-FFA3-FAEF-635FF809F871 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Nasalis larvatus |

| status |

|

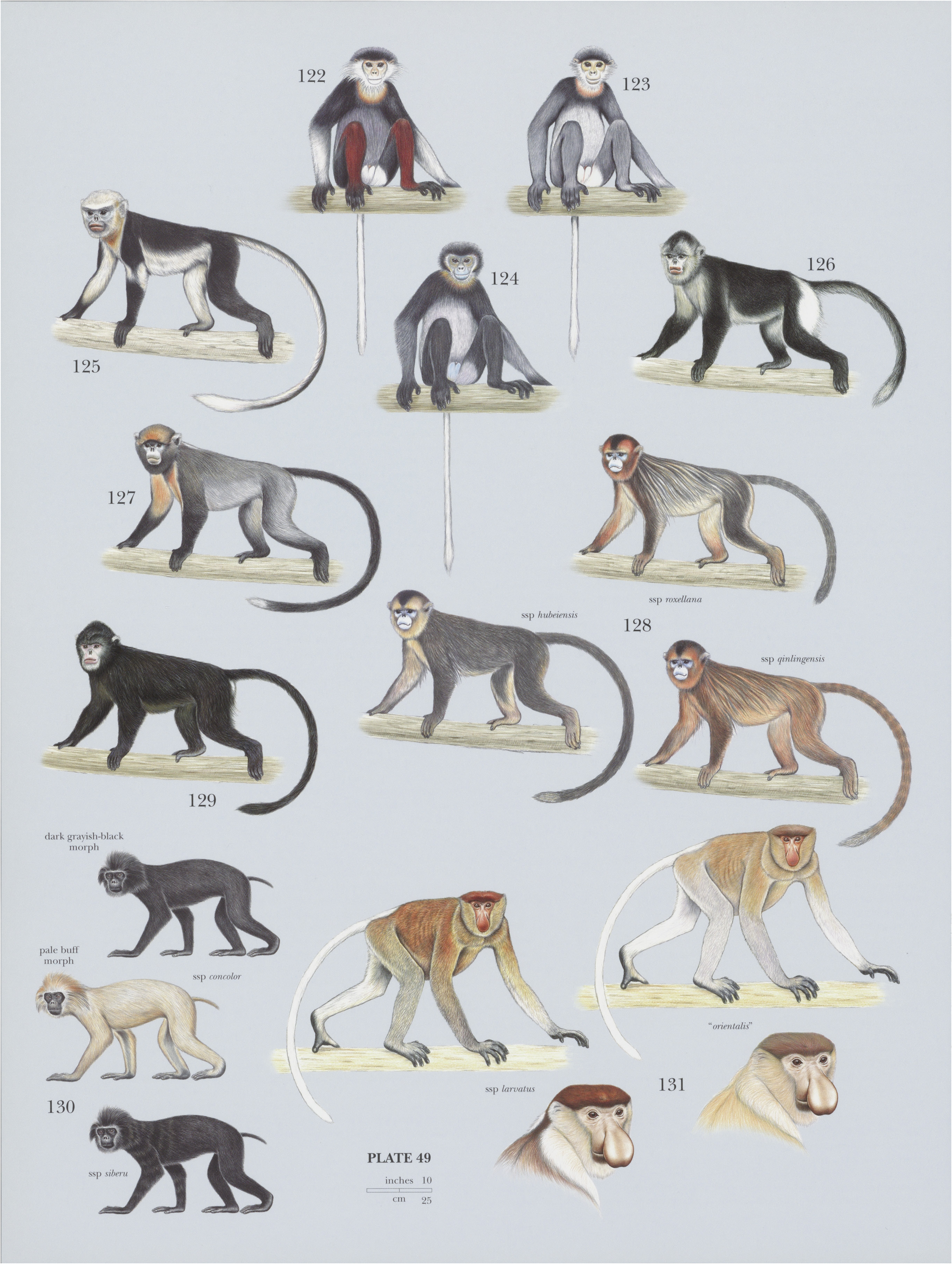

131. View Plate 49: Cercopithecidae

Proboscis Monkey

French: Nasigue / German: Nasenaffe / Spanish: Nasico

Other common names: Long-nosed Monkey

Taxonomy. Cercopithecus larvatus van Wurmb 1787 ,

Pontiana (=Pontianak), Borneo.

Two subspecies of N. larvatus are sometimes recognized: larvatus and orientalis. There is little difference between them, however, and the latter is not recognized by all authorities. Monotypic.

Distribution. Borneo (Sabah and Sarawak states, Brunei, and Kalimantan); it is also found on the satellite islands of Berhala, Sebatik, and Pulau Laut. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 73-76 cm (males) and 61-64 cm (females), tail 66 67 cm (males) and 55-62 cm (females); weight 20-24 kg (males) and c.10 kg (females). The Proboscis Monkey is strongly sexually dimorphic. It is a highly distinctive large, predominantly chestnut-brown monkey, with bare pink to brown faces. Ventral fur is paler than dorsal fur , except around sides of face and an almost complete yellowish collar around neck. Lower limbs, hands, and feet are gray. Stomach is relatively twice as large as any other species of colobine, so its abdomen appears bloated. The male is especially striking with his uniquely enormous, pendulous nose, dark chestnut cap, thick darker brown fur across upper and middle back and sides, and white rump patch and tail. The female has a smaller, “snubbier” nose, and her body is more uniformly brown, but with a gray rump patch and tail. Neonates have sparse, blackish fur and blue faces, with snubby upturned noses; by c.4 months of age, fur has turned brown, but face retains a blue-gray tinge for up to a year. Proboscis Monkeys have long hind feet, with partially webbed digits.

Habitat. Almost exclusively in coastal forests and forests close to major rivers, especially mangrove, peat swamp, and riparian forests. Proboscis Monkeys occur farther inland immediately adjacent to large rivers in Kalimantan and in inland swamps of Danau Senatarum and Mahakam Lakes. It is never found above elevations of 350 m, except for extremely rare seemingly vagrant individuals. It also occurs in some lowland dipterocarp forests but only near to rivers. In all habitats, Proboscis Monkeys are rarely found more than c.1 km from a significant waterway. Formerly, they were widespread throughout most coastal forests of Borneo and possibly along most major rivers.

Food and Feeding. Studies of Proboscis Monkeys at three sites in different parts of Borneo concur that the diet predominantly comprises young leaves (38-66%) and unripe fruits and seeds (26-50%), with flowers only ¢.3%. They occasionally forage on tree bark and termite nests. In Kinabatangan, Sabah, Proboscis Monkeys feed on 188 different plant species. Diets vary seasonally in food item type and diversity, depending largely on availabilities of edible fruits and seeds. In Samunsam, Sarawak, when fruits in riparian forests are scarce, they feed predominantly on young leaves and shoots of Rhizophora (Rhizophoraceae) species in mangroves.

Breeding. Proboscis Monkeys give birth to single offspring after a gestation of ¢.166 days. Sexual maturity is reached at 3-5 years in females and 5-7 years in males. Individual females generally breed every other year. In the wild, births can occur throughout the year but with a pronounced peak during the rainy season in November—February. Infants andjuveniles commonly scream and display at mating adults, including pulling on a mating male’s leg or nose.

Activity patterns. The Proboscis Monkey is diurnal, arboreal, and sometimes terrestrial. In almost all parts of their distribution, they spend the night in trees immediately adjacent to significant waterways, moving up to 750 m inland during the day; they return by late afternoon to a river prior to sleeping there for the night. As different groups move toward and assemble beside a river in the evenings, adult males give frequent spectacular displays, leaping between trees often with loud roars and landing with a noisy crash. One exception is at Bako National Park, Sarawak, where individuals spend the night in trees on cliffs slightly inland, moving down to mangrove bays in the early morning. Activity throughout the day largely comprises feeding periods interspersed with prolonged resting/digesting periods.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Daily movements of Proboscis Monkeys are determined strongly by the distribution of waterways, and their sleeping sites are generally beside open water. Predators include crocodiles (Crocodylus), Diard’s Clouded Leopards (Neofelis diardi), and reticulated pythons (Python reticulatus). Where waterways are narrow, Proboscis Monkeys traverse them by arboreal routes. They are also proficient swimmers. For widerrivers, they leap from a high branch into the river and then swim the final stretch or, for the wider rivers, climb down to the bank and slip into the water to swim across, with infants and females generally in front and the male farther behind. Proboscis Monkeys can swim considerable distances under water if disturbed. Data on daily movement patterns of individual groups are scarce, but they generally travel less than 1000 m. Home range sizes vary between sites, depending on habitat type and distribution of waterways. In heterogeneous lowland and mangrove forests of Samunsam, Sarawak, home ranges are c.9 km? whereas in the peat swamp forests Tanjung Puting, Kalimantan, they are 1-4 km®, in both cases encompassing forest on both sides of the river. Proboscis Monkey groups are non-territorial, with more than 90% home range overlap. Social groups comprise a single adult male and up to nine adult females and their offspring. Ranges of these unimale—multifemale groups overlap, and they frequently aggregate, especially beside rivers in the evenings. Both males and females transfer between groups. Males leave their natal groups at c.2 years of age and generallyjoin all-male groups, which in most cases are of similar size as unimale—multifemale groups. Infanticide has never been recorded, but occasional movements of females with dependent infants out of their unimale-multifemale groups indicate that it might occur.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Proboscis Monkeys are fully protected by law in all of the Bornean states where they occur, although enforcement is often weak. Coastal lowlands and land adjoining large rivers, which are the original habitats of the Proboscis Monkey, are the most developed areas of Borneo: most people live along rivers, most large towns are near river mouths, and most large-scale agriculture and aquaculture schemes are on coastal and alluvial plains. Few large, intact areas of suitable habitat remain, and populations of Proboscis Monkey are now highly fragmented and scattered; in Sabah, only an estimated 9-8% of the original suitable habitat remains. Of the remaining habitat, mangroves in many areas have been subjected to intensive logging for poles and charcoal. Peat swamp forests have also been heavily and repeatedly logged in many areas. In the 1970s and 1980s, such logging was sometimes followed by poisoning of non-timber trees, many of which were food trees for wildlife, with the aim of enhancing the next timber crop. This practice has been discontinued, but it was responsible for major degradation of some peat swamp forests. Forest fires along rivers can be damaging; e.g. the 1997-1998 Bornean fires destroyed large areas of remaining habitat. Hunting in the past might have been significant in some areas, potentially accounting for the limited and patchy distribution of the Proboscis Monkey along major rivers. In coastal areas, traditionally, hunting was not a significant problem because inhabitants are predominantly Muslims who do not eat monkeys. With the advent of speedboats and shotguns, however, people now come from towns to hunt Proboscis Monkeys for sport; their habit of sleeping conspicuously next to rivers makes them easy targets. Intense pressure on coastal land means that few reserves are large enough to protect whole populations, and the current status of the Proboscis Monkey is not well known. It is thought to occur in 18 protected areas, although all but five are too small, or habitat too marginal, to fully protect their populations. The protected areas are: Samunsam Reserve, Bako National Park, Kuching Wetland National Park, Sedilu National Park, Maludam National Park, and Rajang Mangrove National Park in Sarawak, Malaysia; Pulau Siarau & Pulau Beramban Primary Conservation Areas and Bukau Api Api Protection Forest Reserve in Brunei Darussalam; Maliau Basin Conservation Area, Danum Valley Conservation Area, Sepilok Orang Utan Sanctuary, Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Reserve, and Kulamba Wildlife Reserve in Sabah, Malaysia; and Kutai National Park, Pleihari Tana Laut Wildlife Reserve, Tanjung Puting National Park, Gunung Palung National Park, and Danau Sentaram National Park in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Recent estimates indicate that 6000 Proboscis Monkeys remain in Sabah, mostly in disjunct populations in the Kinabatangan and Segama river floodplains, with a smaller, fragmented population on the Klias Peninsula on the west coast. In Sarawak, less than 1000 individuals remain in patchily distributed populations. Proboscis Monkeys are more abundant in Kalimantan, with population sizes of 100-1000 individuals, although recent surveys are lacking. The population in the Mahakam Delta, which would have numbered in the thousands until the early 1990s, has been decimated because of conversion of the coastal swamps to shrimp farms. The Proboscis Monkey is now extinct in Indonesia’s Pulau Kaget Nature Reserve where it was once abundant.

Bibliography. Bennett (1988a), Bennett & Sebastian (1988), Boonratana (2000, 2002), Brandon-Jones et al. (2004), Chasen (1940), Groves (1989, 2001), Liedigk et al. (2012), Meijaard & Nijman (1999, 2000), Meijaard et al. (2008), Napier, J.R. & Napier (1985), Napier, P.H. (1985), Schultz (1942), Sha, Bernard & Nathan (2008), Sha, Matsuda & Bernard (2011), Yeager (1989, 1990, 1992).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.