Semnopithecus hypoleucos, Blyth, 1841

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863444 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFAA-FFA8-FA3E-6341FDD8F5F9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Semnopithecus hypoleucos |

| status |

|

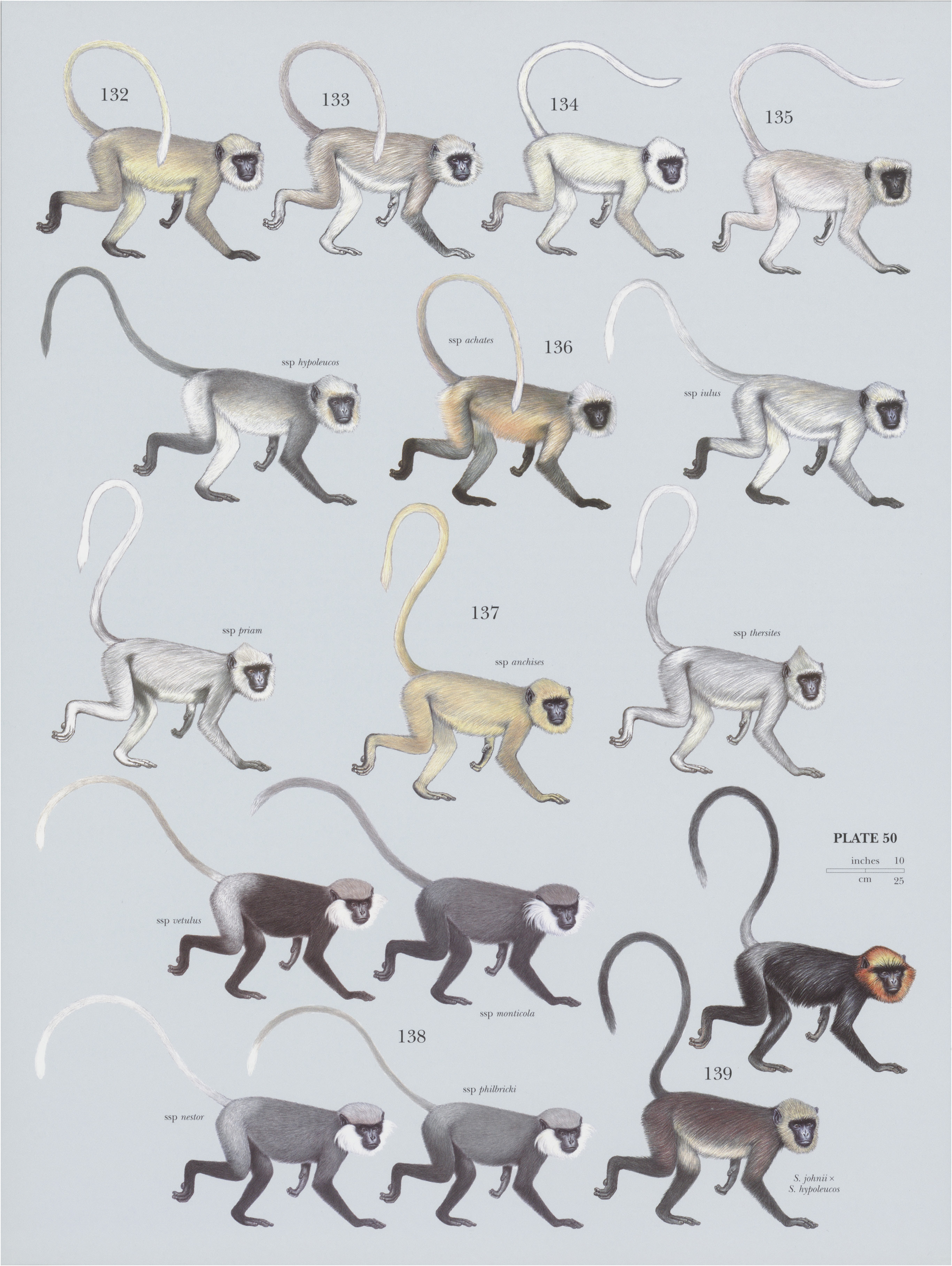

136. View Plate 50: Cercopithecidae

Malabar Sacred Langur

Semnopithecus hypoleucos View in CoL

French: Langur de Malabar / German: SchwarzfuR-Hulman / Spanish: Langur de pies negros

Other common names: Black-footed Gray Langur, Dark-legged Malabar Langur, Malabar Gray Langur; Black-legged Langur (julus), Northern Malabar Langur (achates), Travancore Langur (hypoleucos)

Taxonomy. Semnopithecus hypoleucos Blyth, 1841 View in CoL ,

India, Travancore.

In his 1939 review of the Asian langurs, W. C. O. Hill listed six subspecies: hypoleucos , aeneas, lus, dussumaieri, achates, and elissa. C. P. Groves in 2001 considered aeneas to a be junior synonym, and dussumieri to be a distinct species, with ulus, achates, and elissa as synonoms. Groves’s research since that time has led him to believe that these forms (including dussumieri) require further study and that together they might result in at least one distinct subspecies of S. hypoleucos . M. L. Roonwal separated gray langurs of South Asia into a northern group and a southern group based on tail carriage. S. hypoleucos is of the southern group (Type IIA), with the tail held up and back, and the distal half to one-third dangling. Independent studies, based on mtDNA and nuclear DNA of the southern group of Hanuman Langurs, indicated that three subspecies are valid taxa. Three subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

S. h. wulus Pocock, 1928 — SW India (Western Ghats), from Jog Falls in Karnataka State, at 440 m, and S along the hilly wet zones to the Brahmagiri Hills. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 52-68:6 cm, tail 73-109.2 cm; weight 13.6-15.9 kg (males) and 10.7-12.2 kg (females) for the “Northern Malabar Langur” (S. A. achates); head-body 50.8-55.5 cm, tail 72:5-91.4 cm; weight 9-5 kg (males) and 8-4 kg (females) for the “Black-legged Langur” (S. A. iulus). Dorsum of the Malabar Sacred Langur is a deep mauve-brown, and undersides are pale orange. Limbs are black below elbows and knees. Reported exceptions include a population with pale upper arms. Yellowish-brown head has crown hairs that slope up at the front and smooth down at back end of head. Face and ears are black, and eyebrows are long and bristle-like. Tail is black, with a few white hairs at the tip.

Habitat. Moist deciduous, riparian forests, sacred groves, and gardens at elevations of 100-1200 m. The Black-legged Langur and the “Travancore Langur” (S. A. hypoleucos ) are specialized denizens of wet-evergreen and semi-evergreen montane forests. The Northern Malabar Langur occurs in drier areas and in plains from sea level to 700 m.

Food and Feeding. Malabar Sacred Langurs are folivorous, but when leaves are scarce, they eat flowers, buds, bark, and fruit. At Dharwar in the state of Karnataka , they spend 58% of their time feeding on leaves, 29% seeds and fruits, 7% flowers, 2% buds and bark, and 4% other items such as insects. They eat leaf galls on Terminalia tomentosa (Combretaceae) and small black caterpillars. Water sources dry up in the dry season, but they can survive without drinking water for 4-5 months at a stretch.

Breeding. Newborn Malabar Sacred Langurs are seen in most months but with a somewhat higher frequency in December—April. In each group, births occur mainly within 2-6 months, but the months vary from group to group and from year to year. Infants are black and passed among females (allomothering). Males do not care for young, but the dominant male intervenes in defense of an infant when it is threatened (as it also does for any group member). Infants are weaned after ¢.20 months, and even 2year-old juveniles are sometimes seen suckling. Juveniles become completely independent of their mothers by three years of age. Infants are able to approach the dominant male, who tolerates and even plays with them.

Activity patterns. Malabar Sacred Langurs are diurnal and mainly terrestrial. They spend ¢.20-40% of the day on the ground. When on the ground, they move about ten times faster and about three times farther than when in trees.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. At Dharwar, the Northern Malabar Langur forms bisexual and all-male groups. Most bisexual groups have only one adult male (46 of 63 groups) and 6-9 adult females. Groups otherwise have 2-7 adult males, but many of them in this situation are believed to be undergoing a transition of male residence. Six bisexual groups studied at Dharwar were unimale—multifemale and contained 15-27 individuals. All-male groups contained 2-59 individuals. Bisexual groups have home ranges of 10-33 ha (average 18-6 ha). Home ranges of all-male groups overlap those of several bisexual groups. Adult males disperse and form allmale groups. Contacts among bisexual groups and all-male groups are generally aggressive and have been described as attacks. When the dominant male of a bisexual group sees an all-male group, he approaches and threatens them (grinding his teeth, biting the air, and display jumping, accompanied by “whoops” and belching). Often, the all-male group runs away, but sometimes males counterattack, resulting in flight or injury of the bisexual group’s male, and then the all-male group invades his group. Sometimes invading males leave the area after a few hours, and the group’s male,if not too injured, returns. Sometimes males that carry out a successful attack on a bisexual group drive out the resident adult, subadult, and sometimes juvenile males, or abduct the group’s adult and immature females, while killing the infants. The majority of attacks occur during the first half of the mating season. Population densities at Dharwar were very high at 85-134 ind/km* when Y. Sugiyama and K. Yoshiba carried out their studies there. All-male groups were common, and the frequency of social changes in bisexual groups was high. The two longest recorded male tenures at Dharwar were three and six years. The high densities possibly resulted from lack of predators and loss of habitat, concentrating individuals into a small area.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List, including the nominate subspecies, but the subspecies achates (under S. dussumier: achates) and ulus (under S. dussumieri iulus) are classified as Least Concern. The Malabar Sacred Langur is protected under Schedule II, Part II, of the Indian (Wildlife) Protection Act, 1972, amended up to 2002. The Travancore Langur occurs in Wyanad and Brahmagiri wildlife sanctuaries and Nagarhole National Park. The Black-legged Langur occurs in Kudremukh, Mollem, and Nagarhole national parks and Pushpagirl, Bhadra, Sharavati Valley, Anshi, Bondla, Mookambika, and Radhanagari wildlife sanctuaries. Hunting is a serious threat, particularly for the two western hill zone subspecies, the Travancore and Black-legged langurs. The Malabar Sacred Langur has been entirely extirpated from the eastern slopes of Coorg because of hunting. Other threats include fragmentation, habitat loss, local trade in live animals and meat, trade for use in traditional medicine, developmental activities, and change in land use for agriculture and mining. The Malabar Sacred Langur is the most poorly studied of the southern Indian langurs.

Bibliography. Bennett & Davies (1994), Groves (2001), Hill (1939), Hohmann (1988, 1989a), Karanth (2010), Karanth et al. (2010), Kirkpatrick (2011), Molur et al. (2003), Nag et al. (2011a, 2011b), Oppenheimer (1977), Roonwal (1984, 1986), Roonwal, Prita & Saha (1984), Sugiyama (1965a, 1965b, 1966), Sugiyama (1967), Sugiyama et al. (1965), Yoshiba (1967, 1968).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Semnopithecus hypoleucos

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Semnopithecus hypoleucos

| Blyth 1841 |