Ningaui timealeyi, Archer, 1975, Archer, 1975

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602855 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF87-246B-FAC0-FEE50A460484 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Ningaui timealeyi |

| status |

|

53. View On

Pilbara Ningaui

French: Ningaui du Pilbara / German: Pilbara-Ningaui / Spanish: Ningaui de Pilbara

Other common names: Ealey’s Ningaui, Pibor Ningaui

Taxonomy. Ningaui timealeyi Archer, 1975 View in CoL ,

32.2 km SE Mt. Robinson, Western Australia, Australia.

M. Archer described the genus Ningau: in 1975, and he simultaneously described two species: N. timealeyi (from the Pilbara region in Western Australia) and N. ride : (from central Western Australia). The genus evidently has greatest similarity morphologically and genetically with dunnarts (genus Sminthopsis ), differing from them in structure of lateral wall ofskull, structure and width of hindfoot ( Ningaui have broader feet than Sminthopsis but narrower than Planigale ), more reduced cusps on upper molar teeth, and generally smaller size. In a subsequent (1983) genetic study on the genus, allozyme electrophoresis indicated ningauis fell into three groups, with large differences between groups (21-32% fixed differences) and homogeneity within groups. One group from the Pilbara of Western Australia was identified as N. timealey; a second group extending from the Kalgoorlie area of Western Australia to the far west of South Australia and north to the Tanami Desert of the Northern Territory was identified as N. rides; a third group extending from the Kalgoorlie area of Western Australia (where it is sympatric with N. ridei ) across southern South Australia and into northwestern Victoria was identified as N. yvonneae, a species that had only been formally described that very year on the basis of skull morphology. Recent genetic (mtDNA and nDNA) studies have consistently resolved monophyly for Ningaui , but the genus Sminthopsis was not resolved as monophyletic with respect to Ningaui (or indeed Antechinomys ). In the combined DNA phylogeny, Ningaui was poorly resolved as sister to the “ Macroura ” group of Sminthopsis (five species), and this combined clade was a poorly resolved sister to the remaining species of Sminthopsis (13 species), with the exception of S. longicaudata , which was strongly supported as sister to A. laniger . Within Ningaua, N. timealeyi was consistently resolved as a well-supported sister of a clade containing N. ridei and N. yvonneae. These genetic relationships concord with morphology, where N. timealeyi can be distinguished from congeners by size and shape of footpads, nipple number in females, and some skull features, whereas N. ride : and N. yvonneae are unfortunately indistinguishable externally. Monotypic.

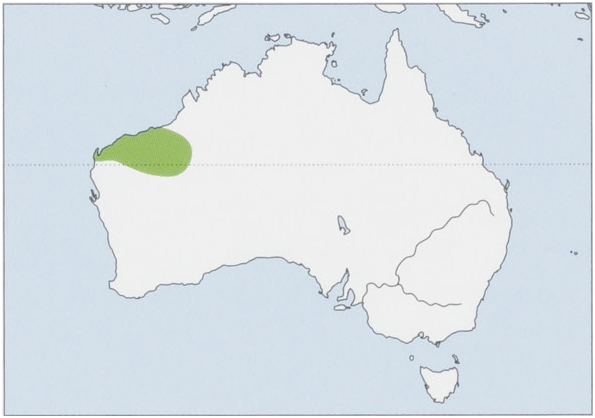

Distribution. Endemic to Western Australia, limited mostly to the Pilbara region (broadly distributed from the W coast through to C Pilbara, from the Cape Range to Telfer), but also found in the Gascoyne region and the Little Sandy Desert. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 5:6.7-6 cm (males) and 5:6.6-5 cm (females), tail 6.3-9.5 cm (males) and 5.7-6.8 cm (females); weight 3-6-9-5 g (males) and 3-5-7-5 g (females). There is mild sexual dimorphism for size. The Pilbara Ningaui differs from planigales in having long bristly fur on a rounded head rather than shorter fur on a flat head. Pelage of the Pilbara Ningauiis gray overall, distinguishing it from the Wongai Ningaui ( N. ridei ), which has a reddish-brown pelage around head. The Wongai Ningaui has smaller (less than 1 mm long), oval-shaped pads on rear of hindfeet than those of the Pilbara Ningaui ( N. timealeyi ) in which pads are longer than wide (more than 1 mm long). These species also apparently have a different number of nipples: six in the Pilbara Ningaui and seven in the Wongai Ningaui. The two species are sympatric in some areas; however, the Pilbara Ningauiis mostly confined to the Pilbara region in Western Australia, whereas the Wongai Ningauiis not found in the Pilbara.

Habitat. Outwash plains near ridges and outcrops, along drainage lines where moisture supports growth of large, dense hummocks of spinifex (7riodia spp., Poaceae ), low shrublands and woodlands (mallees), trees, or scattered shrubs. The Pilbara Ningaui occurs on ridge tops and sand plains and in areas of snakewood ( Acacia xiphophylla , Fabaceae ) over grass on clay. One study found that preferred habitat of the Pilbara Ningaui was dense to moderately dense hummock grassland, particularly with an upper stratum of open mallee or scrub.

Food and Feeding. The Pilbara Ningauiis a ferocious predator. It preys on centipedes and cockroaches, but its prey also includes larger animals that must be subdued with a struggle. In captivity, it eats cockroaches, centipedes, grasshoppers, crickets, and small skinks, but it will ignore beetles and millipedes. Captive Pilbara Ningauis drink water, but in the wild, most water is probably obtained from prey and, if necessary, supplemented by licking dew.

Breeding. Following a good season, sexual maturity of Pilbara Ningauisis attained by late winter, and females have young in the pouch in September-March when most annual rainfall occurs. Females have 4-6 teats arranged in a concentric ring within the pouch, which is a simple depression on the belly lacking fur. Typically, 5-6 young are carried in the pouch to weaning. Young become independent at ¢.2 g in weight.Juveniles are found in trappable populations from late December until May. During the breeding period, males are aggressive toward each other, and females with pouch young will drive away other adults. By March in most years, populations consist predominantly of independent young. Individuals of both sexes can survive to a second breeding season, but adults are likely less mobile than young in autumn. In one study of museum specimens, Pilbara Ningauis reached sexual maturity in their first year, and after the end ofJuly of each year, almost all males were considered reproductively mature. Male Pilbara Ningauis in the active spermatogenic phase were found in August—January; testes had regressed to an immature spermatogenic stage after January. There was no indication that adult males died immediately following mating, as in species of Antechinus and Phascogale . In another study, measurements of maximal scrotum width for males trapped in each of five sampling periods suggested that males reached peak sexual developmentin spring (September—October). After this time, malesstill in the population showed a decline in gonadalsize. Young were produced in spring and summer, with pouch young appearing as early as September and females still lactating in late March the following year. Litters consisted of 4-6 pouch young. Individuals caught in March consisted predominantly ofjuveniles; few surviving adults were captured from the previous year. Adults from the previous year were unlikely to have reproduced a second time. By September—October, all Pilbara Ningauis trapped were adults; males had reached peak breeding condition, and some females had developed pouches or were carrying pouch young.

Activity patterns. By day, hummocks provide Pilbara Ningauis shelter and refuge; by night, they hunt on the ground in more open spaces, scrambling among branches and stems of shrubs. In captivity, Pilbara Ningauis exhibit alternating periods of activity and inactivity, day and night. In the wild, daylight activity is probably restricted to grooming and defecation within, or near, refuge areas. Interestingly, there is no evidence of torpor.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Pilbara Ningaui is aggressive when handled and will often bite; it rarely emits an audible noise in captivity. It is often the most commonly trapped mammal in surveys in Pilbara. It is usually caught in pittraps, will enter funnel-traps, and has even been caught in Elliott traps. In one study conducted in the Hammersley Ranges (eastern Pilbara), an impressive 156 individual Pilbara Ningauis were trapped acrossall six localities surveyed.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Pilbara Ningaui has a wide distribution and presumably a large overall population; it does not face any major conservation threats. The Pilbara Ningaui is present in Karijini (= Hamersley Range) and Millstream-Chichester national parks. It is also found in the Meentheena pastoral lease station, which may be converted into a conservation area. In dry years with low reproductive success, Pilbara Ningauis may survive only in pockets of moister habitat refuges, later recolonizing from there.

Bibliography. Archer (1975), Baverstock et al. (1983), Burbidge (2008), Dunlop & Sawle (1982), Dunlop et al. (2008), Kitchener, Cooper & Bradley (1986), Kitchener, Stoddart & Henry (1983), Krajewski et al. (2012).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Ningaui timealeyi

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Ningaui timealeyi

| Archer 1975 |