Murexia naso (Jentink, 1911)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602829 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF8F-2462-FFCA-F90306D00BE4 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Murexia naso |

| status |

|

42. View On

Long-nosed Dasyure

French: Murexie a long museau / German: Langnasen-Neuguinea-Beutelmaus / Spanish: Dasiuro de hocico largo

Other common names: Long-nosed Antechinus

Taxonomy. Phascogale naso Jentink, 1911 ,

south of Mt. Wilhelmina , about 2000 m, 4° 32° S, 138° 41’ E, Helwig Mountains , Jayawijaya Div., Prov. of Papua (= Irian Jaya), Indonesia. GoogleMaps

Acceptance of Antechinus occurring in both Australia and New Guinea lasted throughout much of the 20™ century. Then, in 1984, P. A. Woolley’s studies of male penile morphology indicated a dubious relationship between Australian and New Guinean members of Antechinus . Antechinus in Australia were by then no longer considered monophyletic, including what is now regard as Dasykaluta rosamondae , Pseudantechinus macdonnellensis , P. ningbing , P. bilarni , and Parantechinus apicalis . This was followed by work clarifying species applicable to the “antechinus” of New Guinea ( melanurus , habbema, and naso ). It was agreed that New Guinean taxa needed reclassification—they were clearly not Antechinus . DNA hybridization and albumin immunology studies confirmed the closer relationship among New Guinean species than with Australian Antechinus . Subsequent direct DNA work suggested that New Guinean taxa were sister to Australian antechinuses. In 2002, S. Van Dyck’s detailed morphological study of both Australian and New Guinean “antechinuses” concluded that New Guinea taxa assigned to Antechinus (pre-1984) represented three related but morphologically primitive taxa that lacked clear signs of relationship to each other. They were thus referred to five genera. Monotypic Micromurexia (habbema), Phascomurexia ( naso ), and Murexechinus ( melanurus ) were all only distantly related to Australian antechinuses; New Guinean Murexia was thus rendered also monotypic ( M. longicaudata ) and morphologically, this taxon was viewed as having no especially close relationship with the more derived rothschildi , which was thus assigned to a fifth genus, Paramurexia . Nevertheless, in the last decade, there have been independent DNA sequencing studies that consistently recover monophyly of Murexia with respect to other Phascogalines, Australian genera Antechinus and Phascogale , with uncertain status ofsister relationships between the three. This is today’s prevailing view, so a single genus ( Murexia ) for New Guinean fauna is cautiously adopted here. F. A. Jentink in 1911 named what we now know as M. naso in recognition of the specimen’s fluted, raised nasals of the skull. Thereafter, astonishingly, the holotype was not mentioned again until 1954 by E. M. O. Laurie and J. E. Hill. In the interim, G. H. H. Tate and R. Archbold, apparently unaware of the naso holotype, and also that nasal condition could be quite variable, named fafa and subsequently centralisin 1941 (as a subspecies of tafa) without association to naso . Later, in 1947, Tate submerged fafa and centralis into subspecies under G. Dollman’s mayeri, despite the fact that Dollman himself had indicated he felt mayeri was most similar to M. melanurus . Further confusion followed when Tate added another subspecies under mayeri, coined misim. Tate acknowledged all three mayer: subspecies (tafa, centralis, and misim) were externally indistinguishable and might indeed be merged in subsequent reviews but maintained their status based on tooth and skull variations. Then, in 1954, Laurie and Hill finally equated Jentink’s naso with Tate’s triumvirate of mayer: subspecies. In 1995, T. Flannery listed four subspecies in reference to the work of Dollman and Tate, and they are herein retained, but theirstatus is now surely uncertain. Like the other Murexia , M. naso needs revision using comparative morphological and genetic data; genetics of specimens from a variety of locations throughout the species’ distribution will be required. Nevertheless, difficulty in obtaining such specimens because of New Guinea's remoteness and lower catch rates of New Guinean dasyurid fauna, has thwarted earnest efforts to clarify taxonomic uncertainties to date and will continue to pose challenges into the future. Four subspecies recognized.

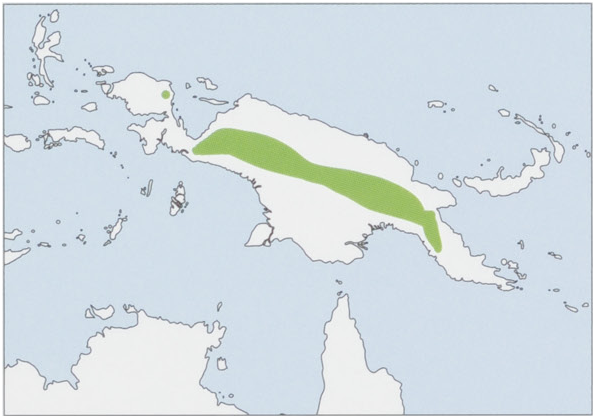

Subspecies and Distribution.

M. n. nasoJentink, 1911-W New Guinea Central Range in Papua Province, Indonesia.

M.n.mayer:Dollman,1930—NWNewGuinea,Bird’sHead(=Vogelkop)Peninsula.

M.n.misimTate,1947—ENewGuineaCentralRangeinPapuaNewGuinea.

M. n. tafa Tate & Archbold, 1936 — SE New Guinea. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 11:4-14.5 cm (males) and 10.6-13.4 cm (females), tail 10-5—17-5 cm (males) and 11:4-16.4 cm (females); weight 42-74 g (males) and 29-48.5 g (females). The Long-nosed Dasyure could be confused with the Black-tailed Dasyure ( M. melanurus ), but it has a less hairy tail, the last few centimeters of which are usually whitish.

Habitat. Rainforest, mid-montane forest, beech forest, pandanus forest, and mossy forest at elevations of 1400-2800 m.

Food and Feeding. In one study, 33 (21 male and twelve female) Long-nosed Dasyures caught at Mount Kaindi produced feces that contained, by percent frequency of occurrence in feces examined, 85% beetles, 85% grasshoppers and crickets, 74% spiders, 41% bugs, 36% unidentified insects, 18% worms, 15% cockroaches, 12% moths and butterflies, and 9% flies.

Breeding. One study of seven (five male and two female) wild-caught Long-nosed Dasyures suggested that it breeds at any time of the year, supported by incidence of lactating females, often at different stages of lactation, in most months when adult females were captured, together with the incidence ofjuveniles in the population. No litters were successfully bred in captivity, despite three attempted pairings. Females had four nipples and mothers carried 2—4 young; pseudopregnancy lasted 26-33 days. Male Long-nosed Dasyures have sternal glands and scrotal widths of 12-14-5 mm. Males mature at c.14 months. Lactating females have been collected in January, February, April, May, June, August, September, and December.

Activity patterns. The Long-nosed Dasyure is crepuscular and probably partly arboreal. In one study, eight individuals were trapped, and two were captured by hand from tree trunks at night. The eight individuals from traps were caught within 3 m of the ground (four on logs or branches, and the remainder on the ground), and traps were baited with sweet potato, oil, or meat.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. In one study using spool-and-line tracking, a single adult male LLong-nosed Dasyure was tracked to its nest in an area on Mount Kaindi. The L-shaped tunnel led to a nesting chamber c¢.65 cm under the surface. The chamber was ¢.20 cm in diameter and heavily lined with dry leaves. The male covered a distance of 157 m from trap site to its nest, on the way climbing 2 m up a tree and 4 m up a liana into a tree fern.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Longnosed Dasyure has a wide distribution, presumably a large overall population, and lacks the threat of major conservation threats. It is unlikely to be declining at nearly the rate required to qualify for listing in a threatened category. Long-nosed Dasyures occur in several protected areas.

Bibliography. Armstrong et al. (1998), Dollman (1930), Dwyer (1977), Flannery (1995a), Grossek et al. (2010), Groves (2005a), Helgen (2007a, 2007b), Helgen & Opiang (2011), Jentink (1911), Krajewski, Torunsky et al. (2007), Krajewski, Wroe & Westerman (2000), Krajewski, Young et al. (1997), Laurie & Hill (1954), Leary, Seri, Wright, Hamilton, Helgen, Singadan, Menzies, Allison, James, Dickman, Lunde, Aplin & Woolley (2008d), Menzies (1991), Tate (1938, 1947), Tate & Archbold (1936, 1937 1941), Van Dyck (2002), Woolley (1984b, 1989, 2003).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Murexia naso

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Phascogale naso

| Jentink 1911 |