Dasyurus hallucatus, Gould, 1842

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602777 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FFB8-2456-FF13-F3DB0C280D57 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Dasyurus hallucatus |

| status |

|

21. View On

Northern Quoll

Dasyurus hallucatus View in CoL

French: Quoll nain / German: Noérdlicher Beutelmarder / Spanish: Dasiuro septentrional

Other common names: Little Northern Native Cat

Taxonomy. Dasyurus hallucatus Gould, 1842 View in CoL ,

Northern Territory, Port Essington, Northern Territory, Australia.

J. Gould in 1842 described D. hallucatus , just a year after publishing the description of D. geoffroui. Four subspecies of D. hallucatus were subsequently recognized based on morphological differences and geographical locations: nominate hallucatus in the Northern Territory, nesaeus in Groote Eylandyt, exilisin Western Australia, and predator in Cape York Peninsula (Queensland). Nevertheless, these subspecies are no longer recognized. Recent mitochondrial and nuclear genetic phylogenies indicate that the quoll group ( geoffroii , hallucatus , maculatus , and viverrinus ) form a monophyletic clade; the sister taxon to this group 1s evidently the Tasmanian Devil ( Sarcophilus harrisii ). In one study, D. hallucatus was positioned as sister to all other quolls. Although geographically D. hallucatus is proximate to D. spartacus from New Guinea, the two species are apparently deeply genetically divergent. Preliminary results from this study suggest strongly divergent lineages among D. hallucatus from Western Australia and those in the Northern Territory and Queensland; indeed, these groups of D. hallucatus were at least as divergent as that between D. geoffroii and D. spartacus . The two latter species are presently separated by several thousand kilometers and, even allowing for pre-European distributions of D. geoffroii , were apparently separated by the expanse of Cape York Peninsula and Queensland’s wet tropics. Further studies focusing on geographically disjunct populations of D. hallucatus suggest that a resurrected subspecific classification may be necessary. Monotypic.

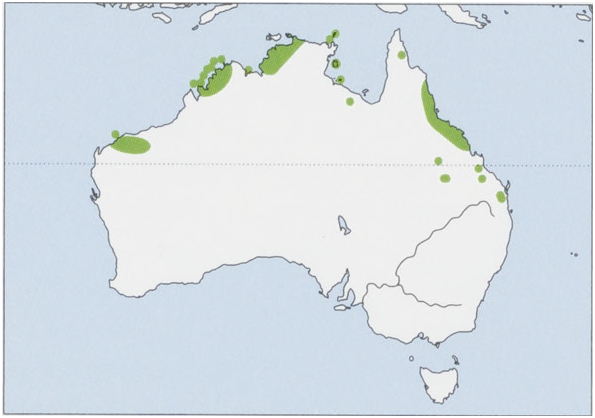

Distribution. N Australia, on several disjunct populations in W & N Western Australia (including Dolphin I, Buccaneer and Bonaparte archipelagos, and Adolphus I), N Northern Territory (including Channel, Marchinbar, Inglis, Groote Eylandt, Northeast, and Vanderlin Is), and N & E Queensland. Recently (2003) translocated to Astell and Pobassoo Is, Northern Territory. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 27-37 cm (males) and 24.9-31 cm (females), tail 22-2— 34-5 cm (males) and 20.2-30 cm (females); weight 0-34—1-1 kg (males) and 240-690 g (females). There is marked sexual dimorphism for size. The Northern Quoll is the smallest Australian quoll. Its body is brown with white spots on back, rump, and head; belly is creamy-white. Tail is brown at base, with occasional white spots; it has a dark brown or black tip with no spots.

Habitat. Dissected, rocky escarpments but also eucalypt forest and woodland, around human settlements, and sometimes in rainforest patches or on beaches. The Northern Quoll remains common in coastal parts of Kimberley and Top End where it may be observed scavenging around campgrounds at night. In Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, it may be quite common. In the northern two-thirds of the park, the Northern Quoll has been recorded in all major habitat types, being most abundant in open forest and rocky escarpment, but it is only rarely present in monsoon forest or woodland away from escarpment areas.

Food and Feeding. Northern Quolls are opportunistic omnivores. In savanna country, their diets typically include invertebrates, particularly beetles, grasshoppers, spiders, and centipedes, but they also evidently eat fruits from at least nine species of plants, particularly favoring the wild grape, Ampelocissus acetosa (Vitaceae) . Vertebrates consumed by Northern Quolls include atleast eleven species of mammals, including bandicoots, Sugar Gliders (Petaurus breviceps), Common Brush-tailed Possums (Trichosurus vulpecula), and rats, at least eight species of birds and reptiles (skinks and snakes), and at least seven species of frogs. Northern Quolls also eat bird eggs and nectar of eucalypt and evergreen grevillea ( Proteaceae ) flowers. In savanna country, their diets change seasonally, with invertebrate consumption peaking in September—February, fleshy fruit in March-April, and vertebrates in July-August. Northern Quolls also scavenge from road-kills and garbage bins. They will drink free water when it is available but can obtain sufficient moisture from their food when seasonal creeks have dried up.

Breeding During the mating period, male Northern Quolls regularly visit several females in succession to monitor onset of estrus. This intense physical effort appears to be at least a partial cause of physiological decline of males and subsequent die-off at one year of age in some populations, because captive males can live for up to six years. Northern Quolls breed once each year and exhibit synchronous reproduction within each year at each site. Females have 5-9 teats, but most females have eightteats. Pouch becomes deep and moist, and on average, seven young are born after gestation of 21-26 days. At 8-9 weeks old, the mother deposits her young in a series of nursery dens. She forages alone but returns regularly to allow young to suckle; at this stage, the mother’s pouch is stretched and teats are exposed. Juveniles begin to eat insects at c.4 months old, but they are not fully weaned until c.6 months old when their mother’s pouch everts to resemble an udder. Young are reproductively mature at c.11 months old. Northern Quolls have an extremely short life span, with most females only surviving one breeding season. Indeed, the oldest female recorded in the wild was c¢.3 years old. Despite males weighing up to 1-1 kg, all males in at least some populations die after mating; thus, the Northern Quoll is deemed facultatively semelparous. One interesting study focused on the birthing event in Northern Quolls. Parturition began with the release of c.1 mm of watery fluid from the urogenital sinus, followed by an exuded gelatinous material encasing newborn young. To exit this column of material, young had to grasp hair and wriggle c.1 cm across to the pouch. After young are in the pouch, they compete for a teat. Mothers had eight teats, but number of young born was as high as 17 in the six females under study.

Activity patterns. The Northern Quoll is predominantly nocturnal, but they are occasionally active during the day, particularly during the mating season or in overcast weather.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Northern Quolls are ground dwelling and arboreal, using a variety of den sites, including rock crevices, termite mounds, tree hollows, logs, roofs of houses, and goanna (monitor lizards) burrows. In savanna country, both sexes of Northern Quolls typically change dens nightly, with females each using up to 55 dens; however, den sharing is rare. Savanna populations are low in density; females occupy territories averaging 35 ha, preferring low, rocky hills. Home ranges of adult males are more than 100 ha and generally overlap with several home ranges of females and numerous males. Dissected escarpment zones support higher density populations. One study focused on radio tracking and live trapping at a lowland savanna site in Kakadu National Park; females occupied home ranges averaging 35 ha, with intrasexually exclusive denning areas. Male home range size may be similar to that offemales prior to the mating season, but it expands during the mating season to more than 100 ha, overlapping extensively with several female and numerous other male home ranges. Despite this overlap, both sexes are apparently solitary. Even during the mating period, males denned on average 0-27 km from females during the day. At this time, each female was visited by at least 1-4 males/night. An increase in deposition of feces in prominent positions in the landscape and simultaneous increase in sternal gland activity of males suggest reliance on olfactory communication to advertise presence and sexual status of individuals. Marked sexual dimorphism in the Northern Quoll may be the result of selection for larger, wider-ranging males in a promiscuous mating system and for energetically efficient, smaller females because mothers rear their young alone.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Listed as endangered in Australia. The Northern Quoll has experienced a serious population decline, estimated to exceed 50% over the last ten years. This trend is projected to continue at a similar rate over the next ten years based on effects of habitat destruction and landscape degradation, consumption of poisonous cane toads (Rhinella marina), and introduced predators. At the time of European settlement, the Northern Quoll was most likely distributed continuously across northern Australia from the Pilbara, Western Australia, to southern Queensland, but it is now limited to several disjunct populations in Queensland, Northern Territory, and Western Australia. In the present day, the Northern Quoll remains common in coastal parts of Kimberley, but in north Queensland,it appears to have undergone a decline during the past two decades. In the Cape York region around Coen, some park rangers believe it was common before 1980 but has since disappeared. In central Queensland,it still may be found in places like Carnarvon Gorge, but no recent records exist from southern Queensland. In eastern Kimberley, the Northern Quoll is only known from bones at Aboriginal camps, and it is now unknown from south-western Kimberley. There are records from the 1980s in the Bungle Bungles, but it was not recorded there during a recent comprehensive biological survey, and Aboriginal people have not seen it there for years. Owl pellets at roostsites suggest that the Northern Quoll was formerly common throughout Pilbara well into the arid zone. It can still be found in Litchfield, Nitmiluk, and Garig Gunak Barlu (= Gurig) national parks in the Northern Territory. Decline of the Northern Quoll has been directly associated with spread of an introduced poisonous prey species, the cane toad. Ahead of the imminent arrival of the cane toad in Western Australia proper, the Northern Quoll remains in the two regions it occupies there, Kimberley and Pilbara , but cane toads are rapidly infiltrating these areas. Radio tracking has shown that the most common direct cause of adult mortality in wild populations of Northern Quoll is predation by Dingoes (Canis lupus dingo), domestic and feral cats, snakes, owls, and kites. Removal of groundcover during fire increases their vulnerability to predation. Other causes of mortality include domestic dogs, motor vehicles, and pesticide poisoning. In areas that have been newly invaded by cane toads in the Northern Territory, Northern Quolls are poisoned when they try to eat the noxious amphibian; indeed, populations of Northern Quolls may become locally extinct within a year of cane toad contact. There are exceptions, however, and the mechanism that has allowed some remnant populations of Northern Quoll to persist in areas of Queensland where cane toads have long been present is unclear. Taken together, this research suggests the most critical conservation measure currently required for the Northern Quoll is amelioration of the impact of cane toads in Northern Territory and Western Australia. Short-term conservation measures include captive breeding programs and translocations of Northern Quolls. In 2003, Northern Quolls captured from wild populations in the Northern Territory mainland were translocated to Astell Island (1264 ha) and Pobassoo Island (390 ha). Extensive surveys had not detected the Northern Quoll on these islands prior to translocation. In 2008, a study assessed genetic health of these translocated populations. In the short term (over three generations), translocated populations exhibited a slight but non-significant reduction in genetic diversity compared with mainland source populations. Comparatively high genetic erosion was observed in endemic island populations. Genetic bottlenecks were detected in endemic islands and one mainland population, implying recent reductions in population size. Such results are consistent with numerous studies on vertebrates that have described greater losses of genetic diversity in island populations than mainland populations.

Bibliography. Braithwaite & Griffiths (1994), Cardoso et al. (2009), Firestone (2000), Gould (1842a), Hohnen et al. (2013), How etal. (2009), Nelson & Gemmell (2003), Oakwood (2000, 2002, 2004, 2008), Oakwood et al. (2001), Schmitt et al. (1989), Thomas (1909b, 1926), Ujvari et al. (2013).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Dasyurus hallucatus

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Dasyurus hallucatus

| Gould 1842 |