Servaea incana (Karsch, 1878), 2017

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5141.3.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F6CCED36-ECC2-4E4C-8943-8106597BCC79 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6592748 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EC5C87DB-6510-0463-2A86-6DF5FEA0DBCB |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Servaea incana (Karsch, 1878) |

| status |

|

Servaea incana (Karsch, 1878) View in CoL

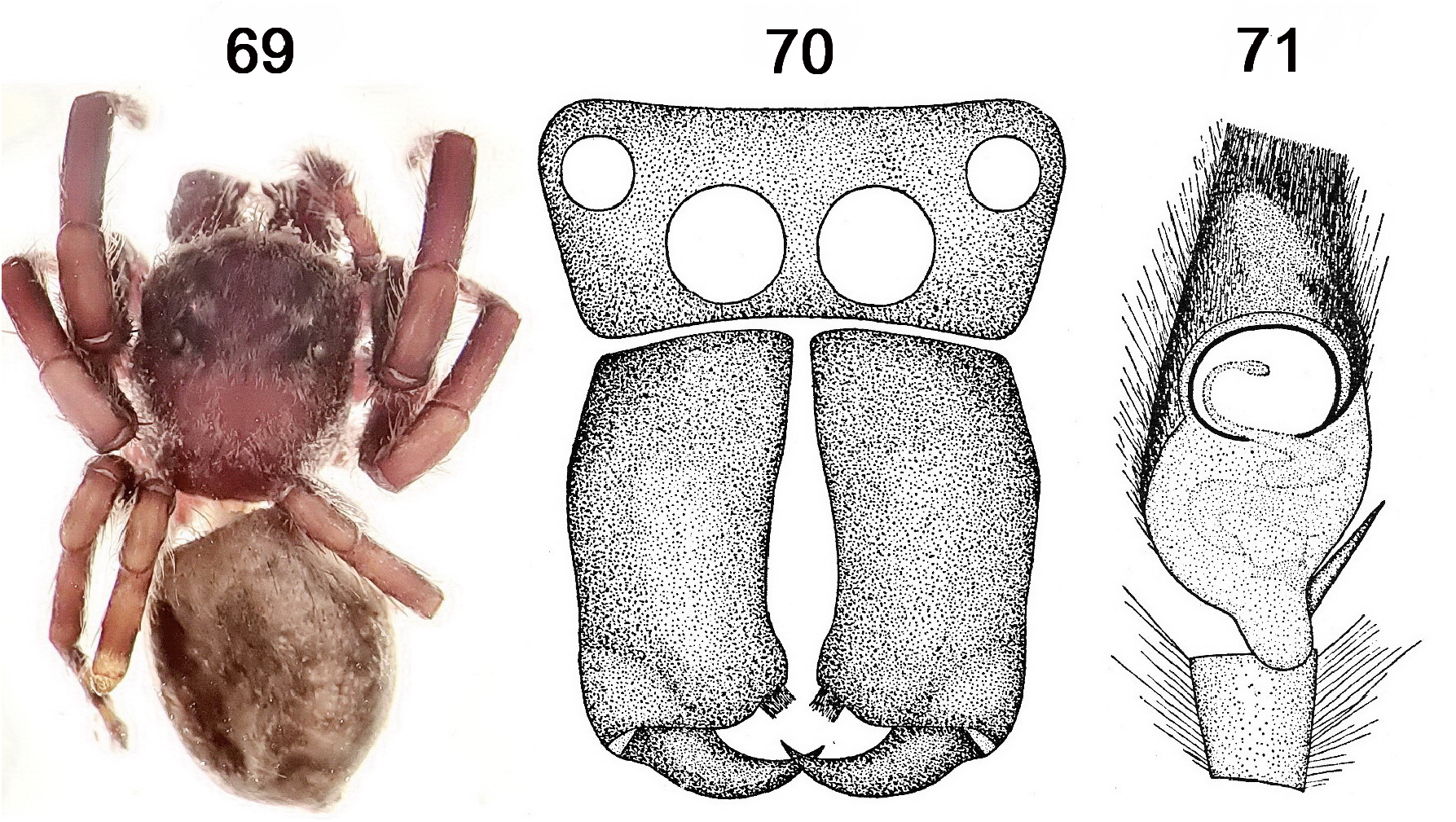

Figs 68–71 View FIGURE 68 View FIGURES 69–71

Plexippus incanus Karsch, 1878: 25 .

Scaea vestita Koch L., 1879: 1142 pl. 94, fig. 4, 5., Peckham & Peckham 1901: 302 pl. 25, fig. 2.

Servaea vestita: Simon, 1888: 283 View in CoL , Prószyński 1984: 131; 1987: 105; Davies & Żabka 1989: 220; Żabka 1991 52; Prószyński, 2017: 76 (removed from synonomy).

Plexippus validus Urquhart, 1893: 127 , Hickman 1967: 84, figs. 147–9, preoccupied. ( Plexippus validus Thorell, 1877 ).

Cytaea morrisoni Dunn, 1951: 16 , figs 8–9 – New synonym.

Servaea incana: Żabka, 1991: 52 View in CoL , Richardson & Gunter 2012: 12 View Cited Treatment , figs 6–22.

Material examined. Holotype of Cytaea morrisoni . M, Ravensthorpe-Ongerup , Western Australia, 118.65°E, 33.95°S, 3 Sept. 1947, R.T.M. Prescott, (MVMA K947). GoogleMaps

Remarks. This genus was revised by Richardson & Gunter (2012). More recently Prószyński (2017) has suggested that S. vestita should be restored from synonomy with S. incana as proposed by Richardson and Gunter (2012). Prószyński’s suggestion was made solely on the basis of slight differences in the shape of the spermathecae in the area surrounding the exit to the fertilization duct in the drawings of two types in Richardson and Gunter (2012, figs 10, 13) and without supporting evidence from other characters or specimens. Examination of cleared epigynes in a range of specimens during the original study showed there was variation in shape between specimens and that intermediate states between those found in the types were present ( Fig. 68 View FIGURE 68 ). Richardson & Gunter (2012) pointed out the lack of any correlation between different character types stating: “ the larger forms … vary in color, the pattern of abdominal markings, size and female genital morphology with no consistent correlation between these characters ”. The radical changes in color patterns could be a response to wasp predation. Inspection of paper wasp nests ( Yuan et al. 2020; Richardson unpublished data) showed that the wasps normally used only a single species in each nest, though a different species could be used in different nests at the same location; presumable the wasps established a search image on the first specimen captured. Radically varying the abdominal color pattern would reduce the risk of capture.

As part of the original work, COI DNA sequences were obtained from a range of differently colored specimens from widely separated locations (following longstanding usage: light specimens ‘ incana ’; dark specimens ‘ vestita ’ as shown for the types in Richardson & Gunter 2012, figs 6, 7). The sequence information was not considered by Prószyński (2017). Specimens of ‘incana’ (n=5) varied by 1–16 nucleotide differences and ‘vestita’ (n=6) by 0–18. The variation between the replicates of ‘incana’ and ‘vestita’ ranged from 0–20 nucleotides with an identical sequence being found for one pair of specimens (a ‘vestita’ from New South Wales and an ‘incana’ from South Australia). Neighbor Joining analysis showed the sequence differences were such that the sequences of specimens of the two forms were interspersed within a single close-knit cluster and well separated from all other species (differences <2% versus>4%). As a consequence, there is no morphological or sequence evidence at present supporting Prószyński’s (2017) suggested rearrangement and evidence to the contrary. Consequently, it is not accepted and the place of S. vestita as a junior synonym of S. incana should be maintained.

In the process of other work, a specimen was discovered that was the holotype of a further name, Cytaea morrisoni Dunn, 1951 , that was already known to be misplaced (M. Żabka in Richardson 2021). The information in Dunn (1951) and a new photograph, showing a dorsal view of the holotype ( Figs 69–71 View FIGURES 69–71 ), clearly place the specimen in the species Servaea incana and the name is here placed in that synonymy. Dunn’s fig. 9 shows that the palp has the standard form found in Servaea while fig. 8 shows the chelicerae expected for S. incana (large relative to the face, strongly geniculate with a distinct shape and with the three promarginal teeth placed on a distinct mound on the median distal corner). The total length of the animal is that expected for S. incana and is much larger than that of other Western Australian species. Servaea incana is well known from many specimens from south-western Australia.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Servaea incana (Karsch, 1878)

| Richardson, Barry J. 2022 |

Servaea vestita

| Proszynski, J. 2017: 76 |

Cytaea morrisoni

| Dunn, R. A. 1951: 16 |