Euhaplorchis californiensis Martin, 1950

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4711.3.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:85D81C2D-0B66-4C0D-B708-AAF1DAD6018B |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5658148 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EF6AD377-895C-8B3D-FF39-FA8FFE54FD12 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Euhaplorchis californiensis Martin |

| status |

|

Euhaplorchis californiensis Martin View in CoL

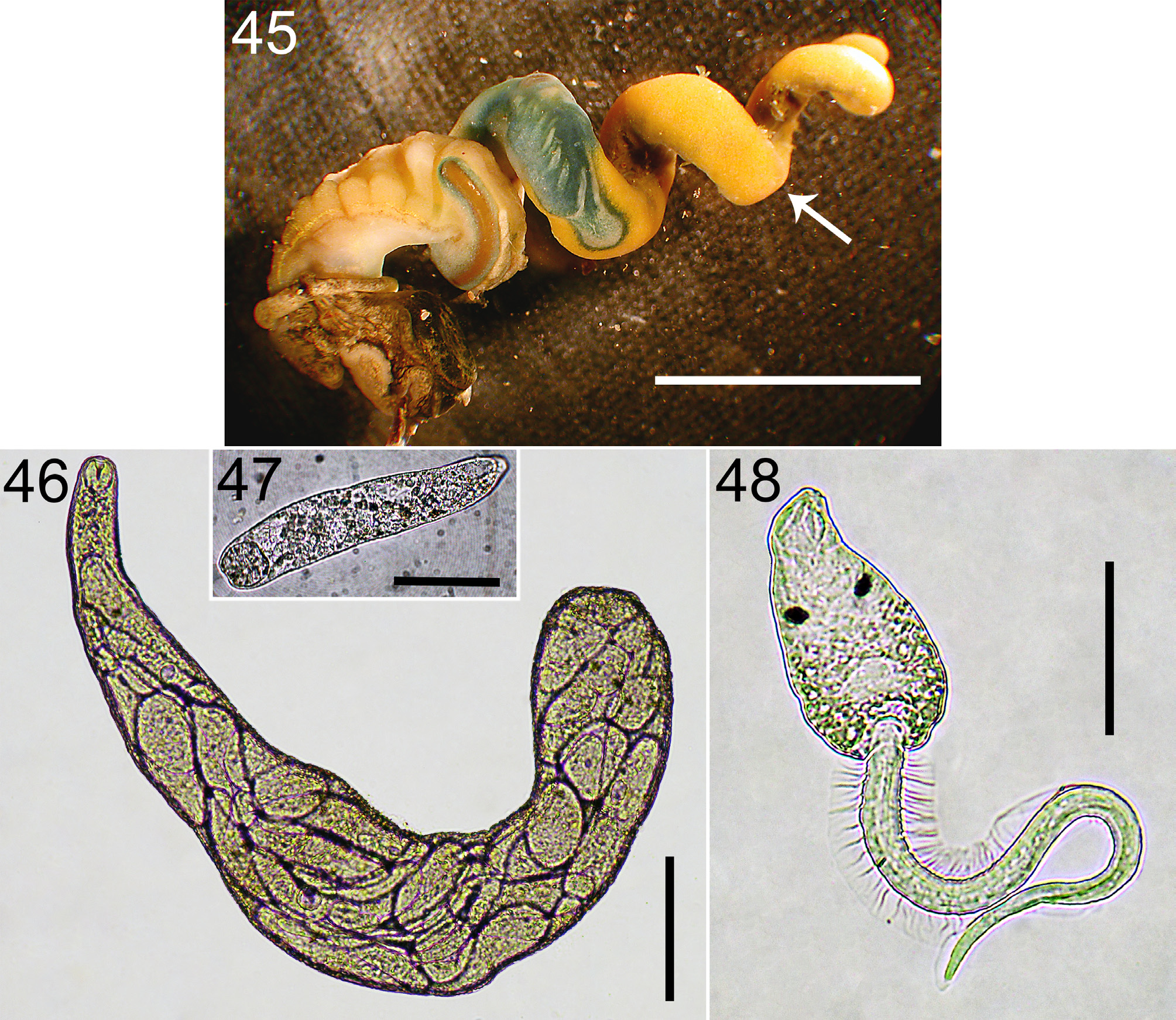

(11. Euca; Figs. 1 View FIGURE 1 , 45–48 View FIGURES 45–48 )

Diagnosis: Parthenitae. Colony comprised of active rediae, densely concentrated in snail gonad region. Rediae translucent white, grey, weak yellow, or colorless; ~ 200–600 µm long, elongate (length:width ~4:1 to 8:1), sausage-shaped.

Cercaria . Body mostly translucent colorless; oculate; with oral sucker and no ventral sucker; with seven pairs of penetration glands, the bodies of which are interspersed from anterio-medial of genital primordium to posterior body wall lateral to excretory bladder; body ~ 150 µm long, much shorter than tail (<1/2 length); tail with dorso-ventral fins (originating in middle third of tail length, extending around tail tip) and lateral fins (originating basally, next to cercaria body, and inserting in middle third of tail length).

Cercaria behavior: Fresh, emerged cercariae remain in water column, swim intermittently in short bursts, with periods of resting and slow sinking.

Similar species: Euca is most reliably and readily distinguished from Acha [10] by the position of the penetration gland bodies, which are readily observable with flattened cercariae at 100x on a compound scope (and even sometimes at the dissection scope). Although Euca does have narrower lateral tail fins than Acha on average, there appears to be overlap; so, tail fin width is not a consistently reliable diagnostic trait. Martin (1972) used the flame-cell grouping to distinguish Acha from Euca, but the flame cells are difficult to see, requiring leaving specimens on a slide for a while and 1000x magnification.

Remarks: Martin (1950a) documented the life cycle and described the species; he described the rediae and cercariae from natural infections, and metacercariae and adults from experimentally infected second intermediate and final hosts. I suspect that cercariae of Euhaplorchis californiensis were accidentally pooled with Acanthotrema hancocki to comprise Maxon & Pequegnat’s (1949) Pleurolophocercous I.

Readers should note that I believe that reports of Euca in California horn snails at Bolinas Lagoon (central California) in some ecological research ( Koprivnikar et al. 2010; Sousa 1993) are a result of misidentification, and that the research actually dealt with A. hancocki (Acha) , which otherwise went unrecognized in those studies. I base this idea mostly on dissections of thousands of snails from Bolinas Lagoon and nearby areas (since early this century) that indicate an almost complete absence of Euca in central California north of Morro Bay, but relatively common Acha (Hechinger et al., unpublished data). We also might expect Euca to be missing from Bolinas because its only known second intermediate host, the California Killifish ( Fundulus parvipinnis Girard ) does not occur that far north. Careful work should examine whether a cryptic species of Acha explains the likely misidentification.

Mature, ripe colonies comprise ~19% the soft-tissue weight of an infected snail (summer-time estimate derived from information in [ Hechinger et al. 2009]).

Unlike many other trematodes in the guild, infection by Euca appears to cause (stolen) snail bodies to grow at the same rate as uninfected (male) snails ( Hechinger 2010).

Euca has a caste of soldier rediae ( Garcia-Vedrenne et al. 2017).

Nadakal (1960a;b) presents information on the pigments of the rediae and cercariae of this species.

As part of one of the first studies documenting the syncytial nature of trematode integuments, Bils and Martin (1966) examined the fine structure and development of the tegument of the rediae and cercariae of this species.

Oates and Fingerut (2011) used histology to carefully document what is readily observed in fresh dissections: that Euca cercaria, like most or all of the trematodes in the guild, make their way to, and accumulate in, the host snail’s perirectal sinus before exiting the host. The authors used videography to document that the cercariae exit snail tissues from an area near the snail’s anus.

Fingerut et al. (2003a) presents information on the relationship between cercaria emergence and temperature for this species.

Cercariae of this species are positively phototactic and negatively geotactic ( Weinersmith et al. 2018).

This species is famous for modifying the behavior of its second intermediate host fish. Infected fishes exhibit 8x more conspicuous behaviors in the laboratory and are 10–30x more likely to be eaten by final host birds ( Lafferty & Morris 1996).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.