Bituminaria basaltica Miniss., C. Brullo, Brullo, Giusso & Sciandr., 2013

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.98.1.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/AE024956-FFD2-1B4C-FF27-72E7FAC1568C |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe (2021-07-05 22:01:09, last updated by Plazi 2023-11-03 06:09:29) |

|

scientific name |

Bituminaria basaltica Miniss., C. Brullo, Brullo, Giusso & Sciandr. |

| status |

sp. nov. |

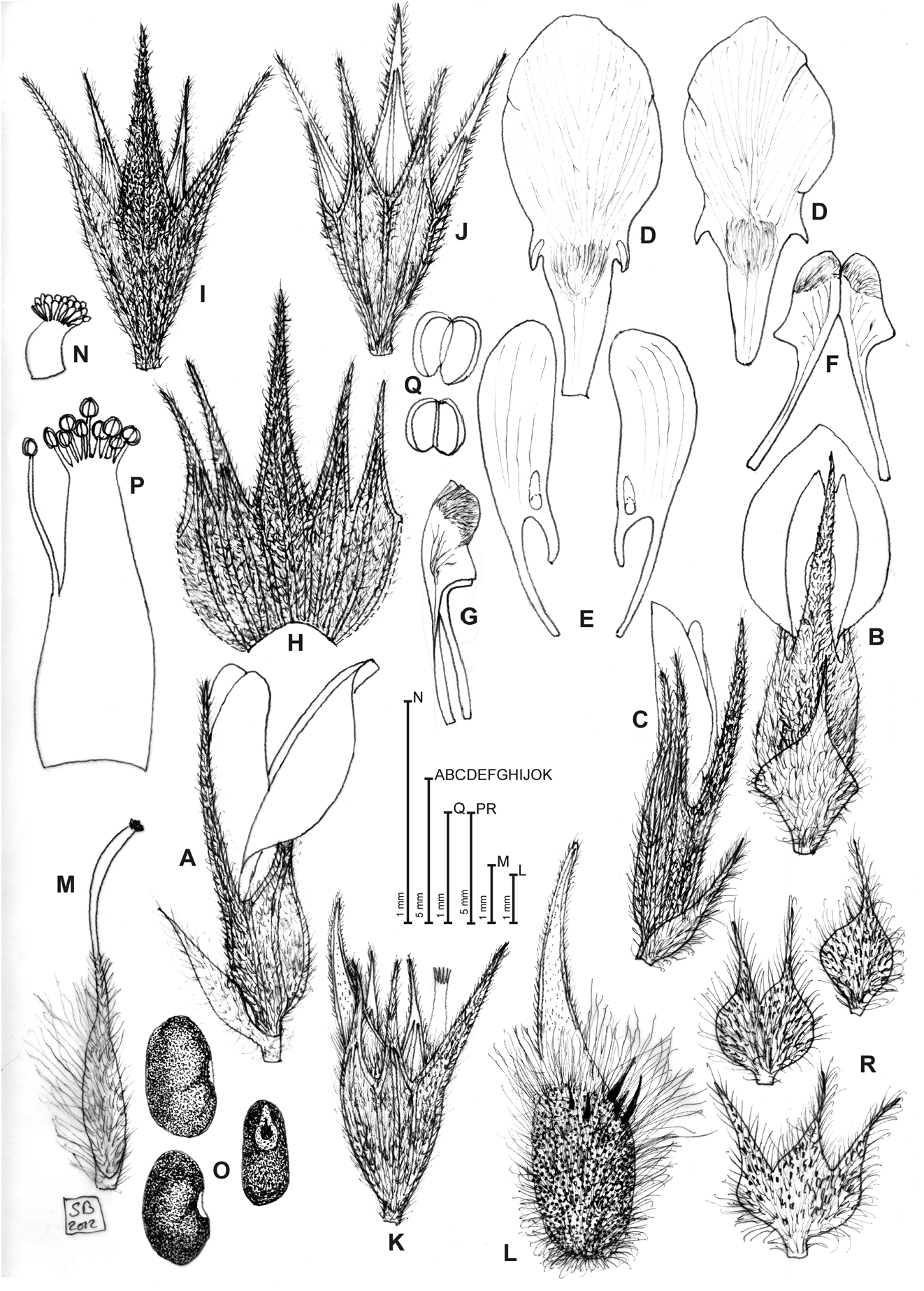

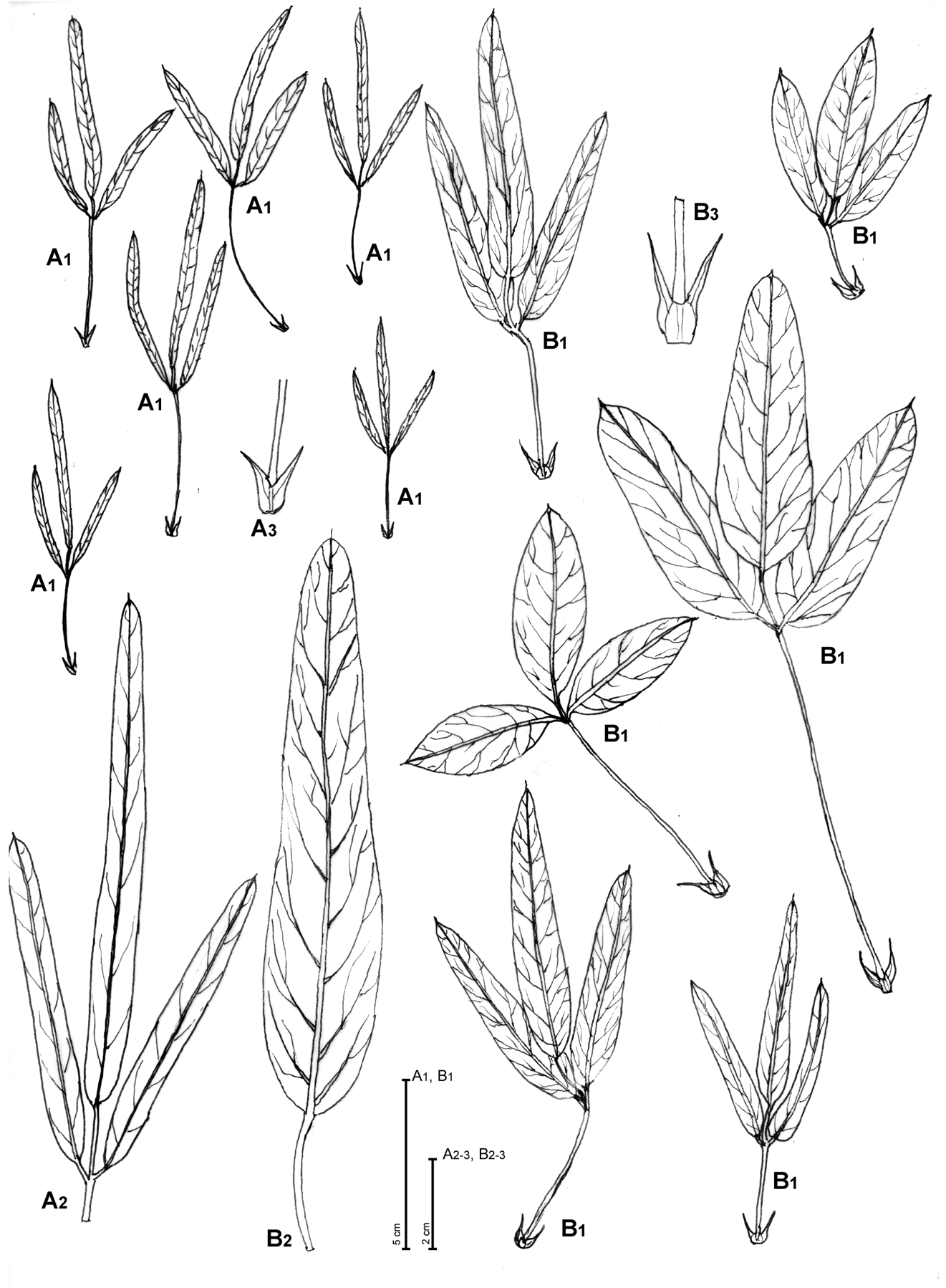

Bituminaria basaltica Miniss., C. Brullo, Brullo, Giusso & Sciandr. View in CoL , sp. nov. ( Figs. 1 View FIGURE 1 , 2A View FIGURE 2 , 3 View FIGURE 3 )

Species Bituminaria bituminosa similis sed foliis brevioribus, linearibus, floribus minoribus, corolla candida, calicem subaequanti vel leviter longiore, stigmate papillato, legumnibus et seminibus brevioribus differt.

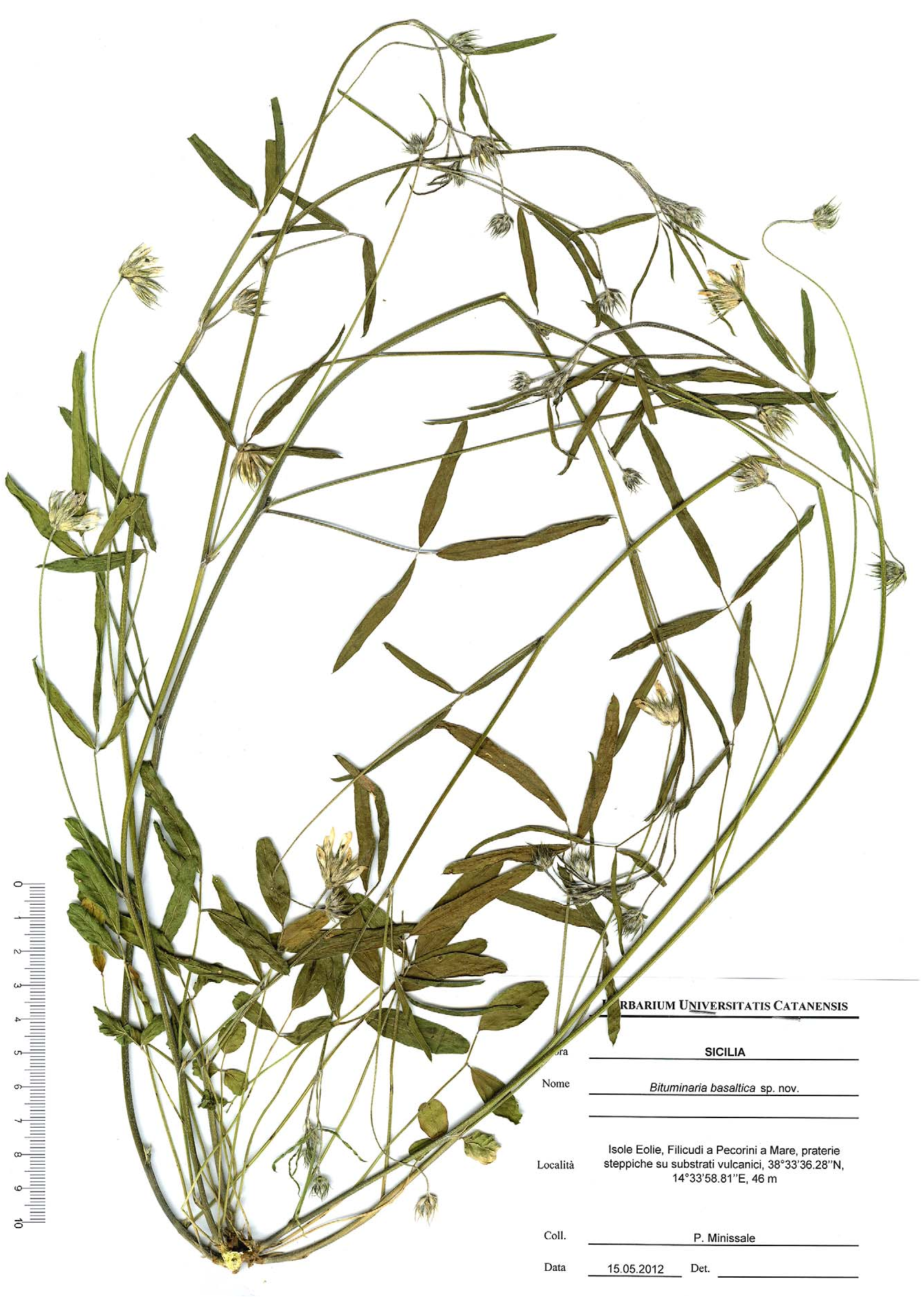

Types: — ITALY. Sicily: Filicudi a Pecorini a Mare , praterie steppiche su substrati vulcanici, 38°33’36.28"N, 14°33’58.81"E, 46 m, 15 May 2012, P GoogleMaps . Minissale s.n. (holotype CAT!, isotypes CAT!, FI!) .

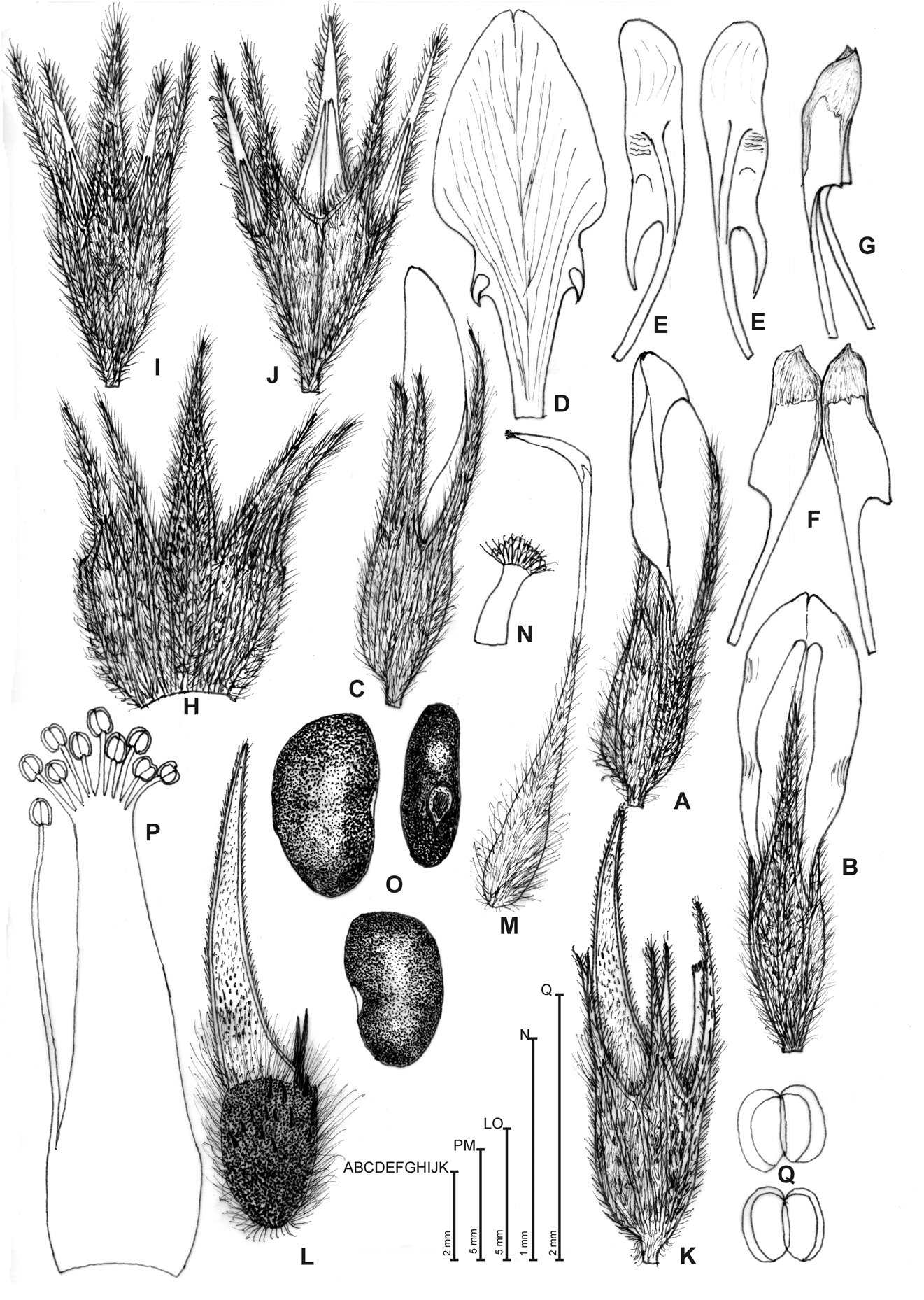

Habit erect or ascending perennial, with numerous rigid and striate woody stems, up to 60 cm tall, green, appressed-hirsute, no smelling of pitch. Basal leaf stipules lanceolate-ensiform, adnate to the petiole, 4–6 mm long. Basal leaves long petiolate, 50–100 mm long; leaves digitately 3-foliate, the central leaflet longer and petiolate, the lateral leaflets shorter and subsessile; leaflets rounded-elliptical to linear-lanceolate, hirsute abaxially and glabrous or subglabrous adaxially, the terminal one 11–40 x 7–15 mm, and petiole 4–12 mm long. the lateral ones 8–38 mm x 5–12 mm and petiole 1–2 mm long. Stipules of cauline 3–5 mm long; cauline leaves smaller than basal ones; petiole 40–50 mm long; leaflets linear, the terminal one 35–55 x 2–6 mm and petiole 6–8 mm long, the lateral ones 25–45 mm x 2–5 mm and petiole 1–2 mm long. Raceme subcapitate, 10–16 mm long, 6–12(–16)–flowered; bracts, upper part of peduncles and calyces, covered with white and black hairs; peduncles 100–160 mm long, longer than the leaf. Bracts 6–8 mm long, 1–3-toothed. Calyx 10–13 mm long, 10-nerved with unequal triangular-subulate teeth; tube 4–5 mm long; lower tooth 6–9 mm long; lateral teeth 4–6 mm long. Corolla 11–13 mm long, subequal to slightly longer than the calyx, purely white; standard spathulate, rounded to obtuse at the apex, 11–13 x 5–6 mm, claw slightly tinged with pale lilac; wings 10–11 mm long, with limb 2.5–3.0 mm wide; keel 7.5–8.5 mm long, with limb 1.5–1.8 mm wide, having a dark violet spot above. Staminal tube 7–8 mm long; anthers 0.5–0.6 mm long. Pistil 6–7 mm long, hairy on the ovary and lower part of the style; stigma with numerous papillae. Pod indehiscent, included in the calyx, 9–10 mm long (beak included), with corpus densely covered by setaceous hairs, 0.5–2.0 mm long, mixed to some rigid black prickles; beak flat, falcate, 5.5–6 mm long, glabrous, ciliate only at the margin. Seed adherent to pericarp, laterally compressed, subreniform, 3.5–4 x 2–2.2 mm, blackish-brown.

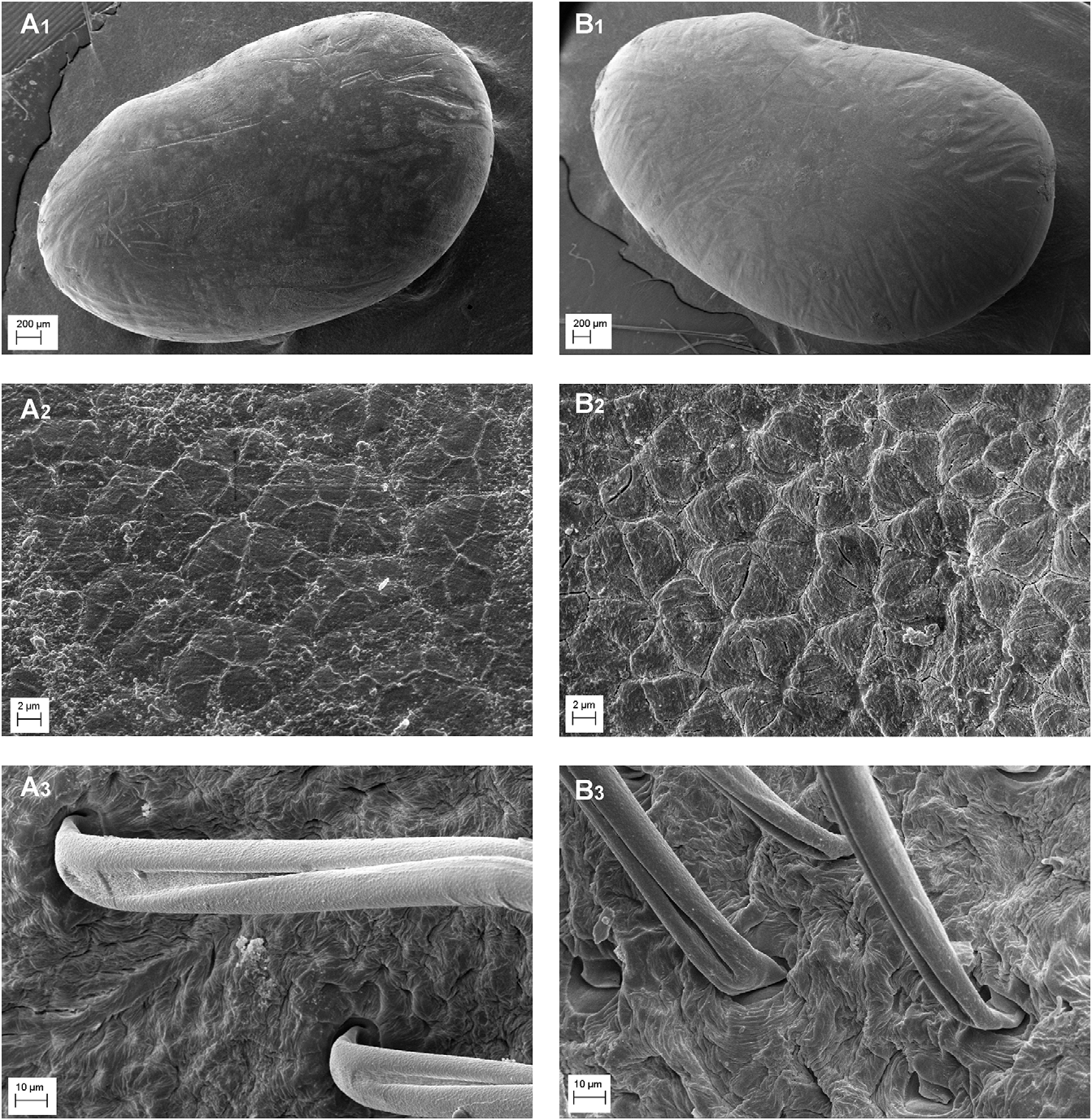

Seed and pod micro-morphology:— As suggested by literature, the exomorphic features of seed testa, based on scanning electron microscopy (SEM), can be used as an additional character for the identification of a given taxon ( Barthlott 1981, Koul et al. 2000, Fitsch et al. 2006, Kasem et al. 2011, Celep et al. 2012). Several studies on the seed coat micro-morphology of the legume taxa were performed by various authors ( Murthy and Sanjappa 2002, Kirkbride et al. 2003, Salimpour et al. 2007, Al-Ghamdi et al. 2010, Bacchetta & Brullo 2010, Fawzel 2011, Gandhi et al. 2011, Brullo et al. 2011a, Brullo et al. 2013), who used several characters to resolve systematic problems. In fact, seed sculptures are usually considered as a conservative and stable character, having relevant taxonomical and phylogenetic implications.

The seed coat of B. basaltica shows a fine and undulate reticulum bounding the single cells, which are irregularly polygonal and 2–5 µm wide. The anticlinal walls are raised, with minutely rugose-undulate tops, while the periclinal walls are flat with epidermis finely reticulate-rugose ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 , A 1–2 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 ). In order to elucidate the relationships with the allied B. bituminosa , its seed testa was also examined. Actually, the seeds of B. bituminosa are well differentiated from the new species in having, apart from the size (give the measurements), coat with a reticulum always more or less irregualar, with bigger cells, 5–9 µm wide, bounding by straight to curved furrows. The anticlinal walls are incised-depressed, while the periclinal walls are weakly convex, with epidermis uniformly sulcate by curved and concentric grooves ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 , B 1–2 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 ).

Other significant differences can be observed in the pod indumentum. In particular, B. basaltica has hairs basally that are 22–27 µm wide and a longitudinal furrow broadly widened at the hair base ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 , A 3 View FIGURE 3 ), while in B. bituminosa hairs are 12–17 µm wide at the base and the longitudinal furrow is uniformly narrowed ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 , B 3 View FIGURE 3 ).

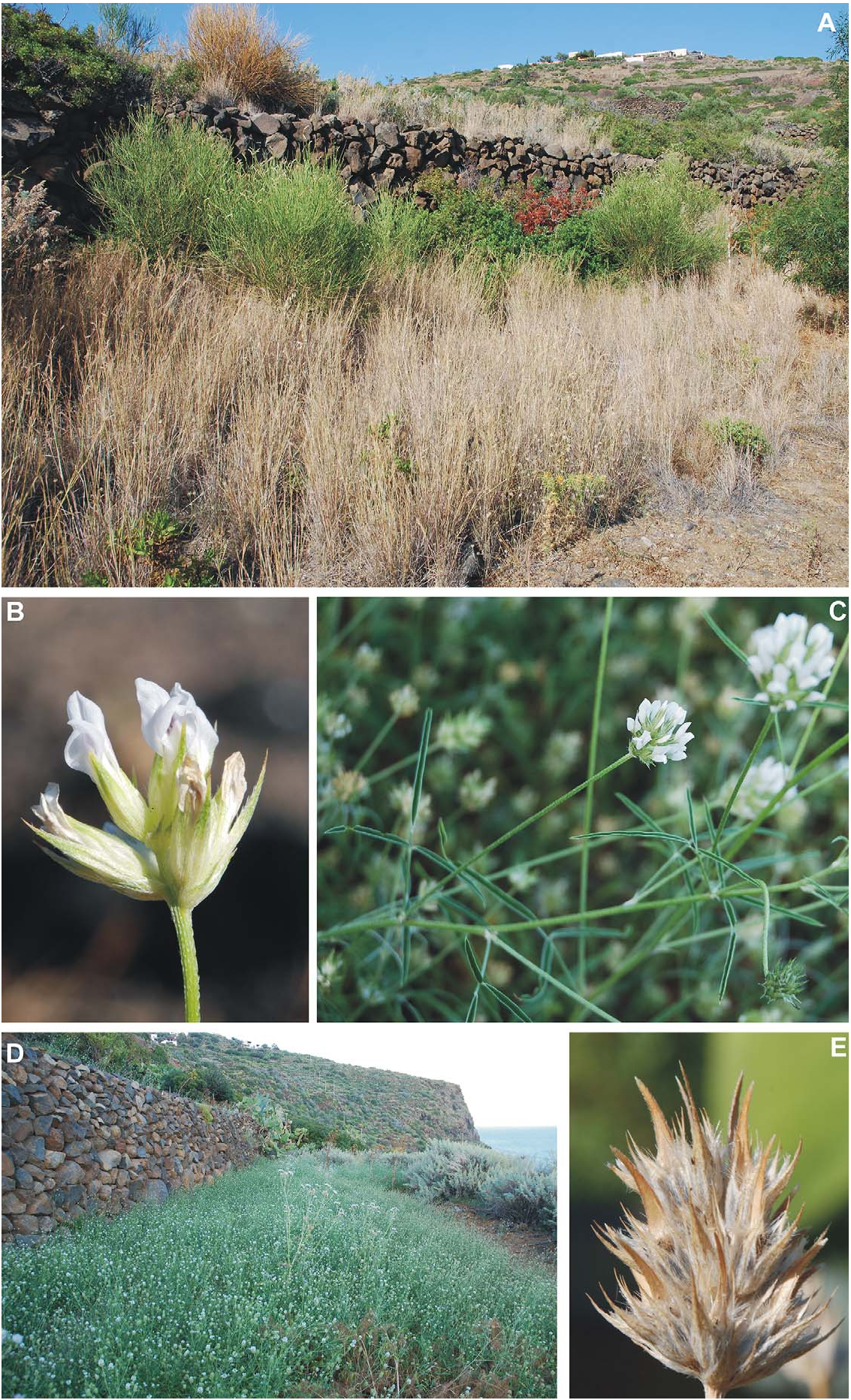

Habitat: — Bituminaria basaltica grows on volcanic soils, at an elevation of 20– 100 m. The plant is mainly localized on dry grasslands dominated by Hyparrhenia hirta , abandoned fields and roadsides ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ) where hemichryptophytes are also abundant. From the bioclimatic viewpoint (Rivas-Martinez 2004), Filicudi falls within the Mediterranean Pluviseasonal Oceanic bioclimate, and the growing sites of B. basaltica are always south-facing with mean annual precipitations of ca. 500 mm and mean annual temperatures of 18°C (thermomediterranean upper dry bioclimatic belt).

Distribution: — Based on many field investigations carried out in the Aeolian Archipelago, B. basaltica seems to be endemic of Filicudi. No other Bituminaria species has been recorded from the other islands of this archipelago ( Lojacono-Pojero 1878, Ferro & Furnari 1968a, 1968b, 1970, Di Benedetto 1973).

Etymology: —The specific epithet refers to the bedrock of the dwelled sites, which is represented by basaltic rocks.

Phenology: —Flowering April to early June, fruiting June to August.

Conservation status: —According to De Rosa et al. (2003), the age of the oldest exposed lavas on Filicudi is about 219 ka. Filicudi with an area of 9.5 km 2 is the fifth-largest of the seven islets of the Aeolian Archipelago, which is located ca. 45 km off NE Sicily. The highest point is Monte Fossa delle Felci at 774 m of elevation. The long-lasting human exploitation, whose occurrence is dated back to the Neolithic, about 6000 years ago ( Bernabò Brea & Cavalier 1991) has heavily altered the natural vegetation. Both husbandry and coppicing led to the almost complete disappearance of woodlands suddenly replaced by crops, shrubby vegetation, dry grasslands, and abandoned fields. Therefore, the current spread of B. basaltica on the island has been likely favoured by the human disturbance, being a species rather linked to disturbed and ruderal habitats. Considering that the new species is circumscribed to a small island and that grazing and fires may significantly reduce the number of individuals, it is suggested to add B. basaltica to the Italian Red List as Vulnerable (VU). In particular, based on the IUCN criteria ( IUCN 2010), we propose to include this species in the following category: VU B2, C.

Taxonomic remarks: —According to Stirton (1981a), two morphologically well-differentiated subgenera can be recognized within the genus Bituminaria : subgen. Bituminaria , typified by B. bituminosa , and subgen. Christevenia Barneby ex Stirton (1981a: 318) typified by B. acaulis . The first-mentioned subgenus is caulescent plants with entire leaflets, racemes with axillary peduncles, bracts fused in a toothed blade, calyces ebracteolate and pods with some glabrous spinulose processes, while the last-mentioned subgenus includes acaulescent plants with denticulate leaflets, racemes with scapiform peduncles, two bracts filiform separate to the base calyces provided at the base of a linear bracteole on each side and pods with soft pubescent processes. The morphological features of B. basaltica suggest to include it into the subgen. Bituminaria , together with B. bituminosa , B. morisiana (Pignatti & Metlesics) Greuter (1986: 108) and B. flaccida (Náb.) Greuter (1986: 108) . Morphologically, B. basaltica differs from the other species of this subgenus for shape of cauline leaves, size of of raceme, flower pieces, corolla colour, pods and seeds (see Table 1).

Bituminaria basaltica shows some relationship with B. bituminosa in the habit and ecological characters but it is well differentiated in several characters chiefly regarding size and shape of the leaves, inflorescences, flowers, pods, seeds and corolla colour. In fact, B. bituminosa has elliptic to lanceolate cauline leaflets, 6–22 mm wide, racemes 2–2.8 cm long, with 15–30 flowers, calyx 14–18 mm long, with teeth 7–12 mm long, corolla blue-violet, 15–20 mm long, longer than calyx, with apex emarginate, staminal tube 10–20 mm long, pistil 9–12 mm long, pods (beak included) 13–26 mm long, beak pubescent in the face, seeds 5–7 mm long ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 ). Moreover, B. basaltica is similar to B. flaccida , by having very short pods (max. 10 mm), which occurs in Israel, Jordan and Sinai, but several morphological features and ecological requirements allows distinguishing the two species. Actually, B. flaccida is a typical chasmophyte, having leaflets completely hirsute, the basal ones suborbicular to obovate, 4–15 mm long, the cauline ones obovate to linear-lanceolate 8–20 mm long, racemes 17–20 mm long, 5–8-flowered, with peduncles 2–9 mm long, calyx 9–11 mm long, corolla pink, 16–18 mm long, longer than calyx, staminal tube 11–12 mm long, and pod beak 5 mm long, completely Pubescent. Lastly, even B. morisiana is markedly different from B. basaltica , mainly for the chamaephytic habit, wider leaves, bigger and many-flowered racemes, bigger floral pieces, corolla whiteviolet, pods (beak included) 18–26 mm long, and seeds 5–6 mm long.

Based on the current knowledge, B. basaltica seems to be circumscribed to Filicudi, where it is morphologically stable, showing no variability in the wild.

It is worthy to mention that the Aeolian Archipelago hosts several narrow endemics or rare species, such as Cytisus aeolicus Gussone (1834: 221) , Silene hicesiae Brullo & Signorello (1984: 141) , Centaurea aeolica Gussone ex Candolle (1838: 584) , Genista tyrrhena Valsecchi (1986:145) , Erysimum brulloi Ferro (2009: 298) , Eokochia saxicola ( Gussone 1855: 275) Freitag & G. Kadereit in Kadereit & Freitag (2011: 72), Dianthus rupicola Biv. subsp. aeolicus ( Lojacono-Pojero 1888: 163) Brullo & Minissale (2002: 539) , and Limonium minutiflorum (Guss.) Kuntze (1891: 395) . Therefore, it is possible to consider this archipelago as a micro-hotspot, characterized by very active speciation processes, which is likely a consequence of manifold constraining factors, such as harsh environmental conditions, geological history, and geographical isolation. As in the case of Eokochia saxicola , Cytisus aeolicus and Silene hicesiae , the Aeolian Archipelago probably acted as a refuge area for otherwise extinct species ( Brullo & Signorello 1984, Conte et al. 1998, Cristofolini & Conte 2002, Kadereit & Freitag 2011, Santangelo et al. 2012). The last recorded endemics confirm the peculiarity of the Mediterranean flora, not only for the high rate of narrow endemics particularly on islands or wherever mountains exceed 1500 m in altitude (cf. Pignatti et al. 1980, Greuter 1991, Médail & Quézel 1997, Thompson 2005, Guarino et al. 2005, Brullo et al. 2001, 2005, Brullo et al. 2011b) but also for the peculiar distribution patterns that make the Mediterranean island biogeography so interesting and intriguing ( Troia et al. 2012).

Finally, B. basaltica could also be an interesting species to study for its potential use as a pasture grass and forage plant, similarly to B. bituminosa which has increased in agronomical appeal during the last decade ( Méndez & Fernández 1990, Gutman et al. 2000, Sternberg et al. 2006, Walker et al. 2006, Real et al. 2009, Ventura et al. 2004, Gulumser et al. 2010, Finlayson et al. 2012). The use of B. bituminosa as forage species is well known in the Canary Islands for a long time ( Méndez 2000), where it is not cultivated but spontaneously grazed by livestock or, more frequently, collected and offered to the livestock as hay, thus removing its typical smell of bitumen which causes the refusal by animals when it is still green. In particular, B. bituminosa var. albomarginata , which occurs exclusively in Lanzarote (Canary Islands), was introduced to Australia in 2005 ( Finlayson et al. 2012), in order to experimentally evaluate it for potential release as a commercial forage crop. Its extreme drought tolerance, lower invasiveness together with its ability to produce relatively high quality feed throughout the year, is extremely interesting ( Ventura et al. 2009). Therefore, the potential use of B. basaltica as pasture grass or fodder should be worthy to be tested. In particular, its weak bitumen smell would suggest this legume as fairly good for grazing, and not being a strong colonizer, the risks of becoming a weed are rather low. This potential plant for animal husbandry confirms once more the importance and usefulness of any survey focused on biodiversity, even in areas very explored as the Mediterranean islands.

Al-Ghamdi, F. A. & Al-Zahrani, R. M. (2010) Seed morphology of some species of Tephrosia Pers. (Fabaceae) from Saudi Arabia. Identification of species and systematic significance. Feddes Repertorium 121: 59 - 65. http: // dx. doi. org / 10.1002 / fedr. 201011128

Bacchetta, G. & Brullo, S. (2010) Astragalus tegulensis Bacch. & Brullo (Fabaceae), a new species from Sardinia. Candollea 65: 5 - 14.

Barthlott, W. (1981) Epidermal and seed surface character of plants: Systematic applicability and some evolutionary aspects. Nordic Journal of Botany 1: 345 - 355. http: // dx. doi. org / 10.1111 / j. 1756 - 1051.1981. tb 00704. x

Bernabo Brea, L. & Cavalier, M. (1991) Meligunis Lipara. VI. Filicudi. Insediamenti dell'eta del bronzo. Accademia di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti di Palermo, Palermo, 354 pp.

Brullo, S. & Signorello, P. (1984) Silene hicesiae, a new species from the Aeolian Islands. Willdenowia 14: 141 - 144.

Brullo, S., Giusso del Galdo, G. & Guarino, R. (2001) The orophilous communities of Pino-Juniperetea class in Central and Eastern Mediterranean area. Feddes Repertorium 112: 261 - 308.

Brullo, S. & Minissale, P. (2002) Il gruppo di Dianthus rupicola Biv. nel Mediterraneo centrale. Informatore Botanico Italiano 33: 537 - 542.

Brullo, C., Brullo, S., Giusso del Galdo, G., Minissale, P. & Sciandrello, S. (2011 a) Astragalus raphaelis (Fabaceae), a critical species from Sicily and taxonomic remarks on A. sect. Sesamei. Nordic Journal of Botany 29: 518 - 533.

Brullo, C., Minissale, P., Sciandrello, S. & Spampinato, G. (2011 b) Phytogeographic survey on the endemic vascular flora of the Hyblaean territory (SE Sicily, Italy). Acta Botanica Gallica, 158: 617 - 631.

Brullo, C., Brullo, S., Giusso del Galdo, G., Minissale, P. & Sciandrello, S. (2013) Astragalus kamarinensis (Fabaceae), a new species from Sicily. Annales Botanici Fennici 50: 61 - 67.

Candolle de, A. P. (1838) Prodromus Systematis Naturalis Regni Vegetabilis 6. Treuttel & Wurtz, Parisiis, 687 pp.

Celep, F., Koyuncu, M., Fritsch, R. M., Kahraman, A. & Dogan, M. (2012) Taxonomic importance of Seed Morphology in Allium (Amaryllidaceae). Systematic Botany 37: 893 - 912.

Conte, L., Troia A. & Cristofolini, G. (1998) Genetic diversity in Cytisus aeolicus Guss. (Leguminosae), a rare endemite of the Italian flora. Plant Biosystems 132: 239 - 249

Cristofolini, G. & Conte, L. (2002) Phylogenetic patterns and endemism genesis in Cytisus Desf. (Leguminosae- Cytiseae) and related genera. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences 50 Supplement: 37 - 50.

De Rosa, R., Guillou, H., Mazzuoli, R. & Ventura, G. (2003) New unspiked K-Ar ages of volcanic rocks of the central and western sector of the Aeolian Islands: Reconstruction of the volcanic stages. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 120: 161 - 178.

Di Benedetto, L. (1973) Flora di Alicudi (Isole Eolie). Archivio Botanico e Biogeografico Italiano 49: 1 - 28.

Fawzel, N. M. (2011) Macro-and micromorphological seed characteristics of some selected species of Caesalpinoideae- Leguminosae. Research Journal of Botany 6: 68 - 77.

Ferro, G. & Furnari, F. (1968 a) Flora e vegetazione di Stromboli (Isole Eolie). Archivio Botanico e Biogeografico Italiano 44: 21 - 45.

Ferro, G. & Furnari, F. (1968 b) Flora e vegetazione di Stromboli (Isole Eolie). Archivio Botanico e Biogeografico Italiano 44: 59 - 85.

Ferro, G. & Furnari F. (1970) Flora e vegetazione di Vulcano (Isole Eolie). La Nuova Grafica C. Napoli, Caltagirone, 66 pp.

Ferro, G. (2009) Erysimum brulloi (Brassicaceae), a new species from the Aeolian Archipelago (Sicily). Flora Mediterranea 19: 297 - 302.

Finlayson, J., Reala, D., Nordbloma, T., Revella, C., Ewinga, M. & Kingwellb, R. (2012) Farm level assessment of a novel drought tolerant forage: Tedera (Bituminaria bituminosa C. H. Stirt. var. albomarginata). Agricultural Systems 112: 38 - 47. http: // dx. doi. org / 10.1016 / j. agsy. 2012.06.001

Fitsch, R. M., Kruse, J., Adler, K. & Rutten, T. (2006) Testa sculptures in Allium L. subgen. Melanocrommyum (Webb & Berth.) Rouy (Alliaceae). Feddes Repertorium 117: 250 - 263. http: // dx. doi. org / 10.1002 / fedr. 200611094

Gandhi, D., Albert, S. & Pandya N. (2011) Morphological and micromorphological characterization of some legume seeds from Gujarat, India. Environmental and Experimental Biology 9: 105 - 133.

Greuter, W. (1986) Bituminaria. In: Greuter, W. & Raus, T. (ed.) Med-Checklist Notulae 13. Willdenowia 16: 103 - 116.

Greuter, W. (1991) Botanical diversity, endemism, rarity, and extinction in the Mediterranean area: an analysis based on the published volumes of Med-Checklist. Botanika Chronika 10: 63 - 79.

Gulumser, E. ,, Basaran, U., Acar, Z., Ayan, I. & Mut, H. (2010) Determination of some agronomic traits of Bituminaria bituminosa accessions collected from Middle Black Sea Region. Option Mediterraneennes, A 92: 105 - 108.

Gussone G. (1855) Enumeratio plantarum vascularium in Insula Inarime sponte provenientium vel oeconomico usu passim cultarum. Ex Vanni typographeo, Neapoli, 428 pp.

Gussone, G. (1834) Florae Siculae Prodromus Supplement 2. Regia Typographia, Neapoli, 72 pp.

Gutman, M., Perevolotsky, A. & Sternberg, M. (2000) Grazing effects on a perennial legume, Bituminaria bituminosa (L.) Stirton, in a Mediterranean rangeland. Cahiers Options Mediterraneennes 45: 299 - 303.

IUCN (2010) The IUCN red list of threatened species, version 2010.4. IUCN Red List Unit, Cambridge, U. K. Available from: http: // www. iucnredlist. org / (accessed: 20 January 2012).

Kadereit, G. & Freitag, H. (2011) Molecular phylogeny of Camphorosmeae (Camphorosmoideae, Chenopodiaceae): Implications for biogeography, evolution of C 4 - photosynthesis and taxonomy. Taxon 60: 51 - 78.

Kasem, W. T., Ghareeb, A. & Marwa, E. (2011) Seed morphology and seed coat sculpturing of 32 taxa of Family Brassicaceae. Journal of American Science 7: 166 - 178.

Kirkbride, J. H. Jr., Gunn, C. R. & Weitzman, A. L. (2003) Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae), vol. 1 - 2. Technical Bulletin 1890: 1 - 1185.

Koul, K. K., Nagpal, R. & Raina, S. N. (2000) Seed coat microsculpturing in Brassica and allied genera (Subtribe Brassicinae, Raphaninae, Moricandinae). Annals of Botany 86: 385 - 397.

Kuntze, C. E. O. (1891) Revisio Generum Plantarum 2. Universitasdruckerei von H. Sturtz, Wurzburg, 1011 pp.

Lojacono-Pojero, M. (1878) Le isole Eolie e la loro vegetazione con enumerazione delle piante spontanee vascolari. Stamperia di Giovanni Lorsnaider, Palermo, 140 pp.

Lojacono-Pojero, M. (1888) Flora sicula, o Descrizione delle Piante vascolari spontanee o indigenate in Sicilia 1. Tipografia Virzi, Palermo, 234 pp.

Medail, F. & Quezel, P. (1997) Hot-spots analysis for conservation of plant biodiversity in the Mediterranean Basin. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 84: 112 - 127. http: // dx. doi. org / 10.2307 / 2399957

Mendez, P. & Fernandez, M. (1990) Interes forrajero de las variedades de Bituminaria bituminosa (L.) Stirton ( tedera ) de Canarias. XXX Reunion Cientifica de la Sociedad Espanola para el Estudio de los Pastos, Donostia-San Sabastian (Spain): 264 - 272.

Mendez, P. (2000) El heno de tedera (Bituminaria bituminosa): Un forraje apetecible para el caprino. 3 Reunion Iberica de Pastos y Forrajes, Galicia (Spain): 412 - 414.

Murthy, G. V. S. & Sanjappa, M. (2002) SEM studies on seed morphology of Indigofera L. (Fabaceae) and its taxonomic utility. Rheedea 12: 21 - 51.

Pignatti, E., Pignatti, S., Nimis, P. L. & Avanzini, A. (1980) La vegetazione ad arbusti spinosi emisferici: Contributo alla interpretazione delle fasce di vegetazione delle alte montagne dell' Italia mediterranea. Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Roma AQ / 1 / 79: 1 - 130.

Real, D., Correal, E., Mendez, P., Santos, A., Rios, S. Sternberg, Z. M., Dini-Papanastasi, O., Pecetti, L. & Tava, A. (2009) Bituminaria bituminosa CH Stirton. In: Grassland Species Profiles. FAO, Roma. http: // www. fao. org / ag / AGP / AGPC / doc / GBASE / new _ species / tedera / bitbit. htm. (Accessed 28 September 2012).

Salimpour, F., Mostafavi, G. & Sharifnia, F. (2007) Micromorphologic study of the seed of the genus Trifolium, section Lotoidea, in Iran. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 10: 378 - 382. http: // dx. doi. org / 10.3923 / pjbs. 2007.378.382

Santangelo, A., Croce, A., Lo Cascio, P., Pasta, S., Strumia, S. & Troia, A. (2012) Eokochia saxicola (Guss.) Freitag et G. Kadereit. Informatore Botanico Italiano. 44: 428 - 431.

Sternberg, M., Gishi, N. & Mabjeesh, S. J. (2006) Effects of grazing on Bituminaria bituminosa (L) Stirton: A potential forage crop in Mediterranean grasslands. Journal of Agronomy & Crop Science 192: 399 - 407. http: // dx. doi. org / 10.1111 / j. 1439 - 037 X. 2006.00227. x

Stirton, C. H. (1981 a) Studies in the Leguminosae-Papilionoideae of southern Africa. Bothalia 13: 317 - 325.

Thompson, J. D. (2005) Plant evolution in the Mediterranean. Oxford University Press, New York, 293 pp.

Troia, A., Raimondo, F. M. & Mazzola, P. (2012) Mediterranean island biogeography: Analysis of fern species distribution in the system of islets around Sicily. Plant Biosystems 146: 576 - 585.

Valsecchi, F. (1986) Due nuove specie del genere Genista L. nel Mediterraneo. Bollettino della Societa Sarda di Scienze Naturali 25: 143 - 147.

Ventura, M. R., Castanon, J. I. R., Pieltain, M. C. & Flores, M. P. (2004) Native value of forage shrubs: Bituminaria bituminosa, Rumex lunaria, Acacia salicina, Cassia sturtii and Adenocorpus foliosus. Small Ruminant Research 52: 13 - 18. http: // dx. doi. org / 10.1016 / S 0921 - 4488 (03) 00225 - 6

Ventura, M. R., Castanon, J. I. R. & Mendez, P. (2009) Effect of season on tedera (Bituminaria bituminosa) intake by goats. Animal Feed Science and Technology 153: 314 - 319. http: // dx. doi. org / 10.1016 / j. anifeedsci. 2009.06.018

Walker, D. J, Monino, I. & Correal, E. (2006) Genome size in Bituminaria bituminosa (L.) C. H. Stirton (Fabaceae) populations: Separation of true differences from environmental effects on DNA determination Environmental and Experimental Botany 55: 258 - 265. http: // dx. doi. org / 10.1016 / j. envexpbot. 2004.11.005

FIGURE 1. Diagnostic features of Bituminaria basaltica. A. Flower (lateral view). B. Flower (ventral view). C. Bud. D. Standards. E. Wings. F.Keel (open). G.Keel (lateral view). H. Calyx (open). I. Calyx (ventral view). J. Calyx (dorsal view). K. Calyx and immature pod. L. Calyx and mature pod. M. Pistil. N. Stigma. O. Seeds. P. Staminal tube. Q. Anthers. R. Bracts. Illustration by Salvatore Brullo based on Minissale s.n. (CAT).

FIGURE 2. Variability in leaf and stipule shape of Bituminaria basaltica (A1–3) and B. bituminosa (B1–3). Illustration by Salvatore Brullo based on Minissale s.n. (CAT) for A and “Catania” Brullo s.n. (CAT) for B.

FIGURE 4. SEM micrographs of the seed coats of Bituminaria basaltica (A1–2) and B. bituminosa (B1–2) at low magnification (A1 x 20 and B1 x 28) and at high magnification (A2 and B2 x 2500) and hairs on the pods of B. basaltica (A3) and B. bituminosa (B3) at medium magnification (x 700), from material of Filicudi, Minissale s.n. (CAT) and Catania Brullo s.n. (CAT).

FIGURE 5. Phenological features of Bituminaria basaltica. A. Natural stands with Hyparrhenia hirta dry grassland habitat (Filicudi). B. Inflorescence. C. Terminal branches with leaves and inflorescences. D. Synanthropic stands abandoned fields (Filicudi). E. Fructified inflorescence. (Photos by P. Minissale).

FIGURE 6. Diagnostic features of Bituminaria bituminosa. A. Flower (lateral view). B. Flower (ventral view). C. Bud. D. Standard. E. Wings. F. Keel (open). G. Keel (lateral view). H. Calyx (open). I. Calyx (ventral view). J. Calyx (dorsal view). K. Fruiting calyx and pod. L. Pod. M. Pistil. N. Stigma. O. Seeds. P.Staminal tube. Q. Anthers. R. Illustration by Salvatore Brullo based on specimens from Catania, Brullo s.n. (CAT).

| P |

Museum National d' Histoire Naturelle, Paris (MNHN) - Vascular Plants |

| CAT |

Università di Catania |

| FI |

Natural History Museum |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |