Bertorsonidra Rosso, 2010

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5252/z2010n3a7 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D6E535-4F14-2823-FF7E-F996FDAB3BB7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Bertorsonidra Rosso |

| status |

gen. nov. |

Genus Bertorsonidra Rosso , n. gen.

DIAGNOSIS. — Colony encrusting attached to the substratum through pillar-like structures emanating from the basal surface. Autozooids loosely arranged and leaving interzooidal spaces. Frontal wall pseudoporous bordered by marginal pores. Orifice semicircular with a proximal sinus and lateral condyles. Peristome inconspicuous. Spines present, not articulated at the base, two persisting in ovicellate zooids. Suboral umbo sporadic but characteristic. Avicularia present, typically single, lateral-suboral on an inflated cystid. Ovicell prominent with uncalcified ectooecium and a granular, evenly pseudoporous entooecium. Interzooidal communication through uniporous septulae arranged in a band in the vertical walls.

TYPE SPECIES. — Tremopora prenanti Gautier, 1955 by present designation.

ETYMOLOGY. — Th e name is an anagram of Robertsonidra , a closely related genus.

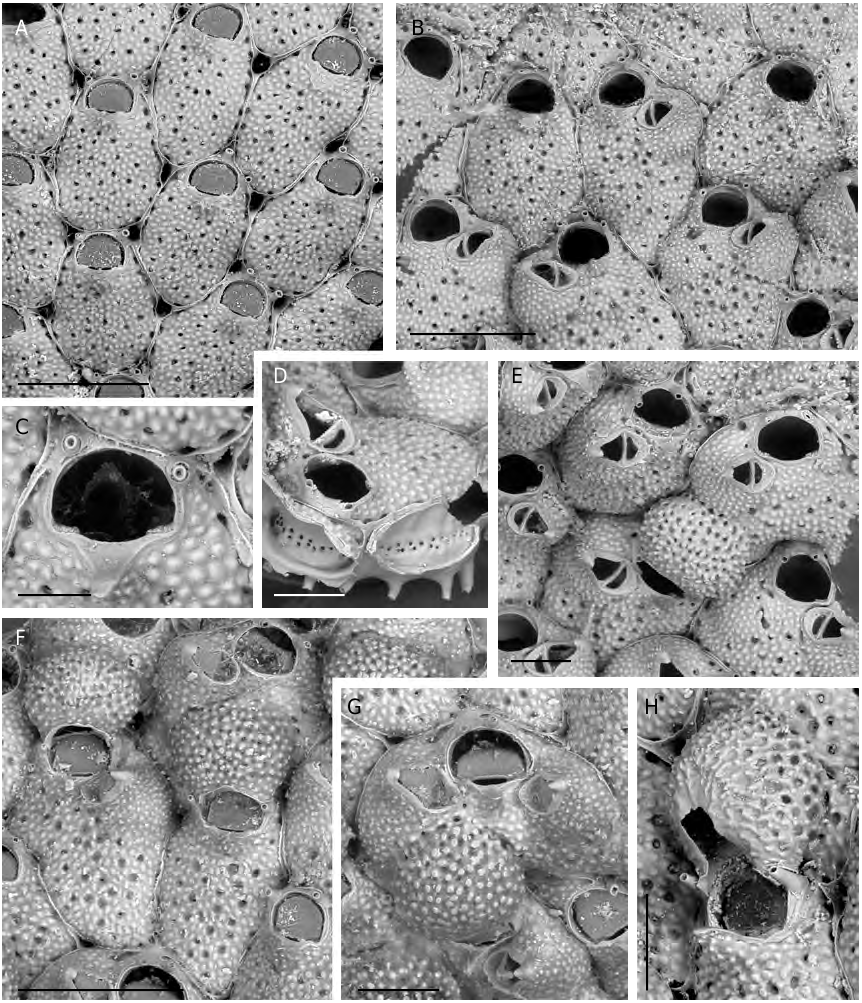

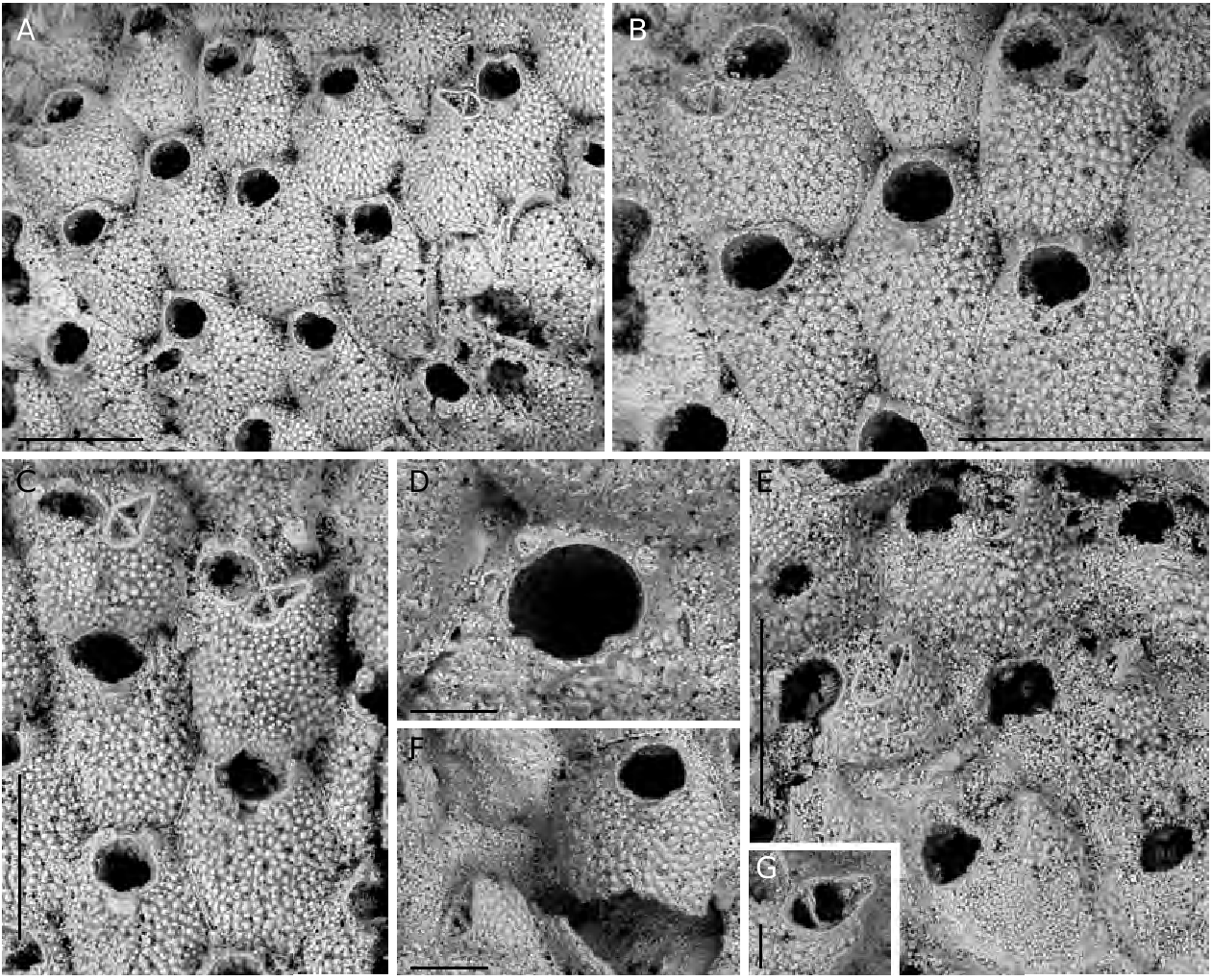

Bertorsonidra prenanti ( Gautier, 1955) n. comb. ( Figs 2 View FIG ; 3 View FIG ; 4A View FIG )

Tremopora prenanti Gautier, 1955: 236 , pl.1, figs 6-8.

Rhamphostomella argentea – Gautier 1962: 160. —? Zabala 1986: 438. —? Zabala & Maluquer 1988: 124, fig. 275.

Non Schizoporella argentea Hincks, 1881: 158 , pl. 9, fig. 6a, b.

Non Robertsonidra argentea View in CoL – Ryland & Hayward 1992: 261, fig. 19b. — Tilbrook 2006: 261, pl. 57E, F.

Hippoporina sp. – Di Geronimo et al. 1994: 102, part.

Rhamphostomella View in CoL (?) prenanti – d’Hondt & Ben Ismail 2008: 63.

MATERIAL EXAMINED. — Algeria. Castiglione, 22.IV.1952, unique colony, holotype ( MNHN, J. Picard collection).

Western Sicily. Egadi Islands, Marettimo Island, South of Bassana Point, sample EBE. 4, 19 m depth, 4 fragments, seemingly from a single, living, fertile colony (PMC. R. I. H. B9a). — Egadi Islands, north of the Levanzo Island, off Cape Grosso, samples ELE.7 and ELI.7, respectively sampled during summer and winter seasons, 17 m depth, 5 fertile and sterile fragments (PMC. R. I. H. B9a).

Case Catarinicchia section, early Pleistocene, sample BC7, 1 specimen (PMC. R.I.Ps. B9a).

Central-eastern Sicily. Basal bioclastic layer of the Pianometa section, early Pleistocene, 1 fertile specimen (PMC. R.I.Ps. B9b).

North-eastern Sicily. East of Furnari, Contrada Inferno, Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto Basin, middle-late Pliocene or?early Pleistocene, sample MC.116, 1 specimen (PMC. R.I. B9c).

DESCRIPTION

Colony encrusting multiserial and unilaminar, orange to salmon in colour, loosely attached to the substratum and elevated from it through regularly spaced, mineralised, short, hollow, pillar-like structures emanating from the basal surfaces, mostly from the periphery, of each zooid ( Fig. 2D View FIG ).

Autozooids oval to rhomboidal, slightly convex, separated by distinct grooves and a thin raised suture, usually leaving irregularly-shaped lacunae where three zooids come into contact ( Fig. 2A, F View FIG ). Frontal wall coarsely tuberculate with a peripheral row of relatively large, elongated pores plus 18-28 rounded infundibular ones, scattered on the frontal surface ( Fig. 2A, B View FIG ). Orifice located very distally, slightly wider than long with a semicircular distal rim, lined by a thin distal shelf, and a straight proximal lip; sinus very shallow and wide, occupying more than half of the proximal edge, flanked by squared and shallow slightly denticulate condyles ( Figs 2B, C, E View FIG ; 3D View FIG ). A thin peristome sometimes develops, raised on the anter, shallowing laterally to level orifice at proximal corners. One to three, usually two, inconspicuous slender spines, not articulated at the base, characteristically very distal at each side, or asymmetrical ( Figs 2 View FIG A-E; 3A, B, D), two persisting in ovicellate zooids, usually slightly displaced proximally ( Figs 2E, F, H View FIG ; 3C View FIG ). An elevated, pointed, slightly asymmetrical umbo present on most autozooids (mostly obvious in Fig. 2C, H View FIG ); its surface evenly tuberculate, except for the truncated, smooth, distal side.

Avicularium single, often lacking, lateral-suboral on an inflated imperforate cystid; rostrum acute to the frontal surface and laterally directed, typically elongate triangular with a hooked tip; cross-bar complete, strong and slightly arched ( Figs 2B, E View FIG ; 3 View FIG A-C, F, G). Paired avicularia observed in a single zooid ( Fig. 2G View FIG ).

Ovicell globular, prominent, recumbent on and slightly immersed in the frontal wall of the distal zooid, slightly wider than long and restricted near the opening, overarching the zooidal primary orifice ( Figs 2E, F, H View FIG ; 3C View FIG ), seemingly semicleithral or cleithral sensu Ostrovsky (2008). It has an entirely membranous ectooecium and a calcified entooecium sculptured by evenly distributed small pseudopores located within depressions in between smooth truncated tubercles; the proximal margin lined by a thin slightly raised edge ( Figs 2F View FIG ; 3C View FIG ).

Communication of contiguous zooids through 12-20 pores irregularly arranged in longitudinal band just below the midline of the vertical walls between adjacent zooids ( Fig. 2D View FIG ).

Ancestrula not observed.

Measurements

Zooidal lenght: 637 ± 66 (549; 858) n = 34; zooidal width: 412 ± 57 (315; 582) n = 34; orifice length: 124 ± 8 (108; 139) n = 34; orifice width: 152 ± 12 (128; 179) n = 34; ovicell length: 308 ± 44 (246; 368) n = 9; ovicell width: 379 ± 18 (363; 408) n = 9; avicularial length: 158 ± 20 (117; 183) n = 11; avicularial width: 90 ± 15 (63; 109) n = 11.

VARIABILITY

The above description is exclusively based on living specimens. Several skeletal characters contribute to the intraspecific variability: the size of zooids and the zooidal outline and morphology, including calcification of the frontal wall and sculpture development; the presence and strength of the suboral umbo; the size and proportions of orifices; the number of oral spines (up to 4 in few zooids and 5 in a single one on the type material) and, most obviously, the presence or absence of avicularia in large parts of the colony.

Differences in skeletal preservation caused by biostratinomic mechanical stresses and by partial dissolution and extensive re-crystallization during fossilization often hamper the reliable attribution of fossil specimens to species-level taxa, as recently remarked by Berning (2006). Nevertheless, in the fossil specimens of R. prenanti , the well-preserved distinctive frontal wall morphology, together with the partial or complete preservation of orificial spines and even of condyles (usually absent from most zooids, seemingly due to their thinness and/ or a different mineralogical composition) on at least single zooids in a colony, allow for an identification to species level. Representatives of the fossil populations appear very close to the living ones. Only few differences between the fossil and the Recent specimens have been detected, which have been considered as intraspecific variability. They include the slightly distal position of the lateral-suboral avicularia, which are laterally or slightly disto-laterally directed; and the relatively depressed ovicells, being less distinct from the distal zooid frontal wall (seemingly due to secondary calcification), tending to form a more V-shaped proximal border.

Interestingly, fossil specimens from Pianometa exhibit some ovicells, which have prominences in their central part, thus being somewhat reminiscent of the tubercolate ovicells of “ Ramphostomella argentea ”, as figured by Zabala & Maluquer (1988). Nevertheless, and apart from this character, both diagnosis and drawing of Zabala & Maluquer (1988: 123, fig. 275), are probably a conflation.

REMARKS

The species was formerly erected by Gautier (1955) as Tremopora prenanti although subsequently synonymised by the same author ( Gautier 1962: 261) with Schizoporella argentea Hincks, 1881 from the Indo-Pacific, following personal suggestions by M. Prenant and A. B. Hastings. Nevertheless, the Mediterranean species is only reminiscent of Robertsonidra argentea as described and figured by Ryland & Hayward (1992: 261, fig. 19b) and by Tilbrook (2006: 261, pl. 57E, F). In fact, Bertorsonidra prenanti n. comb., exhibiting a wide shallow sinus laterally marked by squared condyles, clearly differs from R. argentea , which is characterized by a primary orifice with a deep concave sinus not flanked by condyles. Furthermore, R. argentea shows two different kinds of lateral-suboral avicularia: 1) a smaller and relatively more common one opposite to the umbo, acute to the frontal plane, distally hooked and laterally directed; and 2) a larger and rarer but more diagnostic one, normal to the frontal plane and proximolaterally directed. In contrast, a single avicularium type seems to be present in the Mediterranean species: lateral suboral, laterally directed, with a hooked rostrum on a large and prominent cystid. Further differences include the colour of living tissue (yellowish-white in R. argentea ), the zooidal outline, and the number, extent and morphology of the marginal pores. But most important differences relate to the presence of an evenly porous zooidal frontal wall in B. prenanti n. comb. (see discussion below).

Bertorsonidra prenanti n. comb. also differs from “ R. argentea View in CoL ” recorded by Powell (1967: 169, pl. 2, fig. 10) from the Red Sea, which have rare obliquely and proximally directed large avicularia, and is actually a different further species, as suggested by Tilbrook (2006). Moreover, photo observation of the specimen labelled as Robertsonidra argentea View in CoL from an unknown Mediterranean locality in the Busk collection (BMNH 1963:4.18.33) but different from this species (see discussion in Tilbrook 2006: 262), proved that it is not even conspecific with B. prenanti n. comb. More detailed analyses are needed for its determination.

Bertorsonidra prenanti n. comb. seems also different from R. oligopus ( Robertson, 1908) View in CoL , the type species of Robertsonidra View in CoL , also synonymised with R. argentea View in CoL by Gautier (1962). Robertsonidra oligopus View in CoL , seemingly restricted to the west coast of North America, is characterized by a convex frontal wall with a suboral, medially-placed prominent umbo, a lateral oral avicularium usually distal-laterally directed, and an ovicell with a crenate margin ( Robertson 1908: 292, pl. 20, figs 50-52). Unfortunately, the primary orifice was not described in detail and drawings, including opercula, only allow to appreci- ate orifices, which are dimorphic in ovicellate and non-ovicellate zooids, both with a shallow sinus, and, noticeably, the absence of oral spines.

The attribution of B. prenanti n. comb. to the genus Ramphostomella , as suggested by Gautier (1962) and dubitatively by d’Hondt & Ben Ismail (2008) after examination of the unique known specimen from Algeria, is precluded. The genus Ramphostomella , in fact, possesses a centrally imperforate, umbonulomorph frontal shield and pronounced ridges between marginal areolae, markedly different orifice and ovicell (see Gordon & Grischenko 1994). In contrast, a strikingly similar morphological appearance and several characters are actually shared with species of the genus Robertsonidra Osburn, 1952 , except for the pseudoporous lepraliomorph frontal wall, that is not the case for Robertsonidra . Consequently, as none of the already established genera seems to share all the morphological features observed in the examined material Bertorsonidra n. gen. is here proposed to accommodate the species described by Gautier. Particularly, the presence of pores in the frontal wall has been considered enough for erecting the new genus, somewhat paralleling the criteria adopted for separating couples of confamiliar genera, such as the couple formed by Therenia David & Pouyet, 1978 and Herentia Gray, 1848 within the Escharinidae Tilbrook, 2006 (see Berning et al. 2008), and that formed by Buffonellaria Canù & Bassler, 1917 and Pourtalesella Winston, 2005 within the Celleporidae Johnston, 1838 (see Winston 2005, but also Berning & Kuklinsky 2008). Consequently, it could be suggested that also Robertsonidra and Bertorsonidra n. gen., sharing most of their characters and differing for the nature of their frontal walls belong to the same family. Nevertheless, as the genus Robertsonidra , including at least seven species, mostly from the Indo-Pacific area ( Bock 2002, but see above), had remained systematically unplaced (see Tilbrook 2006: 261), the erection of a new family Robertsonidridae n. fam. is here suggested for accommodating both Robertsonidra and Bertorsonidra n. gen. The new family shares some features, such as the concave to widely sinuate primary orifice and the frontal avicularia, with the Bitectiporidae MacGillivray, 1895 (as reported by Hayward & Ryland 1999 and Ramalho et al. 2008) but differs for the ovicells with calcified entoecium and ectooecium, which remain unfused. In contrast, although special studies aimed to describe ovicells in both genera are needed, both Robertsonidra and Bertorsonidra n. gen. seem to possess ovicells with an entirely uncalcified ectoecium and appear consequently comparable to those in the family Schizoporellidae Levinsen, 1909 , mostly those of species belonging to the genus Schizoporella Hincks, 1877 .

FUNCTIONAL MORPHOLOGY

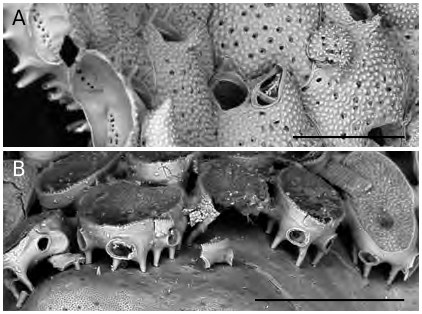

Colonies of B. prenanti n. comb. are loosely attached to their substratum through hollow, pillar-like structures ( Figs 3D View FIG ; 4A View FIG ), already described and figured by Gautier (1955: figs 7, 8), which emanate from the basal surfaces of each zooid. Th ese structures, mostly originating from the zooid periphery, elevate the basal surface of the colony some tens of micrometers above the substratum leaving a fissure-space above the algal tissue. Furthermore, it has been observed that the length of the rhizoidal pillars changes seemingly to better adapt the relatively thick and large colonial modules (zooids can reach about 900 Μm in length and 600 Μm in width: see measurements) to the curving or irregularly uneven morphology of the colonised surfaces. Finally, zooids are loosely connected each other and more or less wide lacunae exist in between them. All these features allow a certain articulation or at least some constructional flexibility to be attained. Consequently, colonies are able to grow nearly flat, thus partly levelling the irregularities of the colonised surfaces, when encrusting rough substrata, and to cover surfaces which are flexible or fleshy for the presence of soft tissues possibly without being particularly dangerous or lethal for the overgrown organism, due to their loose attachment. Th e presence of basal pillar-like attachment structures is not exclusive of B. prenanti n. comb. but has been observed also in similar, possibly related species, such as those belonging to Robertsonidra (see Robertson 1908; Tilbrook 2006). Furthermore, comparable basal extensions are present in species of the Hiantoporidae Hiantopora and the Microporidae Mollia ( Fig. 4B View FIG , AR pers. obs.), as already observed by Gautier (1955) himself and Berning (2006).

DISTRIBUTION

Bertorsonidra prenanti n. comb. is presently known only from a restricted area in the present-day and past Mediterranean. Living specimens originate from the southern part of the western Mediterranean: the colonies described by Gautier (1955, 1962) and recently listed by d’Hondt & Ben Ismail (2008) were sampled at Castiglione ( Algeria), and those herein described come from the Egadi Islands located West of Sicily. Additional material is from off Tabarka, western Tunisia (Harmelin, pers. comm., December 2008). Noteworthy, the species is apparently absent from the eastern side of Sicily (Ionian Sea), which was extensively examined for bryozoans ( Rosso 1996a , b; Rosso et al. 2008, 2010 and pers.obs.) and other western Mediterranean localities (see Gautier 1962; Harmelin 1976), as also discussed by Zabala (1986) and Zabala & Maluquer (1988). Similarly, no bryozoan review from the Adriatic (Novosel & Požar-Domac 2001; Hayward & McKinney 2002) and the Aegean Sea ( Harmelin 1968, 1969; Hayward 1974) reported this species.Furthermore, all available fossil specimens come from Sicily.

The Egadi specimens were found detached from their substrata or attached to corallinacean and peyssonneliacean algae, except for a single colony fragment encrusting a sponge. Material invariably originated from (pre)coralligenous bottoms, ranging from 17 to 19 m in depth. This environment is characterized by the abundance of algae, mostly encrusting corallinales, peyssonneliaceans, the chlorophyceans Halimeda tuna (J.Ellis & Sol.) J.V.Lamour. and Flabellia petiolata (Turra) Nizam. , the scleractinians Leptosammia prouvoti Lacaze- Duthiers, 1897 and Astroides calycularis (Pallas, 1766) View in CoL and gorgonaceans, among which Eunicella cavolini (van Koch, 1887) View in CoL . Bryozoans are abundant and diversified including ubiquitous and typical coralligenous species such as Scrupocellaria delilii (Audouin, 1826) View in CoL , Beania spp. , Pentapora ottomuelleriana (Moll, 1803) View in CoL , Margaretta cereoides (Ellis & Solander, 1786) , Rhynchozoon neapolitanum Gautier, 1962 View in CoL , and locally, Adeonella calveti Canù & Bassler, 1930 View in CoL , Myriapora truncata (Pallas, 1766) View in CoL and Reteporella grimaldi (Jullien, 1903) . Colonies of B. prenanti n. comb. from Algeria, sampled from between 30 and 40 m, encrusted nodular calcareous algae ( Gautier 1955, 1962).

Noteworthy, the same kind of substratum was utilised by the three specimens of B. prenanti n. comb. found in fossil assemblages, which can be interpreted as living in a depth range deeper than 10- 15 m and shallower than about 40 m. Particularly, the Pianometa colony was one of the extremely rare bryozoans from bioclastic cobblestones rich in centimetre- to decimetre-sized rhodoliths, and encrusted a corallinacean alga. Rhodoliths, whose nuclei consist of large fragments of the scleractinian Cladocora caespitosa (Linnaeus, 1767) , were deposited in pyroclastite layers in very shallow waters ( Pedley et al. 2001; AR pers. obs.). Similarly, the colony from Contrada Inferno along the Mazzarrà stream from NE Sicily, was found on a sub-spherical rhodolith sampled in a polymictic conglomerate layer, including pebbles and cobbles, sometimes coated by algae and rarely colonised by bryozoans (AR pers. obs.). Finally, the colony from the Belice section comes from silty-sandy layers, relatively rich in bioclasts, small rhodoliths and algal coatings on large mollusc shells, interpreted as derived from a Coastal Detritic Biocoenosis (sensu Pérès & Picard 1964) developed at about 40 m depth. Bryozoans include dominant Cellaria spp. internodes, together with Reteporella couchii (Hincks, 1878) , Smittina cervicornis (Pallas, 1766) , Pentapora fascialis (Pallas, 1766) , Entalophoroecia deflexa (Couch, 1844) , Platonea stoechas Harmelin, 1976 and Buskea nitida (Heller, 1867) . Some other species, such as lichenoporids, Copidozoum planum (Hincks, 1880) , C. tenuirostre (Hincks, 1880) and Micropora coriacea (Johnston, 1847) were found, also encrusting corallinaceans ( Di Geronimo et al. 1994).

From the above reported data, it follows that B. prenanti n. comb. seems to have a restricted geographic range and that it is extremely rare both in the geological past and nowadays. Interestingly, the species has maintained sensibly unaltered its ecological requirements through time, being selective of the Coralligenous Biocoenosis sensu Pérès & Picard (1964), although seemingly not excluded from other bioconcretions.Such a feature makes this species an useful tool for palaeoecological inferences.

The stratigraphic range of B. prenanti n. comb. includes at least the middle part of the Early Pleistocene, as the Pianometa and the Belice layers were presumably deposited during the Emilian ( Pedley et al. 2001) and the Sicilian (see Sprovieri & Cusenza 1972; Di Geronimo et al. 1994), respectively.

Nevertheless, it could not be excluded that the species appeared earlier than this. The B. prenanti n. comb. bearing layers from the Contrada Inferno have not been dated due to the absence of stratigraphic markers, but sedimentation in the area (Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto Basin) became in the Early Pleistocene and locally date back since the Middle-Late Pliocene ( Messina 2003).

| MNHN |

Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle |

| R |

Departamento de Geologia, Universidad de Chile |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Bertorsonidra Rosso

| Rosso, Antonietta, Sciuto, Francesco & Sinagra, Alessandro 2010 |

Hippoporina sp.

| DI GERONIMO I. & COSTA B. & LA PERNA R. & RANDAZZO G. & ROSSO A. & SANFILIPPO R. 1994: 102 |

Robertsonidra argentea

| TILBROOK K. J. 2006: 261 |

| RYLAND J. S. & HAYWARD P. J. 1992: 261 |

Rhamphostomella argentea

| ZABALA M. & MALUQUER P. 1988: 124 |

| ZABALA M. 1986: 438 |

| GAUTIER Y. V. 1962: 160 |

Tremopora prenanti

| GAUTIER Y. V. 1955: 236 |

Schizoporella argentea

| HINCKS T. 1881: 158 |