Cystonectae Monogastricae.

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4669.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:6E2F8FE4-4524-44B1-B5F8-BCC58D4FDF8E |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3796978 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0384A837-8275-FFEB-FF37-F92BFAF378ED |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Cystonectae Monogastricae. |

| status |

|

Cystonectae Monogastricae. Family Cystalidae .

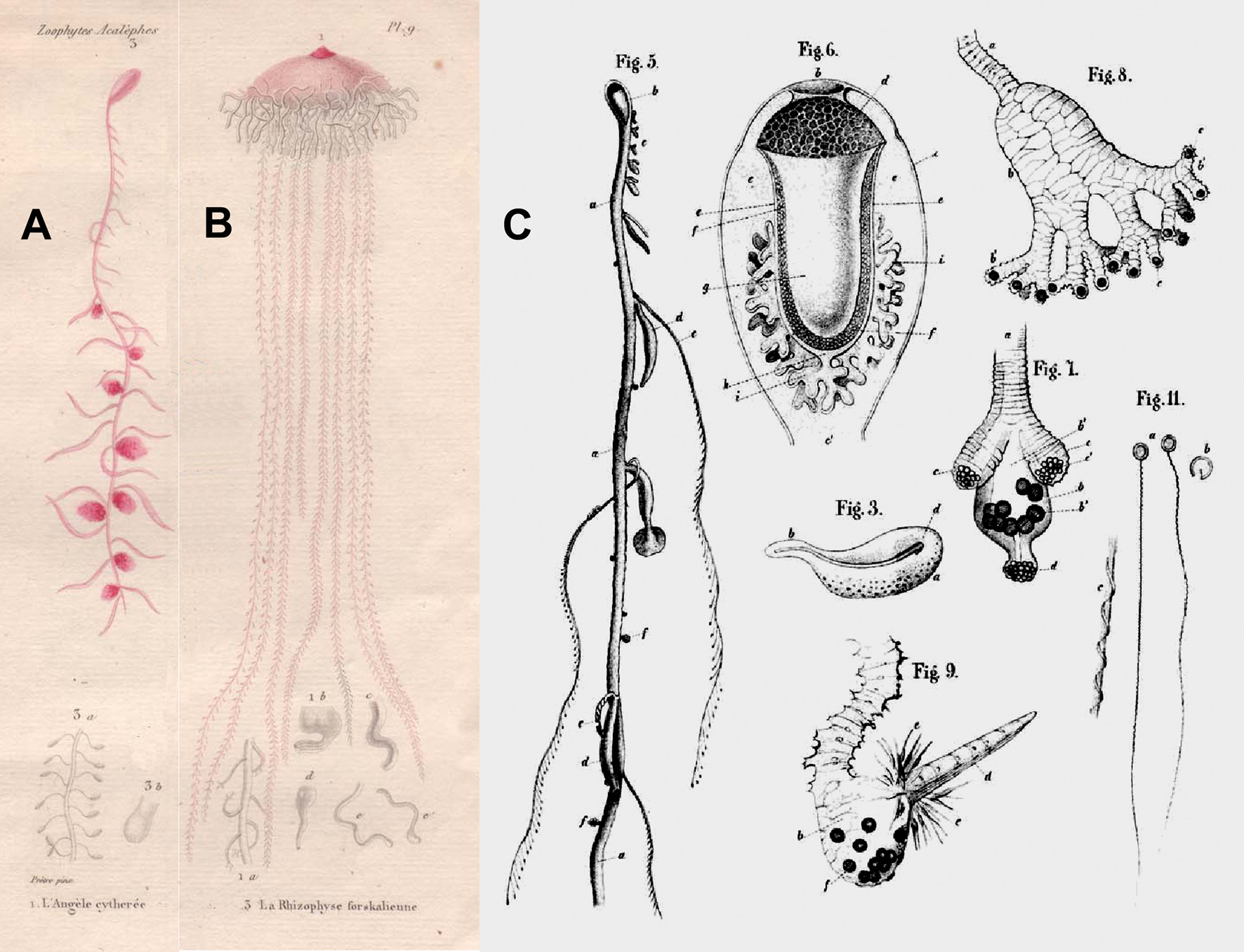

For the suborder Cystalidae , with its single genus Cystalia, Haeckel firstly mentioned the species C. larvalis Haeckel, 1888a , and then a specimen from the Challenger Expedition that he named C. challengeri . But he then 48 Original quote: “Der ältere Chun’sche Name wäre also dem Haeckel’schen aus Prioritätsrücksichten vorzuziehen, doch müsste er, den Regeln gemäss, in Pneumatophorae umgewandelt werden. Da mit diesem Namen aber bereits ein einzelner Anhang, die Schwimmblasen, bezeichnet wird, die Verwendung des Wortes Pneumatophoren also zu Missverständnissen Anlass geben würde, so tritt der zu zweit aufgestellte Haeckelsche Name Cystonectae (die von mir vorgeschlagene Modification in Cystophorae entspricht nicht den Nomenclatur regeln) in Verwendung. Der neueste, von Chun 97a aufgestellte Name: Rhizophysaliae ist selbstverständlich ganz überflüssig. Wenn Chun meint, als Begründer der Gruppe eine Änderung des Namens vornehmen zu dürfen, so verweise ich auf die Nomenclaturregeln, wo in § 5 sub b steht: »Einem einmal veröffentlichten Namen gegenüber steht dem Autor nur dasselbe Recht zu wie jedem andern Zoologen«.” concluded that (1888b, p. 314): “A closer comparison of them makes it very probable that these two species are identical; the more significant name Cystalia monogastrica may, therefore, be retained for both”. Thus, Haeckel had managed to establish three different names for the same species. Haeckel (1888b, Plate XXII) gave five illustrations of C. monogastrica (see Figure 20 View FIGURE 20 ), but he himself recognised that the first four of his figures represented larval stages in the development of a siphonophore with a pneumatophore, which he, at first, suggested might have belonged to an agalmatid. Indeed, he concluded (ibid. p. 315): “Since I was not able to recognise the origin of these pelagic larvae, nor to follow their further development, the question remains open, whether they were produced by a Physonect or a Cystonect. In the latter case they may possibly have been derived either from Cystalia or from the closely allied Epibulia ”. So even he was uncertain that these larvae belonged to his Cystalia . The fifth illustration he considered (ibid. pp. 314-315): “might be only a young form or a monogastric larva of the polygastric Epibulia ritteriana ” (see below). However, he then countered that suggestion by noting that hypocystic villi where absent in his Cystalia but were present in Epibulia and, indeed in all rhizophysid cystonects.

From his description of Cystalia monogastrica , based on his figure 5 (see Figure 20A View FIGURE 20 ), we can note the prevalence of red pigmentation, especially in the gonodendron. Haeckel (1888b, p. 317) said: “Gonodendron (fig. 5, gd).—The single large clustered gonodendron, which is attached to the base of the siphon, on its ventral side, is similar to that of the Rhizophysidae . The gonostyle is richly branched, and each ultimate branch bears a single gonopalpon on its distal end (PI. XXIII, fig. 8, gq) and above it a single medusiform gynophore (f) and a cluster of several (four to eight) ovate androphores (h)”. However, the gonodendron that Haeckel was referring to was that of another of his new species, Nectophysa wyvillei , which will be discussed below. Nevertheless, it is clear that Haeckel’s interpretation is completely wrong. What he referred to as the female gonophore (gynophore, f) is actually the asexual medusoid that is subterminal on all the branches of either the male or female gonodendron of rhizophysid cystonects.

The tentacle of Cystalia monogastrica bore simple filiform tentilla, and there was also a (ibid. p. 316) a “corona of palpons”. Thus, as we will discuss further with regard to the Family Epibulidae , we have a specimen that, in its coloration and the structure of the tentilla, greatly resembles a much contracted specimen of Rhizophysa eysenhardtii , where the corona of palpons are simply young gastrozooids that have not yet developed their tentacles. On the other hand there are no hypocystic villi below the pneumatophore, a feature particularly noted by Haeckel. It is possible, as the specimen is so young, that they have yet to develop, and further observations on young specimens are needed before this can be resolved, but all mature specimens of the rhizophysid species currently recognised possess these structures.

Nonetheless, there appears to be little reason to consider Cystalia monogastrica a valid species and so, in order to remove it from any further discussion, let me summarise the considerations of later authors, although in actuality, Haeckel’s (1888b) description of Cystalia monogastrica has aroused very little interest. Schneider (1898, p. 172) 49, 50 merely remarked: “The fact that Cystalia monogastrica shows itself as nothing more than a young stage of Epibulia erythrophysa , probably requires no detailed discussion”. Bigelow (1911) rather strangely included both C. monogastrica and C. challengeri as junior synonyms of E. ritteriana , but included C. larvalis as only a questionable synonym; despite the fact that Haeckel had stated that they were all the same species.

Finally Totton (1965, p. 18) said: “I must point out that the only certainly known cystonect larva is that of Physalia . No reliance should be placed, except with great reserve, on certain figures of Haeckel’s purporting to be of this nature …. This specific name [ monogastrica ] is applicable only to figure 5 of Haeckel’s (1888b) plate XXII. The larvae, which he took in a tow net, Haeckel thought might belong to this species. Certainly no phylogentic [sic] arguments should be based on larvae of such doubtful parentage and identity … I have grave doubts about the existence of Haeckel’s Epibuliidae ”. That is quite suffient for the present author to say goodbye to Cystalia monogastrica !

As Figure 19 View FIGURE 19 shows, Haeckel (1888b) divided this suborder into two depending on whether the species had long, Macrosteliniae, or short siphosomal stems, Brachysteliniae, with each containing two families. For the former he divided the families according to whether the “cormidia” were monogastric, Family Rhizophysidae , or polygastric, Family Salacidae ; and for the latter by whether the “cormidia” were spiralled around the base of of a subvertical pneumatophore, Family Epibulidae , or were in a multiple series along the ventral side of a subhorizontal pneumatophore, Family Physalidae .

Cystonectae Polygastricae. Macrosteliniae. Salacidae .

Let us look at potentially the easier one first; namely the Salacidae , which are long-stemmed but were said to

49 Original quote: “Dass Cystalia monogastrica nichts als eine Jugendform der Epibulia erythrophysa vorstellt, bedarf wohl keiner eingehenden Erörterung.”

50 Delage & Herouard (1901, p. 244) appeared to attribute that statement to Chun (1897), but no such reference has been found in that paper.

possess polygastric “cormidia”, in which Haeckel (1888b) included only one genus and described only one species. The generic name Salacia was used, according to Haeckel, by Linnaeus (1746), but the date appears to be 1748, for the Portuguese Man O’War. However, Haeckel decided to revive it rather than give a new name to the genus. Haeckel, as noted above, suggested that the Rhizophysa uvaria of Fewkes (1886) probably belonged in the genus.

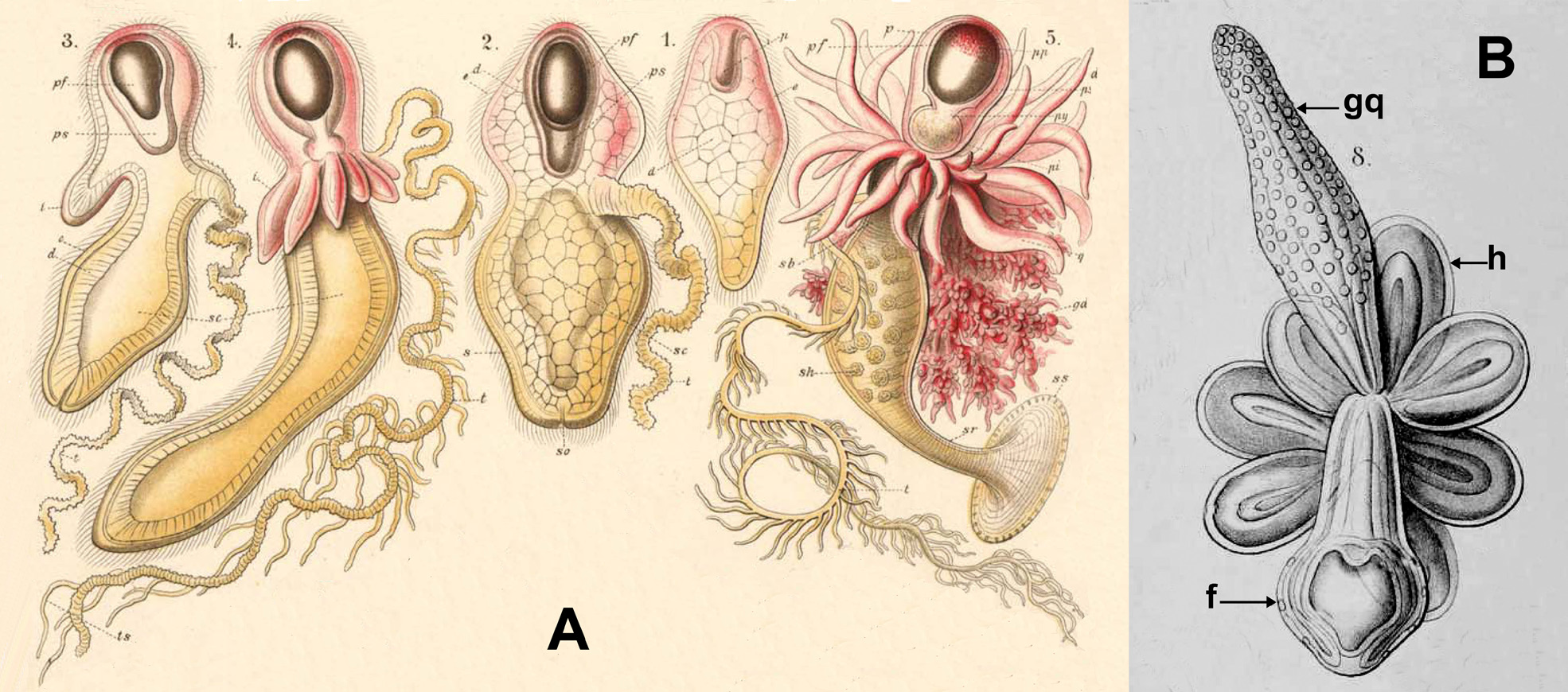

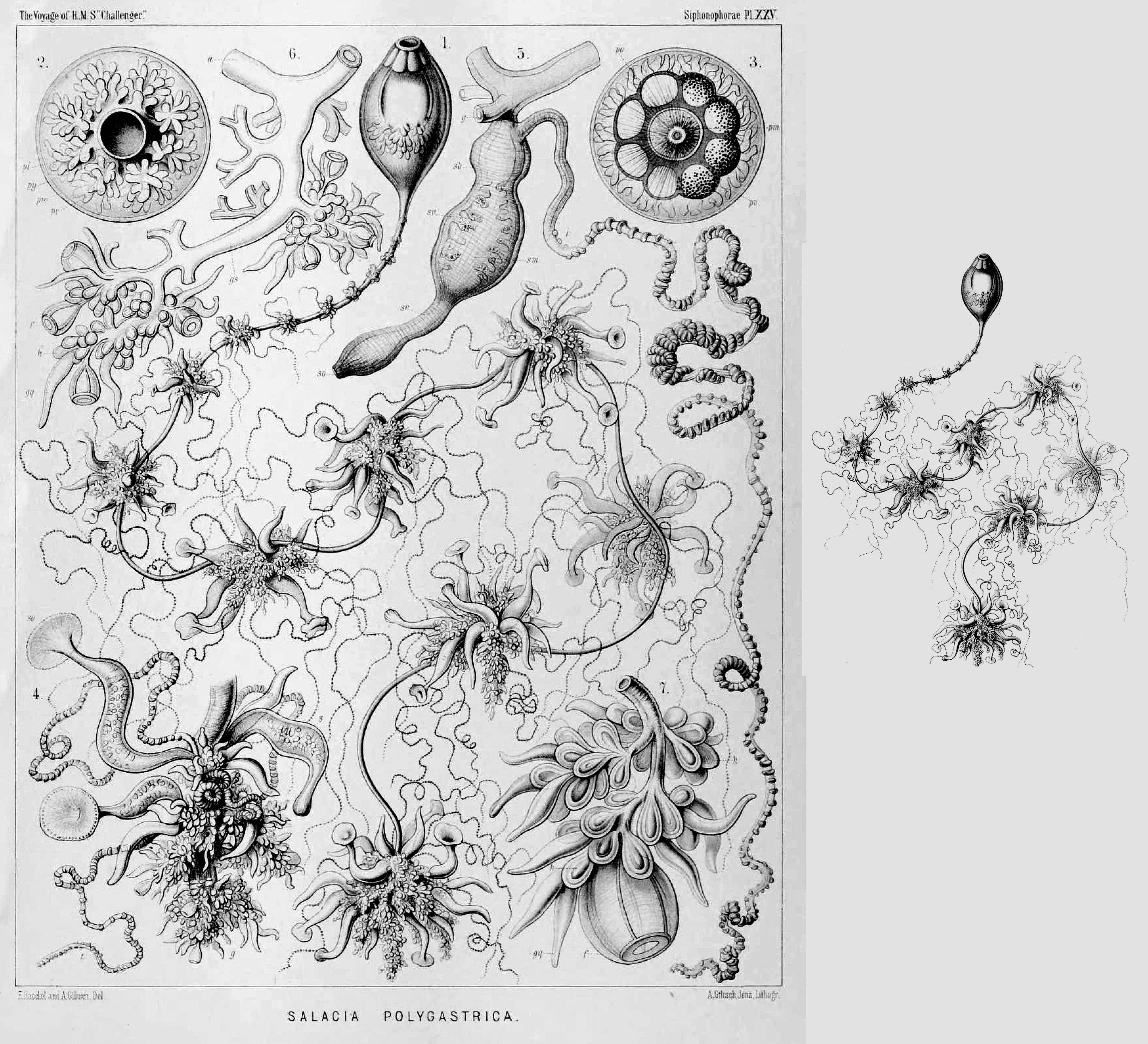

As with Cystalia monogastrica , we will follow the subsequent history of Salacia polygastrica in the hope that we can make an end of it. Chun (1897) retained Haeckel’s species and questionably equated Fewkes’s Salacia uvaria with it, while Schneider (1898), unsurprisingly, did the reverse by retaining Rhizophysa uvaria and synonymising S. polygastrica with it; for which Schneider was correct on the basis of precedence. Delage and Hérouard (1901) pointed out that the name Salacia was already pre-occupied by a calyptoblastic hydrozoan that Lamouroux (1816) had described in the early years of the 19 th Century, and thus they substituted the name Salacella for it. Bigelow (1911, p. 317), it seems, did not know of this, and considered the genus Salacia was monotypic for S. uvaria (Fewkes) , but all he said about it was: “I have not had the opportunity to study [it]”. After Bigelow the generic name Salacia /Salacella appears to have almost completely disappeared from the literature. However, Totton (1960, p. 346) in his Monograph on Physalia , stated that: “The only other siphonophore at all like Physalia is a remarkable specimen, now lost, taken by H.M.S. ‘Challenger’ and described by Haeckel (1888b) as Salacia polygastrica . … Haeckel not only named this delicate specimen - the stem measured only half a millimetre in diameter - which was ‟much contracted in the spirit bottle”, but he softened ‟it gradually with water to make it so elastic that it could be extended to that degree which is figured in (his) plate xxv, fig. 1” [quoted from Haeckel, 1888b, p. 331]. Haeckel’s idealized figure [see Figure 21 View FIGURE 21 ] showed a truly remarkable animal. No other specimen has ever been seen, but if such animals do exist they have many features in common with Physalia , from which they differ strikingly in the nature of their air-sac and by the fact that the “cormidia” are borne on a long stem. The existence of Salacella, if confirmed, would demonstrate conclusively that Physalia retains characteristics of larval forms such as are also found in physonect genera”. Totton made no reference to Fewkes’s specimen of S. uvaria .

Haeckel’s (1888b, p. 330) fascination with this “remarkable species” ( Figure 21 View FIGURE 21 ) was probably because, as is very evident throughout his Monograph, he was hell-bent on finding or, in retrospect, inventing, intermediate species. Thus (ibid.): “The family Salacidae is an interesting group intermediate between two very dissimilar families of Cystonectae , the macrostelious Rhizophysidaae ... and the brachystelious Physalidae ... It agrees ... with Physalia ... in the polygastric structure of the cormidia ... and ... especially in the structure of the siphons and the simple tentacles, bearing a series of reniform cnidonodes”. This is a somewhat strange statement for, although the gastrozooids and tentacles of the two species might resemble each other, Physalia is unique among siphonophores as most of its tentacle arises from a separate ampulla and not from the base of the gastrozooid. The specimen of Salacia polygastrica that Haeckel described was one of the few that were actually collected during the Challenger Expedition, and (ibid.): “The single specimen examined was so well preserved that it was possible by staining and dissecting it to recognise the essential structure of all the different organs”.

However, in Haeckel’s (1888b pp.331-332) short, seven paragraph description there is a certain lack of detail that belies the detailed illustrations (see Figure 21 View FIGURE 21 Left). Two of these paragraphs deal with the pneumatophore and the pneumatocyst and contain no information of taxonomic importance apart from the fact that hypocystic villi were present. The three paragraphs on the cormidia, siphons and tentacles tell us that (ibid.): “each ordinate polygastric cormidium ... is a botryoidal cluster composed of about ten to twenty siphons and gonodendra, each siphon provided with a long simple tentacle”; that palpons were “possibly” present, although the difference between them and the gastrozooids “does not seem as sharp, as in Physalia ”; the tentacles bore no tentilla; while the gonodendra were monoecious, as both “gynophores” and “androphores” were present. The remaining paragraph contained details of the corm, and it will be quoted below.

However, having apparently waxed so lyrical, although one must note the quotes form Haeckel that he made, Totton (1965, p.8) later said: “Haeckel’s Salaciidae [Salicidae in Haeckel] for Salacia polygastrica … should be dropped. I have mentioned (1954) the difficulty of accepting S. polygastrica ”. This again is rather strange as there does not appear to be any reference to S. polygastrica in Totton (1954) , and presumably he was referring to his 1960 monograph. Evenso, Totton’s 1965 statement does not seem to follow on from his earlier one, unless one appreciates the extreme subtlety of his sarcasm, which we will return to shortly. Totton (1965) then makes no further reference to the species or genus. Stepanjants (1967) also commented that if the existence of S. uvaria were to be confirmed, then the link between Physaliidae and Rhizophysidae through Salacella probably would become obvious. Daniel (1974, p.27), however, noted that: “ Totton (1960) doubted the validity of this genus and later he omitted it from the list of valid species of Siphonophora in his Synopsis (1965). The validity of Salacella will remain problematic and doubtful until fresh material is obtained”.

So are there any features of Haeckel’s (1888b) description and illustration of Salacia polygastrica that might help one to decide whether they are factually correct or just pure fantasy? Firstly, it should be remembered that Haeckel did not observe the living specimen as it was collected in a dredge that sampled the bottom fauna at a depth of 1990 fathoms during the Challenger Expedition. With such a sampling technique one would not expect that such a specimen would be in such a fine condition, as the above quote implied. However, it is likely that the specimen was caught close to the surface shortly before the dredge was retrieved and so may have suffered little damage.

Secondly, as Totton (1960) pointed out, the specimen was very small and had been preserved in alcohol. Although it was much contracted, Haeckel, by the means quoted above, managed to stretch it out; but even then its total length was then only 12–15 cm. To show just how truly remarkable, if not miraculous, was Haeckel’s feat of teasing out the specimen, Figure 21 View FIGURE 21 (Right) shows it approximately at actual size, as stated by Haeckel. Apart from the fact that it is very doubtful that one could in any way tease out a highly contracted specimen preserved in alcohol, to have achieved such perfection as Haeckel illustrated is wondrous!

Haeckel’s (1888b, p. 332) description of the terminal branches of the gonodendra was also rather strange in that he said that there was: “a single large gynophore (medusiform umbrella … the manubrium of which develops after the detachment), a clustered group of smaller club-shaped androphores ..., and a number of gonopalpons”. Firstly, how could he possible know that the manubrium of the “gynophore” developed after its release, when he was dealing with a preserved specimen? We have already pointed out that Haeckel was mistaken in considering this subterminal medusoid as a female gonophore (gynophore) rather than what it actually is, an asexual nectophore that never develops a manubrium, which would, at least, make the specimen dioecious, as are all cystonects.

As in all of Haeckel’s (1888b) descriptions, that of Salacia polygastrica is totally unsatisfactory and, although the illustrations are beautiful, as are many others in his Challenger Monograph, they appear to be the result of Haeckel’s intent on finding an intermediate species, in this case linking the Physaliidae and the Rhizophysidae , such that their veracity and accuracy must be called into question. But can the species be synonymised with any currently recognised cystonect? Because Haeckel did not describe the presence of ptera on the gastrozooids and, because of its small size, one could assume that the specimen was probably a young Rhizophysa species. However, neither Rhizophysa . filiformis or R. eysenhardtii have tentacles without tentilla; this character having been found only for Bathyphysa conifera . Nonetheless, the tentilla are fragile structures and can easily break off or “dissolve” in the preservative, as the present author has witnessed for specimens of R. filiformis , and there are many descriptions of species whose tentacles are said to be without tentilla that subsequently have been shown to be incorrect. In that case, the presence of well-developed gonodendra, even on the more anterior region of the siphosome, would suggest that S. polygastrica could be synonymised with R. eysenhardtii . However, the one major difference is that the “cormidia” were said to be polygastric. This does set Salacia apart from all rhizophysids, while showing a close relationship with Physalia . Nonetheless, the present author is led to the same conclusion as Totton (1965) in that Haeckel’s description of S. polygastrica , like Fewkes’ (1886) Rhizophysa uvaria , is too unreliable for it to be considered as valid species.

Cystonectae Polygastricae. Family Rhizophysidae .

With regard to Haeckel’s (1888b) Family Rhizophysidae , the first thing ones notes is the absence of any reference to the genera Bathyphysa or Pterophysa . This is because he placed those genera in his physonect family Forskaliidae . He seems to have linked his statement (ibid. p. 237) that: “the Forskalidae are the largest and most splendid of all Physonectae ” with another (ibid.) stating that a: “very remarkable and gigantic deep-sea Physonect, which probably belongs to this family, was described in 1878 by Studer”, namely B. abyssorum . Haeckel stated that he re-examined Studer’s specimen and commented that (ibid. p. 248): “The proximal or superior half is only 3 to 5 mm. in diameter and is the trunk of the nectosome; it bears at its apex an ovate pneumatophore of 20 mm. in length, and beyond it numerous lateral apophyses (not mentioned by Studer, but figured by him in fig. 28, loc. cit.), which are probably the bases of the pedicles of the detached and lost nectophores”. This unlikely interpretation is made even more so if one accepts the present author’s suggestion that Studer assembled his two pieces of siphosome in the wrong order, as illustrated above!

Haeckel suggested that Fewkes (1886) Pterophysa grandis probably belonged to the same genus and mentioned some fragments of a large forskaliid from the Challenger Expedition that he provisionally called B. gigantea , which is a nomen nudum as he never actually described it. He believed that these species bore bracts not only on the stem itself but also on the long peduncles of the gastrozooids; hence the link to the family Forskaliidae . The pea-shaped bumps that Studer had noted on these peduncles and which he found to be filled with nematocysts were interpreted by Haeckel as the attachment points for bracts. Haeckel also hypothesised that not only had nectophores once been present, but that palpons probably had existed between them. Such flights of fancy, based on no evidence whatsoever, are, unfortunately all too prevalent in Haeckel’s (1888b) Challenger monograph. Presumably, this one derived from the fact that Forskalia species do have bracts attached to the peduncles of the gastrozooids, and Haeckel’s false belief that palpons or tentacles were attached to the nectosome in his genus Forskaliopsis ; rather than what happens in actually, in that the palpacles, attached to siphosomal palpons, stretch up between the nectophores.

Although so far we gave got away lightly with regard to the genus Bathyphysa , we will not be so lucky with the genus Rhizophysa that, with the exclusion of the former genus, should have been the only one in the family Rhizophysidae . Not so, Haeckel (1888b) included six genera! The following key shows how he distinguished between them:

1. “Cormidia” ordinate, separated by free internodes. Gonophores attached to the stem immediately on the base of the siphons............................................................................Subfamily Cannophysidae 2

- “Cormidia” loose. Gonostyles attached to the internodes of the stem, scattered between the siphons............................................................................. Subfamily Linophysidae 3

2. Tentilla simple, not branched.............................................................. Genus Aurophysa

- Tentilla trifid, with 3 terminal branches..................................................... Genus Cannophysa

3. Tentacles simple, without tentilla; or with simple, unbranched tentilla............................................ 4

- Tentacles always with a series of tentilla, all or some branched................................................. 5

4. No tentilla, tentacles simple................................................................ Genus Linophysa

- Tentilla simple, unbranched............................................................... Genus Nectophysa

5. Tentilla all trifid, with three terminal branches.............................................. Genus Pneumophysa View in CoL

- Tentilla polymorphous, partly simple, partly branched or palmate................................. Genus Rhizophysa View in CoL

The first characters that he used to split the family into two sub-families are basically what divide the genus Rhizophysa View in CoL into its two species, R. filiformis View in CoL and R. eysenhardtii View in CoL . The same could be said about the genera said to have trifid or polymorphous tentilla and those with simple tentilla. However, the total absence of tentilla would be very distinctive, if true. For the genus Aurophysa Haeckel simply mentions one species A. ordinata , from Ceylon, whose pneumatophore was capped with brown pigmentation; whose gastrozooids were orange; and whose gonophores were yellow. He compared his species with Studer’s (1878a) Rhizophysa inermis and noted (ibid. p. 324): “Studer tells us that this deep-sea form has no tentacles, but he describes and figures tentacles with a series of simple tentilla (fig. 10), apparently attached one to the base of each gonophore. I have no doubt that this was the usual tentacle, arising from the base of the siphon, strongly contracted and twisted around the base of the neighbouring gonophore”. As noted above the characters given suggest that the species is R. eysenhardtii View in CoL , but as it was neither described in detail nor illustrated it is yet another of Haeckel’s nomina nuda.

The other genus included in that subfamily was Cannophysa, in which he described the species C. murrayana Haeckel , and likened it to the species Fewkes (1882) described as Rhizophysa gracilis , which subsequent authors have considered to be a junior synonym of R. filiformis (e.g. Bigelow, 1911; Totton, 1965). Haeckel (1888b) gave a brief description, based on two specimens that he himself had collected off Lanzerote (Canary Islands), the smaller of which (see Figure 22, fig. 3) measured c. 15 cm in length. For the larger one he, yet again, produced stunning illustrations (see Figure 22). The pneumatophore was of the basic rhizophysid type, with an anterior pore, and numerous hypocystic villi. The gastrozooids and tentacles were rose in colour, and the latter were attached to the former on its dorsal or outer side; regarding which one might assume he was mistaken. Although Haeckel’s primary distinction of his cannophysid species was that the each gonodendron was attached close to the base of a gastrozooid, he gave very little information about it apart from saying (ibid. p. 326) that: “Each smallest group (or secondary gonodendron) is composed, as usual, of a single medusiform gynophore and a corona of club-shaped androphores, with a distal (rose-coloured) palpon”. With regard to their positioning, Haeckel said (ibid.) that each was: “attached to each node of the stem, immediately beyond the insertion of each siphon”; i.e. posterior to each gastrozooid. The key feature of his description and illustrations is the fact that tentacles bore tentilla with distinctly trifid distal ends. Haeckel made no reference to their similarity to the tricornuate type described by Gegenbaur (1853) on the tentacles of R. filiformis (compare Figures 12C View FIGURE 12 , fig.8 and 22, fig. 9), but one should be in no doubt that that was the species Haeckel was describing, although, surprisingly, some later reviewers did not reach that conclusion.

Haeckel (1888b) included four genera in his other sub-family, the Linophysidae , which included those species whose gonodendra were attached in the internodes between each gastrozooid. The first two genera were distinguished by the fact that tentilla were either absent, Linophysa , or were simple and unbranched, Nectophysa . Haeckel devoted just thirteen lines to the genus Linophysa , which contained only a single species, namely the Rhizophysa conifera of Studer, 1878. As usual Haeckel ignored the fact that, despite the change of genus, Studer was still the authority for the species that (i bid p. 271) he referred to it as “ Linophysa conifera Hkl. (= Rhizophysa conifera, Studer ”. Nevertheless, since the young gastrozooids of that species possess ptera it, thereby, belongs to the genus Bathyphysa , as has been discussed above. Thus we need not consider it any further.

The genus Nectophysa , with simple tentilla, contained two species, N. wyvillei Haeckel 1888b (see Figure 23) and N. eysenhardtii ( Gegenbaur, 1859) . Again the description of the former is brief. He noted that the stem was rose-coloured, as were the gastrozooids, tentacles and gonodendra. The tentilla were simple, and the gonodendra were attached midway between the gastrozooids. As usual, Haeckel made no comparisons with Gegenbaur’s species, except to note that they were closely allied. But really there is only one possibly good character that Haeckel described and that is the presence of filiform tentilla. There can be no doubt, as all subsequent reviewers agree upon, that Haeckel’s N. wyvillei is a junior synonym of Gegenbaur’s R. eysenhardtii .

The second group of Haeckel’s linophysids again included two genera, Pneumatophysa and Rhizophysa . For the genus Pneumatophysa Haeckel (ibid. p. 328) said: “The single known species of this genus, Pneumophysa gegenbauri [ Haeckel, 1888a], was observed by me in December 1881 in the Indian Ocean, and will be described on another occasion. A second species, similar to this, was noticed in my System der Siphonophoren … as Pneumophysa mertensii (= Epibulia mertensii, Brandt , 25, p. 33). But a closer examination of the excellent figures which its discoverer, Mertens, has left of this species, taken in the Tropical Pacific, has convinced me that it belongs to the following genus, Rhizophysa ”. Since Haeckel was one of the last to see these drawings by Mertens that shortly afterwards appear to have been lost and never seen again. Also, since Haeckel did not describe his P. gegenbauri then the species must become a nomen nudum.

Finally, in the genus Rhizophysa , the only rhizophysid genus that Haeckel did not himself establish, he included three species, Forsskål’s R. filiformis, Lesueur and Petit’s Rhizophysa planostoma [sic], and the aforementioned R. mertensii . There can be no doubt about the validity of Forsskål’s Rhizophysa filiformis , and we have already commented on R. planestoma , and suggested that it might be the same as R. eysenhardtii . However, Haeckel (1888b, p. 329) collected a specimen, off the Canary Islands, that he considered to be the same as the latter species, and he commented: “The structure of this Atlantic species, for which I retain Péron’s name, was very similar to that of the well-known Mediterranean form, the best description of which was published in 1854 [1853] by Gegenbaur [ R. filiformis ] … The Atlantic Rhizophysa planostoma [sic] differed, however, in the peculiar coloration (the pneumatophore, the stem, and the tentacles being rose-coloured, the siphons violet), and in the special form of the tentilla; the majority of these were trifid, with an odd median club and two paired lateral horns (similar to those of Cannophysa murrayana ) but scattered between them was a number of very large palmate tentilla, differing from those figured by Gegenbaur … mainly by a large purple ocellus on the convex outside; the peculiar calcarate tentilla, which Gegenbaur compared with a bird’s head in the Mediterranean Rhizophysa filiformis … were absent”. There can be little doubt, despite Haeckel’s reservations, that what he was describing was R. filiformis , if we accept the observation that R. planestoma had filiform tentilla. As for Brandt’s (1834) species mertensii was distinguished by Haeckel as having two different kinds of branches tentilla but, apart from that vague observation, no proper description has been published and, as noted above, it is not known if the illustrations of Mertens still exist.

Finally, the present author suggests that the fate of the eleven species that Haeckel (1888b) placed in the family

Rhizophysidae is as follows:

Family RHIZOPHYSIDAE Brandt, 1835 View in CoL

Sub-family CANNOPHYSIDAE Haeckel, 1888a

Genus Aurophysa Haeckel, 1888a

Aurophysa ordinata Haeckel, 1888a Nomen nudum

Aurophysa inermis = Rhizophysa inermis Studer, 1878 ? = Rhizophysa eysenhardtii View in CoL

Genus Cannophysa Haeckel, 1888a

Cannophysa gracilis = Rhizophysa gracilis Fewkes, 1882 = Rhizophysa filiformis View in CoL

Cannophysa murrayana Haeckel, 1888a = Rhizophysa filiformis View in CoL

Sub-family LINOPHYSIDAE Haeckel, 1888a

Genus Linophysa Haeckel, 1888a

Linophysa conifera = Rhizophysa conifera Studer, 1878 View in CoL = Bathyphysa conifera View in CoL

Genus Nectophysa Haeckel, 1888a

Nectophysa eysenhardtii = Rhizophysa eysenhardtii Gegenbaur, 1859 View in CoL

= Rhizophysa eysenhardtii View in CoL

Nectophysa wyvillei Haeckel, 1888a = Rhizophysa eysenhardtii View in CoL

Genus Pneumophysa Haeckel, 1888a View in CoL

Pneumophysa gegenbauri Haeckel, 1888a Nomen View in CoL nudum

Genus Rhizophysa Péron & Lesueur, 1807 View in CoL

Rhizophysa filiformis View in CoL = Physophora filiformis Forsskål, 1775 = Rhizophysa filiformis View in CoL

Rhizophysa planostoma [sic] Lesueur & Petit, 1807? = Rhizophysa eysenhardtii View in CoL Rhizophysa mertensii View in CoL = Epibulia mertensii Brandt, 1835 ? = Rhizophysa filiformis View in CoL

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

Cystonectae Monogastricae.

| Pugh, P. R. 2019 |

Aurophysa

| Haeckel 1888 |

Aurophysa ordinata

| Haeckel 1888 |

Aurophysa inermis

| Haeckel 1888 |

murrayana

| Haeckel 1888 |

Linophysa

| Haeckel 1888 |

Linophysa conifera

| Haeckel 1888 |

Nectophysa Haeckel, 1888a

| Wyvillei. Haeckel 1888 |

Nectophysa wyvillei

| Haeckel 1888 |

Pneumophysa

| Haeckel 1888 |

Pneumophysa gegenbauri

| Haeckel 1888 |

Rhizophysa gracilis

| Fewkes 1882 |

Rhizophysa inermis

| Studer 1878 |

Rhizophysa conifera Studer, 1878

| , Studer 1878 |

Rhizophysa eysenhardtii

| Gegenbaur 1859 |

Rhizophysa eysenhardtii

| Gegenbaur 1859 |

Rhizophysa eysenhardtii

| Gegenbaur 1859 |

Rhizophysa eysenhardtii

| Gegenbaur 1859 |

Rhizophysa mertensii

| Lesson 1843 |

RHIZOPHYSIDAE

| Brandt 1835 |

Epibulia mertensii Brandt, 1835

| , Brandt 1835 |

Rhizophysa Péron & Lesueur, 1807

| Peron & Lesueur 1807 |

Physophora filiformis Forsskål, 1775

| Forsskal 1775 |