Romerolagus diazi (Ferrari-Pérez, 1893)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625539 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625380 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03822308-B743-FFFC-FFDB-F5C7FC91F381 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Romerolagus diazi |

| status |

|

Volcano Rabbit

French: Lapin des volcans / German: Vulkankaninchen / Spanish: Conejo de los volcanes

Taxonomy. Lepus diazi Ferrari-Pérez, 1893 View in CoL ,

“near San Martin Texmelusan, northeast ern slope of Volcan Iztaccihuatl [Ixtaccthuatl, Puebla], Mexico.”

Whether or not the genus Romerolagus represents the most primitive of living leporids is still under discussion; or it is close to specialized leporids such as Syl vilagus, Oryctolagus , and Lepus ; or is intermediate. Romerolagus diazi has the putative ancestral karyotype (2n = 48), shared by all known species of Lepus and Sylvilagus bachmani . A recent study comparing allozymic variation among different leporids indicates that R. diazi is genetically more similar to Sylvilagus than to Lepus . Romerolagus diazi lives sympatrically with two species of Sylvilagus : S. cuniculariusand S. floridanus . A study showed that both taxa were found together in only 8% of their sympatric distribution, and R. diazi was more common at higher elevations than the species of Sylvilagus . Monotypic.

Distribution. C Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Distrito Federal, Morelos, and W Puebla states). View Figure

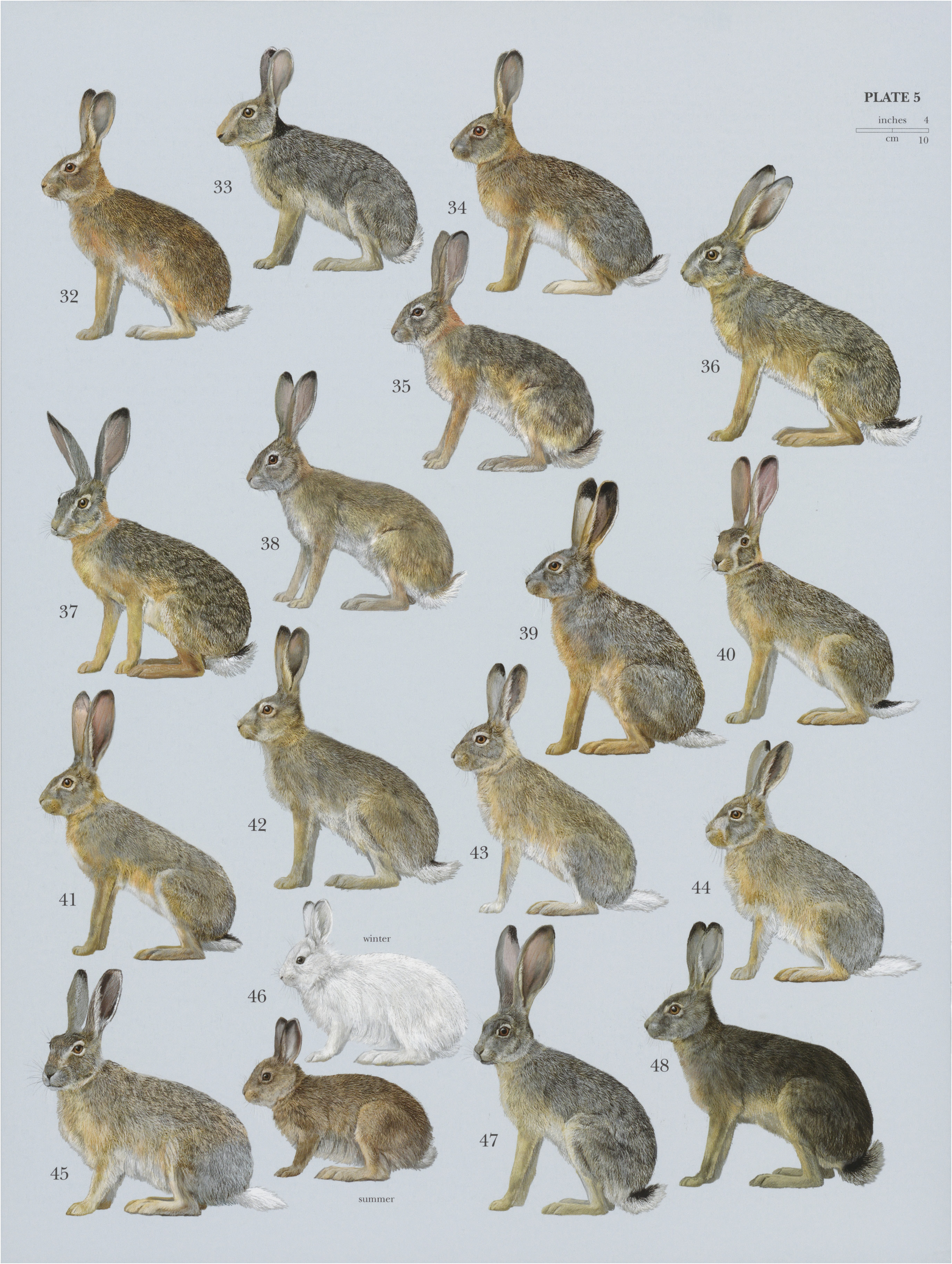

Descriptive notes. Head—body 230-350 mm, tail (vertebrae, not externally visible) 12-31 mm, ear 40-45 mm, hindfoot 40-55 mm; weight 387-602 g. The Volcano Rabbit is relatively small, with small and rounded ears. Hindlegs and hindfeet are short.

Tail is enclosed beneath skin, as in pikas ( Ochotona ), and is invisible externally. Fur is short and dense. Tail, dorsal pelage, and lateral pelage are dark brown to black. Feet are light buff above, and ventral fur is brown. Sides of nose and around eyes are light buff, and throat has tint of gray.

Habitat. Pine ( Pinus , Pinaceae ) forests with undergrowth of tall dense bunchgrasses (“zacaton”) and rocky substrates, interspersed with patches of deep, dark soil at elevations of 2800-4250 m. Volcano Rabbits occur at highest densities at elevations of 3150-3400 m and occupy areas with abrupt relief. Summer is warm and rainy; winter is cold and dry. Vegetation cover consists of open forest of mostly Montezuma pine (P. montezumae), intermixed with P. hartwegii, P. rudis, P. teocote, P. patula, and P. pseudostrobus (all Pinaceae ) up to 25 m tall. Understory has a dense ground cover oftall (up to 1-5 m), coarse, clumped bunchgrasses, mainly Muhlenbergia macroura, Festuca rosei, I. amplissima, and Stipa ichu (all Poaceae ). Volcano Rabbits also inhabit patches of dense secondary forest of alder ( Alnus arguta, Betulaceae ) up to 12 m tall, with some palm-like Furcraea bedinghausii ( Agavaceae ) up to 6 m tall. Shrub layer is up to 2:5 m tall, with heavy cover of a zacaton grass and herb layer. Volcano Rabbits temporarily colonize cultivated fields of oats ( Avena sativa, Poaceae ) when plants are half-grown in late July until they are harvested in early October. They use burrows with hidden entrances at bases of grass clumps. They probably do not actively dig their own burrows; it has been reported that they use abandoned burrows of the American Badger (Taxidea taxus), the Rock Squirrel (Otospermophilus variegatus), the Nine-banded Armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), and Merriam’s Pocket Gopher (Cratogeomys merriam). Hollows between rocks and boulders and large boulderstrewn sinkholes are used as temporary refuges.

Food and Feeding. Diet of the Volcano Rabbit consists of zacaton grasses, mainly Festuca amplissima, F. rosei, M. macroura, S. ichu, and Epicampes sp. (all Poaceae ). They select green and tender leaves of these grasses. A. arguta is a staple food. Spiny herbs (Cir sium, Asteraceae , and especially Eryngium , Apiaceae ) are also consumed. Forbs and shrubs are consumed mainly during the dry season. Oat and maize in cultivated fields are eaten during the rainy season.

Breeding. Reproductive season of the Volcano Rabbit may last throughout the year because pregnant females have been found in January—October and lactating females have been found in February-December. Reproductive peak is noticeable during the warm and rainy summer. In captivity, a male always selected the same female, but in her absence, he became interested in another female. Copulations were observed during the day. The male kept pace directly behind the female, occasionally nuzzling her hindquarters. The female turned back toward his flank, and both circled each other rapidly for several turns. The male then mounted the female and engaged in a series of rapid pelvic thrusts. Parturition always took place at night in captivity. Gestation lasts 38-41 days. Female Volcano Rabbits have postpartum estrus. Nests are found in April-September. Nest is a shallow hole excavated in the ground nextto the base of a clump of zacaton grass and averages 15 cm in diameter and 11 cm in depth. Outer nest materials are dry plant fragments of pine, alder, herbs, and zacaton grass; inside, the nest is lined and filled out with hairs from the mother. Entrance to the nestis covered with plant fragments. Usually, nests are on flat terrain consisting of deep soil. Only a few nests are found on rocky or steep substrates. Mean litter size is 2-1 young (range 1-5), within the range of species of Lepus butsignificantly different from largelitters of species of Sylvilagus and Oryctolagus . Female Volcano Rabbits have three pairs of mammae, but only four mammae, on average, produce milk. Newborns are completely furred, but their eyes are closed. Fur is dusky gray above and pale dull gray below. Tail is externally visible and hair-covered in newborns. Eyes of young open at 4-8 days of age, but they remain in the nest for c.14 days. Young start to feed on solid food in the third week after birth and gradually become independent of the nest. Young are still nursed while moving around with their mother.

Activity patterns. Volcano Rabbits are especially active in evening and early morning hours and usually rest quietly in the middle of the day. Nevertheless, large numbers of Volcano Rabbits have been observed outside their burrows between 11:00 h and 13:00 h.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Volcano Rabbitlives in groups of 2-5 individuals. Formation of social dominance hierarchies among groups of six individuals, with only one male and 1-2 females breeding, has been reported in seminatural enclosures. Playing, fighting, chasing, foraging, and sleeping among clumps of zacaton grass are primary aboveground daytime activities. Pellets regularly are found in groups near burrows and throughout runaways. The Volcano Rabbit frequently utters high-pitched penetrating calls; up to five different vocalizations have been described. Individuals utter a sharp call and scuttle away along a runway to a burrow when alarmed. Captive females were clearly aggressive to both sexes, but males never initiated aggression toward a female. Female—female aggression was much more frequent and violent than female-male aggression. The dominant individual was always a female. Captive individuals defend their own cage and chase intruders.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Volcano Rabbit is endemic to Mexico, and its distribution is restricted to three discontinuous areas of core habitat of ¢.386 km? on slopes of Volcan Pelado, Tlaloc, Popocatépetl, and Ixtaccithuatl. Present distribution is fragmented into 16 patches. A distributional survey suggested that Volcano Rabbits have disappeared from areas of the central Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt such as on Volcan Nevado de Toluca or eastern slopes of Ixtaccithuatl where it has been reported in the recent past. A study based on fecal counts and line transects (on horseback) estimated population size at 2478-12,120 individuals. The smaller estimate was recommended for conservation purposes due to broad confidence intervals. Reasons for decline are habitat destruction from increasing encroachment of agriculture up the slopes of mountains, forest fires, overexploitation of timber, cutting of zacaton grasses for thatch and brush manufacture, and human settlements. Large areas of zacaton grasses are burned each dry season to improve grazing for sheep and cattle, but effects of frequentfires are under assessment because new data suggest thatfires actually improve habitat of the Volcano Rabbit. Habitat loss has been estimated at 15-20% over the last three generations. Habitat fragmentation is caused by contiguous habitat loss and highway construction, causing fragmented populations to become genetically isolated and increasing risk of local extinction by random processes. Despite it being illegal under Mexican law, hunting by nearby villagers and people from Mexico City is also a concern. Nesting habits of the Volcano Rabbit make the young particularly vulnerable to predation by dogs and humans. Most localvillagers are unaware of the protected status of the Volcano Rabbit, and although it occurs in several national parks (e.g. Izta-Popo Zoquiapan National Park), hunting and grass burning still occur within their boundaries. One conservation action was establishment of a captive breeding program. The breeding program has been partly successful, but infant mortality has been high. Conservation recommendations are to focus on habitat management including control of burning and overgrazing of zacaton habitat and enforcement of the existing law prohibiting hunting and trade of the Volcano Rabbit. Education at local, national, and international levels about the protected status of the Volcano Rabbit should be improved, and zoos should take part in the breeding program to enhanceits success.

Bibliography. AMCELA, Romero, Rangel, de Grammont & Cuarén (2008), Barrera (1968), Cervantes (1980, 1982), Cervantes & Lopez-Forment (1981), Cervantes & Martinez (1992), Cervantes, Lorenzo & Hoffmann (1990), Cervantes, Lorenzo & Yates (2002), Davis & Russell (1953), De Poorter & Van der Loo (1981), Fa & Bell (1990), Fa et al. (1992), Granados (1981), Hoffmann & Smith (2005), Hoth et al. (1987), Hunter & Cresswell (2015), Leopold (1959), Lopez-Forment & Cervantes (1981), Rizo-Aguilar et al. (2015), Rojas (1951), Velazquez (1993, 1994), Velazquez & Heil (1996), Velazquez et al. (1993).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Romerolagus diazi

| Don E. Wilson, Thomas E. Lacher, Jr & Russell A. Mittermeier 2016 |

Lepus diazi Ferrari-Pérez, 1893

| Ferrari-Perez 1893 |