Sylvilagus transitionalis (Bangs, 1895)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625539 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625402 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03822308-B74E-FFF3-FA6E-F482F923F0AF |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Sylvilagus transitionalis |

| status |

|

New England Cottontail

Sylvilagus transitionalis View in CoL

French: Lapin de Nouvelle-Angleterre / German: Neuengland-Baumwollschwanzkaninchen / Spanish: Conejo de Nueva Inglaterra

Other common names: Wood Rabbit

Taxonomy. Lepus transitionalis Bangs, 1895 View in CoL ,

“Liberty Hill, Conn. [= New London Co., Connecticut, USA].”

Formerly, S. obscurus was included in S. transitionalis but received species status due to the discovery of two different cytotypes ( S. obscurus 2n = 42 and S. transitionalis 2n = 52). Monotypic.

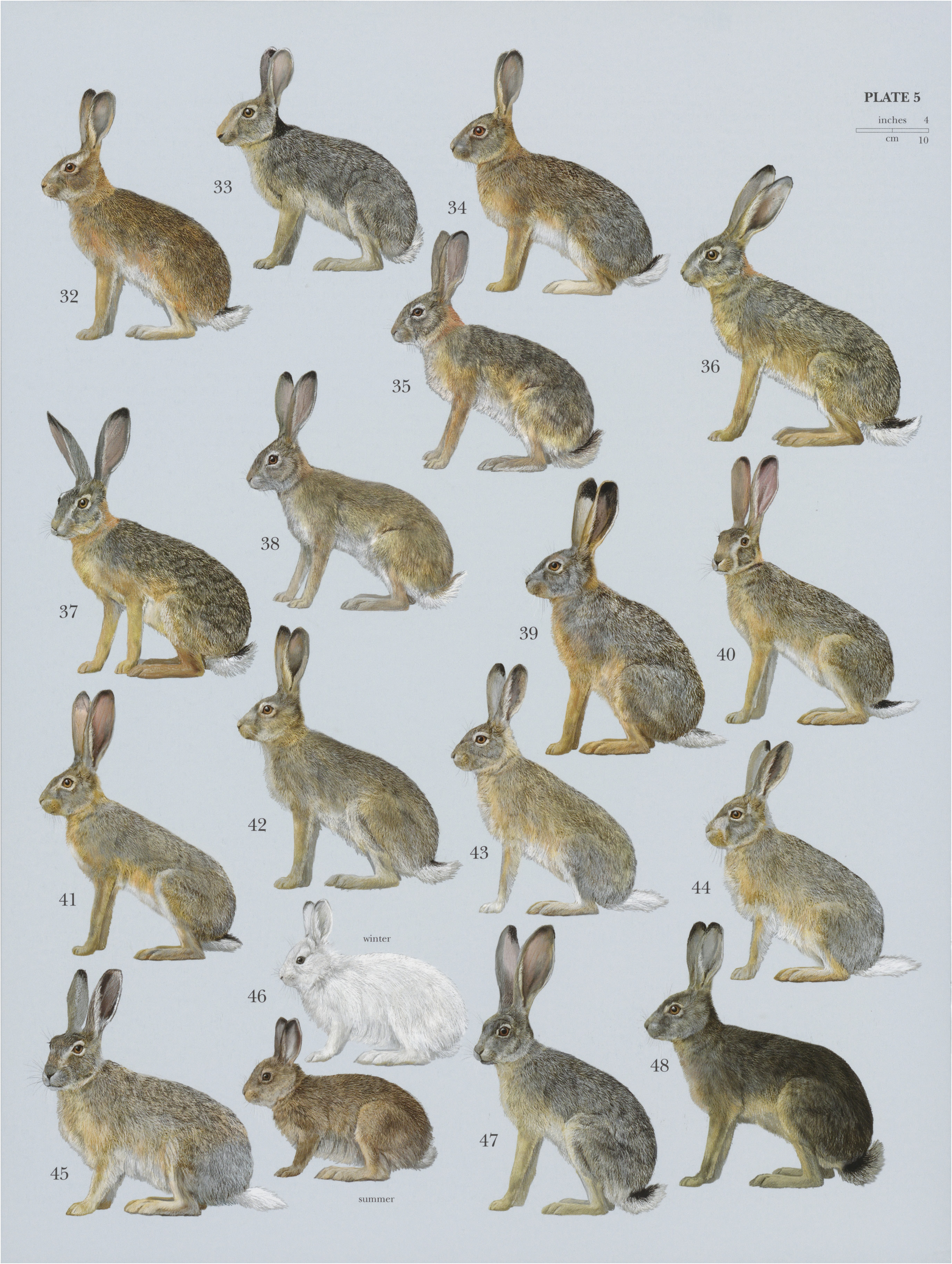

Distribution. NE USA,in coastal S Maine, coastal and Merrimack River valley region of S New Hampshire, SE New York, W Massachusetts (including parts of Cape Cod), W & E (E of the Connecticut River) Connecticut, and Rhode Island. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 390-430 mm, tail 22-65 mm, ear 50-60 mm, hindfoot 87-97 mm; weight 0.8-1 kg. The New England Cottontail is a medium-sized species of Sylvilagus . Dorsal fur is pinkish buff to ocher. Back is additionally overlaid with distinct black wash. Ears are short and rounded, and anterior edges are covered with black hair. A characteristic black spot usually occurs between ears. Females are slightly less than 1% larger than males.

Adults have one molt per year in autumn.

Pelage characteristics alone are not sufficient to differentiate the New England Cottontail from the Eastern Cottontail (S. floridanus ); both species can have the same color and pelage characteristics throughout the distribution of the New England Cottontail. Cranial characteristics are most reliable to distinguish the two species.

Habitat. Early successional habitat specialist, inhabiting areas of open woods or their borders, or shrubby areas and thickets in open areas. Historically, New England Cottontails occupied early successional forests that became abundant when farmlands were abandoned, and maturation of these forests into closed-canopy stands caused the decline of this species beginning in the 1960s. New England Cottontails prefers habitats with dense understory vegetation and fallow agricultural lands. They avoid venturing into the open and remain in close proximity to cover.

Food and Feeding. Diet of the New England Cottontail includes a variety of vegetation, but it is the only species of Sylvilagus that extensively consumes conifer needles.

Breeding. Reproductive season of the New England Cottontail lasts from early March to early September, peaking in March—July. It is a postpartum synchronous breeder. Gestation appearsto last 28 days. Litter size averages 3-5 young, and females give birth to an average of 24 young/year. Twenty percent of pregnancies are from juvenile females breeding in their first year. Hybridization between the New England Cottontails and Eastern Cottontails occurs in the wild, but frequency is unknown. A genetic study conducted in the north-eastern USA where both species live sympatrically indicated that no hybridization occurred.

Activity patterns. There is no information available for this species.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Dominance hierarchies of male New England Cottontails regulate access to females and reproductive success. Reproductive behavior is most intense during the estrous period of females, and little social interaction occurs between estrous periods. Reproductive behavior begins 2-3 days before parturition, and postpartum breeding occurs.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The New England Cottontail historically inhabited boreal habitats throughout south-eastern Canada in southern Quebec and north-eastern USA from southern Maine to Connecticut and New York. Nevertheless, a recent study restricted current distribution to 12,180 km?, c.86% less than the historical distribution. It has been hypothesized that the New England Cottontail is a “refugial relict” and that its patchy distribution resulted from a gradual change in climate coupled with invasion and displacement by the Eastern Cottontail in lowland areas. This process appears to be accelerated by habitat alteration. Status of the New England Cottontail has been of concern to biologists and resource agencies for more than four decades. It once had a widespread distribution across New England, USA, but suitable habitats of early successional forest have declined by ¢.86% since 1960, and available habitat has become increasingly fragmented. Moreover, the Eastern Cottontail has invaded much of the habitat of the New England Cottontail. As a consequence, the New England Cottontail has disappeared throughout much of north-eastern USA. It is suspected that the population of the New England Cottontail has been reduced by more than 50% since 1994. They are rare to scarce in fragmented populations. Even in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, which had one of the densest populations in the 1980s, a dramatically decline seems to have occurred based on the last census in 2000-2001. The New England Cottontail is hunted for sport and food. Major threats are competition with the Eastern Cottontail, landscape fragmentation, and forest maturation. An ongoing population decline is expected because threats are unabated. A recent genetic study showed that populations of New England Cottontails in Maine and New Hampshire and on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, are at great risk due to low genetic variability caused by fragmentation that limits gene flow. Problems for conservation of the New England Cottontail are confusion with the Eastern Cottontail by hunters; lack of education on existence, biology, and habitat requirements of the New England Cottontail; and conversion of native shrublands to other land uses. Recommendations are to develop habitat connections among fragmented populations, increase suitable habitat such as early successional and shrub-dominated areas, prohibition of hunting, and recolonize of suitable habitat by translocations. Research on the New England Cottontail should be conducted on biology, ecology, population status, and competition with other lagomorphs.

Bibliography. Barry et al. (2008), Chapman (1975a), Chapman & Ceballos (1990), Chapman & Morgan (1973), Chapman & Stauffer (1981), Chapman et al. (1977), Dalke (1942), Fenderson, Kovach, Litvaitis & Litvaitis (2011), Fenderson, Kovach, Litvaitis, O'Brien et al. (2014), Hall & Kelson (1959), Hoffmann & Smith (2005), Holden & Eabry (1970), Litvaitis, J.A., Barbour et al. (2008), Litvaitis, J.A., Johnson et al. (2003), Litvaitis, J.A., Tash et al. (2006), Litvaitis, M.K., Ruedas et al. (1989), Smith & Litvaitis (2000), Tash & Litvaitis (2007), Tefft & Chapman (1987), Whitaker & Hamilton (1998).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Sylvilagus transitionalis

| Don E. Wilson, Thomas E. Lacher, Jr & Russell A. Mittermeier 2016 |

Lepus transitionalis

| Bangs 1895 |