Sylvilagus audubonii (Baird, 1858)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625539 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625394 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03822308-B74F-FFF0-FFC2-F3EEFD25FD47 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Sylvilagus audubonii |

| status |

|

Desert Cottontail

Sylvilagus audubonii View in CoL

French: Lapin dAudubon / German: Audubon-Baumwollschwanzkaninchen / Spanish: Conejo de desierto

Other common names: Audubon’s Cottontail

Taxonomy. Lepus audubonii Baird, 1858 View in CoL ,

“San Francisco,” San Francisco Co., California, USA.

Genetic analysis showed that S. audubonii and S. nuttallii are sister taxa. As taxonomists are still trying to clarify the species differentiation in Sylvilagus , the subspecific taxonomy is not elaborated yet. The original descriptions of the subspecies are often not very helpful as they are mostly based on few exterior characteristics and small numbers of individuals. It has been shown that the variability is clinal in more careful investigations. Hence, the distinction in subspecies might be arbitrary and unreasonable. Twelve subspecies recognized.

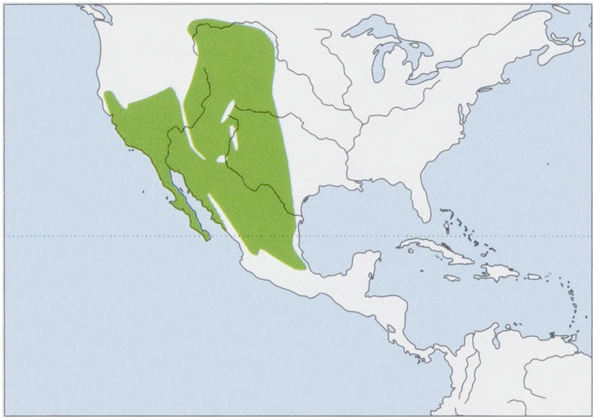

Subspecies and Distribution.

S.a.audubonuiBaird,1858—NCalifornia(WUSA).

S.a.arizonae].A.Allen,1877—SWUtah,SNevada,SECalifornia,W&SArizona(SWUSA),andmostofSonora(NWMexico).

S.a.cedrophilusNelson,1907—EArizonaandWC&CNewMexico(CUSA).

S.a.confinisJ.A.Allen,1898—BajaCaliforniaexcepttheNandBajaCaliforniaSur(NWMexico).

S.a.goldmaniNelson,1904—SSonora,extremeSWChihuahua,extremeWDurango,andSinaloa(WMexico).

S.a.neomexicanusNelson,1907—SWKansas,WOklahoma,N&WTexas,SEtipofColoradoandENewMexico(SCUSA).

S.a.sanctidiegiMiller,1899—SWCalifornia(SWUSA),NWtipofBajaCalifornia(NWMexico).

S.a.vallicolaNelson,1907—CWCalifornia(WUSA).

S. a. warreni Nelson, 1907 — SE Utah, W & S Colorado, NE Arizona, and NW New Mexico (USA). View Figure

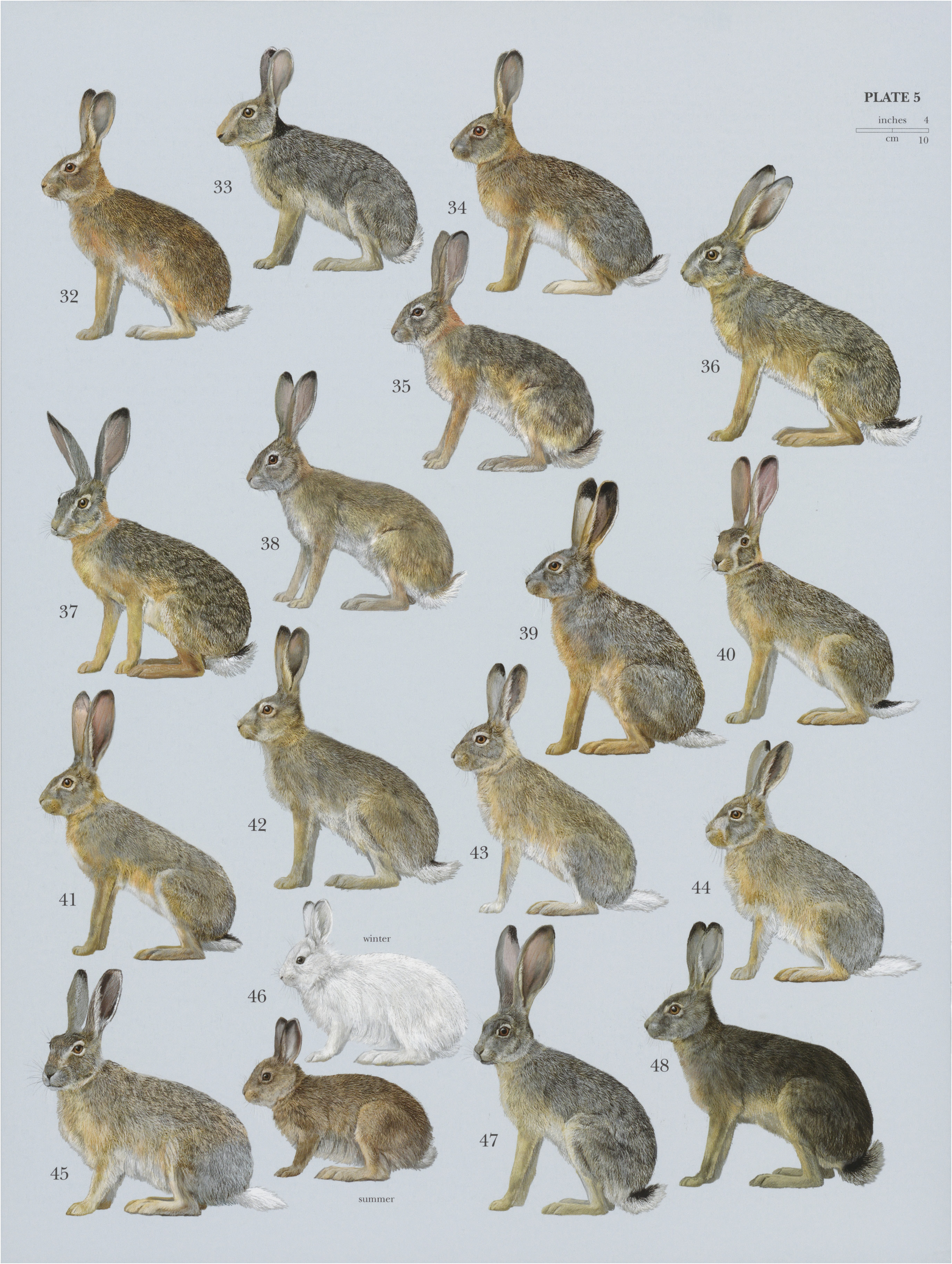

Descriptive notes. Head—body 370-400 mm, tail 39-60 mm, ear 70-80 mm, hindfoot 810-940 mm; weight 511-915 g. The Desert Cottontail is relatively large, with long pointed ears that are sparsely haired on inner surfaces. Pelage is dorsally gray and ventrally white. Hindlegs are long, and feet are slender. Tail is large and dark above and white below. Female Desert Cottontails are ¢.2% larger than males.

Habitat. Arid regions in woodlands, grasslands, and deserts at low elevations throughout the south-western United States. The Desert Cottontail lives from below sea level in Death Valley, California, up to elevations of at least 1829 m. It is often associated with riparian zones in arid regions. In California,its hides are found in heavy brush and willows along rivers. In pine-juniper woodlands, shrubs are its primary cover. Plant species associated with the Desert Cottontail are willows ( Salix sp. , Salicaceae ), buttonwillow ( Cephalanthus occidentalis, Rubiaceae ), wild grape ( Vitis californica, Vitaceae ), greasewood ( Adenostoma fasciculatum, Rosaceae ) in California and arrow-weed ( Pluchea sericea, Asteraceae ), screw-bean mesquite ( Prosopis pubescens) and catclaw ( Acacia greggii), both Fabaceae , in southern Nevada. Occasionally, the Desert Cottontail is found where there is little or no vegetation cover. Abundance of Desert Cottontails is highest under moderate cattle grazing. It relies on thick brambles for cover rather than using holes. The Desert Cottontail in south-eastern Arizona typically builds forms in areas with triangle-leaf bursage ( Ambrosia deltoidea, Asteraceae ) and tall plants (higher than 1-5 m). Desert Cottontails have some physiological adaptations that enable them survive in desert environments. A shift upward of the thermoneutral zone occurs from winter to summer, and basal metabolism decreases by 18% during the same period. Body temperature is 38-3°C when ambient temperatures are below 30°C, whereas body temperature equals ambient temperature of 41-9°C in summer.

Food and Feeding. Diet of Desert Cottontails depends on seasonal availabilities of plants. Food plants include various unidentified grasses; foxtail grass ( Hordeum murinum, Poaceae ); galingale ( Cyperus sp. ) and sedge ( Carex sp. ), both Cyperaceae ; rush ( Juncus sp. , Juncaceae ); willow ( Salix sp. , Salicaceae ); valley oak ( Quercus lobata, Fagaceae ); miner's lettuce ( Montia perfoliata, Montiaceae ); blackberry ( Rubus vitifolius) and California wild rose ( Rosa californica), both Rosaceae ; hoarhound ( Marrubium vulgare, Lamiaceae ); and Baccharis douglasii and California mugwort ( Artemisia vulgaris), both Asteraceae . True grasses ( Poaceae ) such as Johnson grass ( Holcus halepensis), Bermuda grass ( Cynodon dactylon), blue grass ( Poa pratensis), ripgut grass ( Bromus rigidus), and wheat grass ( Agropyron caninum), as well as morning glory ( Convolvulus sp. , Convolvulaceae ), bull mallow ( Malva borealis, Malvaceae ), honeysuckle ( Lonicera sp. , Caprifoliaceae ), and sow thistle ( Sonchus asper, Asteraceae ) were important dietary items of Desert Cottontails in the Sacramento Valley, California. Desert Cottontails living in fields fed almost entirely on grasses. Cultivated hollyhock, carrots, acorns of valley oak, and fruits of almond and peach also are eaten. Type of cover is an important factor to determine feeding sites. Most feeding in late morning and early evening takes place in areas of brushy cover adjacent to open grassland. Important factors that affect daily feeding periods are habitat, season of the year, fog, rain, and wind. Maximum numbers of Desert Cottontails were observed feeding at dawn. Wind appears to interfere greatly with normal feeding. Light intensity determines distance from shelter an individual will venture for food. Desert Cottontails traveled up to 100 m from cover after dark. They feed by taking successive mouthfuls in open situations. Subsequently, heads are elevated, and they start to chew. They extend their bodies along the ground when feeding on low-growing grasses. Necks are stretched out, and front feet edge forward. Hindfeet are brought forward with hops when food can no longer be reached. Generally, terminal parts of plants are eaten.

Breeding. Timing of reproductive season of Desert Cottontails depends on the region. In California, it generally lasts for c¢.7 months in December—June, but one study reported that breeding occurred throughout the year. In Arizona, breeding lasts 8-9 months from January until August or September, whereas in Texas,it starts in late February or early March. Female Desert Cottontails give birth in nests. Five examined nests were pear-shaped excavations, 15-25 cm deep, and 15 cm in diameter near their bottoms. Cavities were first lined with thick layers of fine grass and weeds and then filled with the mothers’ fur. Type of site selected for a nest or burrow varies with habitat. Gestation is ¢.28 days. Neonates have sparse hair. When the nest is touched, young lunge upward and utter a “gupp” sound, which might also be a call used prior to nursing. Females nurse young by crouching over their nests. In one occasion, young were nursed between 13:00 h and 14:00 h after 13-5 hours had elapsed since the previous feeding. Another time, young were nursed at 20:00 h following 30 hours without a feeding. Eyes of Desert Cottontails open c.10 days after birth, and young leave the nest 10-14 days after birth but remain near the nest for up to c.3 weeks. Litter size depends on region and is small for species of Sylvilagus . Meanlitter sizes were 2:9 and 2-7 in Arizona, 2-6 in Texas, and 3-6 in California. In Arizona, females produced an average offive litters per year. Sexual maturity is attained ¢.80 days after birth. The Desert Cottontail appears to be less fecund than some other species of Sylvilagus .

Activity patterns. The Desert Cottontail is most active in early morning and evening and has activity peaks at 05:00-07:00 h and 18:00-20:00 h. They are inactive at temperatures above 27°C. Individuals seek shelter from rain and high winds. The Desert Cottontail use burrows during most of their daily periods of inactivity in open habitat. They hide by sitting in forms that are small cleared places on the ground. Desert Cottontails are more vigilant in late morning and early evening than at dawn or dusk. In California, they remained hidden in thickets during winter days, but they moved about at any time in late spring.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Desert Cottontails choose open patches of ground for running and seldom move in a straight line. They clear tufts of grass and other obstacles in their way with small bounds into the air when running. They swim with rapid strokes by moving their legs alternately. They also climb trees and brush piles. Home range sizes of Desert Cottontails were equal in size to blackberry clumps they inhabited in California. Home ranges of males might be as large as 6-1 ha, whereas those of females might be less than 0-4 ha. Little differences in home range size between males and females were found in another study, with 3-2-3-6 ha for both sexes. Young Desert Cottontails have smaller foraging ranges than adults. Desert Cottontails are not gregarious, but as many as three females might forage together without antagonism. Interactions between males occur; on one occasion, a male chased another male away from a foraging area. Individuals take advantage of alarm calls of other species such as American sparrows (Zonotrichia sp.) or California Ground Squirrels (Otospermophilus beecheyi). Desert Cottontails use their tails as alarm signals. When individuals run for cover, their tails are raised exposing maximum amount of white fur. When individuals are moving about without concern, their tails point toward the ground showing little white. Desert Cottontails adopt rigid postures, called freezing, during times of uncertainty or possible danger. When an individualis truly alarmed, it dashes to the nearest brush. Another alarm signal is thumping with hindfeet. Low prominences such as logs and tree stumps are used to deposit feces. These places are believed to be lookout posts used after dark. Desert Cottontails and jackrabbits ( Lepus sp. ) feed together without animosity.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Desert Cottontail is widespread and common, with a stable population trend. It occurs in a large continuous area and is a habitat and dietary generalist. It is an important game species, and population status is monitored in several states. Cattle grazing and habitat loss due to land clearing might be localized threats, but none of the subspecies are under immediate threat. Predation by invasive species such as feral dogs and feral cats and human-induced fire in some areas inhabited by humans might also be of concern.

Bibliography. AMCELA, Romero & Rangel (2008a), Angermann (2016), Arias-Del Razo et al. (2011), Brown & Krausman (2003), Chapman & Ceballos (1990), Chapman & Morgan (1974), Chapman & Willner (1978), Cushing (1939), Dice (1929), Flinders & Hansen (1975), Grinnell (1937), Halanych & Robinson (1997), Hall (1951, 1981), Hinds (1973), Hoffmann & Smith (2005), Ingles (1941), Kundaeli & Reynolds (1972), Lissovsky (2016), Orr (1940), Sowls (1957), Stout (1970), Sumner (1931).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Sylvilagus audubonii

| Don E. Wilson, Thomas E. Lacher, Jr & Russell A. Mittermeier 2016 |

Lepus audubonii

| Baird 1858 |