Lepus nigricollis, F. Cuvier, 1823

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625539 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625438 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03822308-B751-FFEF-FFC3-F5ADF62CFAE8 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Lepus nigricollis |

| status |

|

Indian Hare

French: Liévre a col noir / German: Schwarznackenhase / Spanish: Liebre de India

Other common names: Black-napped Hare; Indian Desert Hare (dayanus), Rufous-tailed Hare ( ruficaudatus)

Taxonomy. Lepus nigricollis F. Cuvier, 1823 View in CoL ,

“Malabar,” Madras, India.

It has been placed in the genus Caprolagus and subgenus Indolagus, but a study analyzing skull and dental characteristics suggests that Caprolagus is synonymous to Lepus . This species needs taxonomic clarification. It includes ruficaudatus and dayanus as subspecies; ruficaudatus might be closer to L. capensis , whereas dayanus might deserve species status. It may include L. victoriae whytei, L. crawshayi (currently a synonym of L. victoriae ), and L. peguensis as subspecies. As taxonomists arestill trying to clarify the species differentiation in Lepus , the subspecific taxonomy is not elaborated yet. The original descriptions of the subspecies are often not very helpful as they are mostly based on few exterior characteristics and small numbers of individuals. It has been shown that the variability is clinal in more careful investigations. Hence, the distinction in subspecies might be arbitrary and unreasonable. Seven subspecies recognized.

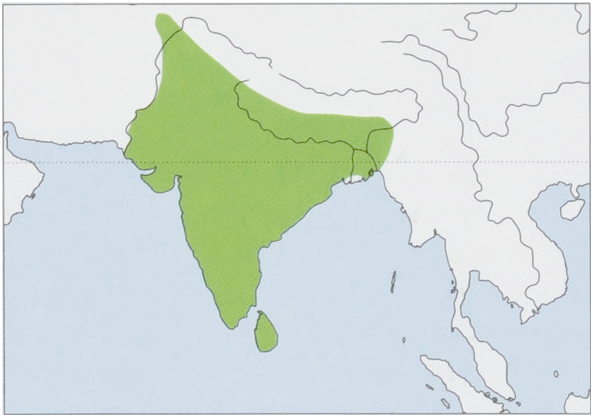

Subspecies and Distribution.

L.n.nigricollisF.Cuvier,1823—SIndia(SoftheGodavariRiver).

L.n.aryabertensisHodgson,1844—SCNepal.

L.n.dayanusBlanford,1874—SEPakistanandNWIndia(GreatIndianDesert).

L.n.sadiyaKloss,1918—NEIndia(Assam).

L.n.simcoxiWroughton,1912—CIndia(NMaharashtraandMadhyaPradesh).

L. n. singhala Wroughton, 1915 — Sri Lanka.

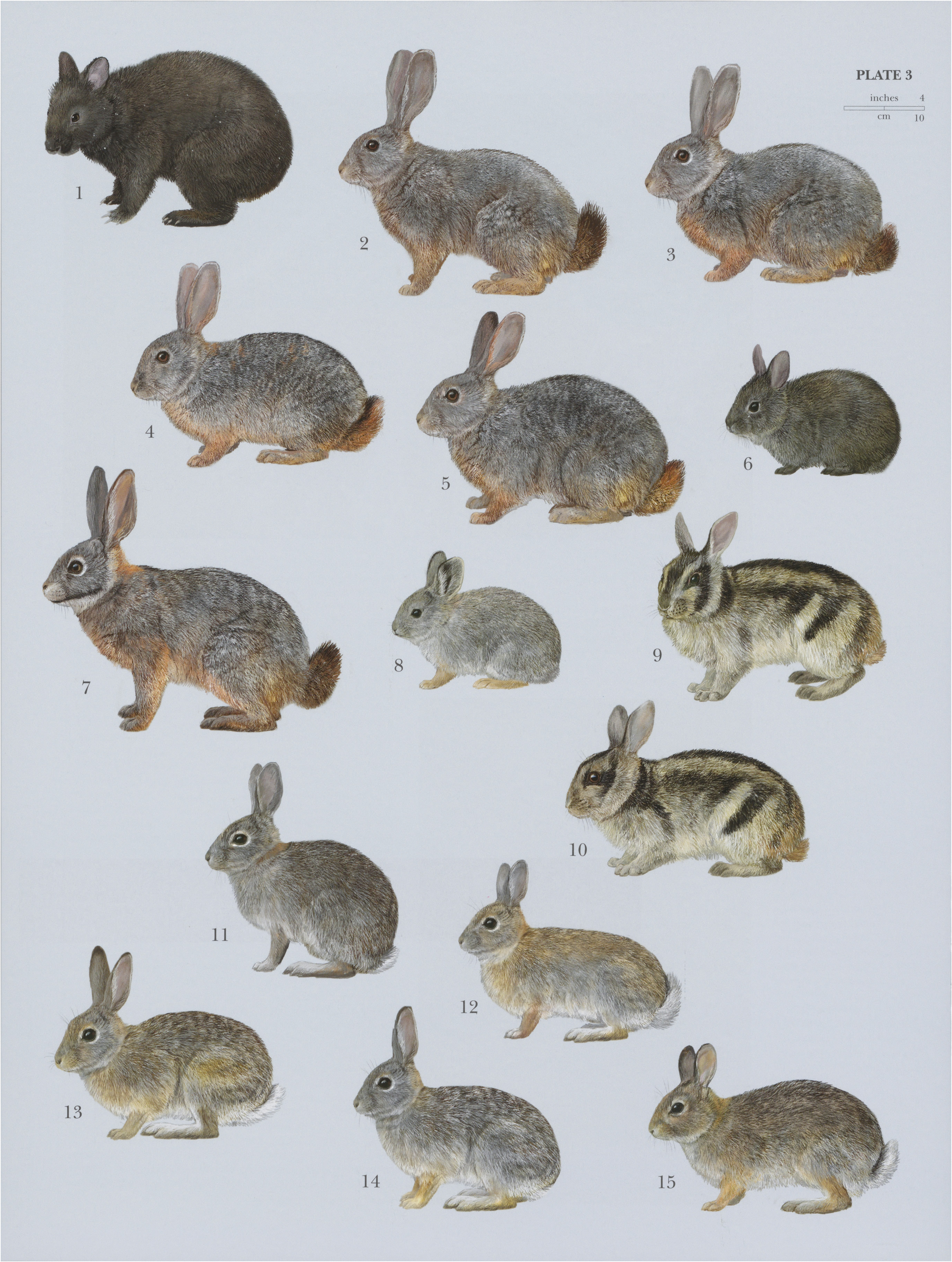

Indian hares (probably ruficaudatus) also occur in extreme E Afghanistan, in the border areas with Pakistan. Situation in Java is debated and the so called “Javan Hare” might be native there. The species has been introduced by founder individuals of either unknown subspeciesaffiliation or belonging to various subspecies into Comoro, Mayotte, Madagascar, Réunion (including Gunners Quoin I), Mauritius (Agaléga Is), Seychelles (Cousin I), and Andaman Is in the Indian Ocean, and into New Guinea. In Gunners Quoin the Indian Hare has been eradicated. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 330-530 mm, tail 10-90 mm, ear 100-120 mm, hindfoot 89-103 mm; weight 1.8-3.6 kg. The Indian Hare is medium-sized. Dorsal fur and head are rufous-brown, mixed with black. Legs and chest are rufous; ventral fur and chin are white. The Indian Hare is larger toward the southern part of its distribution. Color varies in different subspecies— nigricollis has a dark brown or black patch on neck and its tail is black above, ruficaudatus has a gray neck patch and upper side of its tail is brown, dayanuslives in the desert and has a pale yellow-sandy color. A female ruficaudatus (average 2-2 kg) is heavier than a male (1-8 kg).

Habitat. Open desert with scattered shrubs, thick jungle with some open clearings, grasslands, and large tracts of scrub and wasteland, alternating with cultivated plains, at elevations of 50-4500 m. Indian Hares spent the day in short grasslandshrub forest areas in Nepal and under bushes in the Sindh Desert, borderlands of Pakistan and India. Tall shrubs (e.g. Zizyphus, Rhamnaceae ) or young palms are used as forms. The Indian Hare might use ditches or animal burrows for cover when pursued.

Food and Feeding. Diet of the Indian Hares includes mainly grass and forbs. They feed on Capparis deciduas ( Capparaceae ), blue panicgrass ( Panicum antidotale, Poaceae ), rattlepods ( Crotalaria spp. , Fabaceae ), and Zizyphus spp. in the Sindh Desert. Their diets contain up to 77% grasses in wetter regions. Indian Hares might travel 100-500 m to reach green vegetation in the dry season. They eat grass, young plants, leaves of the sweet potato plant, and lettuce from gardens in Sri Lanka. Analysis of feces of Indian Hares on Cousin Island showed that sedges and grasses are mainly consumed in one area, but prickly chaff flower ( Achyranthes aspera, Amaranthaceae ) and Ficus reflexa ( Moraceae ) dominated the diet in another area. Indian Hares can damage young trees and agricultural crops such as chickpeas ( Cicer arietinum, Fabaceae ) and peanuts ( Arachis hypogaea, Fabaceae ) in Pakistan. They fed on short grass and crops in western Nepal.

Breeding. NearJodhpur, India, Indian Hares are reproductively active throughout the year, with a peak during the monsoon (July-September). Average annual litter size was 1-8 young (range 1-4). Litter sizes varied throughout the year, with one young in winter to 3-2 young in July.

Activity patterns. Indian Hares are crepuscular and nocturnal, but at high densities on Cousin Island, they became active and started to feed in mid-afternoon. They spend the day in a series of forms used for shelter. A single individual might use different forms in the morning and afternoon, depending on the weather.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home range sizes are 1-10 ha in Nepal and 0-7-1-8 ha on Cousin Island. Larger home ranges are expected in more open country and desert.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Indian Hare is listed under the Schedule IV of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972. It is widespread and abundant. It is shot as game and snared or netted by farmers to prevent crop damage. Populations in India are severely fragmented due to expanding agricultural areas and pressure on forests from collection of fuel wood. Major threats to Indian Hares are habitat destruction, conversion of prime forest areas to agricultural areas, and intensive hunting. Other threats are feral and domestic predators, competition from livestock, and human-caused forest fires. The uncertain taxonomic status of the Indian Hare makes conservation activities difficult. For example, the Javan Hare might be an endemic taxon based on its long fossil history, which would merit urgent actions because ofits very low population size.

Bibliography. Angermann (1983, 2016), Bell (2002), Brooks et al. (1987), Chakraborty, Srinivasulu et al. (2005), Ellerman & Morrison-Scott (1951), Flux & Angermann (1990), Ghose (1971), Hoffmann & Smith (2005), Jain & Prakash (1976), Kirk (1981), Kirk & Bathe (1994), Kirk & Racey (1992), Lissovsky (2016), Long (2003), Maheswaran & Jordan (2008), McNeely (1981), Petter (1961), Phillips (1935), Prakash & Taneja (1969), Prater (1971), Purohit (1967), Sabnis (1981), Srinivasulu & Srinivasulu (2012), Suchentrunk (2004), Suchentrunk & Davidovic (2004).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.