Oryctolagus cuniculus (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625539 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6628185 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03822308-B754-FFED-FF6D-F725F820F363 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Oryctolagus cuniculus |

| status |

|

European Rabbit

Oryctolagus cuniculus View in CoL

French: Lapin de garenne / German: Wildkaninchen / Spanish: Conejo europeo

Other common names: Domestic Rabbit, Wild Rabbit

Taxonomy. Lepus cuniculus Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

“in Europa australis.” Restricted by J. R. Ellerman and T. C. S. Morrison-Scott in 1951 to “Germany.”

The genus Oryctolagus is monotypic; however, subspecies algirus has exceptional high nucleotide diversity compared with European Rabbit populations on the Iberian Peninsula and worldwide. Furthermore, it has distinct morphological, genetic, reproductive, and parasitological characteristics, and therefore, elevation to species status is under consideration. As in the other Leporidae species, the subspecific taxonomy is not elaborated yet. The original descriptions of the subspecies are often not very helpful as they are mostly based on few exterior characteristics and small numbers of individuals. It has been shown that the variability is clinal in more careful investigations. Hence, the distinction in subspecies might be arbitrary and unreasonable. Six subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

O. c. cuniculusLinnaeus, 1758 — N, NE & EIberianPeninsula (Spain).

O. c. brachyotusTrouessart, 1917 — SFrance.

O. c. cnossiusBate, 1906 — CreteI.

O. c. habetensisCabrera, 1923 — Tanger-Tetouan-AlHoceimaRegion (NMorocco).

O. c. huxleyi Haeckel, 1874 — Mediterranean Is (Balearic Is, Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily and Macaronesia (Azores, Madeira, and Canary Is).

Original distribution after last Ice Age restricted to Iberian Peninsula, W France, and N Africa. Ancient introductions of the nominate subspecies probably during the Roman period have spread it throughout Europe, and now it is present in most of W, C & E Europe and the Mediterranean and Macaronesian Is (these mostly old introductions are also shaded on the map). During the 20" century it has been released into the steppes of the Black Sea in Ukraine and Russia (N Caucasus); introduced into Australia in 1788 and again in 1859 where it is now widespread;it is found on many Pacific Is, islands off the coast of South Africa and Namibia, and in New Zealand; successfully introduced only since 1936 into South America, nowadays with a limited range in Chile, Argentina, and Falkland Is, it is also present in the Caribbean Is (all these modern introductions not shaded in the map). Worldwide as domesticated forms.

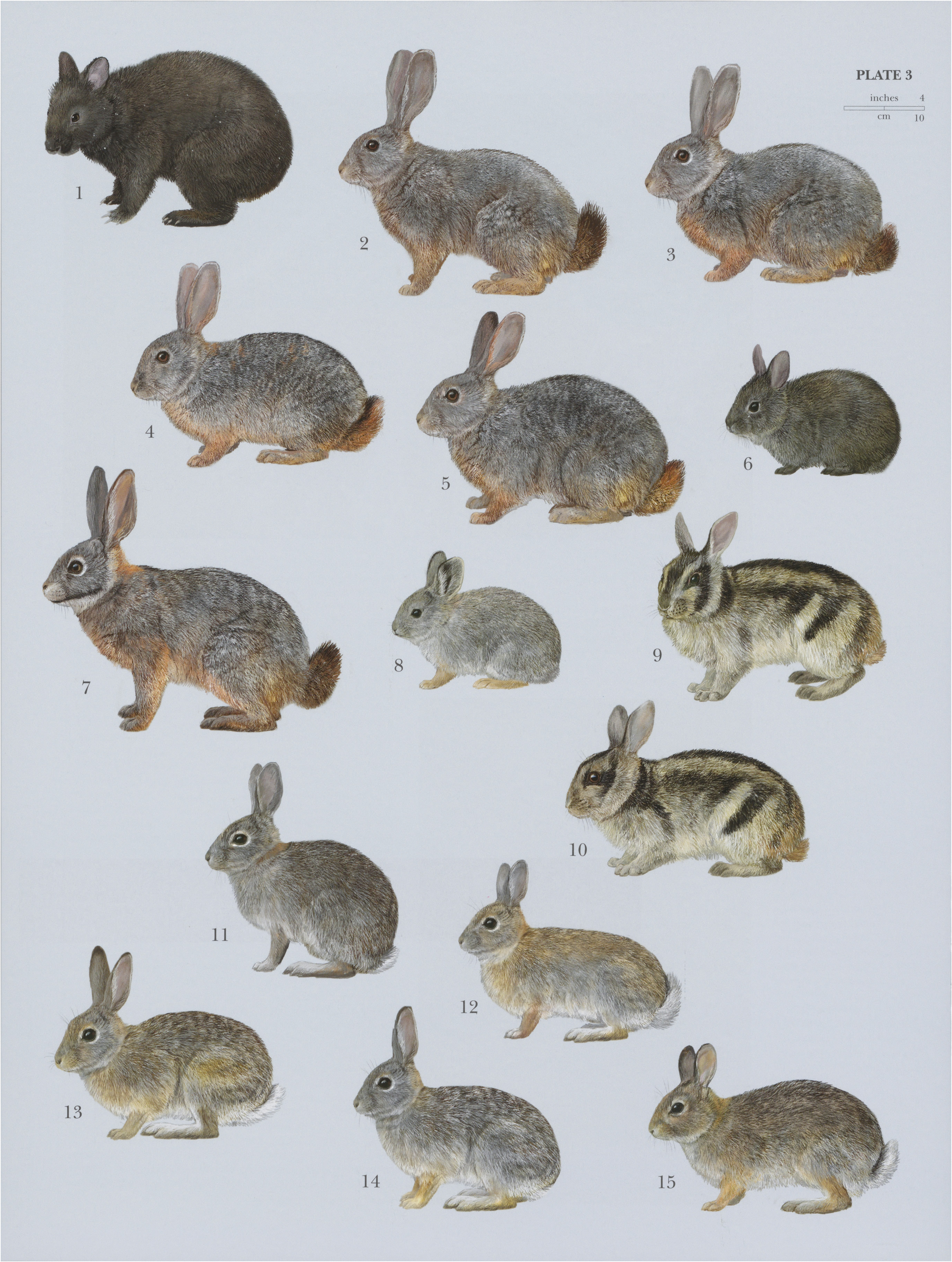

Descriptive notes. Head-body 360-380 mm, tail 65-70 mm, ear 70-80 mm, hindfoot 80-89 mm; weight 1.5-3 kg. The European Rabbit is small and has grayish brown fur. Dorsal fur and head are pale brown and slightly flecked with black and buff. Ventral pelage is white, with pale ginger-buff. Chin and throat are white. Ears are short, dark brown, and without black tips. Nuchal patch is pale rufous brown, and throat patch is ginger-buff with orange. Forelimbs and hindlimbs are short and pale brown. Hindfeet are white above. Tail is short and the same color as dorsal fur above;laterally it is brown or white and below it is white. Pelage color varies geographically. Domestic rabbits and feral descendants of the European Rabbit vary in color from white to brown and black, with or without different colored patches.

Habitat. Ideally, habitats with a Mediterranean climate and less than ¢.1000 mm of rain/year, short herbage, dry and loosely compacted soils that can be easily dug, or with secure refuge areas in thickets near open feeding grounds, below elevations of ¢.1500 m. Nevertheless, European Rabbits also inhabit cold and wet habitat and high mountains, dense bushy regions, and arid habitats in Morocco. They tend to avoid forested habitats and open areas in Algeria.

Food and Feeding. Diet of European Rabbits consists of grasses and forbs, mostly the former, and differ considerably between habitats and season.

Breeding. The European Rabbit breeds opportunistically in any season, making it an ideal colonist. Breeding begins and ends earlier in the year the lower the latitude in its introduced distribution. Length of reproduction season and number oflitters produced each year depend on length of growing season of plants in the diet. Thus, reproductive season lasts for c.4 months/year at higher latitudes to at least ¢.9 months/year in temperate New Zealand, where it was introduced. Winter breeding of European Rabbits in Mediterranean climates ceases in late spring. In more temperate climates, breeding begins in early spring and continues through mid-summer. In semiarid regions of Australia where droughts last many months, with occasional heavy rains to which the vegetation responds vigorously, opportunistic breeding of European Rabbits is most distinct. Gestation lasts 28-30 days. During early gestation, a female can terminate a pregnancy or reduce litter size by resorbing single embryos or whole litters if conditions are unfavorable for lactation—the most demanding stage of reproduction. Litter sizes are 3-9 young, depending on season and environmental conditions. Mean litter sizes are 4-6 young in mid-season and 3-4 young during off-peak periods. Seasonal and regional variation in litter size is less pronounced than length of the breeding season. Consequently, annual number of young per female depends primarily on length of the breading season. Number of young European Rabbits born per female per year is 15-45 and depends on climate. Females have postpartum estrus or a seven-day estrous period. Young are born in a nest of dead vegetation lined with fur from their mother’s belly. Nest is placed either in a short sub-branch of an existing burrow or a separate breeding burrow called “stop” c¢.1 m long. The female closes the stop with soil when she leaves. Breeding burrows of European Rabbits may be made days, weeks, or even months before they are used; some are never used. A study conducted in Australia showed that the dominant female breeds in the warren, and subordinate females breed in isolated stops. When brush coveris sufficient, European Rabbits often live permanently aboveground and have no warrens;all breeding takes place in stops. Young are altricial and born naked with closed eyes. A female feeds her young once a night for only c¢.5 minutes. They are weaned at ¢.20 days old, after which they leave the nest. Maturity is reached at 3-4 months old. Population numbers often fluctuate greatly.

Activity patterns. The European Rabbit is nocturnal but active at dawn and dusk. Daily activity aboveground depended on density relative to food supply. If density was high and food was limited, more than 60% of an introduced population in New Zealand was aboveground during the day. Moreover, individuals in the New Zealand population emerged earlier, relative to sunset, in winter and spring than summer and autumn. Individuals remained in their daytime resting places from soon after dawn until at least mid-afternoon. During the breeding season, females often began to feed soon after midday.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The European Rabbit digs extensive underground burrows (“warrens”) for resting during the day and protection when threatened. It sometimes lives permanently aboveground, lying in dense vegetation during the day and using burrows only for breeding. It is territorial and forms social groups with a strict linear hierarchy of dominance. A dominant male lives in a warren with several females and their young. Isolated pairs, small groups of three animals, or even solitary individuals are common at low densities. Neighboring groups of European Rabbits may feed together at night. Defended territories are usually small (often less than 1 ha). When food is short or clumped, European Rabbits might feed communally at night at distances of at least 500 m away from their resting areas. Nightly home ranges are much larger than daily home ranges. Males have larger home ranges than females. Adults rarely shift their home range permanently. A minority ofjuveniles disperses several kilometers from where they were born but most stay in their natal home ranges. When the European Rabbit was introduced in Australia, it spread into unoccupied areas at rates of up to 300 km/year.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List. The European Rabbit is a widespread colonizer and considered a pest outside its natural distribution where its eradication is priority for conservation; however, only those within the natural distribution in Spain, Portugal, and north-western Africa are considered in [UCN’s assessment. The European Rabbit's original distribution after the last ice age included only the Iberian Peninsula, western France, Morocco, and Algeria. Currently, it inhabits most of Western and Central Europe (from Ireland, north to Denmark and southern Sweden, east to Ukraine and Romania, and south to Croatia and Italy), and it also occurs on most Mediterranean islands (Balearic, Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, Cyprus, and many Greek islands). The domesticated form of the European Rabbit occurs worldwide. Populations of European Rabbits have declined ¢.80% in Spain since 1975. In 2005, a study in the Donana National Park revealed that the remaining population was aslittle as 5% of the population size in 1950. A study in Portugal recorded a population reduction of 24% from1995 to 2002. Causes for declines are disease, habitat loss, and human-induced mortality. Decline of the European Rabbit is uneven across its distribution due to varying degrees of threat. Two diseases that appeared in the 20" century are major threats to European Rabbits. Myxomatosis is a virus from South America spread by insects (mosquitoes and fleas) that was intentionally introduced by a famer in the mid-1950s to control the rabbit population in France. An estimated 90% of European Rabbits has perished due to myxomatosis since the 1950s. Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease is a virus spread by direct contact. The virus appeared in Europe in the late 1980s and initially caused death of 55-75% of European Rabbits on the Iberian Peninsula. Death typically occurred within 24 hours of symptom onset, with a short incubation time ofless than 48 hours. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to modern intensive agriculture, high-intensity livestock production, fallow land that returns to closed forest, tree plantations, urbanization, increased fire danger, and climate change are ongoing threats to European Rabbits. Furthermore, hunting is a threat in some areas. Future threats to the European Rabbit may include a genetically modified version of the myxomatosis virus that is being developed in Australia to suppress recruitment where European Rabbits have been introduced. Unlicensed release of the modified virus into the native distribution could devastate remaining populations. Conservation for the European Rabbit was delayed for several decades after their decline became apparent. Efforts began to take shape in the late 1980s due to previous political isolation of its native distribution and lack of information on the European Rabbit as keystone species in Iberian ecosystems. The issue of eradication of the European Rabbit from introduced areas (e.g. Australia, New Zealand, and many islands) may have overshadowed decline in its native distribution. Increased interest in specialist predators such as the Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus) and the Spanish imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti) that depend on European Rabbits and sustainability of hunting populations have enhanced public discussion. The European Rabbit occurs in some protected areas within its natural distribution, including Donana National Park in Spain and Serra da Malcata Nature Reserve in Portugal where the Iberian Lynx is protected. Itis a keystone species in the Iberian ecosystem, as prey for specialist predators and as a landscape “modeler” that maintains vegetation growth typical to Spain and Portugal, creates habitat for invertebrate species, increases species richness, and increases soil fertility.

Bibliography. Alves & Ferreira (2002), Angermann (2016), Angulo & Cooke (2002), Aulagnier & Thévenot (1986), Beaucournu (1980), Bell & Webb (1991), Biju-Duval et al. (1991), Brambell (1944), Branco et al. (2000), Carneiro, Albert et al. (2014), Carneiro, Ferrand & Nachman (2009), Delibes & Hiraldo (1981), Delibes et al. (2000), Ellerman & Morrison-Scott (1951), Fa et al. (1999), Ferrand (2008), Ferreira et al. (2015), Flux (1994), Flux & Fullagar (1992), Flux et al. (1990), Fraser (1985), Gibb (1990), Gibb & Williams (1994), Gibb et al. (1985), Goncalves et al. (2002), Happold (2013c), Hoffmann & Smith (2005), Kaetzke et al. (2003), Kowalski & Rzebik-Kowalska (1991), Lever (1985), Lissovsky (2016), Mitchell-Jones et al. (1999), Myers et al. (1994), Mykytowycz & Gambale (1965), Rogers et al. (1994), Smith & Boyer (2008f), Smithers (1983), Villafuerte et al. (1995), Virgos et al. (2005), Ward (2005), Willott et al. (2000), Wood (1980).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Oryctolagus cuniculus

| Don E. Wilson, Thomas E. Lacher, Jr & Russell A. Mittermeier 2016 |

Lepus cuniculus

| Linnaeus 1758 |