Lepus californicus, Gray, 1837

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625539 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625462 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03822308-B75B-FFE4-FAF7-F8FAF583FCEB |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Lepus californicus |

| status |

|

Black-tailed Jackrabbit

Lepus californicus View in CoL

French: Lievre de Californie / German: Eselhase / Spanish: Liebre de cola negra

Other common names: California Jackrabbit

Taxonomy. Lepus californicus Gray, 1837 View in CoL ,

“St. Antoine [probably near Mission of San Antonio, California, USA].”

Lepus insularis is an insular melanistic allospecies and closely related to L. californicus . It is still under debate whether or not L. insularis deserves species status or represents an isolated population of L. californicus . In southern Arizona, L. californicus and L. alleni live in sympatry. As taxonomists are still trying to clarify the species differentiation in Lepus , the subspecific taxonomy is not elaborated yet. The original descriptions of the subspecies are often not very helpful as they are mostly based on few exterior characteristics and small numbers of individuals. It has been shown that the variability is clinal in more careful investigations. Hence, the distinction in subspecies might be arbitrary and unreasonable. Seventeen subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

L. c. californicus Gray, 1837 — SW Oregon, and NW California (W USA).

L. c. altamirae Nelson, 1904 — SE Tamaulipas (NE Mexico).

L. c. asellus Miller, 1899 — SE Coahuila, NE, S Nuevo Leon, E & SE Zacatecas, San Luis Potosi, Aguascalientes, NE tip ofJalisco, N Guanajuato, and NW Querétaro (NC Mexico).

L. c. bennettiz Gray, 1843 — SW California (SW USA), and NW Baja California (NW Mexico).

L. c. curts Hall, 1951 — Is along the coast of Tamaulipas (NE Mexico).

L. c. deserticola Mearns, 1896 — SE Oregon, S Idaho, SW Montana, NE & E California, Nevada, Utah except SE, and NW, W & SW Arizona (W & SW USA), and NW Sonora and NE Baja California (NW Mexico). The population in SW Montanais isolated.

L. c. eremicus J. A. Allen, 1894 — S Arizona (SW USA), N Sonora except extreme NW, NW Chihuahua (N Mexico).

L. c. festinus Nelson, 1904 — S Querétaro, Hidalgo, and N State of Mexico (C Mexico).

L. c. magdalenae Nelson, 1907 — Magdalena I, Baja California Sur (NW Mexico).

L. c. martirensis Stowell, 1895 —Baja California except NW & NE and NE Baja California Sur (NW Mexico).

L. c. melanotis Mearns, 1890 — S South Dakota, SE Wyoming, Nebraska, E Colorado, Kansas, W Missouri, NE New Mexico, Oklahoma, W Arkansas, and N Texas (C USA). An isolated population exists in E Oklahoma.

L. c. merriami Mearns, 1896 — S Texas (S USA), and NE Coahuila, N Tamaulipas, and N Nuevo Leon (NE Mexico).

L. c. richardsonii Bachman, 1839 — C California (SW USA).

L. c. sheldoni Burt, 1933 — Isla del Carmen, Baja California Sur (NW Mexico).

L. c. texianus Waterhouse, 1848 — SE Utah, SW Colorado, NE Arizona, New Mexico except the NE, and W Texas (C USA), Chihuahua except the NW, W, & SW extremes, W Coahuila, E Durango, and NW Zacatecas (NC Mexico).

L. c. wallawalla Merriam, 1904 — S Washington, C & W Oregon, NE California, and NW Nevada (NW USA).

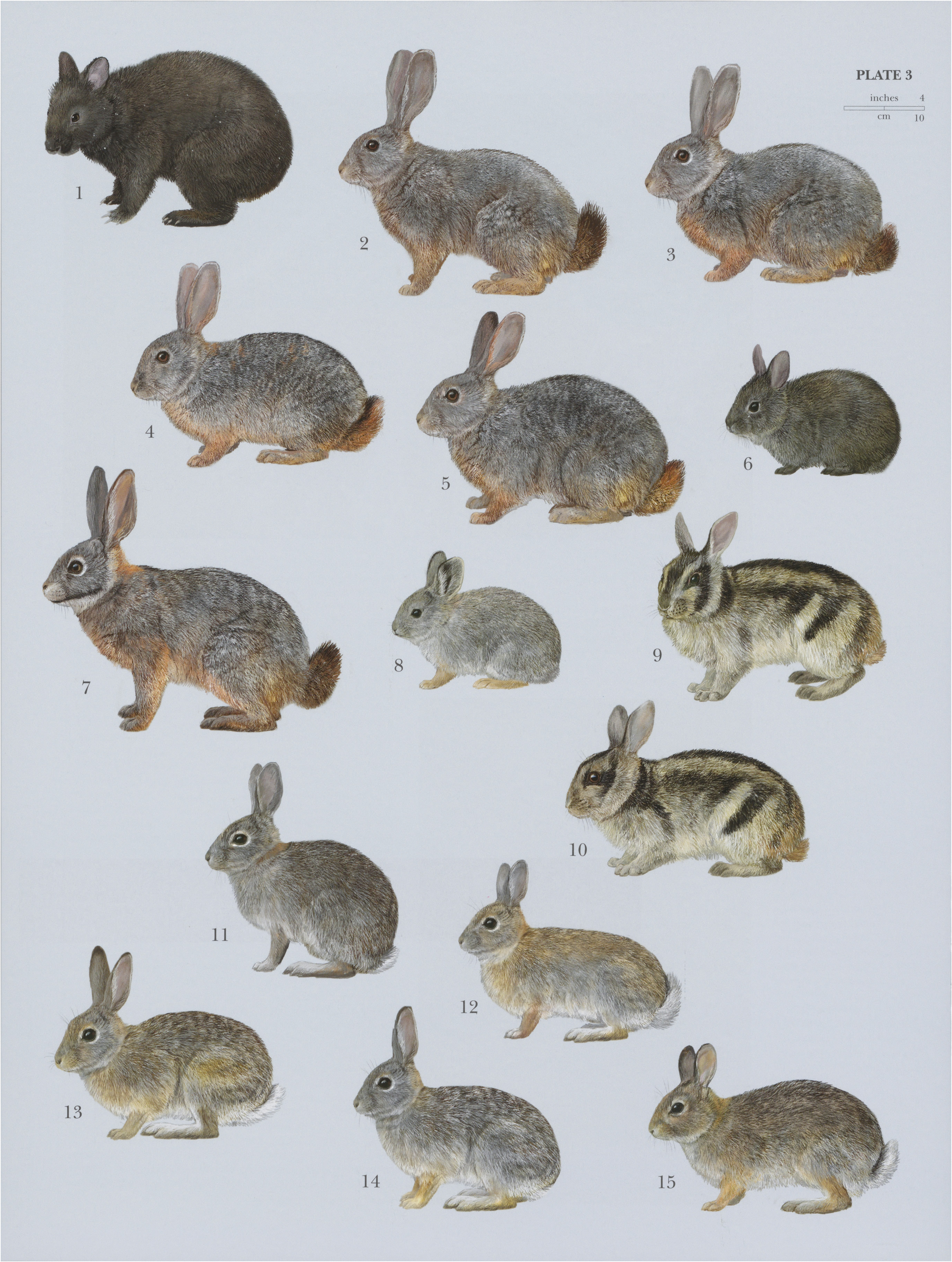

L. ¢. xanti Thomas, 1898 — Baja California Sur except the NE (NW Mexico). View Figure

The Black-tailed Jackrabbit has been introduced into Massachusetts, NewJersey, Maryland, Virginia, and S Florida.

Descriptive notes. Head—body 520-610 mm, tail 75-101 mm, ear 100-130 mm, hindfoot 113-135 mm; weight 1.5-3.6 kg. The Black-tailed Jackrabbitis lean and mediumsized, with soft fur. Dorsal pelage is brownish to grizzled brown, sides are brownish, and ventral fur is pale. Hindlegs and ears are relatively long, and tail is large, with black stripe above and buffy or grayish below. Color varies considerably among populations. Differences in color and other characteristics relate to corresponding changes in climate; soil color might influence fur color. On the Guadiana lava filed in Durango, Mexico, fur is browner than on those individuals from northern Durango. In Kansas (USA), sexual dimorphism in mass and length has been noted; females are larger than males. Body size of the Black-tailed Jackrabbit is larger on islands around Baja California, except the population on Carmen Island that is smaller than adjacent populations. Annual molt begins between late August and early October, depending on latitude, and short summer hair is replaced by longer winter hair. Ear lengths of Black-tailed Jackrabbits vary geographically with temperature. Ears are longer in the south than in the north; longer ears are probably used to dissipate heat. Rectal glands in males and females secrete strong musky odors, but their functions are unknown. No physical change is noticeable during the breeding period; even mammae remain flat in lactating females.

Habitat. Arid tropics, deserts, and transitional habitats at elevations of -84 m in Death Valley, California, USA, to 3750 m. Black-tailed Jackrabbits favor heavily grazed areas, or where grasses are not abundant and cacti and low shrubs are scattered. They inhabit open habitats with mesquite ( Prosopis ), sagebrush ( Artemisia ), desert scrub, and open pine ( Pinus )—juniper ( Juniperus ) in Arizona. They avoid areas of tall grass or forest where visibility is obscured. Where Black-tailed Jackrabbits and Antelope Jackrabbits ( L. alleni ) live in sympatry, they are often seen togethersitting under the same bush or running away side by side. Antelope Jackrabbits are more numerous on grassy plains at high elevations, and Black-tailed Jackrabbits are more numerous in mesquite along valley bottoms and in barren chaparral desert.

Food and Feeding. Diet of the Black-tailed Jackrabbit varies among locations and seasons, but grasses and sedges are primarily eaten in summer. In Utah,it ate nearly all plant species available, including sagebrush ( Artemisia tridentata, Asteraceae ) and shadscale ( Atriplex confertifolia), Nuttall’s saltbush (A. nuttalliz), winterfat (Ewrotia lanata), and saltlover ( Halogeton glomeratus) all Amaranthaceae . The Black-tailed Jackrabbit also eats fungi, gravel, or sand, and it has been reported to feed on horse carcasses in Texas and Tamaulipas. During winter or in desert areas, the main food is dry and woody plant parts such as broom snakeweed ( Gutierrezia sarothrae, Asteraceae ) and creosote bush ( Larrea tridentate, Zygophyllaceae ). There is no evidence that the Blacktailed Jackrabbit drinks free water. In dry habitats, succulent plants and cacti are increasingly eaten as drought conditions increase. Shade seeking reduces heat load and need for water. Other factors that contribute to reducing water loss are insulation and reflectivity of pelage. The Black-tailed Jackrabbit can damage agricultural crops. In Kansas (USA), most crop damage was restricted to fields near resting areas, and buffer fields reduced damage. While feeding, Black-tailed Jackrabbits move slowly and are constantly alert for sings of danger. They rely on hearing more than on other sense to detect danger. Black-tailed Jackrabbits rear up on their hindfeet to browse on bushes.

Breeding. Reproductive season of the Black-tailed Jackrabbit depends on latitude. In California, males are sexually active in all months of the year, but in Kansas, they are active in December—August. Breeding season is shortest in regions with severe winters (e.g. 128 days in Idaho) and longest in areas with warmer winters (e.g. 220 days in Kansas and more than 300 days in Arizona). A sexually active male Black-tailed Jackrabbit seeks a female with his nose close to the ground. Courtship behavior includes circling, hunting, approaching, chasing, jumping with urine emission, and boxing; copulation usually follows. These complex sequences of behavior may be repeated a couple of times. Breeding is promiscuous. Copulation occurs repeatedly, which induces ovulation. Gestation is c.43 days.Litter size is positively correlated with latitude and averages c.2 young in Arizona, c.3 young in Kansas and Nevada, and c.5 young in Idaho and California. Maximum number of young per litter is seven in California, Idaho, and Nevada. Litter size is dependent on environmental conditions during a particular year, quantity of precipitation, and time of the year; largest litters occur in the middle or end of the breeding period. There are 3-8—4-4 litters/year in Kansas and 3-6 litters/ year in Arizona. Postpartum estrus occurs, but consistent postpartum breeding does not occur in Kansas. Young are placed put in prepared nests with some hair for lining or in nests resembling shelters under bushes when soil is hard. Young are fully furred, and eyes are open at birth. Pelage of young is brown and richer in color than mothers’ pelage. Ear tips and tail are black. Dark natal fur gradually is replaced by paler immature pelage. Adult pelage occurs in the first winter when young are 6-9 months old. Young are nursed exclusively for their first ten days of life, and solid food is gradually eaten; they are weaned at 12-13 weeks of age. Until young are c.1 week old, they suckle lying on their backs, with their hindfeet around their mothers’ necks; then, nursing position changes to an upright posture. Newborns stay close to their birthplace for their first two days oflife; they gradually enlarge their home ranges and spend a lot of time digging. Females stay some distance away and moveto their litters only at night to nurse. Early-born females might breed in their first year of birth.

Activity patterns. The Black-tailed Jackrabbit is primarily nocturnal, with activity peaks at 04:00-07:00 h and 18:00-20:00 h. Feeding periods vary greatly with weather, season, and moon phase. Wind is the most important weather factor limiting activity. Calm and dry evenings are more favorable for longer feeding periods than windy and wet evenings. Falling snow and fog limit nocturnal activities, but rain and temperature have little effect on movement. The Black-tailed Jackrabbit often builds forms to protect itself from heat during the day by making excavations in sand under vegetation. In the Mojave Desert, USA, the Black-tailed Jackrabbit retreats to burrows during hot summer days but only for 3-5 hours in the afternoon. Self-constructed burrows begin as forms and gradually are deepened by digging during hot afternoons. After several days, burrows are deep enough to enclose an individual. Some Black-tailed Jackrabbits also use holes dug by prairie dogs (Cynomys) or American Badgers (Taxidea taxus). Burrows are not used during high winds or cold weather, even though they are typically available.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Black-tailed Jackrabbits do not usually migrate, but one population in Utah migrates to and from traditional wintering areas. There are noticeable changes in numbers of Black-tailed Jackrabbits throughout the year that might be caused by movements to areas with more food or favorable temperatures. Daily movements vary depending on distances between resting and feeding areas. These distances might be short or as long as 16 km. The Black-tailed Jackrabbit makes conspicuous trails and runaways through brush, weeds, meadows, and fields and over dusty or sandy surfaces of desert valleys. Home range sizes are 20-140 ha, and females have larger home ranges than males. In Kansas, home ranges ofjuveniles (4-28 ha, mean 14 ha) were smaller than adults (5-78 ha, mean 17 ha). In Idaho, similar home range sizes were recorded, and c.18% of the population disperses over large distances. Black-tailed Jackrabbits avoid entering water, but they will move across rivers at ice jams or forage on vegetation in 5 cm of water. Black-tailed Jackrabbits are not gregarious; however, groups of 2-5 individuals occur during the breeding season, and groups as large as 200-250 individuals aggregate to feed in winter. There is no social organization among individuals at the same feeding ground. Normally, individuals close together ignore each other, but they might butt, bite, jump into the air, run in circles at high speed around each other, or simply avoid each other. Females often attack other individuals that approach within 5-10 m. This antagonism leads to spacing and might be a type of territorial behavior. The only family structure exists between mother and young as long as nursing occurs. Male Black-tailed Jackrabbits frequently fight by rearing up on their hindlegs and striking each other with their forefeet. Biting, especially on the ears, also occurs. Females sometimes react aggressively to approaching males with low growls or grunts.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Blacktailed Jackrabbit is widespread, and its distribution is expanding. Because the Blacktailed Jackrabbit adapts well to overgrazed areas, it seems to expand at the expense of the White-tailed Jackrabbit (L. townsendii) in the north-east and the White-sided Jackrabbit ( L. callotis ) and Antelope Jackrabbit in the south of its distribution. Major threats are hunting for sport and local subsistence, human perturbation, predation by introduced species, competition with livestock, habitat fragmentation, and humaninduced fires. Research is needed to definitively classify subspecies and on interactions among Black-tailed Jackrabbits and other sympatric jackrabbits (i.e. White-tailed Jackrabbit, White-sided Jackrabbit, and Antelope Jackrabbit).

Bibliography. AMCELA, Romero & Rangel (2008g), Angermann (2016), Arias-Del Razo et al. (2011), Bailey (1936), Baker (1956, 1960), Bednarz & Cook (1984), Best (1996), Blackburn (1973), Bronson & Tiemeier (1958a, 1958b), Burt (1934), Cahalane (1939), Corbet (1983), Costa et al. (1976), Couch (1928), Currie & Goodwin (1966), Desmond (2004), Dice (1926), Dickerson (1917), Dixon et al. (1983), Dunn et al. (1982), Feldhamer (1979), Flinders & Chapman (2003), Flux (1983), Flux & Angermann (1990), French et al. (1965), Griffing (1974), Grinnell (1937), Gross et al. (1974), Hall (1946, 1981), Harestad & Bunnell (1979), Haskell & Reynolds (1947), Hawbecker (1942), Hill & Veghte (1976), Hoagland (1992), Hoffmann & Smith (2005), Hoffmeister (1986), Jones et al. (1983), Lawlor (1982), Lechleitner (1958a, 1958b, 1959), Lissovsky (2016), Long, J.L. (2003), Long, W.S. (1940), Maser et al. (1988), Nelson (1909), Orr (1940), Ramirez-Silva et al. (2010), Schmidt-Nielsen et al. (1965), Seton (1928), Smith et al. (2002), Steinberger & Whitford (1983), Stoddart (1984), Swarth (1929), Westoby (1980).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.