Lepus arcticus, Ross, 1819

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625539 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6625486 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03822308-B762-FFDF-FF65-F9D5FDD5F4B3 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Lepus arcticus |

| status |

|

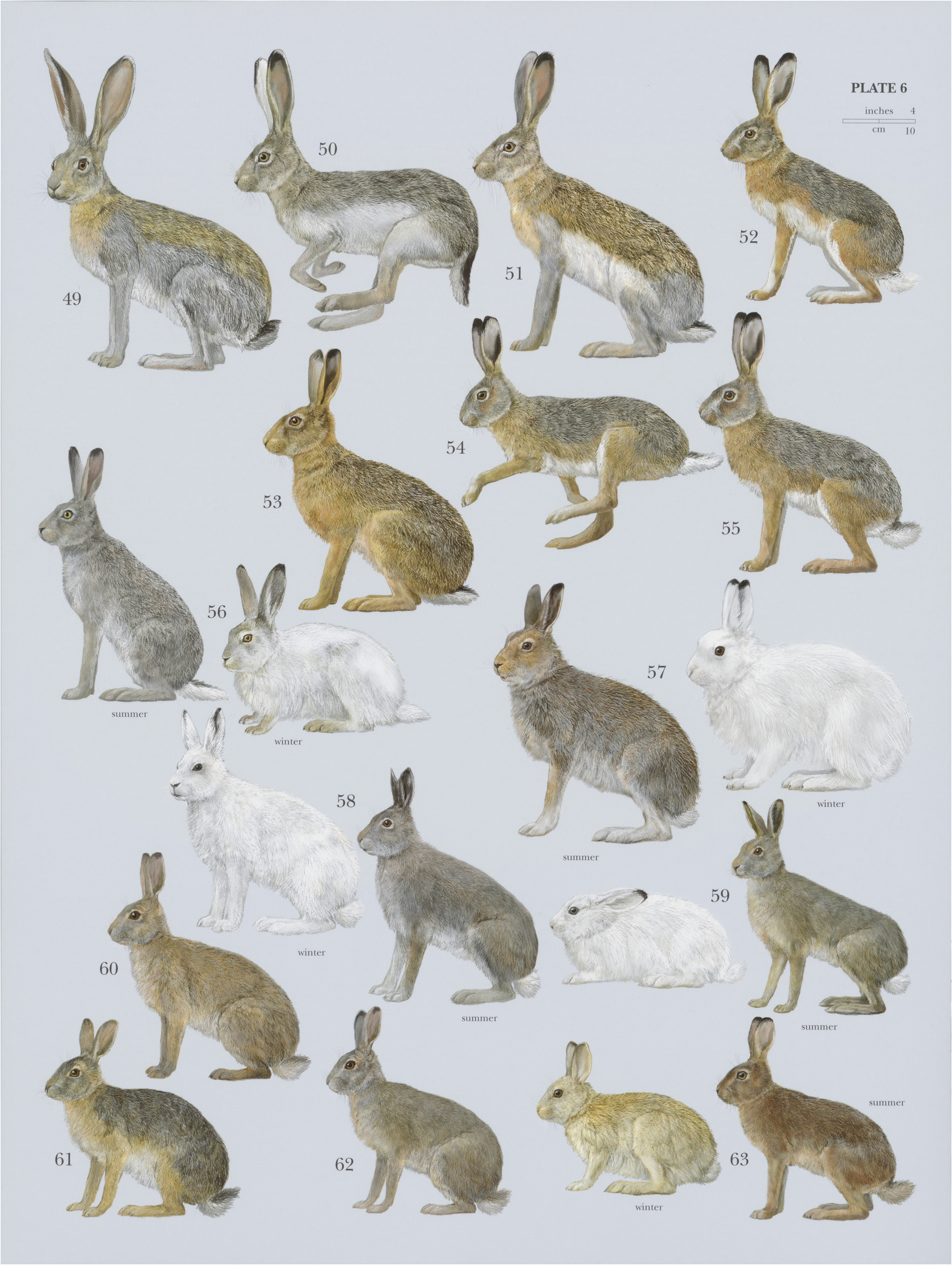

57. View On

Arctic Hare

French: Liévre arctique / German: Polarhase / Spanish: Liebre artica

Other common names: American Arctic Hare, Canadian Arctic Hare, Labrador Hare, Greenland Hare, Polar Hare

Taxonomy. Lepus arcticus Ross, 1819 View in CoL ,

“Southeast of Cape Bowen” (Possession Bay, Bylot Island, latitude 73°37’N, Canada).

Formerly, the three arctic species, L. timidus , L. arcticus and L. othus , were included in L. timidus based on morphological characteristics. This is also supported by genetic analysis of mtDNA, although evidence based only on mtDNA should be treated cautiously. There is also the view that two species exist: L. timidus in the Old World and L. arcticus in Greenland, northern Canada, Alaska, and the Chukchi Peninsula, Russia. Other lagomorph taxonomists consider that L. arcticus is conspecific with L. timidus and distinct from the L. othus . Until conclusive evidence is available, the three species are considered distinct species with L. timidus in the Old World, L. othus in Alaska, and L. arcticus in northern Canada and Greenland. As taxonomists are still trying to clarify the species differentiation in Lepus , the subspecific taxonomy is not elaborated yet. The original descriptions of the subspecies are often not very helpful as they are mostly based on few exterior characteristics and small numbers of individuals. It has been shown that the variability is clinal in more careful investigations. Hence, the distinction in subspecies might be arbitrary and unreasonable. Nine subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

L.a.arcticusRoss,1819—BaffinI,BylotI,andMelvillePeninsula,NENunavut(NCanada).

L.a.andersoniNelson,1934—C&NENorthwestTerritoriesandmostofNunavut(NWCanada).

L.a.bangsiiRhoads,1896—NewfoundlandandNEL.a.(ECanada.)

L.a.banksicolaManning&Macpherson,1958—BanksI,intheCanadianArcticArchipelago.

L.a.groenlandicusRhoads,1896—W,N&NEice-freecoastalregionsofGreenland.

L.a.hubbardiHandley,1952—PrincePatrickI,intheCanadianArcticArchipelago.

L.a.monstrabilisNelson,1934—QueenElizabethIs,exceptPrincePatrickI,intheCanadianArcticArchipelago.

L. a. porsildi Nelson, 1934 — S & SW ice-free coastal regions of Greenland. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 560-660 mm, tail 45-100 mm, ear 80-90 mm, hindfoot 146-164 nm; weight 2.5-6.8 kg. Measurements of Artic Hares vary depending on geographical location. In the north, individuals are larger than in the south. Summer pelage is gray in southern populations and white in northern populations. In winter, Arctic Hares are white except for black ear tips. Winter fur is long and soft. During molt, Arctic Hares remove loose tufts of hair by rolling in snow. Eyes are yellowish brown. Ears are blackish in front and white behind, with a whitish band isolating black tips. Large feet are padded with heavy, yellowish brush of hair. Claws on forefeet and hindfeet are long and well adapted for digging in snow.

Habitat. Tundra, primarily north of the tree line, arctic alpine, and exposed coastal barren areas from sea level to elevations of ¢.900 m. The Artic Hare prefers hillsides or rock-strewn plateaus rather than flat bog land. Throughout most ofits distribution, it spends summer in the tundra north of the tree limit, but in winter, it might penetrate up to 160 km into the forest. Areas with little snow cover and wind exposure are favored, and groups of several hundred Arctic Hares may aggregate in such areas in winter, moving from one place to the other in search for food.

Food and Feeding. The Arctic Hare feeds mainly on woody plants throughout the year. Arctic willow ( Salix arctica, Salicaceae ) is the main species eaten in all seasons, and its leaves, buds, bark, and roots make up to 95% of winter diets. It also feeds on mosses, lichens, buds, and berries of crowberry ( Empetrum niger, Ericaceae ), young blooms of saxifrage ( Saxifraga oppositifolia, Saxifragaceae ), mountain sorrel ( Oxyria digyna, Polygonaceae ), and various kinds of grasses. Summer diets of Arctic Hares are highly variable but mainly contain Arctic willow, mountain avens ( Dryas integrifolia, Rosaceae ), and grasses. On Baffin Island, dwarf willows (S. arctica and S. herbacea) and crowberry are the main food. In Greenland, diets consist of Arctic willow and mountain sorrel. The Arctic Hare regularly feeds on stomach contents of eviscerated Caribou (Rangifer tarandus). Water is obtained by eating snow. It makes trails from one grazing place to the next. Often high places are selected to forage. Arctic Hares dig through snow to find food. If snow has a hard crust, they stamp on it with their forefeet to make a hole. Feeding usually occurs in morning and evening.

Breeding. Mating season of the Arctic Hare occurs in April/May. The male follows the female continuously. During copulation, the male bites the female fiercely on neck and back that she often is covered with blood. Mating corresponds with molting, so fur “flies” during the process. Gestation is c¢.53 days. Young are born in May-July in nests lined with dry grass, moss, and fur from the mother. Nests are either a depression among mosses and grasses or under or between rocks. Females have litter of 2-8 young, with an average of 5-4 young. Females in the far north have one litter per year, and in Newfoundland, average litter size was three young. Newborns are blackish brown, with white bellies, chins, and throats. When threatened, young flatten out on the ground, with their eyes closed and ears pressed tightly on their backs. During the first 2-3 days oflife, the mother stays with her young and defends them against danger. Nursing takes place every 18-20 hours, and nursing bouts lasts 1-4 minutes. By the third day oflife, young hide among stones when danger approaches. After c.2 weeks oflife, young disperse and hide behind rocks appearing only when nibbling on vegetation or nursing. The mother remains near the nursing site. Gradually, young increase their movements to a maximum of c.1 km from where they were born. Juvenile pelage is darker than summer pelage of adults. By the third week of life, young leave their mothers and form nursery bands of up to 20 individuals. Young are weaned at 8-9 weeks old. By late July, they are nearly as large as their parents and are white. Young breed for the first time as yearlings. Adult sex ratio of Arctic Hares is biased toward males.

Activity patterns. The Arctic Hare rests during the day when the sun is shining, but during the dark winter, it has no fixed time for resting. When resting,it usually sits near a large stone, dozing or asleep, sheltered from wind, covered from aerial predators, and warmed by the sun. Usually, it chooses a site a little way up a slope. Arctic Hares often are immobile during resting,sitting crouched, with ears halfway erect and eyes nearly closed. Often 2—4 individuals rest together. In the afternoon, the Arctic Hare often leaves its resting place and starts feeding.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Arctic Hare might be migratory because most individuals in an area disappear during summer, apparently moving northward. In November, they apparently migrate southward. Nevertheless, some researchers do not believe that mass migrations are undertaken by the Arctic Hare. In northern populations, hopping on hindfeet without the forefeet touching the ground has been reported for disturbed and frightened Arctic Hares. Home ranges are 9-290 ha, depending on habitat quality. In Newfoundland,sizes of male home ranges in summer are double the size of female home ranges. Movements increase in March/April with the onset of the mating season. In winter, Arctic Hares may protect themselves from extreme cold by burrowing into snow. These snow dens consist of a tunnel c¢.10 cm in diameter and 30 cm in depth, with an enlarged terminal chamber. The Arctic Hare is usually solitary, but grouping behavior is very characteristic, with groups of 100-300 individuals being observed. In large groups, most individuals might be asleep, but one is usually awake and alert to danger. From early winter until early spring, Arctic Hares form groups of 15-20 individuals. Arctic Hares frequently move among groups. Adults dominate juveniles, and dominance is unrelated to sex or breeding condition. When the mating season starts, groups disperse, pairs are formed, and each pair establishes a small territory. The male usually leaves the female after birth of young but sometimes remains close. Arctic Hares are usually silent, but lactating females may emit a short series of low growls as they approach their nursing places.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List. The Arctic Hare is widespread, and population status seems to be constant although little monitoring occurs. Native people modestly harvest Arctic Hares for food and fur. Southern populations of Arctic Hares might be subject to habitat loss and climate change, although the latter is speculative. Distributions of the Arctic Hare and the Snowshoe Hare ( L. americanus ) slightly overlap, but the two species differ in their habitat preferences. The Arctic Hare occupies treeless barrens or tundra, whereas the Snowshoe Hare inhabits forests. In Newfoundland, replacement of the Arctic Hare by the Snowshoe Hare might be an example of competitive exclusion. Other theories list lack of suitable food or predation by the Canadian Lynx (Lynx canadensis) as causes that limited distribution of the Arctic Hare in Newfoundland.

Bibliography. Angermann (1967a, 2016), Aniskowicz et al. (1990), Audubon (2005), Bakeret al. (1983), Banfield (1974), Barta et al. (1989), Ben Slimen, Suchentrunk & Ben Ammar Elgaaied (2008), Bergerud (1967), Best & Henry (1994a), Bittner & Rongstad (1982), Cameron (1958), Corbet (1983), Dixon et al. (1983), Fitzgerald & Keith (1990), Flux (1983), Flux & Angermann (1990), Gray (1993), Hall (1951), Hamilton (1973), Hearn et al. (1987), Hewson (1991), Hoffmann & Smith (2005), Johnsen (1953), Lissovsky (2016), Loukashkin (1943), Macpherson & Manning (1959), Manniche (1910), Merceret al. (1981), Murray (2003), Murray & Smith (2008b), Nelson (1909), Parker (1977), Pruitt (1960), Richardson (1829a), Soper (1944), Sutton & Hamilton (1932), Waltari & Cook (2005), Wu Chunhua et al. (2005).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.