Platylesches Holland , 1896

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3724.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:7D05BB2E-4373-4AFB-8DD3-ABE203D3BEC1 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7044084 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0385994A-FF87-FFDA-9BFD-FF09FAE9B820 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Platylesches Holland , 1896 |

| status |

|

Platylesches Holland, 1896 View in CoL

This is a genus of at least 20 species, which is restricted to sub-Saharan Africa, and is in need of revision ( Larsen 2005). Early last century, Dollman (unpublished) reared Pl. moritili from Parinari curatellifolia ( Chrysobalanaceae , Malpighiales ) in Zambia, but this record was never published. The Chrysobalanaceae food plants were only rediscovered in the last 30 years. All known food plants are in the Chrysobalanaceae , and the great majority of records are from Parinari spp. Parinari curatellifolia is a large spreading tree up to 13m, characteristic of sandy soils and open deciduous woodland and is seldom cut down as its fruit (mbolola plum) is valued by local people ( Palgrave 1983). It is found through tropical Africa ( National Research Council 2008) to south-west Kenya ( Beentje 1994) and south to northern South Africa ( Palgrave 1983). Maranthes floribunda is a tree of Zambezian woodland ( White et al. 2001) that can easily be confused with Pa. curatellifolia . Parinari excelsa , is a tree associated with forests through West Africa, east to Tanzania (not Kenya) and south to Mozambique, as well as South Africa ( White 1978), and is used as a food plant by Pl. galesa . A third species occurring mainly in southern Africa is the low growing (suffrutex) Pa. capensis , found in sandy areas ( Palgrave 1983), which in suitable habitat can be found as far north as the Mpanda and Tabora Regions of western Tanzania (K. Vollesen, pers. comm., 2013). Recently M. goetzeniana was found abundantly in Mabu forest in Northern Mozambique —it was previously thought to be an Usambara endemic. Other species of Maranthes occur in West Africa—one having been recorded as a food plant of Platylesches in Côte d’Ivoire ( Vuattoux 1999). Other species of Parinari and Maranthes are likely to be food plants. In addition to the eight species of Platylesches we have documented below, two other species are known to feed on Chrysobalanaceae , and Pl. dolomitica Henning & Henning, 1997 , which is considered ‘vulnerable’ in Gauteng Province, South Africa, is suspected to feed on Pa. capensis ( Woodhall 2005, Henning et al. 2009).

There are no food plant records from other plant taxa, except for an early record from South Africa of Pl. galesa feeding on Ehrharta erecta and other grasses ( Murray 1959), which has been repeated in the subsequent literature ( Dickson & Kroon 1978, Kielland 1990, Larsen 1991, Ackery et al. 1995). However, in light of more recent records from Parinari spp. , grasses are now considered doubtful ( Heath et al. 2002) or incorrect ( Larsen 2005, Woodhall 2005). We agree that all records of grasses as food plants should be discounted.

In this series of papers, we have followed the leaf shelter classification and terminology of Greeney & Jones (2003) and Greeney (2009), summarised in Cock (2010), which is based on shelter construction, particularly the number of main cuts used to make a shelter. Congdon et al. (2008) also considered this question, and adopted a functional approach to the classification of leaf shelters, summarised in Cock & Congdon (2011a). This functional classification is especially relevant to the genus Platylesches , and so is presented here again.

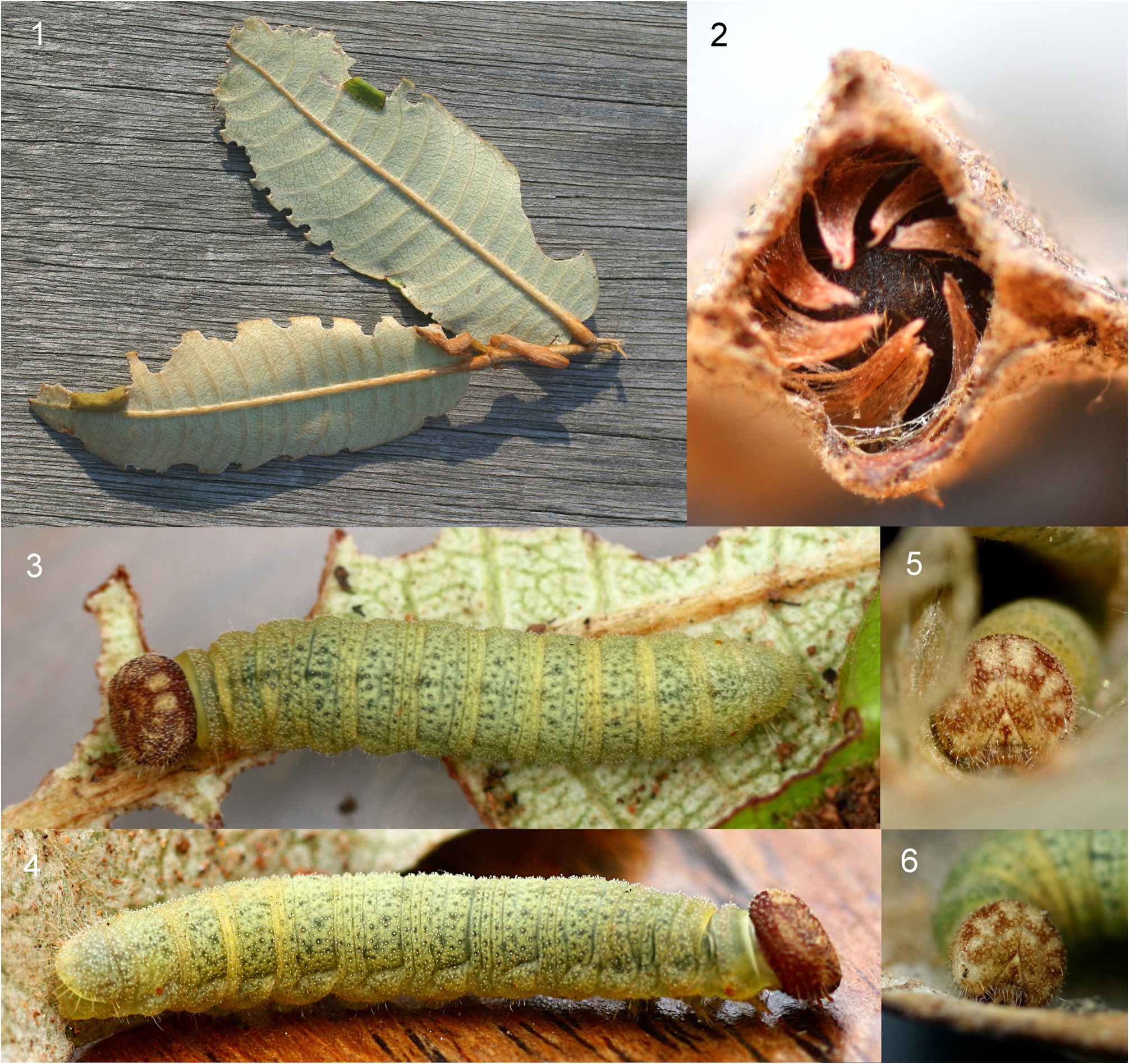

Tube or tubular shelters. The caterpillar folds or rolls a leaf, and eats the leaf from the apex back towards the base, extending the shelter backwards as it goes. When it reaches the base of the leaf it moves to a new one and repeats the process until fully fed. Some species of Hesperiinae which feed on dicotyledons do this, including some Platylesches spp. These Platylesches spp. and the Andronymus spp. treated above feed on flush leaves near the growing point of the plant, completing development quickly before the leaves harden. The following tube shelter builders are treated below: Pl. galesa , Pl. moritili , Pl. neba and Pl. picanini .

Chamber shelters. The caterpillar makes a more or less permanent shelter often in more mature foliage, coming out primarily at night to feed, and returning to the chamber during the day. The caterpillar only makes a new shelter when it outgrows the old one, or when the food source becomes too distant. Most Pyrginae do this ( Cock 2010, Cock & Congdon 2011a, b) and so do some Platylesches spp. These species usually develop more slowly, perhaps because mature foliage is less nutritious. A rearing container containing a single tube species Platylesches caterpillar will contain more frass in the morning than a container of a dozen chamber species caterpillars. Of the Platylesches spp. whose biology is now known, the following are chamber makers: Pl. ayresii , Pl. langa , Pl robustus , Pl. shona and Pl. tina .

In TCEC’s experience, the tube-making Platylesches spp. do not pupate in their shelters, and he has not found their pupae in the wild. If the caterpillars are sleeved out, pupae are found amongst leaf litter in the bottom of the bag or in silk lined cocoons in folds of the bag near the bottom, suggesting that they would normally pupate in litter on the ground. In captivity, the old tubes might constitute leaf litter and be incorporated into a pupation chamber, but caterpillars often pupate under leaves on the bottom of the box. Chamber-making Platylesches spp. , on the other hand, invariably pupate in their shelters, closing the shelter entrances with a circle of elongate triangular flaps ( Figures 64.2 View FIGURE 64 and 68.2 View FIGURE 68 ) or loose threads ( Pl. shona ).

TCEC has reared a further three Platylesches spp. from tube shelters on Pa. curatellifolia in Tanzania, which belong to the group which includes Pl. iva Evans, 1937 and Pl. affinissima Strand, 1920 . Platylesches iva is known from Ivory Coast through Nigeria to Uganda, Malawi and Tanzania, where it is reported from a single butterfly from Dendene Forest, south of Dar es Salaam, although Larsen (2005) doubts the identity of this specimen. Platylesches affinissima is known from West Africa to Malawi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe; in Tanzania it is a western butterfly, with a possible record from the Uluguru Mountains in the east. These caterpillars are rare in TCEC’s experience, and the three raised appear not to agree exactly with either of the two named species. This material, including adults, was documented in Congdon et al. (2008) and repeated here for completeness. Figures 62.1 and 62.2 View FIGURE 62 were each reared once. The narrow head of Figures 62.2 View FIGURE 62 and 6 View FIGURE 6 is unlike any other Platylesches sp. and we do not believe it can represent the same species as Figure 62.1 View FIGURE 62 , yet the adults both come closest to Pl. affinissima , although that of Figure 62.2 View FIGURE 62 is small. Figures 62.3–4 View FIGURE 62 show another species reared twice, the adults of which are close to Pl. iva . The taxonomy of these specimens has yet to be resolved, but will be addressed in T.B. Larsen’s revision of the Afrotropical Hesperiidae , or in an anticipated addendum part to the present series.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Hesperiinae |