Notamacropus eugenii (Desmarest, 1817)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6723703 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6722586 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03950439-9677-FF93-6F67-F5EFF9FF32A4 |

|

treatment provided by |

Tatiana |

|

scientific name |

Notamacropus eugenii |

| status |

|

58. View Plate 42: Macropodidae

Tammar Wallaby

Notamacropus eugenii View in CoL

French: Wallaby tammar / German: Derby-\ Wallaby / Spanish: Ualabi tammar

Other common names: Dama Wallaby, Kangaroo Island Wallaby

Taxonomy. Kangurus eugenu Desmarest, 1817 ,

“ Iile Eugene [= St. Peters Island] ,” Nuyt’s Archipelago , South Australia, Australia.

Previously placed in genus Macropus , within which moved into subgenus Notamacropus in 1985; in 2015 Notamacropus was elevated to full genus status. Although this species is morphologically variable across its range, preliminary genetic studies identify only two major lineages. Further study required. Two subspecies currently recognized.

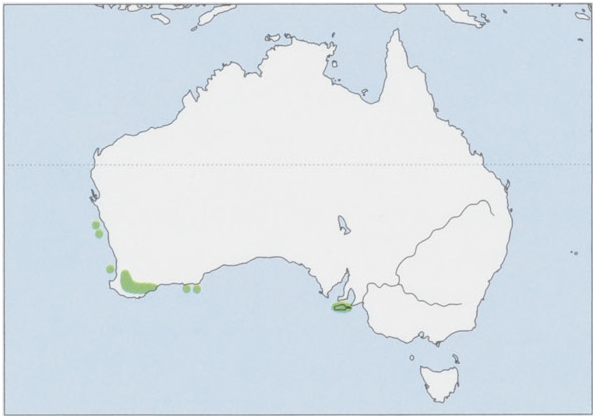

Subspecies and Distribution.

N.e.eugeniiDesmarest,1817—KangarooI,SouthAustralia.

N. e. derbianus Gray, 1837 — SW Western Australia, including East and West WallabiIs (Houtman Abrolhos Archipelago), Garden I (off S Perth), and Middle I and North Twin Peak I (Recherche Archipelago). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 59-68 cm (males) and 52-63 cm (females), tail 38-45 cm (males) and 33-44 cm (females); weight 6-10 kg (males) and 4-6 kg (females) for N. e. eugenii ; mean weight 4-6 kg (males) and 3-7 kg (females) for N. e. derbianus. A small, short-tailed, stocky, thickly furred wallaby that hops with arms held away from body. N. e. eugenii is dark gray-brown dorsally, heavily grizzled with pale-tipped hairs; paler (light brown to cream) ventrally, with dark gray underfur. Shoulders, limbs, and flanks often paler, light brown to rufous brown, although digits dark. Dark middorsal stripe of variable thickness, intensity, and length from crown to mid-back. Pale cheek stripe of variable intensity on muzzle to below eye. Ears largely hairless inside, although inner base and lower margins pale gray to off-white; outside of ears dark gray at base, becoming darker and less well furred toward tips. Tail short, thick, and well covered with short fur; typically of same color as body dorsally, but paler ventrally. N. e. derbianus is typically smaller, with overall coloration paler and more brown, limbs more strongly rufous, and tail darker and grayer; individuals from North Twin Peak Island, however, are very dark and reddish, while those from Middle Island are grayer. Diploid chromosome number of both subspecies is 16.

Habitat. Dense coastal scrub and heath, as well as dry sclerophyll forest, eucalypt woodland, and mallee with shrubby understory or dense thickets. Shelters in low dense vegetation; forages in more open areas nearby. Can occur in urban areas, foraging on lawns and roadsides.

Food and Feeding. Poorly known. Appears preferentially to consume grasses, but large amounts of browse from shrubs and trees are also eaten at some sites. Herbs and seeds, as well as tree and shrub seedlings, are also consumed. Adults frequently lose body condition over summer dry season, as food becomes limiting. Some island populations survive dry summers by drinking seawater.

Breeding. Only N. e. eugenii on Kangaroo Island has been well studied. Females reach sexual maturity from nine months and males from 24 months. Breeds seasonally, producing young from mid-summer to early winter, but mostly mid-January to February, which results in most young vacating the pouch in spring. Females typically give birth to a single young, although twins are occasionally reported. Overall sex ratio at birth is usually close to parity, but females in better condition tend to produce more male pouch young. During especially dry summers mortality of pouch young may reach 50%. Exhibits embryonic diapause and post-partum estrus, females mating within hours of giving birth. Unless incumbent pouch young is lost before winter solstice, an embryo conceived in one breeding season will remain in diapause until following breeding season, up to eleven monthslater. The estrous cycle is 28-32 (mean 30) days and gestation 28-31 (mean 29) days. Young spend 8-9 months in the pouch and are weaned at about ten months; after permanent pouch emergence, young accompany their mother as a young-at-foot until after weaning. The mating system appears promiscuous. There is intense competition among males during breeding season for access to females. Males begin to show interest in females about a month before estrus and associate closely with them from parturition. Estrous females attract multiple males,resulting in frequent chases of female by males, as well as intense inter-male aggression. The locally dominant male, usually the largest, closely guards the estrous female and tries to keep other males away. He usually matesfirst with the female, but copulation is frequently disrupted by rival males. If not interrupted, copulation is concluded in 6-8 minutes, then dominant male continues to guard female for up to eight hours; up to seven other males may then mate with female. The large testes in this species suggest that intense sperm competition occurs. Genetic studies in captive colonies show that dominant males sire only c¢.50% of offspring.

Activity patterns. Largely nocturnal. Shelters in low dense vegetation during day; becomes active late afternoon, moving along established runways to emerge around dusk in more open grassy areas. Forages mostly within 50 m of cover. Rarely moves into open areas until after dark and typically returns to cover before sunrise. Feeding activity often reduced in bad weather. Moon phase had no effect on nocturnal activity in captivity, but foraging increased underartificial light.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Poorly known. Home ranges (100% minimum convex polygon) are similar for males and females, but are significantly larger in summer (42 ha) than in winter (16 ha). Home ranges of both sexes show extensive overlap with those of other individuals and appear relatively stable over time, although individuals have been recorded as moving up to 16 km over a 12-15month period. Moderately gregarious. Forages in closely spaced groups, with individuals less than 10 m apart; looser aggregations of more than 20 individuals can occur in favored feeding areas. When in open areas, individuals devote more time to feeding and less to vigilance as group size increases. In captivity, females are less aggressive toward related individuals.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. South Australian mainland population is listed as extinct in Australia. As a consequence of habitat loss through clearing for agriculture, and predation by introduced Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes), the Tammar Wallaby has declined significantly in last 150 years, with many local extinctions. Distribution in Western Australia (where formerly distributed from north of Geraldton, on west coast, to Cape Arid, on south coast) has contracted to south and west, while populations on South Australian mainland (Eyre, Yorke, and Fleurieu Peninsulas; Adelaide Hills), as well as islands of St Peters, St Francis, Flinders, and Thistle, have become extinct. The species remains abundant, however, on fox-free Kangaroo Island, the largest South Australia island, where it is often regarded as an agricultural pest and is regularly culled. This population appears to have benefited from habitat fragmentation and the establishment of improved pasture. In South Australia, Tammar Wallabies were introduced to islands of Boston, Greenly, Granite, and Wardang, although several of these populations were subsequently removed following damage to vegetation. This species has also become a pest in New Zealand, where it was introduced to Kawau Island in 1870s and subsequently (c.1912) to near Rotorua, in the North Island. While these introduced populations have been regularly culled for decades, the Kawau Island population is currently the focus of an eradication program. Genetic studies have suggested that the Tammar Wallabies introduced to New Zealand derived from mainland South Australia; some individuals have since been returned to Australia and reintroduced to Innes National Park, South Australia. In south-west Western Australia, the remnant mainland populations of this wallaby have benefited from widespread fox control and reintroductions. The species now occurs in multiple protected areas and in 1998 was removed from the Western Australian list of threatened fauna. A population introduced to North Island in 1980s, from West Wallabi Island (in Abrolhos Archipelago), has been culled several times since 2008 to reduce the wallabies’ impact on native vegetation. The indigenous Western Australian island populations all occur within protected areas, but have low genetic diversity and remain vulnerable to severe drought, wildfire, introduced predators, competitors, or disease. Tammar Wallabies from Kangaroo Island are well established in captivity. Additional studies of the species’ taxonomy and ecology, particularly diet and habitat preferences, ranging behavior, and reproduction in the field, are required throughout its range.

Bibliography. Andrewartha & Barker (1969), Bell et al. (1987), Berger (1966), Biebouw & Blumstein (2003), Blumstein & Daniel (2002), Blumstein, Ardron & Evans (2002), Blumstein, Evans & Daniel (1999), Calaby & Grigg (1989), Chambers & Bencini (2010), Chambers et al. (2010), Copley (1995), Dawson & Flannery (1985), DEC (2012a), DEH (2004), Dressen & Hendrichs (1992), Eldridge, Kinnear, Zenger et al. (2004), Groves (2005b), Hadley et al. (2009), Hayman (1989), Herbert (2007), Hinds (2008), Hinds & den Ottolander (1983), Hinds & Tyndale-Biscoe (1982, 1985), Hinds et al. (1989), Hynes et al. (2005), Inns (1980), Jackson & Groves (2015), King (2005), Kinnear et al. (1968), Lentle et al. (1998), Maxwell et al. (1996), McMillan et al. (2010), Menkhorst & Knight (2001), Merchant (1979), Miller, Eldridge & Herbert (2010), Miller, Eldridge, Morris et al. (2011), Morris, Friend, Burbidge & van Weenen (2008), Murphy & Smith (1970), van Oorschot & Cooper (1989), Paplinska et al. (2010), Poole & Brown (1988), Poole et al. (1991), Renfree et al. (1989), Robert & Braun (2012), Robert & Schwanz (2013), Robert et al. (2010), Robinson et al. (1996), Rose et al. (1997), Rudd (1994), Schwanz & Robert (2012), Shapiro et al. (2011), Shaw & Pierce (2002), Shepherd et al. (1997), Sunnucks & Taylor (1997), Taggart, Breed et al. (1998), Taylor & Cooper (1999), Taylor et al. (1999), Tyndale-Biscoe et al. (1974), Warburton (1986, 1990), Williamson et al. (1990), Wodzicki & Flux (1967), Woinarski et al. (2014ab, 2014ac, 2014ad), Wright & Stott (1999).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Macropodiformes |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Notamacropus eugenii

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Kangurus eugenu

| Desmarest 1817 |