Osphranter antilopinus, Gould, 1842

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6723703 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6722552 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03950439-9679-FF9D-6F64-FA3FFC7133B2 |

|

treatment provided by |

Tatiana |

|

scientific name |

Osphranter antilopinus |

| status |

|

51. View Plate 42: Macropodidae

Antilopine Wallaroo

Osphranter antilopinus View in CoL

French: Wallarou antilope / German: Antilopenkanguru / Spanish: \ Walaro antilope

Other common names: Antilopine Kangaroo

Taxonomy. Osphranter antilopinus Gould, 1842 View in CoL ,

“ Port Essington, North coast of Australia.”

Previously placed in genus Macropus , within which moved into subgenus Osphranter in 1985; in 2015 Osphranter was elevated to full genus status. Monotypic.

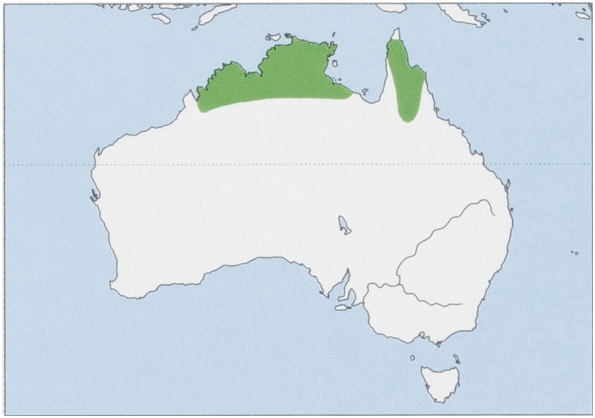

Distribution. N Australia from the SW Kimberley, Western Australia, to Pungalina , E Northern Territory; disjunct population also on Cape York Peninsula, Queensland. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 83-120 cm (males) and 73.3-93.5 cm (females), tail 74-596 cm (males) and 66.4-81.3 cm (females); weight 18.6-51 kg (males) and 14-24.5 kg (females). A large, lean, sexually dimorphic, short-furred wallaroo. Males reddish brown dorsally, face sometimes grayish, paler to almost white ventrally and on lower limbs and tail. Females paler and often more gray, especially on head and shoulders. Snout short and bulbous, especially in male; muzzle black, cheeks pale; insides and margins of ears pale. Paws and digits of feet blackish brown. Tail darker dorsally and sometimes distally. Diploid chromosome number is 16.

Habitat. Tropical monsoon forest and woodland with grassy understory, mostly on flat or gently undulating terrain. Access to permanent water and recent late-dry-season fires are positively correlated with abundance. Uncommon in agricultural and periurban areas.

Food and Feeding. A grazer, consuming mostly grasses and sometimes a small amount of forbs.

Breeding. Poorly known. May be able to breed throughout year, females producing one young per pregnancy, but most births appear to occur toward end of wet season (March-April). Embryonic diapause has not been confirmed and post-partum estrus appears not to occur. The estrous cycle is 36-50 (mean 41) days and gestation 33-34 (mean 34) days. Young spend about nine months in the pouch and typically emerge at start of wet season. After permanent pouch emergence, young accompanies the mother as a young-at-foot until after weaning, which occurs at c.15 months. Adult males are significantly larger than adult females and have well-developed forelimbs, suggesting intense competition among males for access to females. Males establish dominance relationships through repetitive, ritualized bouts of allogrooming, display, sparring, wrestling, and kicking. Males test the estrous state of females by eliciting urination, nosing the stream, and exhibiting overt flehmen (lip-curl).

Activity patterns. Primarily nocturnal; during daylight hours multiple individuals rest in adjacent hip-holes dug undertrees or bushes. Becomes active in late afternoon, often moving into more open areas to feed until early morning, when it returns to cover. On wet or overcast days may be active at any time.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Probably sedentary, although may undertake small-scale migration from floodplain to higher ground in wet season. Home-range estimates (95% Fourier transform, MAP95) are limited: 79 ha and 102 ha for two adult males and 14 ha for an adult female. Gregarious, occurs in groups of up to 30. Most common group size is 2-5, and is positively related to population density. Group membership is open, and group size and composition change frequently. Mixed-sex groups occur throughout year, but large males associate strongly with females having large pouch young in wet season, while single-sex groups are more common in dry season. Adult females and large adult males are more frequently found in higher-quality habitat. Large males are often found alone, as they move between groups while checking reproductive status of adult females. Genetic data suggest that dispersal is sex-biased, females showing highersite philopatry. Disjunct Queensland and Northern Territory populations are not highly divergent genetically and appear to be connected by occasional male-mediated gene flow. Aggregations of up to 50 individuals can occur on foraging areas; whether this represents a stable mob, consisting of overlapping and frequently interacting individuals, has not yet been demonstrated.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Antilopine Wallaroo is widely but patchily distributed. It occurs in several protected areas, but amount of high-quality habitat protected is limited in some regions. It is not currently subject to any major threats, but there are reports that it is declining. It continues to be hunted by Aboriginal people in some areas. Modeling suggests that it is vulnerable to the impact of climate change. Additional research into this species’ ecology, reproduction, and the likely impact on it of cattle grazing and altered fire regimes 1s required.

Bibliography. Bulazel et al. (2007), Coulson & Croft (1981), Croft (1982b, 1987), Dawson & Flannery (1985), Eldridge et al. (2014), Groves (2005b), Harris, D.B. et al. (2014), Jackson & Groves (2015), Johnson (2003), Menkhorst & Knight (2001), Poole & Merchant (1987), Price et al. (2005), Ritchie (2008, 2010), Ritchie & Bolitho (2008), Ritchie, Martin, Johnson & Fox (2009), Ritchie, Martin, Krockenberger et al. (2008), Russell & Richardson (1971), Woinarski, Ritchie & Winter (2008), Ziembicki et al. (2013).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Macropodiformes |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Osphranter antilopinus

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Osphranter antilopinus

| Gould 1842 |