Kaprosuchus saharicus, Sereno & Larsson, 2009

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.3897/zookeys.28.325 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A979ECDE-871F-4AFC-9ABA-63A0FD6DC323 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3790369 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/1951A16E-5AD8-4959-AB6B-666D02B22049 |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:1951A16E-5AD8-4959-AB6B-666D02B22049 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Kaprosuchus saharicus |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Kaprosuchus saharicus sp. n.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:1951A16E-5AD8-4959-AB6B-666D02B22049

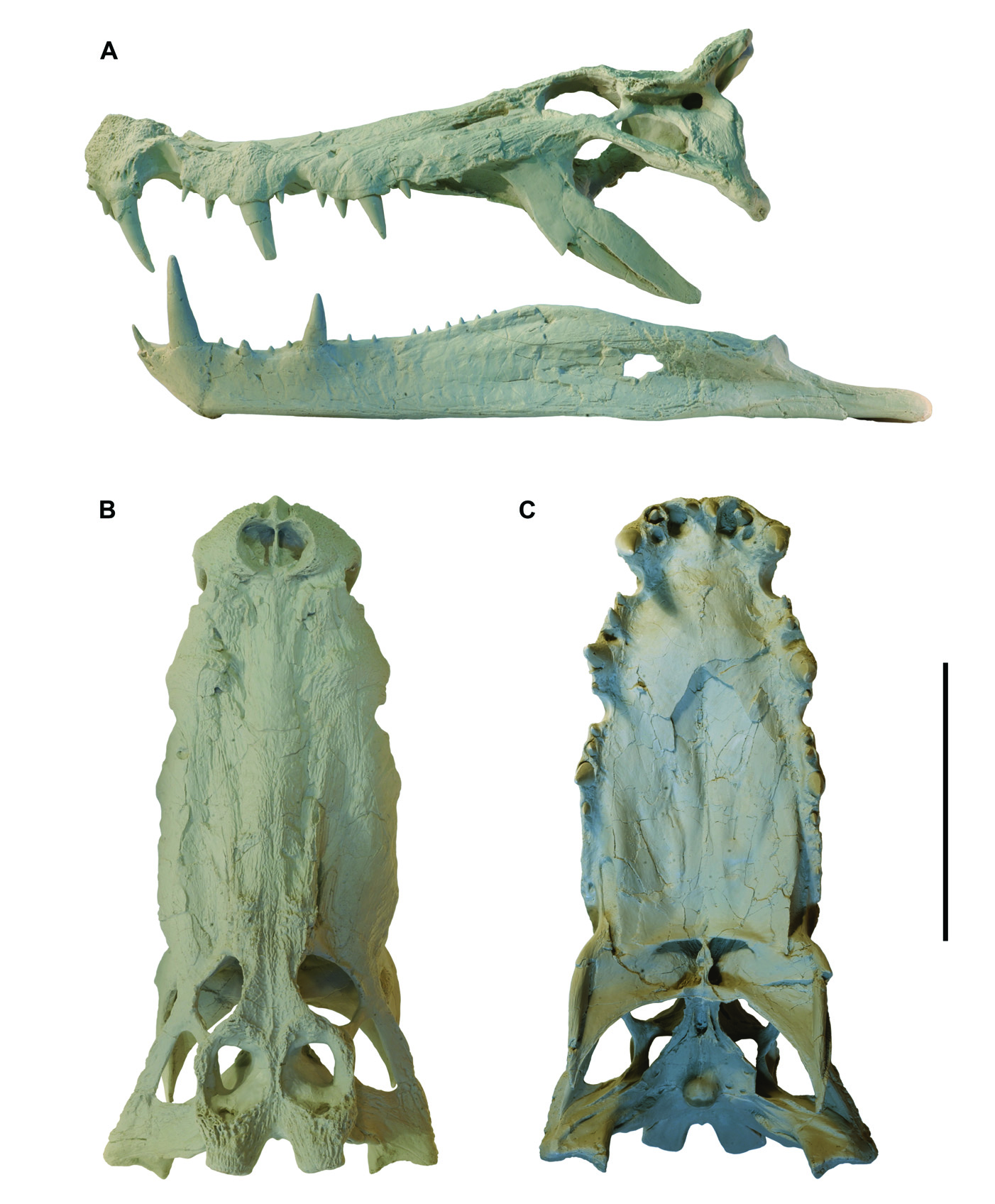

Figs. 32–36 View Figure 32 View Figure 33 View Figure 34 View Figure 35 View Figure 36

Tables 10, 11

Etymology. Sahara, Sahara Desert; - icus, belonging to (Greek). Named for the region where the holotype was discovered.

Holotype. MNN IGU12 ; nearly complete skull missing only portions of the right postorbital, squamosal and the middle one-third of the braincase.

Type locality. Iguidi (west of In Abangharit), Agadez District, Niger Republic (N 17° 56’, E 5° 37’) (Fig. 1A).

Horizon. Echkar Formation, Tegama Series; Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian), ca. 95 Mya ( Taquet 1976). In association with the crocodyliform Laganosuchus thaumastos , the abelisaurid Rugops primus , the spinosaurid Spinosaurus sp., the carcharodontosaurid Carcharodontosaurus iguidensis , an unnamed rebbachisaurid and titanosaurian sauropods.

Diagnosis. Mid-sized (̴ 6 m) neosuchian with the cranium characterized by parasagittal premaxillary rugosities separated by smooth margins near the midline and along the ventral alveolar margin; median keel formed along interpremaxillary suture; circumnarial fossa absent external to the rim of the external nares; rim of external nares telescoped above snout and internarial bar; premaxillary medial process forms posterior margin of the narial rim; nasal forms all of the internarial bar; lacrimal anterior ramus extends anterior to the antorbital fossa; jugal notch for surangular shifted strongly dorsomedially; fossa on jugal dorsal to coronoid process; supratemporal bar with parasagittal orientation; rugose, posterodorsally projecting squamosal-parietal horn; pneumatic spaces within the supratemporal fossa project into the base of the squamosal-parietal horn; anterior palate transversely convex and posterior palate transversely concave; choanal fossa subquadrate; choanal septum expanded ventrally with lenticular shape; and suborbital fossa transversely narrow and facing laterally.

Diagnostic features of the lower jaws include a dentary symphysis with long axis canted posteroventrally at 45° from the horizontal; surangular attachment process immediately posterior to the mandibular flange; angular ventral margin everted; hypertrophied retroarticular process (equaling quadrate length and three times the width of the quadrate condyles); retroarticular process with lateral ridge; axis of retroarticular process diverges posterolaterally; and the retroarticular ramus of the angular expands transversely toward the distal extremity of the process.

Diagnostic features of the dentition include hypertrophied premaxillary, maxillary and dentary caniniforms extending dorsal and ventral to the maxilla and dentary, respectively; nearly straight, labiolingually compressed crowns; pm1 rotated so that the lingual crown surface faces posterolaterally to oppose d1 caniniform; small noncaniniform maxillary teeth; d1 and d2 project dorsally into premaxillary pits, d1 enlarged relative to d2; and d3 (rather than d4) constitutes the lower caniniform.

Dorsal skull roof. The cranium of Kaprosuchus presents a unique morphological hybrid that combines aspects of two of the cranial forms commonly encountered among crocodylomorphs ( Langston 1973; Brochu 2001). Th e snout has generalized proportions with a dorsally opening naris. Normally the teeth in this skull form are subconical and of moderate length, and the posterior skull of moderate depth. In Kaprosuchus , by contrast, the generalized snout is paired with hypertrophied, labiolingually compressed caniniforms and a posterior skull with deep proportions ( Figs. 32–34 View Figure 32 View Figure 33 View Figure 34 ).

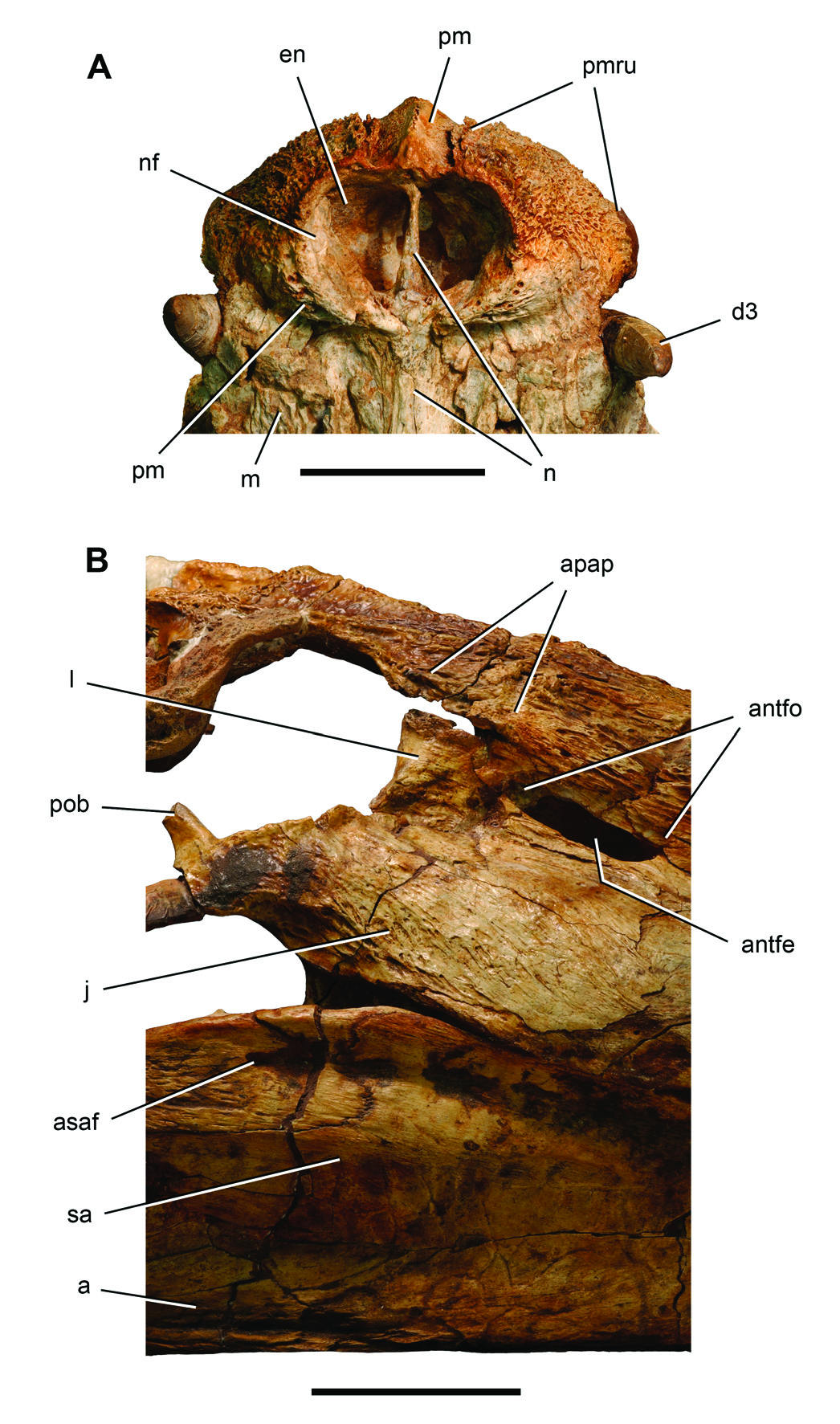

The external nares are telescoped dorsally with a sharp rim ( Fig. 35A View Figure 35 ). In profile ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ), the snout ascends as it joins the orbital rim and skull table, beyond which the squamosal horns project at a conspicuous angle ( Fig. 36A View Figure 36 ). The antorbital fenestra is narrow but elongate and partially surrounded by a fossa ( Fig. 35B View Figure 35 ). Despite the dorsoventrally flattened snout, the subcircular orbits open laterally more than vertically and are angled anteriorly, suggesting that there may have been overlap in the visual fields ( Fig. 36A View Figure 36 ). Th e supra- and laterotemporal fenestrae are relatively small, reflective of the relatively short skull table ( Figs. 33B View Figure 33 , 34B View Figure 34 ).

Most of the cranial surface has linear sculpting, with subcircular pitting predominant only on the frontals. Two aspects of surface texture require special comment. The anterior surface of the premaxilla has a raised rugose texture with several neurovascular openings ( Figs. 35A View Figure 35 , 36 View Figure 36 ). The second unusual feature is branching impressed vessel tracts, a pair of which emerge from the anterior end of the antorbital fenestra ( Figs. 33B View Figure 33 , 34B View Figure 34 ). Th e more posterior of these tracts bifurcates distally, with one sub-branch curving ventrally to the alveolar margin by maxillary tooth 7 and a second sub-branch curving posteriorly onto the anterior end the jugal. The more anterior of these tracts courses anteriorly along the snout margin, with a pair of sub-branches curving to the alveolar margin by the diastema and by the posterior margin of the third maxillary caniniform ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ).

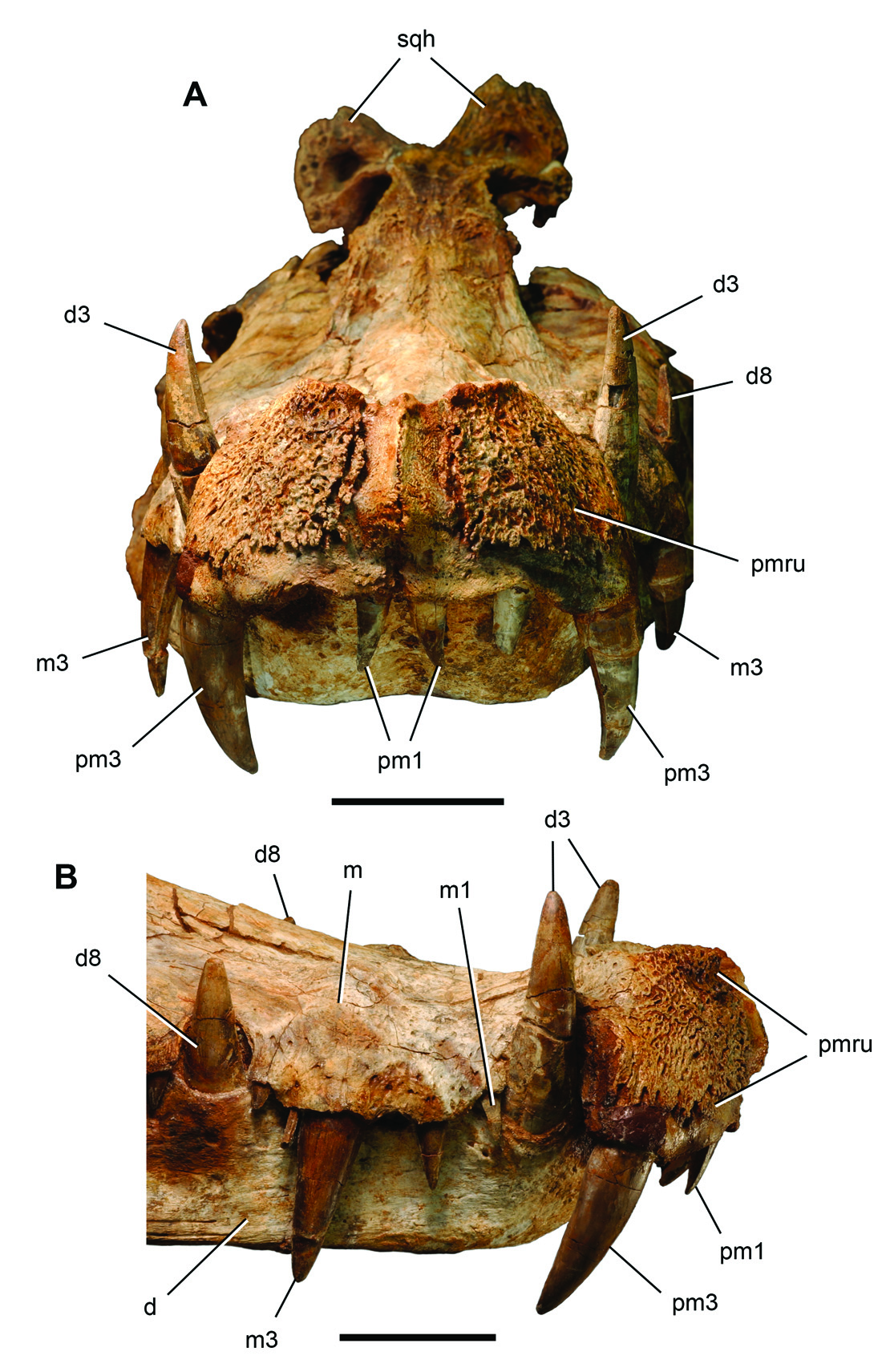

The premaxilla forms the broad snout end ( Figs. 33 View Figure 33 , 34 View Figure 34 , 35A View Figure 35 , 36A View Figure 36 ). Most of the external surface of the bone has a rugose texture that is sharply delimited by smooth margins along the interpremaxillary suture medially and along the alveolar margin ventrally. As a result, the paired rugosity strongly resembles a well-trimmed “mous- tache” in anterior view ( Fig. 36A View Figure 36 ). Th e edges of the rugosity are elevated above the body of the premaxilla, suggesting that the rugosity is a product of secondary growth. This surface likely supported a keratinous shield of some kind, as is often the case for rugose, elevated, vascularized bone among extant amniotes.

The alveolar margin of the premaxilla is rounded and gently scalloped between the premaxillary teeth. the alveolar margin descends toward the large alveolus of the caniniform pm3. In the midline, the interpremaxillary suture lies in a trough near the alveolar margin but projects as a crest between the rugosities ( Fig. 36A View Figure 36 ). Th e rim of the external naris is gently everted ( Fig. 36A View Figure 36 ). In dorsal view, swollen premaxillary processes extend the elevated rim to the posterior side of the external naris ( Fig. 35A View Figure 35 ). The posterior ramus of the premaxilla meets the maxilla along a raised suture. The medial margin of the ramus approaches the midline, reducing the nasals to a narrow fused median strut ( Figs. 33B View Figure 33 , 34B View Figure 34 ).

The medial two-thirds of each maxilla is oriented horizontally whereas the lateral one-third is oriented vertically. In lateral view, the anterior end of the maxilla is deeply notched to accommodate a large caniniform d3 ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ). A large dorsal bulge is present over the caniniform m3 to accommodate its root ( Fig. 36B View Figure 36 ). Three distinct ridges are present on the dorsal aspect of the maxilla. The first curves posteromedially from the notch for the caniniform d3 to the maxilla-nasal suture; the second curves from the alveolar bulge over the caniniform m3 to the maxilla-nasal suture; and the third arises along the dorsal margin of the antorbital fenestra. Th e second and third ridges join posterodorsally to form a V-shaped junction on the prefrontal, which is located dorsal to the posterior end of the antorbital fenestra. Th e posterior rami of the maxilla diverge. Th e posteroventral ramus maintains a horizontal orientation, whereas the posterodorsal ramus ascends at 45° toward the orbital rim.

The nasal is elongate, transversely arched, and fused to its opposite anteriorly and along its mid-section ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ). The nasals form all but the anteriormost extremity of the internarial bar. Th e nasals contact the frontals along a transverse interdigitating suture. The nasal-maxilla suture has a fine saw-tooth pattern, with projections on the nasal pointed anterolaterally.

The prefrontal has anterior, posterior and ventral rami. Th e subrectangular anterior ramus is the longest, butting at its anterior extremity against a notch in the nasals along a slightly elevated squamous suture. At mid-length along this ramus, there is a raised, rugose V-shaped ridge, proximal to which is an arcuate groove. Th e central body of the prefrontal is inset for attachment of an anterior palpebral ( Fig. 35B View Figure 35 ). Th e tapered posterior end of the subtriangular posterior process is inset into frontal along the orbital rim, which is gently everted. Its dorsal surface is recessed before meeting the frontal medially along a raised suture ( Fig. 35B View Figure 35 ). Th e ventral ramus must have tapered strongly in width, angling toward the midline, where the base of the “pillar” is preserved. It expands anteroposteriorly to form a solid buttress to the palatine on the palate.

The central body of the lacrimal is subquadrate, from which extend a long anterior and a short ventral ramus. Nearly all of this bone is oriented in a vertical plane. The orbital margin is beveled, presenting a smooth surface in lateral view ( Fig. 35B View Figure 35 ). Th e dorsal edge of the anterior ramus is everted and rugose, joining the prefrontal along a ridge dorsal to the antorbital fenestra. Th e lacrimal forms the C-shaped posterior margin of this fenestra, contributing to its ventral margin and half of its dorsal margin. Th e lacrimal also forms most of the antorbital fossa, which is located on the dorsal side of the fenestra ( Fig. 35B View Figure 35 ).

The frontal is fused to its opposite. Th e composite element is diamond-shaped in dorsal view, with interdigitating nasal and parietal sutures anteriorly and posteriorly. The fused interfrontal suture is raised into a low sagittal crest ( Figs. 33B View Figure 33 , 34B View Figure 34 ). The orbital margin is slightly everted ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ). Th e frontal is excluded from entering the supratemporal fossa by the parietal and postorbital, the latter contacting the frontal along an interdigitating suture.

The parietal is fused to its opposite forming a very narrow skull table between the supratemporal fossae ( Figs. 33B View Figure 33 , 34B View Figure 34 ). Th at surface is rugose, depressed in the midline, and raised into a sharp edge along the medial rim of the supratemporal fossa, closely resembling the condition in Mahajangasuchus ( Turner and Buckley 2008) . The posterior edge of the parietals overhangs the occiput forming a posterior cranial margin that would have extended at least 1 cm beyond the occiput. Th e posterolateral portions of the parietals extend even further posterodorsally to form the medial portion of the base of the squamosal horn. Th at interdigitating parietal-squamosal suture passes anterolaterally along the medial margin of the enlarged foramen within the fossa. The ventral contact with the supraoccipital has a pneumatic recess, suggesting that the mastoid antrum in the supraoccipital likely passed dorsally into the parietal.

The triradiate postorbital forms the posterior margin of the orbit, anterolateral margin of the supratemporal fenestra, and anterior margin of the laterotemporal fenestra. The medial process is broad, its posterior one-third devoted to the smooth margin of the supratemporal fossa. The subtriangular posterior process is deeply notched laterally for the anterior process of the squamosal. Th e ventral process is inset and continuous posteriorly within the auditory fossa.

The tetraradiate squamosal has anterior, medial, posterior and posterodorsal rami, although only the medial and posterodorsal rami are preserved. Th e medial ramus forms most of the posterior margin of the supratemporal fenestra and surrounds the enlarged pneumatized opening to the posttemporal canal. Th e novel posterodorsal ramus is an elaboration of the posterior margin of the skull table ( Fig. 32 View Figure 32 ). It extends posterodorsally from the skull table at least two centimeters posterior to the occiput and has a markedly pitted and rugose surface. Broken along its distal edge, the process may have been longer and/or continued in keratin. Even at its preserved length, it is particularly prominent in anterior view of the skull ( Fig. 36A View Figure 36 ). Other crocodylians have been reported with squamosal horns, the most exaggerated occurring in “ Crocodylus ” robustus ( Brochu 2006). In this case and other crocodylids, the horn is an elaboration of the lateral edge of the squamosal rather than the posterior margin, and there is no contribution from the parietal.

The jugal has anterior, dorsal and posterior rami and forms the slightly everted ventral margin of the orbit. The anterior ramus is tongue-shaped and particularly broad, whereas the posterior ramus is strap-shaped. Both are oriented so they are more broadly exposed in dorsal than lateral views ( Figs. 33A, B View Figure 33 , 34A, B View Figure 34 ), as in Mahajangasuchus ( Turner and Buckley 2008) . Furthermore, as in Mahajangasuchus , the anterior and posterior rami are separated by a deep embayment, such that in lateral view the ventral margin of the anterior ramus is angled posterodorsally whereas that of the posterior ramus angles posteroventrally ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ). Distinctive fossae are also present on each ramus, facing laterally on the anterior ramus and ventrally on the posterior ramus, again as in Mahajangasuchus ( Turner and Buckley 2008) .

The V-shaped quadratojugal forms a broad plate at the posterior corner of the laterotemporal fenestra. The anterior ramus and the anterior one-half of the dorsal ramus are textured. Th e quadratojugal extends toward the lateral quadrate condyle, wrapping onto its ventral side, but does not participate in the jaw articulation. The quadratojugal-quadrate suture is visible near the jaw articulation but fuses as it passes anterodorsally. Th e dorsal contacts of the quadratojugal are not preserved.

Palate. The premaxillary palate is exposed only near the alveolar margin, where there are located two deep fossae, which accommodate the crowns of the first and second dentary teeth. The first dentary tooth is larger than the second, and the fossa on the premaxilla is correspondingly very large, its anterior margin extending between pm1 and pm2 to reach the anterior margin of the premaxilla ( Figs. 33C View Figure 33 , 34C View Figure 34 ). A second smaller fossa for the smaller d2 is located posterior to pm2. Although uncommon, an enlarged anteriorly placed fossa on the premaxillary palate separating pm1 and pm2 occurs in some extant crocodylians such as Osteolaemus (Iordansky 1983) . Mahajangasuchus has an enlarged d1 ( Buckley and Brochu 1999) and apparently has a premaxillary palate with a similarly positioned enlarged fossa ( Turner and Buckley 2008). The palatal shelves of the maxillae contact along their length and form a broad, U-shaped secondary palate that appears to curve ventrally from the premaxillary palate ( Figs. 33C View Figure 33 , 34C View Figure 34 ).

The palatine forms most of the broad posterior one-half of the secondary palate ( Figs. 33C View Figure 33 , 34C View Figure 34 ). A slender process extends between the maxillae anteriorly. Posteriorly, the palatine forms the straight, nearly transverse anterior margin of the choana. Laterally, the palatine expands but does not reach the narrow suborbital fenestra, separated from that opening on both sides of the palate by a narrow contact between the maxilla and pterygoid. Th is unusual condition is absent in Anatosuchus ( Figs. 5C View Figure 5 , 6C View Figure 6 ), Araripesuchus (Figs. 14C, 15C), Mahajangasuchus ( Turner and Buckley 2008) and may be unique among crocodyliforms. The suborbital fenestrae are shifted to the lateral edge of the palate. Because the lateral margin formed by the maxilla and ectopterygoid ui shifted dorsally, the fenestra opens laterally as much as ventrally and is nearly obscured in ventral view ( Figs. 33C View Figure 33 , 34C View Figure 34 ). In this regard, Kaprosuchus is clearly derived and quite distinct from the aforementioned crocodyliforms ( Turner and Buckley 2008).

The pterygoid, fused to its opposite, has a broad palatal ramus that forms the remainder of the border of the choana and extends laterally over the palatines to border the suborbital fenestra. Th e lateral border of the choana is flat and lacks a discrete edge ( Figs. 33C View Figure 33 , 34C View Figure 34 ). At the anterolateral corner of the choana, the pterygoid has a short medial process that supports the palatine. Th e choanal septum is strut-shaped anteriorly and posteriorly but has an expanded ventral margin centrally. Lenticular fossae are present on either side of a thin median septum. The posterior rim of the choana is sturdy and rod-shaped without any processes. The choanal fossa is invaginated under this rim. The pterygoids extend laterally and posteriorly, so the posterior margin of the palate is deeply U-shaped, unlike the less embayed margin in Anatosuchus ( Figs. 5 View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 ), Araripesuchus (Figs. 14C, 15C), and Mahajangasuchus ( Turner and Buckley 2008) but similar to the deeply embayed posterior margin of the palate in baurusuchids such as Stratiotosuchus .

The ectopterygoid twists into a vertical plane, anteriorly, forming the lateral edge of the suborbital fenestra. Posteriorly, the ectopterygoid extends as the swollen lateral margin of the pterygoid flanges.

The quadrate angles posteroventrally to the jaw articulation in lateral view ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34B View Figure 34 ). Th e condyles are broad and transversely oriented, the lateral condyle larger and more convex. A subcircular fossa is present dorsal to the condyles. A foramen on the medial edge of the fossa just dorsal to the medial condyle is identified as the opening of the siphoneal foramen.

Braincase. The parasphenoid and posterior two thirds of the braincase are not preserved. Th e ventral portion of the basioccipital and basisphenoid are present, their ventral surface inclined anteroventrally at approximately 45°. A low median crest is present on the basioccipital, anterior to which is a large Eustachian foramen. The basisphenoid has limited ventral exposure between the pterygoids and basioccipital, as in Anatosuchus and Araripesuchus . Two crests are present on the basisphenoid to either side of the Eustachian opening ( Figs. 33C View Figure 33 , 34C View Figure 34 ).

Lower jaw. The jaws are shut with prominent crowns fitted snugly into notches in the opposing jaw margin ( Fig. 32 View Figure 32 ). Separation of the jaws would have risked damage to the teeth and alveolar margins. Th e skull was subjected to a computed-tomographic scan to locate small dentary crowns covered from view by the maxilla, and then a cast of the skull was cut apart with hidden teeth restored ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ).

Unlike the sculpted bones of the cranium, most of the external surface of the lower jaw is lightly textured. Only the symphyseal margin and posterior one-quarter of the lower jaws are sculpted.

The dentary is dorsoventrally deep with a nearly vertical lateral surface marked by shallow vertical undulations ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ). Posteriorly, in the region of the coronoid process, the depth of the dentary exceeds that of the dorsal skull roof, as in Mahajangasuchus ( Buckley and Brochu 1999; Turner and Buckley 2008). As in that genus, the prominence of the coronoid process is accommodated by a marked embayment in the jugal. Anteriorly, the symphysis is robust, deep, and angled posteroventrally at approximately 45°. In ventral view, the symphysis is U-shaped. An interdigitating interdentary suture did not allow movement at the symphysis. Th e alveoli of the enlarged caniniform third dentary tooth bulges laterally, as the dentary curves posteriorly. Ventrally, the crypt for the root of this tooth bulges to each side of the symphysis.

Posteriorly, the dentary tapers in depth from the coronoid process. The dentarysurangular suture is L-shaped. It descends vertically from the coronoid process, and then continues horizontally toward the external mandibular fenestra. At the fenestra, the dentary is split into dorsal and ventral rami, which form most of the boundary of this opening ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ). Mahajangasuchus apparently does not have a comparable dentary process ventral to the fenestra. In Anatosuchus and Araripesuchus a short process is present, but it does not border the fenestra ( Figs. 5 View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 , 14, 15). In Kaprosuchus the dentary is a remarkably long element, extending posteriorly to a point nearly ventral to the quadrate cotylus.

A thin medial process of the splenial meets its opposite on the posteroventral edge of the symphysis. At the base of the process lies a large oval foramen between the splenial and dentary. Th e remainder of the splenial contributes to the ventral margin of the lower jaw and forms a thin vertical plate on the medial aspect of the dentary.

The surangular forms the posterior one-half of the coronoid process, from which exits a large anterior surangular foramen. A pointed bone spur, presumably a prominent tendon attachment, is located on the dorsomedial edge of both the left and right surangular. Th e upper one-half of the surangular flares laterally near the glenoid, posterior to which it tapers to the tip of the very long retroarticular process. The surangular forms the lateral portion of the articular cup of the glenoid. Th ere is no articular contact between the surangular and quadratojugal ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ).

The ventral margin of the angular ventral to the external mandibular fenestra is deflected laterally. Th e angular forms the ventral margin of the external mandibular fenestra and extends along the lateral aspect of the hypertrophied retroarticular process. The articular forms the majority of the glenoid and the body of the nearly straight retroarticular process. Th e articular is exposed along the medial aspect of the process and faces dorsomedially, as in Anatosuchus and Araripesuchus . The prearticular sheathes the ventral aspect of the retroarticular process.

Dentition. The dentition of Kaprosuchus is noteworthy for the hypertrophied caniniform teeth in the premaxillae, maxillae and dentaries, which project above and below the skull ( Fig. 32 View Figure 32 ). All exposed crowns are labiolingually compressed and have smooth mesial and distal carinae. Th ere are only three premaxillary teeth. Pm1 is the smallest, its crown rotated laterally so that its lingual crown surface more directly opposes the more laterally situated d1 ( Fig. 36 View Figure 36 ). As a result, the pm1 crowns appear to diverge in anterior view of the premaxilla ( Fig. 36A View Figure 36 ). Th e larger pm2 is rotated in the opposite direction, so that is lingual crown surface is canted posteromedially. Th e carinae on both pm1 and pm2 are displaced lingually, giving these teeth an incisiform shape. The caniniform pm3 is rotated so its lingual crown surface opposes the bend in the mandibular ramus, and the axis of the crown is deflected posteroventrally ( Fig. 36A, B View Figure 36 ). A substantial gape is needed before the tips of opposing premaxillary and anterior dentary caniniforms clear one another ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 ).

There are 10 maxillary teeth in the heterodont right maxillary tooth row, which is completely exposed. The first maxillary tooth projects anteroventrally, canted toward the large dentary caniniform. It is the most slender tooth in the maxillary series. The larger second maxillary tooth projects ventrally and is separated from the third maxillary tooth by a fossa for the fifth dentary tooth. Th e presence of this fossa, is the reason the alveolar margin between m2 and m3 is deeply festooned ( Figs. 33A View Figure 33 , 34A View Figure 34 , 36B View Figure 36 ). The large caniniform m3, which is directed ventrally, is followed by m4, one of the smallest teeth in the series. M4 and m5 straddle a large dentary caniniform, with m4 canted posteroventrally toward that tooth. M6 is transitional in size to m7, the posterior smaller maxillary caniniform, which is directed posteroventrally. M8–10 form a trailing series of increasingly smaller teeth that are directed more strongly posteroventrally.

There are probably 16 dentary teeth. D1–3, d5, and d8 are exposed, and the remaining smaller teeth were visualized in a computed-tomographic scan. The first and second dentary teeth are incisiform only in that their carinae appear to be shifted more strongly lingually. D1 is more than twice the size of d2. Th e fully erupted crown on the right side has a basal diameter of approximately 1 cm and a length of approximately 3 cm, which is subequal to that of caniniform m7. D1, the crown of which is accommodated by a large diameter and deep premaxillary fossa, is regarded here as a caniniform. D3 is the largest dentary caniniform and is canted slightly anterodorsally. D8 is slightly larger than caniniform d1 and is canted slightly posterodorsally.

Revised diagnosis. Mid- to large-sized (̴ 4–8 m) metasuchians with elongate cranial proportions (jaw length from the jaw articulation approximately five times maximum width); U-shaped lower jaws with very gently bowed dentary rami in horizontal and vertical planes; extremely slender dentary ramus (jaw length from the glenoid approximately 30 times depth of jaw at mid-length); dentary ramus with minimum depth at tooth positions d5 and d6; coronoid process transversely broad with horizontal dorsal surface (maximum width approximately 85% maximum height); external mandibular fenestra very reduced or closed; splenial symphysis absent.

Phylogenetic definition. The most inclusive clade containing Stomatosuchus inermis Stromer 1925 but not Notosuchus terrestris Woodward 1896 , Simosuchus clarki Buckley et al. 2000 , Araripesuchus gomesii Price 1959 , Baurusuchus pachecoi Price 1945 , Peirosaurus torminni Price 1955 , Crocodylus niloticus (Laurenti 1768) .

Discussion. In 1925 Stromer described a most unusual crocodyliform from the early Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Bahariya Formation of Egypt ( Stromer 1925). Stomatosuchus inermis has an elongate, flattened “duck-faced” cranium nearly two meters in length, and U-shaped lower jaws that are extremely slender ( Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ). The relatively smooth cranium has dorsally directed orbits situated posteriorly and about 30 relatively small, closely spaced teeth in the anterior one-half of the upper jaw ( Fig. 2A, F View Figure 2 ). Only the alveoli are preserved, which are oval with the larger alveoli averaging about 1.5 cm in maximum length ( Stromer 1925). Posteriorly, the alveoli decrease in size and merge to form a groove at mid-length along the upper jaw ( Stromer 1925; Nopcsa 1926).

The coronoid process of the lower jaw is low and transversely broad ( Fig. 2C View Figure 2 ), and the dentary ramus is straight in dorsal and lateral views ( Fig. 2B, C View Figure 2 ), before the jaw curves abruptly toward the symphysis ( Stromer 1925). Th e symphysis is not preserved, and so there is no evidence to justify later remarks that the symphysis was particularly weak or “moveable” ( Steel 1973). Th e external mandibular fenestra is apparently closed ( Fig. 2B, G View Figure 2 ). Th e retroarticular process is well developed, relatively short, and projects posteriorly. In both medial and dorsal views, the process is subrectangular and does not taper distally.

The holotype and only known specimen of Stomatosuchus was destroyed in World War II, and no additional material of this taxon has ever been discovered. With only the brief accounts by Stromer ( Stromer 1925, 1936) and Nopcsa (1926), the taxon has remained enigmatic. Stomatosuchus is closest in general form to Mourasuchus (= Nettosuchus ), a “nettosuchid” alligatoroid of Miocene age from Columbia ( Langston 1965). Mourasuchus also has an extremely low, “duck-faced” cranium, dorsally facing posteriorly positioned orbits, and extremely slender, U-shaped lower jaws. The lower jaw, furthermore, resembles new stomatosuchid material described below in having a dentary with a festooned alveolar margin and slightly enlarged first dentary tooth. Recent phylogenetic work has confirmed the position of Mourasuchus as a close relative of Purussaurus among alligatorids ( Aguilera et al. 2006).

More detailed comparisons, however, show that Stomatosuchus and Mourasuchus are not closely related and share only general features related to their extreme platyrostral “duck-faced” condition (see Phylogenetic relationships). Th e lower jaws in Stomatosuchus are less strongly bowed transversely and dorsoventrally, the splenial nearly reaches the symphysis rather than terminating near mid-length along the dentary ramus, the coronoid process is very broad transversely rather than only moderately expanded, and the external mandibular fenestra is closed or nearly closed ( Fig. 2B, C View Figure 2 ) rather than large. The posterior end of the lower jaw in Stomatosuchus has a rounded rather than cupped glenoid ( Fig. 2C View Figure 2 ), and the retroarticular process extends directly posteriorly rather than curving dorsally as in Mourasuchus and extant crocodylians ( Fig. 2B View Figure 2 ).

Discovery of new material related to Stomatosuchus provides a long-awaited opportunity to learn more about this enigmatic African taxon. Th e most informative specimen is a mandible from Cenomanian-age beds in a region called Iguidi in Niger (Figs. 1A, 37). Th ese lower jaws were found a short distance from the skull of Kaprosuchus , a contemporary inhabitant of the waterways. A closely related species, known only from anterior dentary fragments, is described from the Cenomanian-age Kem Kem Beds in Morocco (Figs. 1A, B, 42).

| MNN |

Musee National du Niger |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |