Helicopsis, ASACHARACTERISTIC REPRESENTATIVE OF THE, ASACHARACTERISTIC REPRESENTATIVE OF THE

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa156 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5669712 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03A687CE-FFC0-0E70-FF7F-88D1FDBBFDCF |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Helicopsis |

| status |

|

PHYLOGEOGRAPHYOF HELICOPSIS View in CoL View at ENA ASACHARACTERISTIC REPRESENTATIVE OF THE STEPPE FAUNA

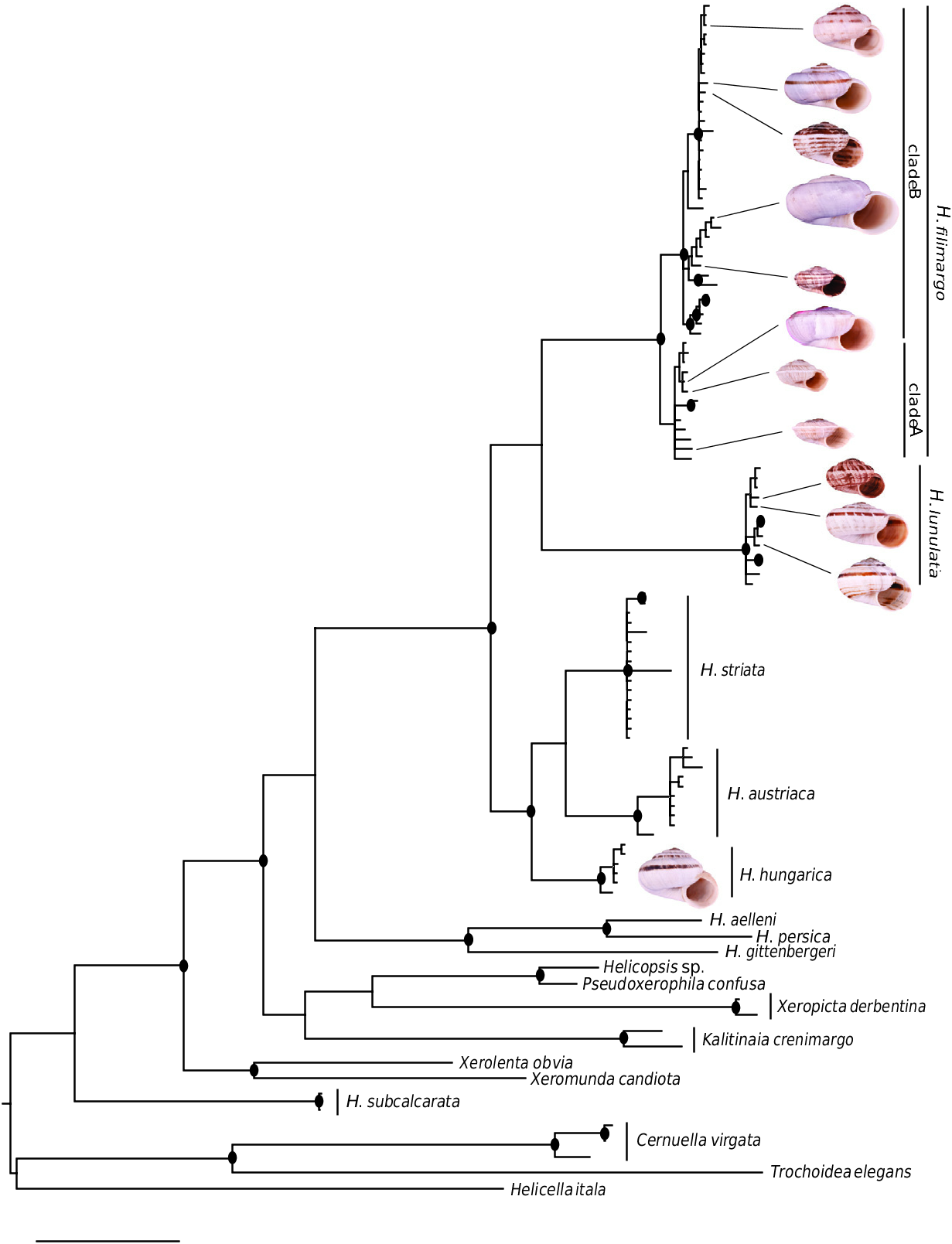

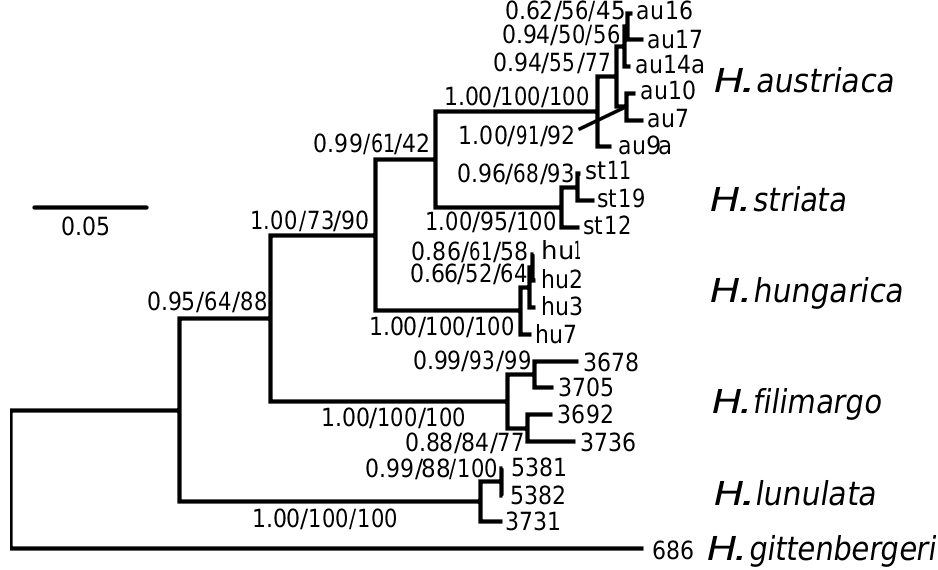

The geographical origin of Helicopsis is unclear. Given that the clade including the Central and Eastern European species is sister to a clade comprising species from Greece and Iran, and the relationships with other genera from the eastern Mediterranean and the Caucasus ( Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ; Supporting Information, Fig. S1 View Figure 1 ), an origin on the Balkan Peninsula is most likely. The nested position of the Central European clade among the Pontic species indicates an eastern origin of the Central European species ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ).

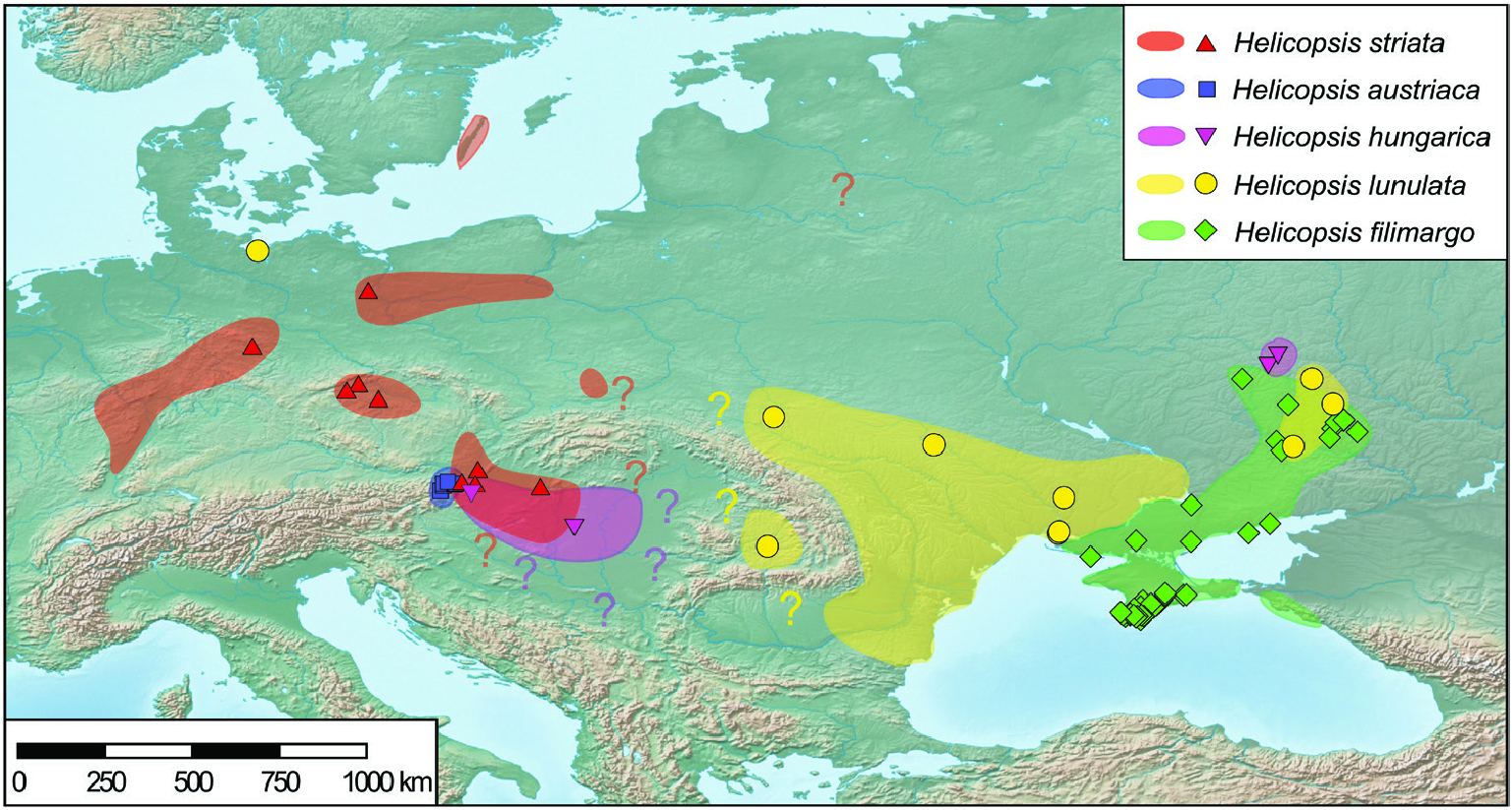

As in many other steppe-inhabiting organisms ( Kajtoch et al., 2016), the differentiation pattern of the Central and Eastern European Helicopsis species reflects the geographic structuring of the steppe belt in Europe in Northern steppes in Central Europe, steppes of the Pannonian Basin and steppes in the Pontic region. Whereas the geographic structure of the steppe belt is reflected in most vagile species at the level of intraspecific lineages ( Kajtoch et al., 2016), the separation of the regions resulted in a differentiation of species in different regions in Helicopsis . With regard to specific differentiation in subregions of the steppe belt, Helicopsis is more similar to subterranean mole rats ( Németh et al., 2013) and southern birch mice ( Cserkész et al., 2016) than to other steppe invertebrates investigated so far.

The Northern steppes in Central Europe and the steppes of the Pannonian Basin are inhabited by the Central European clade including H. hungarica , H. austriaca and H. striata ( Fig. 8 View Figure 8 ). Helicopsis striata is widespread in the Northern steppes, but overlaps with H. hungarica in the north-western Pannonian Basin ( Hudec, 1966; Duda et al., 2018). Helicopsis austriaca is endemic to the eastern fringe of the Alps at the margin of the Pannonian Basin ( Duda et al., 2018). Until recently, H. hungarica was thought to be endemic to the Pannonian Basin. However, Sychev & Snegin (2016) published a mitochondrial sequence of a specimen identified as H. striata from Gubkin in the Belgorod region in the Central Russian Upland, which was identified as H. hungarica by Duda et al. (2018). We here report an additional record of this species from Teleshovka in the Belgorod region. Duda et al. (2018) discussed three scenarios for the origin of H. hungarica . We consider an origin of the species in the Pannonian Basin more likely than in the Central Russian Upland because it forms a well-supported clade with the Central European H. striata and H. austriaca and not with H. filimargo and H. lunulata ( Fig. 2 View Figure 2 ; Supporting Information, Fig. S1 View Figure 1 ), which currently occupy the eastern part of the range of Helicopsis ( Fig. 8 View Figure 8 ). We have not found H. hungarica populations in Ukraine. Thus, the distributional gap between the Pannonian Basin and the Central Russian Upland seems to be real. However, Helicopsis was widespread in central and northern Ukraine in the Pleistocene ( Kunitsa, 2007), where it is currently absent ( Balashov, 2016; Balashov et al., 2018b). Sychev et al. (2015) reported Helicopsis from an almost 3000-year-old soil horizon near Gubkin in the Belgorod region. Thus, it is possible that H. hungarica expanded eastwards during the Pleistocene and later went extinct in the large area between the Pannonian Basin and the Central Russian Upland. However, the fossil shells cannot be reliably identified at the species level and it is also possible that the Pleistocene Helicopsis populations from central and northern Ukraine belonged to H. lunulata and formed the connection between its main range in western and southern Ukraine with the nowadays isolated occurrences in the Donetsk Upland and the Central Russian Upland. An alternative explanation for the isolated occurrence of H. hungarica haplotypes in the Central Russian Upland might be an introduction with mining equipment for the extensive iron-ore quarries near Gubkin. However, this hypothesis does not explain the presence of fossil Helicopsis in that region and the occurrence of the species in natural steppe communities. The specific identity of the specimens from the Central Russian Upland with the Pannonian H. hungarica should be confirmed with non-mitochondrial genetic markers to ensure that the H. hungarica haplotypes are not the result of an introgression. There is no evidence for the final scenario of Duda et al. (2018) that the present distribution of H. hungarica in the Carpathian Basin derives from a hitherto unknown southern refuge. The southern range border of H. hungarica is unknown. It is possible that the species extends southwards into the western Balkan Peninsula. However, there is no necessity to postulate a southern refugium for the survival of the species, given that H. austriaca obviously survived at asimilar latitude.

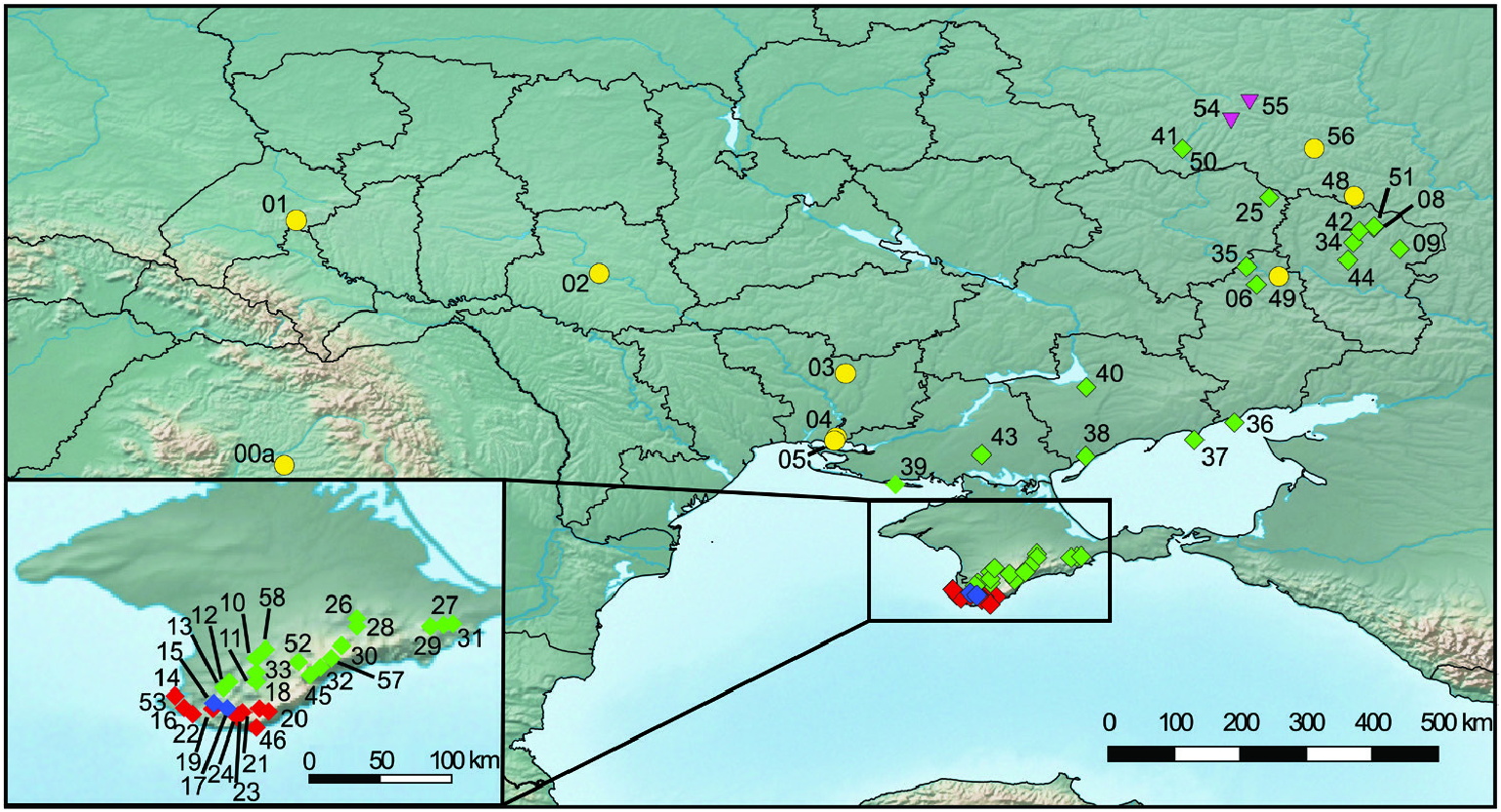

The Pontic region is characterized by H. filimargo and H. lunulata ( Figs 1 View Figure 1 , 8 View Figure 8 ). Helicopsis filimargo is found east of the Dnieper River and especially in Crimea, whereas H. lunulata occupies the part west of the Dnieper. It is not clear whether the isolated populations of H. lunulata in the Donetsk Upland and the adjacent Central Russian Upland are the remains of a formerly continuous range (see above) or whether they are the result of transport by humans. The former hypothesis is supported by the fact that H. lunulata occupies only undisturbed natural steppes in the Donetsk Upland, whereas H. filimargo can occupy transformed habitats. The geographical boundaries of H. striata and H. lunulata are unclear. It has to be checked whether the populations from south-eastern Poland, classified as H. striata ( Stępczak, 2004) , belong to that species or to H. lunulata .

Stewart et al. (2010) suggested that the ranges of some steppe species are currently contracted in interglacial refugia. This is the case for H. striata that was more widespread in Central Europe westwards to England during the glacials ( Jaeckel, 1962; Ložek, 1964), but is currently restricted to some of the Northern steppe fragments and the north-western part of the Pannonian Basin. However, not all steppe species are contracting in the interglacials. This is shown by significantly negative Fu’s F s statistic indicating population expansion in H. filimargo . The highest mitochondrial haplotype diversity, and a high diversity with regard to nuclear AFLP markers, were found in Crimea. Helicopsis filimargo probably originated in Crimea and expanded from there into the Black Sea Lowland and the Donetsk Upland. Fu’s F s statistic was not significant in H. lunulata , which is patchily distributed across Ukraine. However, we cannot exclude that the lack of significance was the result of the small sample size.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |