Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus ( Morawitz, 1867 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4312.2.9 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:E8D56748-C21D-4798-A562-24F4Dc9Cb1C3 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6022346 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03AA084C-6C40-AE73-A899-FB39FBC2FAC9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus ( Morawitz, 1867 ) |

| status |

|

Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus ( Morawitz, 1867) View in CoL

Odynerus magnificus Morawitz 1867: 119 –121, ♀ ( type locality: “Gouvernement von Saratow ” [ Russia]), lectotype (designated here): ♀, “Sarepta” (ZISP); 1895: 454–455, Russia (Sarepta [ Volgograd], Astrakhan), Armenia. Odynerus morawitzi André 1884: 694 –695, ♂ ( type locality: “Sarepta” [ Russia]), lectotype (designated by Gusenleitner 2001: 214) in Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle de Neuchâtel, Switzerland, synonymized by Giordani Soika 1970: 130. Brachyodynerus magnificus: Giordani Soika 1970: 127 View in CoL –128, Russia ( Dagestan), Armenia, Turkey; Tobias & Kurzenko 1978: 170, Russia (south-east of European part); Kurzenko 1981: 104, Russia (Caucasus, Lower Volga Region), West Kazakhstan; Scobiola-Palade 1989: 86, Romania; Aliyeva 2010: 57 –59, Azerbaijan; Fateryga 2010: 78, Russia ( Crimea); Amolin & Artokhin 2014: 12, Russia ( Rostov Prov.).

Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus: van der Vecht & Fischer 1972: 77 View in CoL , SE Europe, SW Asia.

The species can be distinguished from B. quadrimaculatus View in CoL , the second local species of the genus, by having orange with black (not black with whitish) coloration of the body, broader upper lobe of the propodeal valvula separated from the propodeum by a narrow slit (not by broad emargination), and narrower apical margin of the second metasomal tergum.

Material examined. Lectotype (designated here): Volgograd Prov.: Sarepta [Volgograd], 1 ♀, leg. Becker (full labels are the following: “557”, “Сарепта. Беккеръ. [Sarepta. Becker.] 1865”, “ Od. magnificus . Moraw.”, “Lectotypus Odynerus magnificus F. Mor. 1867 . ♂ [sic!] des. N. Kurzenko 1975”) (ZISP); the lectotype was designated by N.V. Kurzenko in his thesis manuscript (1978: 257), but never published. Paralectotype: Astrakhan Prov.: Ryn-Peski, 1 ♀ (ZISP). Additional material: Russia: Volgograd Prov.: Elton Lake, 4.VI.1996, 8 ♂, leg. V. Dubatolov & I. Lyubechansky (ISEN); Sarepta [Volgograd], 1 ♀, 6 ♂, leg. Becker, 2 ♂. Astrakhan Prov.: Astrakhan, 1 ♂, leg. Jacowlew, 4 ♂, 28.V.1915, 1 ♀; Ryn-Peski, 1 ♂ (ZISP). Kalmykia: Yashkul distr., 4 km NE Yashkul, 16.VII.2015, 1 ♀, leg. S. Belokobylskij, V. Loktionov, M. Mokrousov & M. Proshchalykin; Oktyabr’skiy dist., 3 km SSE Tsagan-Nur, 13.VII.2015, 3 ♂, leg. S. Belokobylskij, V. Loktionov, M. Mokrousov & M. Proshchalykin (CFUS). Dagestan: 2 ♂, leg. I. Parfentyev (ZMMU); Tarumovka distr., 9 km SSE Kochubey, 21.VII.2015, 1 ♂, leg. S. Belokobylskij, V. Loktionov, M. Mokrousov & M. Proshchalykin (CFUS). Stavropol Terr.: Neftekumsk distr., Zimnyaya Stavka, 19.VII.1911, 1 ♂, leg. Uvarov (ZISP). Crimea: Razdolnoye distr., Kropotkino, VI–VIII. 1971, 12.IX. 1 971, 2 ♀, leg. S. Ivanov; Razdolnoye distr., Portovoye, 9.IX.2012, 1 ♂, leg. V. Zhidkov; Nizhnegorskiy distr., coast of Sivash Gulf, 3 km S riv. Salgir, 10.VII.2017, 8 ♀, 5 ♂, leg. A. Fateryga; Feodosiya, Barakol Lake, 28.VII.2014, 29.VII.2014, 30.VII.2014, 31.VIII.2014, 2 ♀, 9 ♂, leg. Yu. Budashkin, 13.VIII.2014, 6.IX.2014, 20. VI.2 0 15, 11.VIII.2016, 17.VIII.2016, 21.VI.2017, 8 ♂, leg. A. Fateryga, 26.VIII.2014, 1 ♂, leg. S. Ivanov; Lenino distr., L’vovo, 28.V.2013, 1 ♂, leg. Yu. Budashkin (CFUS); Lenino distr., Zavetnoye, 4.VIII.1972, 1 ♀, leg. Shcheglenko (OSZU). Armenia: Ejmiatsin [Vagharshapat], 2 ♂. Kazakhstan: Mangyshlak Peninsula, 1 ♂ (ZISP).

Distribution. The nominative subspecies occurs in Russia ( Rostov Prov., Volgograd Prov., Astrakhan Prov., Kalmykia, Dagestan, Stavropol Terr., Crimea), Romania, Ukraine, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Kazakhstan. The subspecies Brachyodynerus magnificus luxorius ( Kostylev, 1929a) is known from Armenia and Turkmenistan (Kurzenko 1978); the taxonomic status of B. magnificus luxorius , however, requires further study because both subspecies were collected in Armenia from the same locality (Ejmiatsin [Vagharshapat]).

Remarks. The species is not included to the “Fauna Europaea” database ( Gusenleitner 2013b) because Gusenleitner (2000) thought that the report of Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus from South-East Europe by van der Vecht & Fisher (1972) was based on a misidentification. However, this species was described from European part of Russia and was also reported from Romania ( Scobiola-Palade 1989). There are no published reports of B. magnificus from Ukraine but photos of this species taken in Kirillovka ( Zaporizhzhia Prov.) (http:// macroid.ru/showgallery.php?cat=114735) allow identification without doubts.

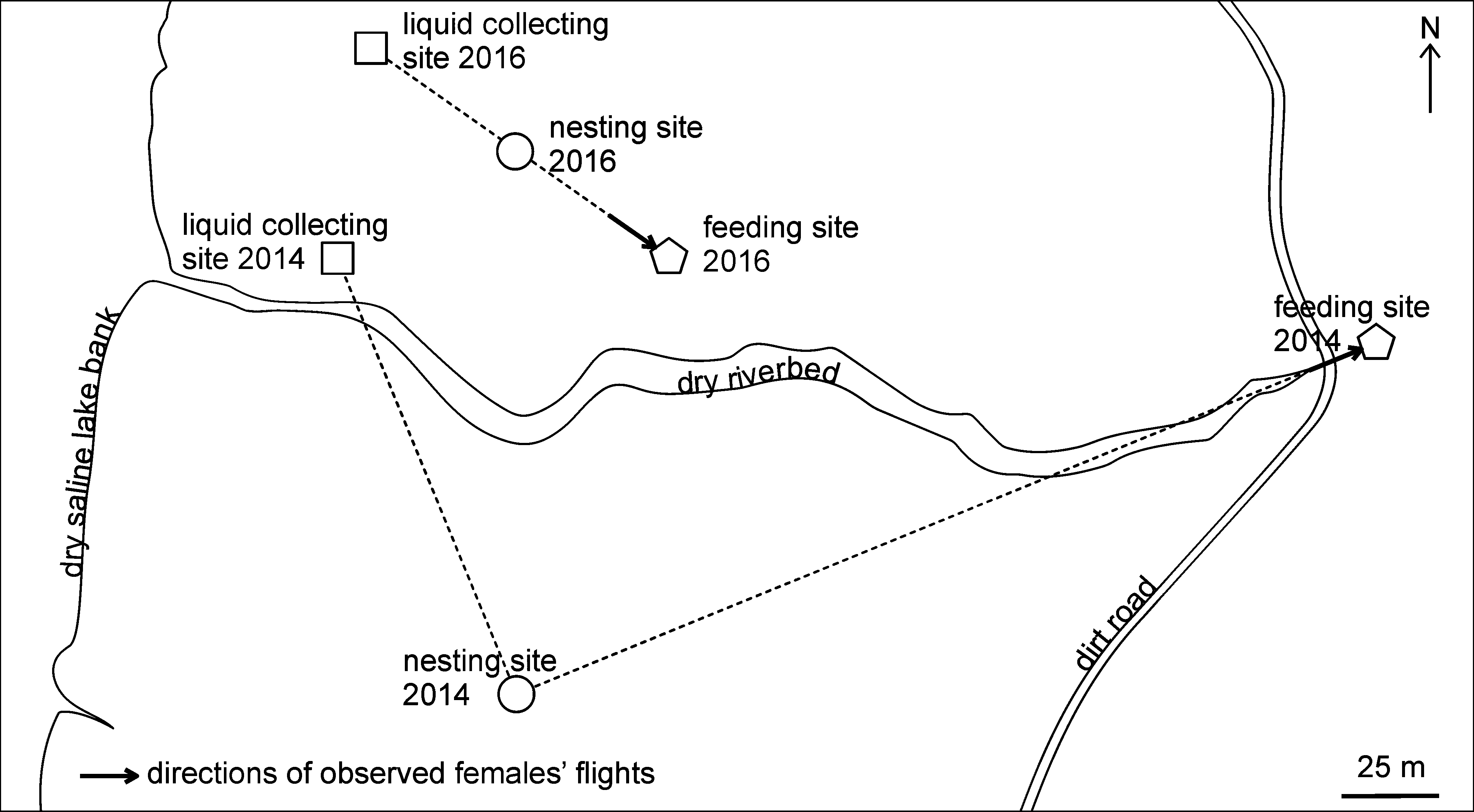

Natural history. Nesting site and substrate. Both sites where the nesting of Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus was observed (in 2014 and 2016) were flat saline lands covered by halophitic vegetation consisting of three plant species: Halimione verrucifera (M. Bieb.) Aellen , Petrosimonia oppositifolia (Pall.) Litv. (Chenopodiaceae) , and Puccinellia fominii Bilyk (Poaceae) ; the general coverage of these herbs was about 75% ( Figs 2–3 View FIGURES 2 – 7 ). Other plant species mentioned below were present only outside of the nesting sites. The soil forming the nesting sites was dense clay loam with some characters of the true clay ( Table 1). This soil was characterized by the presence of a continuous net of cracks, which had variable length, depth, and width.

All studied nests were burrows excavated by females in lateral walls of the soil cracks. Thus, it was difficult to find the nests, because they were not visible from outside; for this reason, only five nests were found. The only possible way to find a nest was to observe a female flying in or out from a soil crack ( Fig. 4 View FIGURES 2 – 7 ). Moreover, it was impossible to recognize the exact position of the nest entrance in two of the five discovered nests, therefore, only three nests were successfully dissected. The exact position of the nest entrance was established in these three nests with the help of light directed into the cracks with a small mirror immediately after the females had entered them. Similar attempts failed in two other cases, probably due to the more complicated structure of those cracks.

Nesting activity. The activity period of the females of Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus observed in August began at 8.20–8.50 and finished at 17.50–18.50 (solar time). Females started their nesting by searching for a suitable nesting site. They made slow zigzag flights several centimeters above the ground level, landed on crack edges, and penetrated each crack to investigate it. This behavior generally took up to several hours, and the investigation of each crack usually took several minutes. Initiation of the nesting was not observed: two dissected nests were initially discovered at the time of the excavation of nest burrows and the third one was observed at the time of its sealing. Females did not visit any open water sources (e.g., a water furrow available not very far from the nesting sites) but used a liquid during the building activity. They obtained this liquid by gnawing the succulent leaves of two halophitic plant species of the family Chenopodiaceae : Suaeda salsa (L.) Pall. ( Fig. 5 View FIGURES 2 – 7 ) and rarely P. oppositifolia . This liquid was regurgitated by them on dry ground surface to moisten it and to make mud pellets during both the excavation of the nest burrow and the sealing of the nest. Females did not make these flights after rain when the ground was moist. Flights for the liquid were made each 3–11 min. during nest construction (usually each 3–5 min.); each flight usually took less than 1 min., but flights for 2–9 min. were also observed. Longer flights were not likely made for liquid alone but for feeding on flowers, as well. A single portion of the liquid was taken from a leaf during 5–10 sec.

Behavior of the females inside nest burrows was not observed due to the location of the nests inside soil cracks. Some building acts, however, were visible from outside. A female excavating the nest burrow retrieved mud pellets from it. She moved backwards and when her back half appeared outside, she immediately dropped the pellet. Thus, all pellets fell on the bottom of the soil crack directly under the nest entrance. There was no entrance turret or any other structure around the entrance of the nest burrow in all observed nests; each entrance was a simple round opening in a lateral wall of the soil crack. The excavation of the nest burrow took 8–10 hours.

The sealing of the nest occurred in the following way. After oviposition and provisioning, the female went out from the nest and moved 2–3 cm from the nest entrance, but still within the soil crack. Then, she regurgitated some liquid on the crack wall surface and made a mud pellet from the moistened ground. After that, she returned into the nest entrance and used this pellet to construct the plugs of the last nest cell and of the nest itself. The sealing of the nest was observed for 75 min. but it could actually have taken more time because our observations may not have started at the beginning of this act.

Hunting. Hunting females were observed at the dry riverbed and directly at the nesting sites. The only prey of Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus were caterpillars of Aporiptura ochroflava (Toll) ( Lepidoptera : Coleophoridae ), which fed on a single plant species, H. verrucifera . Typical of the coleophorid moths, a caterpillar of A. ochroflava makes a case ( Fig. 6 View FIGURES 2 – 7 ). This case is constructed using the epidermis of the host plant leaf. The leaf from which the case was constructed has a visible pale mine on its lamina. Similar mines could be observed on the leaves on which the caterpillars fed. Females of B. magnificus made slow zigzag flights around the plants of H. verrucifera and investigated them. They paid special attention to leaves with mines; when a female noticed such a leaf, she landed and studied it from all sides to find the case with the caterpillar.

Successful hunting was observed two times. Each time a female landed on a leaf and discovered a case of A. ochroflava on its underside. Then, she rapidly took the case with her mouthparts and fore legs and flew about 10 cm from the leaf onto a nearest inflorescence of H. verrucifera . After that, the female began to gnaw a lateral side of the case near its distal end. This act caused the caterpillar to come out from the opened proximal end of the case and the female wasp took it with her mandibles and fore legs. During these acts she held the case with her middle legs; hind legs were used to hold on the inflorescence ( Fig. 7 View FIGURES 2 – 7 ). When the caterpillar had been completely retrieved the female dropped the case, stung the victim several times during 1–2 sec., and flew away. All these acts took less than 1 min. but searching for prey usually took 20–50 min. (rarely up to two hours).

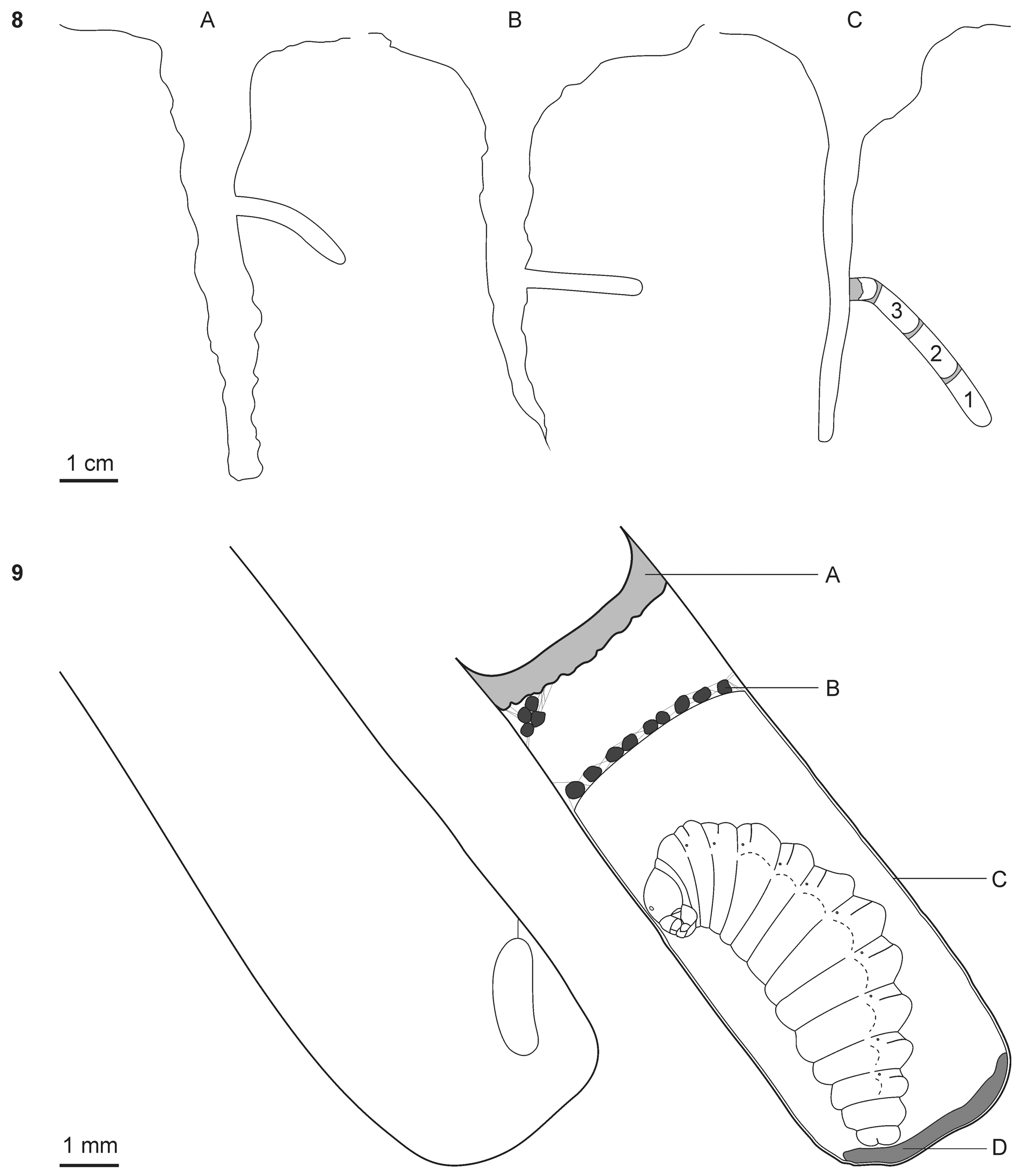

Structure and contents of nests. Three successfully dissected nests were located in the soil cracks 6–7 cm in depth and 0.5–1.5 cm in width; nest entrances were opened at depths of 2.5– 4 cm ( Fig. 8 View FIGURES 8 – 9 ). The entrances were opened northward in one nest and southward in two others. Nest burrows varied from nearly horizontal to strongly inclined; they began horizontally, however, in all three nests. The diameter of the nest burrow was 3–4 mm in different nests. The inner walls of the nest burrows were denser than the surrounding ground due to their tramping by the females; they were smooth but with small transverse wrinkles. Two nests studied in 2014 were abandoned by females ( Fig. 8 View FIGURES 8 – 9 A–B). They were dissected on September 6 at the end of the nesting period of Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus . Both nests had nest burrows 19 mm long. The first nest was empty and the second one contained 15 dried caterpillars of Aporiptura ochroflava stored near the end of the nest burrow. Thus, the nest cell of B. magnificus was not different from other parts of the nest burrow. No eggs were found among the dried contents of the cell.

The third nest studied in 2016 was complete. It was dissected on August 18 immediately after it had been sealed by the female wasp. The nest contained three cells separated by transverse partitions made of mud and was stopped by a thick final plug ( Fig. 8 View FIGURES 8 – 9 C). The nest burrow was 33 mm long and the length of the cells was 8–10 mm.

The final plug was made 2 mm from the last partition and was flush with the lateral wall of the soil crack. The first cell contained a larva of B. magnificus spinning a cocoon. The second one contained a larva of this wasp nearly hatched from the egg and 27 caterpillars of A. ochroflava (one of them had begun to pupate). The third cell contained an egg of B. magnificus and 22 caterpillars. The egg was suspended from the cell ceiling (a wall of the nest burrow) by a filament ( Fig. 9 View FIGURES 8 – 9 ); the size of the egg was 2.0×0.7 mm. The victims were stored in the cells very compactly—there was no empty space in the cells ( Fig. 10 View FIGURES 10 – 15 ).

Two larvae of B. magnificus consumed the caterpillars stored in their cells during 3–4 days. After that, they spun cocoons during 5 days and then discharged meconia onto the bottoms of their cells and became the prepupae. The cocoon had one layer that closely covered the inner walls of the cell, except its 1/5 distal part. It was yellowish, non-transparent, and relatively thick. Prey feces were stored outside the cocoon and secured with few silk filaments. The inner volume of the cocoon slightly exceeded the size of the prepupa. The meconium was located inside the cocoon and was not spread over the lateral walls of the cell ( Fig. 9 View FIGURES 8 – 9 ). After the meconium had been discharged the prepupa fell into a diapause and hibernated ( Fig. 11 View FIGURES 10 – 15 ). Three prepupae from the third nest were obtained; one from the first cell was stored in the ethanol and its development was not observed. The prepupa from the second cell had not pupated before the present paper was submitted but a male emerged from the third cell on June 21, 2017.

Adult feeding. Females and males of Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus fed mainly on flowers of Limonium scoparium (Pall. ex Willd.) Stank. (Plumbaginaceae) , which was the primarily nectar source for this wasp species. The wasps visited mainly freshly opened flowers of this plant ( Fig. 12 View FIGURES 10 – 15 ). They also obtained nectar from faded flowers with the corolla compacted inside the calyx ( Fig. 13 View FIGURES 10 – 15 ). It is interesting that although L. scoparium was abundant around the bank of the Barakol Lake, the wasps feeding on its flowers were observed each year ( 2014 and 2016) only on a few plants concentrated in one local point (the feeding sites on Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ). The second source of nectar important for B. magnificus was flowers of H. verrucifera , but only males were observed on them. Both plant species were in blossom during the second half of summer. The wasps, however, were observed in June and the first half of July as well. Flowers of Achillea nobilis L. ( Asteraceae ) were the main nectar source for B. magnificus at that period and the additional nectar sources were flowers of Teucrium capitatum L. ( Lamiaceae ). A single visit to an extrafloral nectary on an unripe fruit of Ferula caspica M. Bieb. (Apiaceae) by a male wasp was also observed.

Plants visited by B. magnificus for feeding at the coast of the Sivash Gulf were different. Most specimens (both females and males) were recorded there on flowers of Eryngium campestre L. ( Apiaceae ) and on inflorescences of Verbascum phlomoides L. ( Scrophulariaceae ). The wasps did not visit the flowers of the latter species, though. Instead, they took liquid from its sepals, rachis, and bracts ( Fig. 14 View FIGURES 10 – 15 ). The liquid was sucked out through small punctures in the plant epidermis. It was uncertain, however, whether the wasps made those punctures themselves or used punctures made by other species of Hymenoptera , which were abundant and diverse on the inflorescences of V. phlomoides at that site. One female of B. magnificus was also recorded there on flowers of Torilis arvensis (Huds.) Link (Apiaceae) .

Male behavior. Males spent their time feeding on flowers and searching for females at their nesting sites, as well as at the hunting site of the dry riverbed. They made rapid flights around the plant of H. verrucifera at both types of sites and rarely made slow flights above the soil cracks at the nesting sites. Several times males were observed attacking hunting or nesting females, but the latter rejected them. Thus, courtship and copulation were not observed. In the evening (after 18.00) males set on inflorescences of H. verrucifera and began to sleep there ( Fig. 15 View FIGURES 10 – 15 ). Up to three males were observed on a square meter of these plants but more than one male was never observed on one inflorescence. A female sleeping in the manner of males was also observed once.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus ( Morawitz, 1867 )

| Budashkin, Yury I. 2017 |

Brachyodynerus magnificus magnificus : van der Vecht & Fischer 1972 : 77

| Vecht 1972: 77 |

Odynerus magnificus

| Amolin 2014: 12 |

| Aliyeva 2010: 57 |

| Fateryga 2010: 78 |

| Gusenleitner 2001: 214 |

| Scobiola-Palade 1989: 86 |

| Kurzenko 1981: 104 |

| Tobias 1978: 170 |

| Giordani 1970: 130 |

| Giordani 1970: 127 |

| Morawitz 1867: 119 |