Deroplax silphoides (Thunberg, 1783)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4624.3.7 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:FF8F9EB6-99B0-4D7A-B124-8EDA6E40FB41 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03AAAF13-FF9B-1809-0E8C-91A3FE270497 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Deroplax silphoides (Thunberg, 1783) |

| status |

|

Deroplax silphoides (Thunberg, 1783)

( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 )

Cimex silphoides Thunberg, 1783: 29 .

Cimex stigma Fabricius, 1798: 528 .

Odontotarsus coquerelii Signoret, 1861: 918 .

Deroplax silphoides var. stigmata Kirkaldy, 1909: 282 .

Deroplax silphoides var. schoutedeni Kirkaldy, 1909: 282 .

Morphological features. Deroplax silphoides specimens ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 A–D) possess the combination of characters that are characteristic of the subfamily Hoteinae: body ovoid with blackish pattern, metathoracic scent gland with a distinct comma-shaped peritreme, both sexes with sublateral stridulatory vittae on the abdominal sterna.

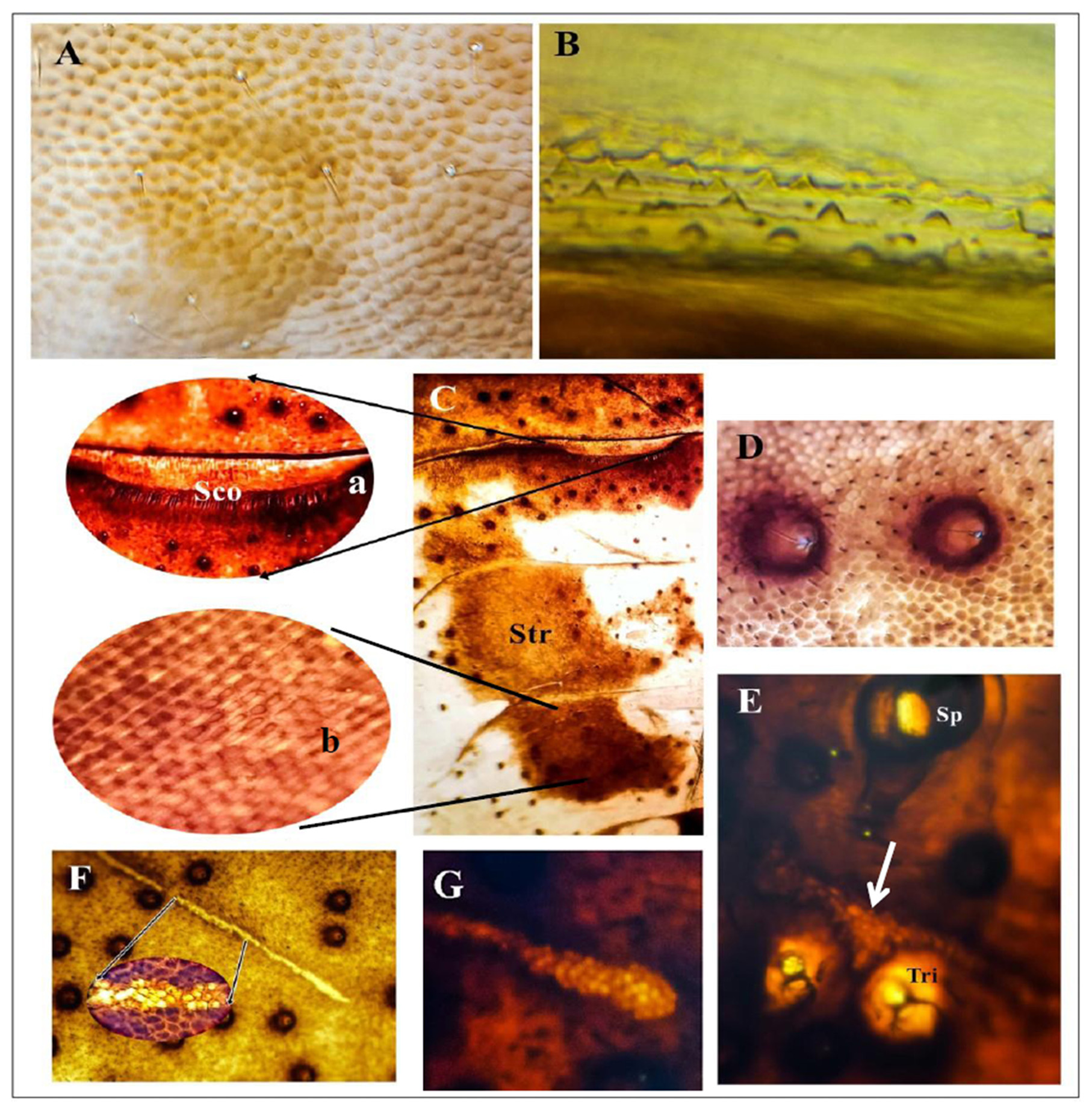

In addition to the morphological features previously mentioned by Leston (1953) and Novoselsky et al. (2015), in the present investigation, we have discovered that the basal third of the scutellum ( Fig. 2A, B View FIGURE 2 ) is depressed in the middle, and it is provided with three prominent transverse grooves. The abdominal terga are characterized by triangular and dome-shaped micro-sculptures ( Fig. 3A, B View FIGURE 3 ); the abdominal sterna are covered with polygonal scalelike micro-sculptures interspersed with minute spines and hairs bearing disks ( Fig. 3D View FIGURE 3 ). Furthermore, the following characteristic feature has been noticed on the abdominal sterna: scent gland openings have been observed in the adults of both sexes as two concave inflections with curved cilia at midline of posterior margin of sternum III ( Fig. 3C, a View FIGURE 3 ). The presence of ventral abdominal glands in males and some females of many groups of Pentatomorpha was reported by Carayon (1981), McDonald & Cassis (1984), Staddon & Edmunds (1991), and Staddon (1999). Many of these glandular systems, especially in males, were considered to be concerned with the production of sex pheromones ( Staddon et al. 1987, Staddon 1990, Aldrich 1996). In our case, the gland may be concerned with aggregative behavior as it found in both sexes. But this needs further research. Sublateral striated patches are present on sterna IV–VI ( Fig. 3C, b View FIGURE 3 ). In addition, special stripe-like structures were observed as a transverse longitudinal golden stripe between each spiracle and trichobothria, stripes on sterna III–VI are long and narrow ( Fig. 3F View FIGURE 3 ) and their bases inserted between the trichobothria ( Fig. 3E View FIGURE 3 ), while shorter and clubbed on sternum VII ( Fig. 3G View FIGURE 3 ) and its base lies above the trichobothria. The presence of specialized cuticular patches on the abdominal sterna was previously recorded in pentatomid bugs by Staddon et al. (1994) who suggested that these patches were an aid to thermoregulation. In our case though, the investigated stripes seem to be correlated with the trichobothria in location, their function needs more studies.

The male aedeagus was previously investigated by Leston (1953) and Carapezza (2009). The aedeagus in specimens examined during the present study ( Fig. 4A, a, b View FIGURE 4 ) agree with the detailed features reported in those two studies. It has two pairs of basally united sclerotized conjunctival processes; the first pair is represented by unequal finger-like extensions with pointed apices; the second pair is biramous, with one arm produced into an elongate filiform extension surpassing the apex of the vesica. The penisfilum is elongate and coiled ( Fig. 4A, b View FIGURE 4 ), and the vesical is dorsoventrally flattened. The parameres ( Fig. 4A, c View FIGURE 4 ) are broadened at the middle with the apical half of the stem provided with long hairs on the outer side, and the preapical region of the crown is characterized by a scaled texture ( Fig. 4A, d View FIGURE 4 ). The female terminalia ( Fig. 4B, a View FIGURE 4 ) has the laterotergites VIII narrow and strongly tapered towards the midline, the laterotergites IX are moderate in size and broadened at the middle. The valvifers VIII are sub-triangular and weakly concave along the outer margins. The female spermatheca ( Fig. 4B, a, b View FIGURE 4 ) is similar to that figured by Carapezza (2009) (Fig. 25 on p. 207), with the receptacle sclerotized, spherical at apex, and connected by a distinct neck-like structure; the receptacle and pumping region has many pores ( Fig. 4B, b View FIGURE 4 ), similar to that found in the scutellerid bug Eurygaster austriaca (Schrank) ( Candan et al. (2011), who also reported that this feature had not been documented for any other scutellerid and pentatomid species). The intermediate part of the pumping region is straight, delimited by two well-developed flanges, the proximal one is more expanded. The unsclerotized zone occupies nearly the entire length of intermediate part. The spermathecal duct is long, convoluted, and without dilation.

Microscopic examination of the egg chorion of D. silphoides revealed that the chorion surface is characterized by a polygonal reticulated pattern ( Fig. 5A View FIGURE 5 ), some of which also have polymorphic granules ( Fig. 5B View FIGURE 5 ). A ring of widely separated aero-micropylar processes was observed on the outer surface of the egg, around its anterior pole ( Fig. 5C View FIGURE 5 ), each aero-micropylar process has a central canal that can be seen on the inner side of the eggshell ( Fig. 5D View FIGURE 5 ). This canal serves for the passage of sperm, and participates in gas exchange in many heteropteran bugs ( Southwood 1956, Cobben 1968). The egg burster can be seen by light microscope as a highly sclerotized blackish-brown triangular configuration connected with a soft median part and ending with a tail ( Fig. 5E View FIGURE 5 ). The egg-burster helps with the breaking of the chorion at the time of hatching ( Southwood 1956). The reticulated pattern of the chorion surface and the remaining of the egg-burster attached to the eggshell were also observed by Candan et al. (2011) in eggs of Eurygaster austriaca . Egg characteristics may have great taxonomic value for the recognition of Heteropteran bugs at the generic level ( Matesco et al. 2009) and perhaps even at the specific level ( Cobben 1968, Suludere et al. 1999).

The specimens studied in this project, however, differ from the D. silphoides specimens that have been examined from other studies in several respects. For example, the sublateral stridulatory vittae was present on sterna IV–VI in the examined specimens while in previous studies, it was observed only on sterna V–VI ( Carapezza 2009, Novoselsky et al. 2015) ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 , p. 7). Also, the penisfilum of the male aedeagus was relatively shorter than the extremely prolonged part illustrated by Carapezza (2009) (Figs. 19, 20, p. 205). Additionally, the female spermathecal had the receptacle spherical at the apex, and connected by a distinct neck, which is longer than in specimens examined by Carapezza (2009) (Fig. 25, p. 207) and Czaja (2016), who mentioned that receptacle of D. silphoides lacked the neck-like structure; the intermediate part of the pumping region is delimited by two well-developed flanges, but Czaja (2016) reported that the distal flange was reduced in their examined specimens.

Material examined: Sharm El Sheikh, South Sinai 15.5.2012 ( 1♀) on Dodonaea viscosa by Robin Bad; El Messaha street, Dokki, Giza 5.5.2016 ( 1♀) by Alaa Hossny; Gamal Abdel Nasser street, 6 th of October City, Giza 10. 5. 2016 ( 1♀) on Chrysanthemum morifolium ; Ain Shams University, Abbassia, Cairo 21.2.2018 ( 1♀) by Shimaa Farag, 5.3.2018 ( 1♂) by Mohamad Nasser, 8.5.2018 (6 nymphs 4 th & 5 th instars), 13. 5. 2018 ( 5♂, 9♀, 11nymphs 3 rd– 5 th instars, 3 egg patches), 30.5.2018 ( 20♂, 23♀, 17 nymphs 3 rd –5 th instars) on Dodonaea viscosa by Sohair Gad Allah & Mohammad Elhawary.

Field observations: Adults and nymphs of D. silphoides were observed in the botanical garden of Ain Shams University in May & June 2018. All specimens were found on Dodonaea viscosa , and it appears that none moved to adjacent ornamental plants, e.g. Duranta variegata Bailey (Verbenaceae) , Ficus nitida Thunb. (Moraceae) , Lantana camara L. ( Verbenaceae ), and Delonix regia (Boj.) (Fabaceae) . Similar to numerous species of scutellerids that are known to exhibit aggregative behavior ( Javahery et al. 2000), adults and second through fifth instar nymphs of D. silphoides were found in mass aggregations amongst dry fruit capsules of Dodonaea viscosa . They fed on the seeds and moved among the branches and leaves. When disturbed, they fell to the ground. In contrast, Novoselsky et al. (2015) reported that the bugs usually remained firmly attached to the plant during a disturbance.

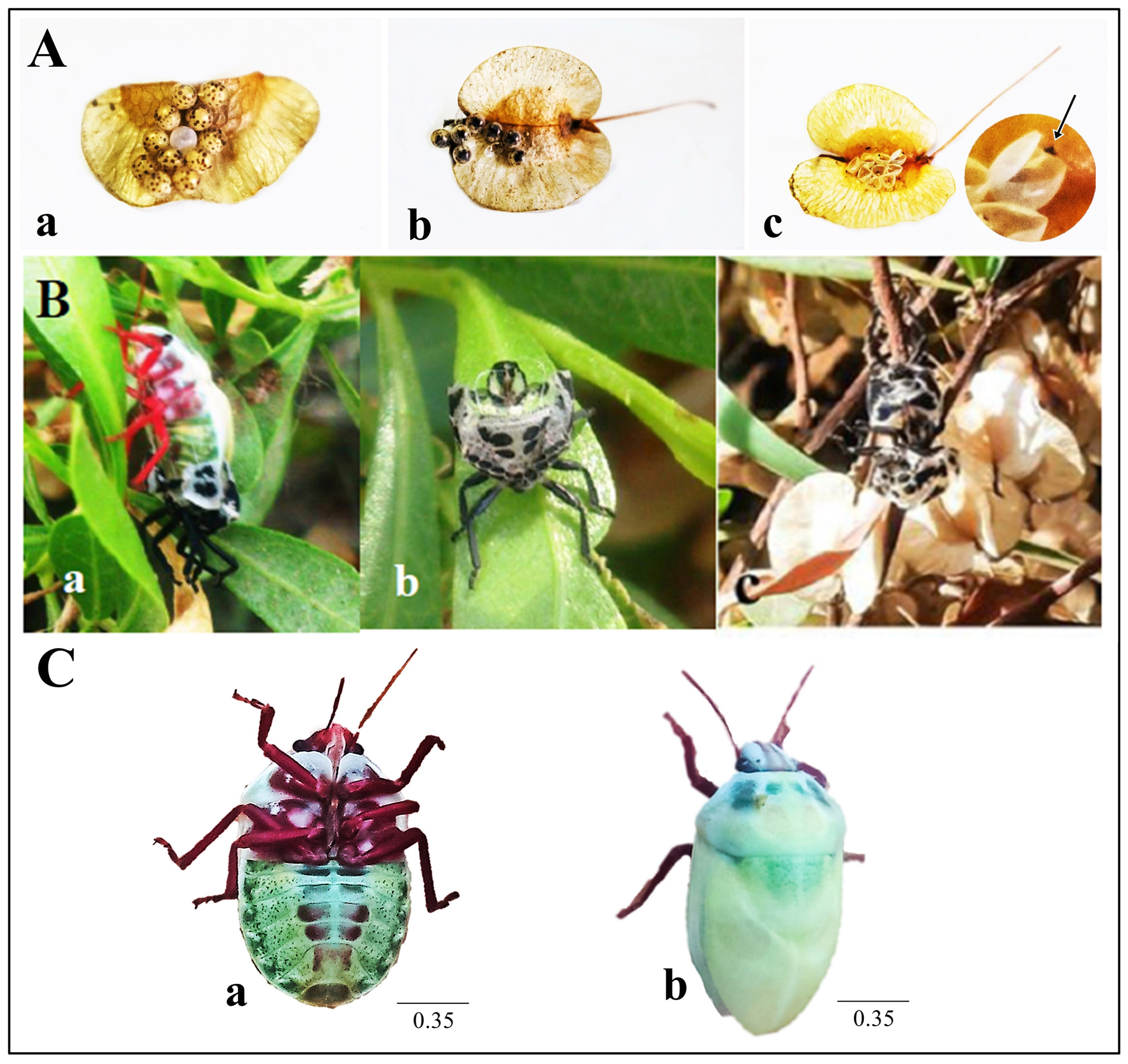

The number of eggs in each egg mass ranged between 9–13, and they were glued onto the fruit capsules of Dodonaea viscosa . Eggs were spherical-shaped; golden yellow with reddish spots ( Fig. 6A, a View FIGURE 6 ); they became darker as the nymphs developed, and they became more transparent at time of hatching which allowed the dark nymph inside to become visible ( Fig. 6A, b View FIGURE 6 ). After hatching, a circular operculum was observed, and the black triangular egg burster was visible, attached to inner side of the empty eggshell ( Fig. 6A, c View FIGURE 6 ).

At each molt, the adults, as well as nymphs, firmly attached themselves to branches or leaves, shed their skins, and left the cast skins behind while they moved to another place on the plant. When we observed the insects at molting time ( Fig. 6B, a View FIGURE 6 ), we found that it emerged through a longitudinal incision along the midline of the pronotum and scutellum with, the help of a transverse incision at base of head. Many exuviae were found with the head separated from the pronotum and slanted forward ( Fig. 6B, b, c View FIGURE 6 ). Both the pronotum and scutellum opened longitudinally along the middle, connected only with the lateral margins of the thorax, while separated from other margins. Newly emerged adults ( Fig. 6C View FIGURE 6 ) have an immaculate light yellowish-green body with red appendages. Their characteristic black pattern on dorsal and ventral sides developed within few hours after molting.

Although the insect is native to a tropical region, based on our observations it can survive up to a week or more at temperatures as low as 2 °C.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Deroplax silphoides (Thunberg, 1783)

| Gadallah, Sohair M., Nasser, Mohamad G., Farag, Shaimaa M., Elhawary, Mohammad O. & Hossny, Alaa 2019 |

Deroplax silphoides var. stigmata

| Kirkaldy 1909: 282 |

Deroplax silphoides var. schoutedeni

| Kirkaldy 1909: 282 |

Odontotarsus coquerelii

| Signoret 1861: 918 |

Cimex stigma

| Fabricius 1798: 528 |

Cimex silphoides

| Thunberg 1783: 29 |