Nyctereutes procyonoides (Gray, 1834)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6331155 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6335045 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03ACCF40-BF2F-FFD1-7E8F-FE39F964D4DF |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Nyctereutes procyonoides |

| status |

|

Raccoon Dog

Nyctereutes procyonoides View in CoL

French: Tanuki / German: Marderhund / Spanish: Perro mapache

Other common names: Tanuki

Taxonomy. Canis procyonoides Gray, 1834 View in CoL ,

Canton, China.

The Raccoon Dog lineage probably diverged from other canids as early as 7-10 million years ago. Some features of the skull resemble those of South American canids, especially the Crab-eating Fox ( Cerdocyon thous ), but genetic studies have revealed that they are not close relatives. Six subspecies are recognized.

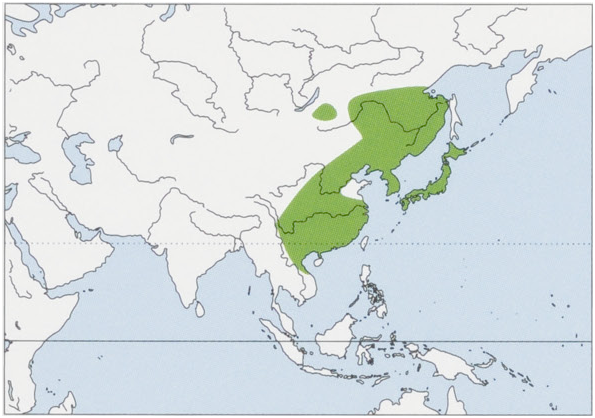

Subspecies and Distribution.

N. p. procyonoides Gray, 1834 — W & SW China and N Indochina.

N. p. albus Hornaday, 1904 — Japan ( Hokkaido).

N. p. koreensis Mori, 1922 — Korean Peninsula.

N. p. orestes Thomas, 1923 — C & S China.

N. p. ussuriensis Matschie, 1907 — NE China, E Mongolia, and SE Russia.

N. p. viverrinus Temminck, 1839 — Japan.

Introduced (ussuriensis) to the Baltic states, Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Moldova, Poland, Romania, W Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Sweden, and Ukraine, occasionally seen in Austria, Bosnia, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, and Switzerland. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 49-2-70- 5 cm for males and 50- 5-69 cm for females, tail 15-23 cm for males and 15-20- 5 cm for females; weight 2:9-12- 4 kg for males and 3-12- 5 kg for females. In autumn and winter, race ussuriensis is very fat and has thick fur, giving an expression of a round animal with short, thin legs. Black facial mask, small rounded ears, and pointed muzzle. Hair is long on cheeks. The body color varies from yellow to gray or reddish, with black hairs on the back and shoulders and also dorsally on the tail. Legs, feet, and chest are dark. Underhair is gray or reddish. The tail is rather short and covered with thick hair. In summer when the fur is thin and fat reserves small, the animal looks much slimmer than in autumn. Dental formula 1s13/3,C1/1, PM 4/4, M 2/3 = 42; M, sometimes missing. Body size of race albus is smaller than that of ussuriensis. Race viverrinus is similar to albus but with somewhat shorter fur, shorter hindlegs, and generally darker color. Skull and teeth are smaller than those of ussuriensis. Mandible width and jaw height for the skull and the lower and upper molars clearly distinguish the two subspecies.

Habitat. Typically found near water, and during autumn, habitat selection appears to be affected by reliance on fruits and berries. In Japan, Raccoon Dog habitat includes deciduous forests, broad-leaved evergreen forests, mixed forests, farmlands, and urban areas from coastal to sub-alpine zones. In the countryside, the species prefers herbaceous habitats and is less likely to use Cryptomeria plantations throughout the year, although riparian areas are often used. In urban environments, Raccoon Dogs inhabit areas with as little as 5% forest cover. In the Russian Far East, they avoid dense forests in favor of open landscapes, especially damp meadows and agricultural land. In the introduced range, Raccoon Dogs favor moist forests and shores ofrivers and lakes, especially in early summer. In late summer and autumn they favor moist heaths with abundant berries. In the Finnish archipelago, however, they prefer barren pine forests, where they feed on crowberries (Empetrum nigrum).

Food and Feeding. Raccoon Dogs are omnivores and seasonal food habits shift as food availability changes. In most areas small rodents form the bulk of their diet in all seasons. Frogs, lizards, invertebrates, insects (including adults and larvae of Orthoptera, Coleoptera, Hemiptera, Diptera, Lepidoptera, Odonata ), and birds and their eggs are also consumed, especially in early summer. Plants are eaten frequently; berries and fruits serve as an important and favored food source in late summer and autumn, when Raccoon Dogs decrease their food intake before entering winter dormancy. Oats, sweet corn, watermelon, and other agriculture products often are found in Raccoon Dog stomachs. Carrion, fish, and crustaceans are consumed when available. As opportunistic generalists, Raccoon Dogs forage by searching close to the ground and may also climb trees for fruits. They mainly forage in pairs, usually wandering some distance from each other.

Activity patterns. Mainly nocturnal, leaving their dens 1-2 hours after sunset. When they have pups, females also forage during the daytime while the male is babysitting. In spring, Raccoon Dogs are also seen during daytime when sunbathing on south-facing slopes ofhills. In areas where winters are harsh they enter a form of hibernation (winter lethargy) in November and become active again in March. The Raccoon Dog is the only canid known to hibernate.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Both males and females defend their home range against individuals of the same sex. Home range size varies according to the abundance of food. The core areas of different pairs are fully exclusive, especially during the breeding season. Peripheral areas of home ranges may overlap to some extent. In autumn there is more overlap than in spring and summer. Different pairs seem to avoid each other even when their home ranges partially overlap. Resting sites may be shared with related family members, and latrine sites may be shared by several individuals. Home range sizes in Russia vary from 0-4- 20 km? (larger ranges in introduced populations in western Russia). In southern Finland, home ranges recorded by radio-tracking ranged from 2-8 to 7 km ®. In Japan, home range size varies from as little as 0-07 km? in an urban setting to 6- 1 km? in a sub-alpine area. Strictly monogamous, the male and female form a permanent pair, sharing a home range and foraging together. Only if one of the pair dies will the remaining member form a new pair bond. Some non-paired adults may stay within the same area and/or share the resting or feeding sites or dens, but usually do not move together. Raccoon Dogs do not bark, but growl when menaced. In Japan their vocalizations are higher in tone than those of a domestic dog and more or less resemble the sounds of a domestic cat.

Breeding. Testosterone levels in males peak in February/March, and progesterone levels in females coincide even with absence of males, suggesting that the species is monoestrous, with seasonal and spontaneous ovulation. Raccoon Dogs reach sexual maturity at 9-11 months and can breed in the first year, but a first-year female will enter estrus more than one month later than older females. Females can reproduce every year. Mating usually occurs in March, and the onset of spring and the length of winter lethargy determine the time of ovulation. Mating occurs in the back-to-back copulatory posture typical of other canids. Gestation period is nine weeks, parturition mostly occurring in May (varies from April to June). The parents settle in a den about a week before the pups are born. Raccoon Dogs will den in old European Badger (Meles meles) setts or fox dens, or alternatively dig their own dens in soft sandy soil. They will also use active Badgersetts, usually together with Badgers. Winter dens usually are located within their home range, but if suitable dens are not available, they may be several kilometers outside the summer home range. Mean litter size varies between four and five in Japan (birth weight approximately 100 g) to nine in Finland and Poland (birth weight about 120 g), and also in the original distribution area in south-eastern Russia. Litter size in north-western Russia is smaller (6-7) on average because of the harsh winters. Litter size is affected by the abundance of wild berries: when berries are abundant, females are in good condition the following spring, and fetal mortality is low and litter sizes are large. At higher latitudes, the young are born later and remain small and slim in late autumn, and may not reproduce the following spring. Therefore, the productivity of the population is lower in areas with long winters compared to areas with milder climates. Pups start emerging from the den at three to four weeks of age and are weaned at about one week later. Both sexes exhibit parental care, taking turns attending the den during the early nursing period. Because the food items of Raccoon Dogs are small, food is not carried to the den. The pups are fed with milk until they start to forage for themselves. The young usually reach adult body size by the first autumn.

Status and Conservation. CITES not listed. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List. In many countries where the Raccoon Dog is hunted legally, hunting is permitted year round (e.g. Sweden, Hungary and Poland). However, in Finland females with pups are protected in May, June, and July, in Belarus hunting is allowed from October to February, and in Mongolia hunting requires a license and is allowed only from October to February. In Japan, hunting and trapping of the species also requires a license or other form of permission and is restricted to a designated hunting season. Species abundance is unknown in the Far East outside ofJapan, where it is considered common. In its European range the species is common to abundant, although rare in Denmark and Sweden. Threats across its range include road kills, persecution, government attitudes, epidemics (scabies, distemper, and rabies), and pollution.

Bibliography. Bannikov (1964), Fukue (1991, 1993), Helle & Kauhala (1995), Ikeda (1982, 1983), Kauhala (1992, 1996), Kauhala & Auniola (2000), Kauhala & Helle (1995), Kauhala & Saeki (2004), Kauhala, Helle & Pietila (1998), Kauhala, Helle & Taskinen (1993), Kauhala, Kaunisto & Helle (1993), Kauhala, Laukkanen & von Rége (1998), Korhonen (1988), Korhonen et al. (1991), Kowalczyk et al. (1999, 2000), Kozlov (1952), Nasimovic & Isakov (1985), Saeki (2001), Ward & Wurster-Hill (1990), Wayne (1993), Yachimori (1997), Yamamoto (1984), Yamsnamoto et al. (1994), Yoshioka et al. (1990).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.