Canis adustus, Sundevall, 1847

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6331155 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6585149 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03ACCF40-BF30-FFC1-7BA7-F8A4FC70D631 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Canis adustus |

| status |

|

Side-striped Jackal

French: Chacal rayé / German: Streifenschakal / Spanish: Chacal rayado

Taxonomy. Canis adustus Sundevall, 1847 View in CoL ,

South Africa.

Concensus is lacking regarding number of subspecies, variously given as between three and seven. Many authorities have pointed out that, as with the Black-backed Jackal, subspecies are hard to distinguish, and the differences may be a consequence of individual variation.

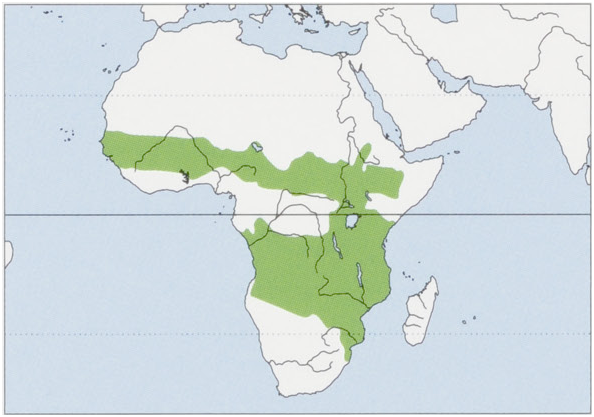

Distribution. W, C and S Africa; replaced in the arid SW and NW of the continent by the Black-backed Jackal and in N Africa by the Golden Jackal. View Figure

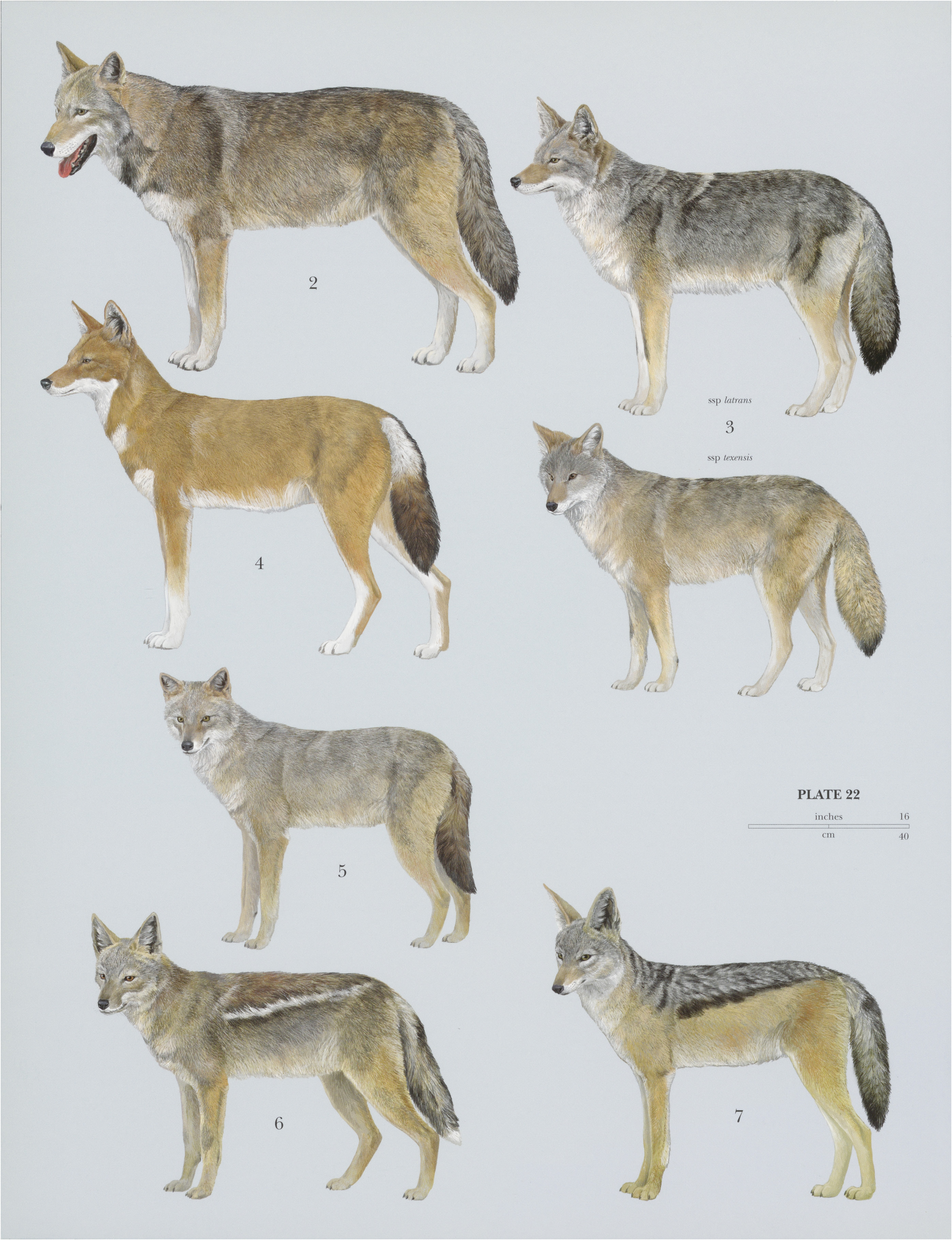

Descriptive notes. Head-body 65-5-77-5 cm for males and 69-76 cm for females, tail 30- 5-39 cm for males and 31-41 cm for females; weight 7- 3-12 kg for males and 7-3-10 kg for females. Medium-sized canid, overall gray to buff-gray in color, with a white side stripe blazed on the flanks, and a diagnostic white tip to the tail. Head is gray-bufty, ears dark buffy. The back is gray, darker than the underside, and the flanks are marked by the indistinct white stripes running from elbow to hip, with black lower margins. The boldness of markings, in particular the side stripes, varies greatly among individuals; those ofjuveniles are less well defined than those of adults. The legs are often rufous-tinged, and the predominantly black tail nearly always bears the distinctive white tip, possibly a “badge” of the species’ nocturnal status. The female has two pairs of inguinalteats. Skull flatter than that of Black-backed Jackal, with a longer and narrower rostrum, a distinct sagittal crest, and zygomatic arches of lighter build. As a result of the elongation of the rostrum, the third upper premolar lies almost in line with the others and not at an angle as in the Black-backed Jackal. The dental formula is13/3,C1/1,PM 4/4, M2/3=42.

Habitat. Occupies a range of habitats, including broad-leaved savannah zones, wooded habitats, bush, grassland, marshes, montane habitats up to 2700 m, abandoned cultivation and farms. Tends to avoid open savannah, thickly wooded areas, and arid zones, but does enter the equatorial forest belt in the wake of human settlement. Side-striped Jackals frequently occur near rural dwellings and farm buildings, and penetrate suburban and urban areas. Where Side-striped Jackals occur sympatrically with Golden and Black-backed Jackals, they may avoid competition by ecological segregation. In such areas of sympatry, Side-striped Jackals usually occupy areas of denser vegetation, and Black-backed and Golden Jackals dominate in the more open areas.

Food and Feeding. Omnivorous, with a diet that is responsive to both seasonal and local variation in food availability. On commercial farmland in the Zimbabwe highveld, they eat mainly wild fruit (30%) and small (less than 1 kg) to medium-sized (more than 1 kg) mammals (27% and 23%, respectively). The remainder of their diet comprises birds, invertebrates, cattle cake, grass, and carrion. In wildlife areas of western Zimbabwe, Side-stripedJackals feed largely on invertebrates during the wet season and small mammals up to the size of Spring hares (Pedetes capensis) during the dry months of the year. They scavenge extensively from safari camp rubbish dumps and occasionally from large carnivore kills (although they are often out-competed for this resource by Black-backed Jackals). In the Ngorongoro Crater, Side-striped Jackals have been recorded competing with Black-backed Jackals for Grant's Gazelle (Nanger granti) fawns. Their diet may consist exclusively of certain fruits when in season. Apparently less predatory than other jackals, although according to one authority this may not hold when prey is highly available. The species forages solitarily, although in western Zimbabwe family groups have been observed feeding together on abundant resources, and as many as twelve have been counted at kills or scavenging offal outside towns. Jackals have been described foraging opportunistically, exploiting food-rich habitats by random walks, and they display an amazing ability to find food where none seems obvious to the human observer.

Activity patterns. Primarily nocturnal, but can employ extremely flexible foraging strategies in areas where they are persecuted. May also adapt activity pattern to reduce competition when in sympatry with Black-backed Jackals.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Side-striped Jackals occur solitarily, in pairs and in family groups of up to seven individuals. The basis of the family unit is the mated pair, which has been known to be stable over several years. In game areas of western Zimbabwe, home ranges varied seasonally from 0-2 km? (hot dry season) to 1-2 km?* (cold dry season), whereas in highveld farmland, home ranges were seasonally stable and in excess of 4 km? (a third of the yearly total range). Sub-adults disperse from the natal territory, up to 12 km in Zimbabwe's highveld farmland and 20 km in game areas. In highveld farmland, territories are configured to encompass patches of grassland where resources are most available, and the structure of the habitat mosaic appears an important factor. Home ranges overlap by about 20% in highveld farmland and 33% in game areas. The residents use the core territory almost exclusively. Vocal repertoire is broad, including an explosive bark, growls, yaps, cackles, whines, screams, a croaking distress call, and a hooting howl. Calling occurs all year round, but is especially common between pair members during the mating period. Jackals from neighboring territories sometimes answer each other. Captive pups have been heard calling at eight weeks, but may start earlier.

Breeding. In Zimbabwe, mating occurs mostly during June and July, and the gestation period is about 60 days. Litters of 4-6 pups are born from August to November, coinciding with the onset of the rainy season. Pup mortality is thought to be high. Abandoned Aardvark (Orycteropus afer) holes or excavated termitaria are common den sites, with the den chamber occurring 0-75— 1 m below the surface and 2-3 m from the entrance. The same pair may use such dens in consecutive years. After the pups are weaned, both parents assist in rearing them, returning at two- to three-hour intervals through the night to feed the pups on food that is probably regurgitated. The pups are aggressive towards each other, as evidenced by the degree of wounding observed. Yearold offspring remain in the parental territory while additional offspring are raised. It appears likely that alloparental care as observed in other jackals also occurs in this species, which may be more social than previously thought.

Status and Conservation. CITES notlisted. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. No legal protection outside protected areas. Regional estimates of population abundance are not available, but from work undertaken in two diverse habitats in Zimbabwe, it seems reasonable to assume the species is common and to estimate a total population in excess of three million. The species appears well capable of exploiting urban and suburban habitats, a factor which may help to ensure its persistence. It is likely that the population is at least stable. Side-striped Jackals are persecuted because of their role in rabies transmission and their putative role as stock killers. In areas of high human population density, snaring may be the commonest cause of death in adult jackals. It is unlikely that this persecution has an effect on the overall population, but indiscriminate culling through poisoning could affect local abundance. The species’ dietary flexibility and ability to co-exist with humans on the periphery of settlements and towns suggests that populations are only vulnerable in cases of extreme habitat modification or intense disease epidemics.

Bibliography. Atkinson (1997a, 1997b), Atkinson & Loveridge (2004), Atkinson, Macdonald & Kamizola (2002), Atkinson, Rhodes et al. (2002), Estes (1991), Fuller et al. (1989), Kingdon (1997), Loveridge (1999), Loveridge & Macdonald (2001, 2002, 2003), Moehlman (1979, 1989), Rowe-Rowe (1992b), Skinner & Smithers (1990), Smithers (1971, 1983), Smithers & Wilson (1979), Stuart & Stuart (1988).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.