PROVIVERRINAE

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12155 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B0878A-D140-A609-FF38-F924C3A6F959 |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

PROVIVERRINAE |

| status |

|

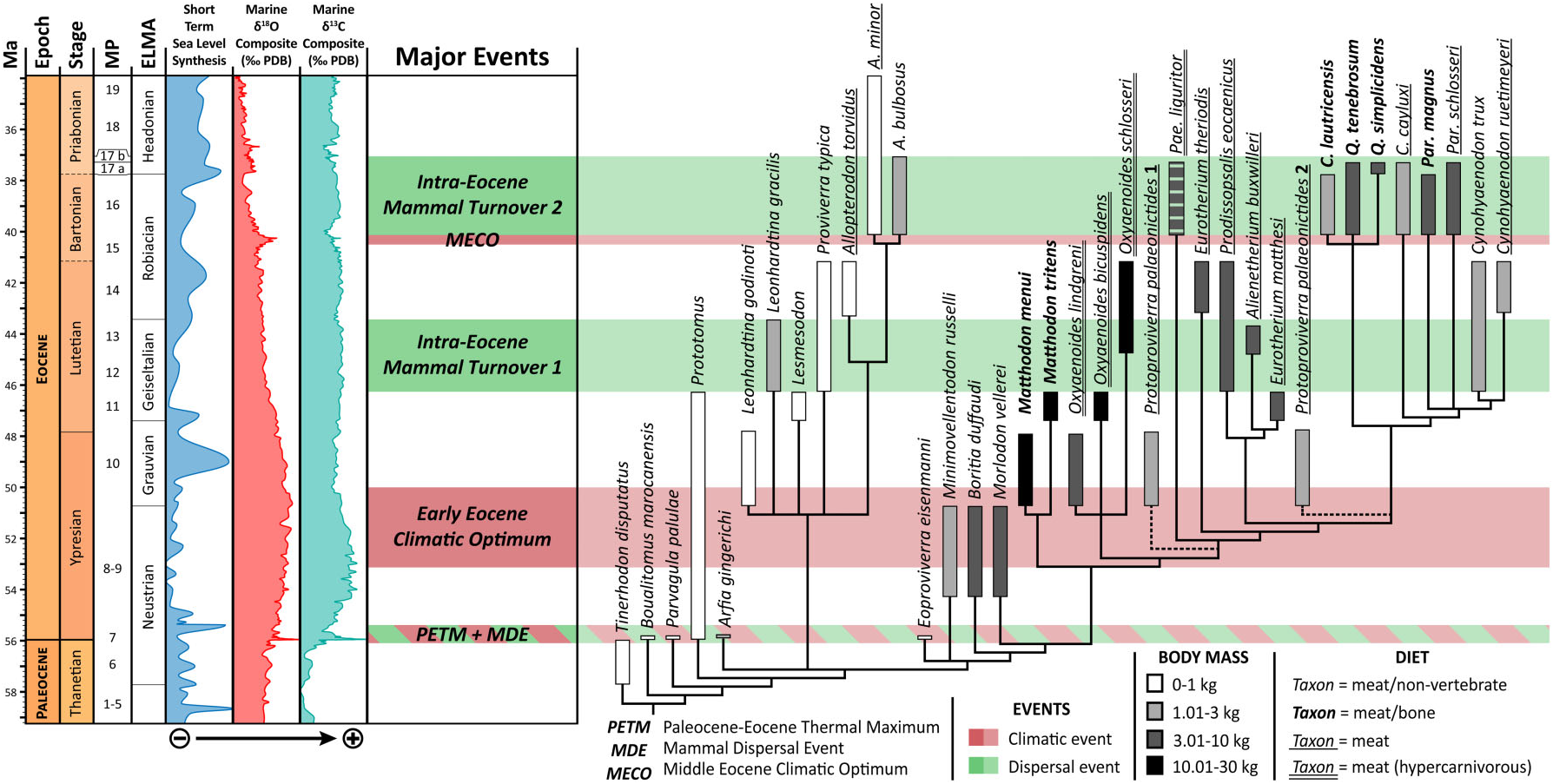

CONVERGENCES AMONGST PROVIVERRINAE

The Proviverrinae lived almost 20 Myr in Europe , where they were the top mammalian predators. Although shortlived, they still succeeded in occupying a wide array of ecological niches over the course of the Eocene , with a great diversity of body masses and ecologies. Even so, it is not surprising that some of the anatomical features displayed by proviverrines are convergences. Two types of dietary-related convergence can be distinguished here: some are adaptations towards hypercarnivory and others towards durophagy .

Hypercarnivorous mammals display very sectorial teeth, which are generally characterized by the reduction to loss of the metaconid on the molars. This type of diet appeared twice in the Proviverrinae , in the Early−Middle Eocene Oxyaenoides and in the Late Eocene Paenoxyaenoides ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ). The dental structures of these two genera are remarkably similar, although they belong to two different clades: Paenoxyaenoides differs from Oxyaenoides in having a wide talonid bearing three cusps, as in some of its relatives (e.g. Eurotherium and Prodissopsalis ). Van Valkenburgh, Wang & Damuth (2004) noted that the evolution of large size in carnivores is generally associated with a dietary shift to hypercarnivory and a decline in species’ durations because of an increased vulnerability to extinction. Moreover, as observed by Holliday & Steppan (2004), hypercarnivores are more limited in subsequent morphological evolution than are less specialized forms, given that evolutionary reversals seem unlikely (= Dollo’s law). The replacement of Oxyaenoides by Paenoxyaenoides thus agrees with the observations of Van Valkenburgh et al. (2004) and Holliday & Steppan (2004).

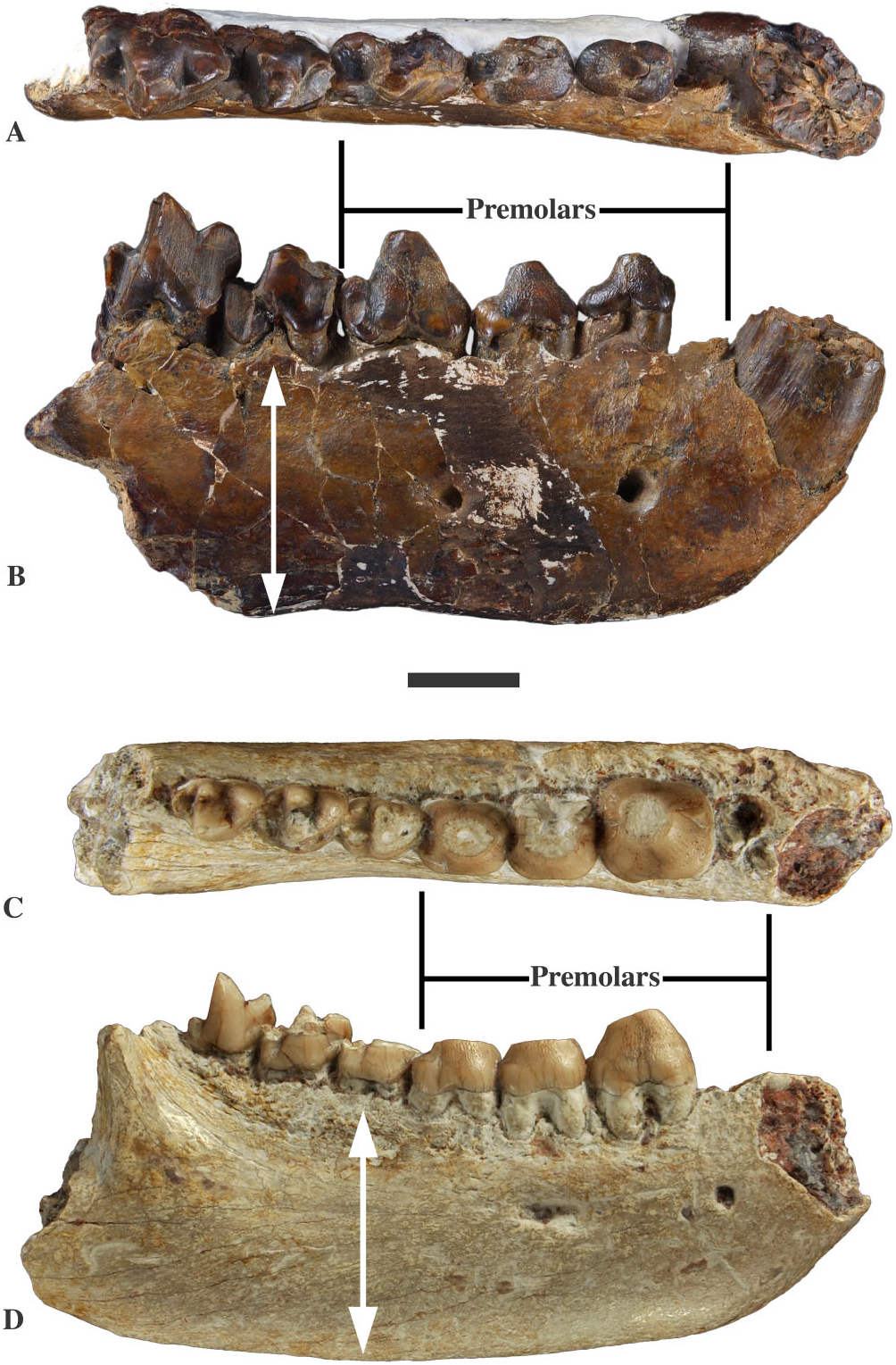

Durophagy is exemplified in proviverrines by Matthodon (Early to Middle Eocene) and Quercytherium (Late Eocene) ( Figs 10 View Figure 10 , 13 View Figure 13 ). As usually observed in bonecracking predators, the two genera have a very high mandible and large premolars. Matthodon differs from Quercytherium in having larger molars lacking a metaconid, and thus in being hypercarnivorous as well, whereas Quercytherium displays very large P 2 and P 3 ( Fig. 13 View Figure 13 ). These differences clearly support independent adaptation towards durophagy.

The repeated, independent evolution of similar feeding morphologies in distinct clades has been often observed in carnivorous mammal groups. The case of the Proviverrinae is interesting because these independent acquisitions occurred in a short time (∼20 Myr). As noted by Van Valkenburgh (1999: 488), ‘there are a fairly limited number of ways to hunt, kill, and consume prey, and consequently, sympatric predators have tended to diverge along the same lines, no matter where or when they lived’. Van Valkenburgh (1999) discussed two hypothetical examples for explaining the replacement of one clade by a second one: ‘active/ competitive displacement’ or ‘passive replacement’ ( Benton, 1987). Concerning the Proviverrinae , the rise of the second clade overlaps the fall of the first clade in time and space; the taxa closely related to Paenoxyaenoides and Quercytherium are contemporaneous with Oxyaenoides and Matthodon ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ). Thus, competition as causal agent seems to have been involved in the evolution of proviverrines, in addition to replacement, as discussed above.

Phylogenetic increase in body size over time, or Cope’s rule, is a common phenomenon in mammals. This phenomenon was discussed for carnivorous clades by Van Valkenburgh (2007). Body mass tended to increase in the Proviverrinae during the Eocene. The largest sizes evolved several times independently, in Oxyaenoides , Matthodon , Paenoxyaenoides , and Quercytherium .

Surprisingly, the genus Allopterodon distinguishes itself by a small increase in body mass: A. bulbosus is only slightly heavier than 1 kg ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ). Lange-Badré & Mathis (1992) also remarked on the stability of the dentition of the species of Allopterodon . However, it is worth noting that A. bulbosus differs in having enlarged premolars ( Lange-Badré, 1979). This genus conserved a more generalized morphology. As noted by Van Valkenburgh (1999), the smallest and more omnivorous carnivorous mammals are also those that are the least specialized, a characteristic that might favour persistence when environments change. Moreover, levels of interspecific competition are not likely to be as high as they are within the large predator guilds. The dental conservatism and small size of the species of Allopterodon may explain its survival up to the very end of the Eocene as the last of the Proviverrinae . Furthermore, as indicated above, the species of the Allopterodon clade differ from their proviverrine contemporaries of the Cynohyaenodon clade in their clearly less sectorial dentition and frequently also in their smaller size. Indeed, in the Allopterodon clade, the fact that the prefossid remained closed conferred a more puncturing function on the trigonid. The species of this clade also differ in having a narrow mandible and straight coronoid crest, in contrast to the condition seen in other proviverrines, in which the coronoid crest is generally distally tilted at an angle of 120°, vs. 100° in Allopterodon . The peculiar morphologies of the dentition and mandible of the species of Allopterodon are reminiscent of those of insectivorous bats (see Smith et al., 2007: fig. 1). It is therefore quite possible that Allopterodon fed mostly on nonvertebrates such as arthropods, unlike the contemporaneous Paracynohyaenodon and Cynohyaenodon . The peculiar features and ecological niche would have limited the size increase of Allopterodon . In any case, it is reasonable to think that it was the arrival of potential competitors, small carnivorans, in Europe since MP18 that brought the last proviverrine to extinction.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.