Esmaeilius, Freyhof & Yoğurtçuoğlu, 2020

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4810.3.2 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:7F0D8427-C06F-4E2B-AE47-13D3654CB286 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B187D4-DF09-FF8D-FF4F-6685FB35DB0A |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Esmaeilius |

| status |

gen. nov. |

Esmaeilius , new genus

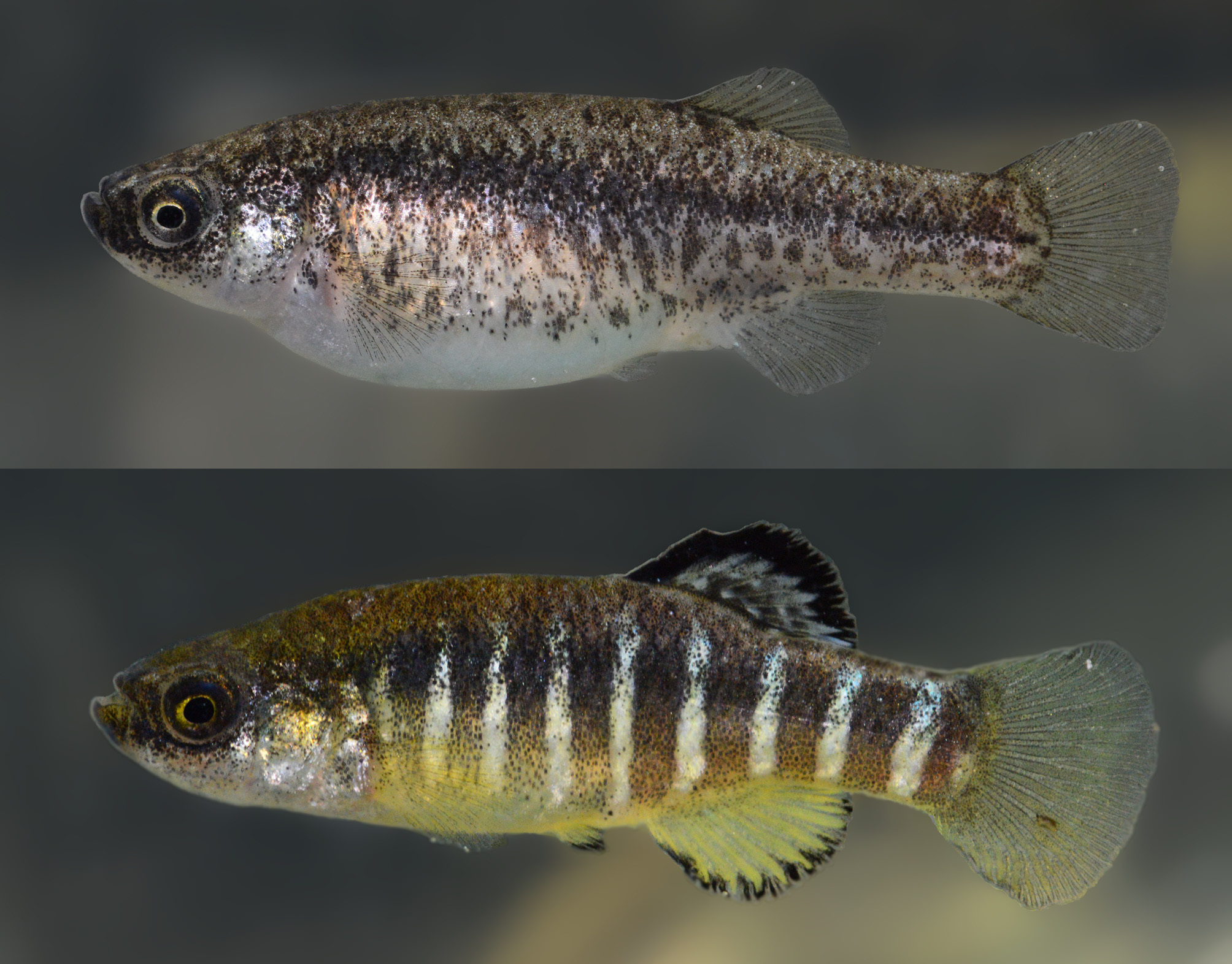

Fig. 16–17 View FIGURE 16 View FIGURE 17

Type species. Lebias sophiae Heckel, 1847 .

Diagnosis. Esmaeilius is distinguished from Anatolichthys and Apricaphanius by possession of a hyaline caudal fin, with a white margin in some species, without bars or rows of spots, or with 1–5 indistinct vertical rows of small brown spots usually restricted to the proximal portion in E. sophiae , (vs. caudal fin with 1–4 bold black or brown bars, or 4–14 vertical rows of small brown spots in Anatolichthys villwocki ), plus a white dorsal- and often caudal- and anal-fin margins in the male, except E. isfahanensis which possesses black dorsal- and anal-fin margins (vs. dorsal and anal-fin margins black, caudal-fin margin hyaline).

Esmaeilius is distinguished from other genera in the family Aphaniidae by the following combination of nonunique characters: head canals absent (vs. present in Aphanius and Aphaniops ); dermal sheath at the anal-fin base in the nuptial female present (vs. absent in Aphaniops ); a single row of tricuspid teeth (vs. three rows of conical teeth in Kosswigichthys ); body covered by scales (vs. naked in Kosswigichthys ); pelvic fin present (vs. absent in Tellia ); flank pattern in male comprising a series of black or brown bars (vs. small whitish or blue spots arranged in vertical series or very narrow bars in Paraphanius); a bold black spot at centre of the caudal-fin base in female present (vs. absent in Paraphanius); dorsal- and anal-fin margin white or black in male (vs. without white or black margins in all Aphaniops except A. sirhani , yellow in Tellia , only dorsal-fin margin black in Aphanius ); background colour of caudal fin identical to interspaces between flank bars (vs. caudal fin pale or deep yellow or orange, distinct from silvery interspaces between flank bars in Aphanius ).

Included species. Esmaeilius sophiae , E. darabensis , E. isfahanensis , E. persicus , E. shirini , E. vladykovi .

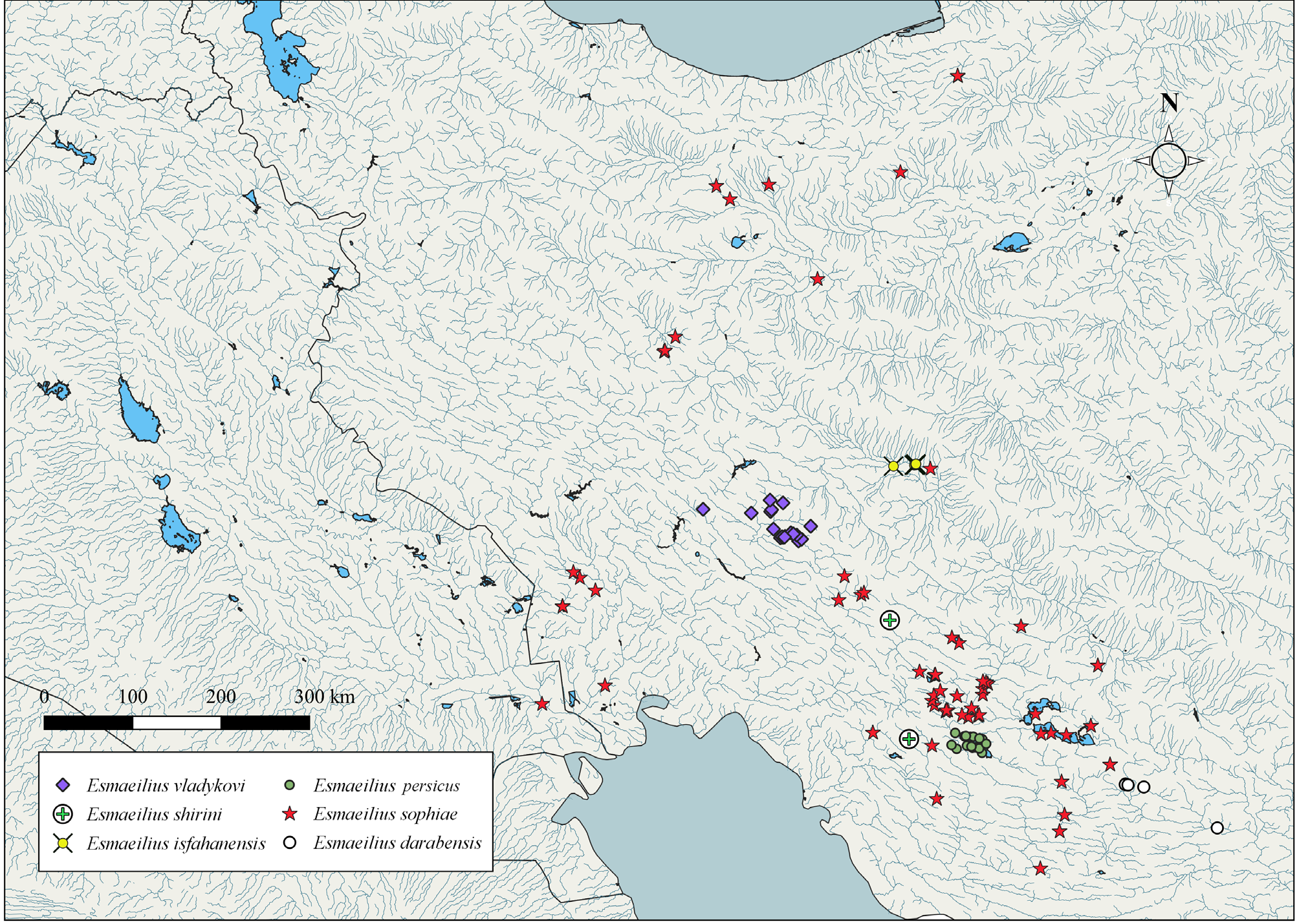

Distribution. Esmaeilius species are widespread in inland waters of Iran and the lower Shat-al-Arab River drainage in Iraq ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 ). Esmaeili et al. (2020) provided a detailed map showing the distribution of the genus.

Etymology. Named for Hamid Reza Esmaeili (Shiraz) for his extensive contribution to the understanding of diversity within this genus. Gender masculine.

Remarks. Esmaeilius is distinguished from Anatolichthys and Apricaphanius by colour pattern, specifically the absence of bars in the caudal fin (vs. presence of bars in all species except A. villwocki ) and presence of white (vs. black) dorsal- and usually caudal- and anal-fin margins in all species except E. isfahanensis . This combination of characters never occurs in Anatolichthys or Apricaphanius species.

Anatolichthys villwocki is similar to E. sophiae in possessing rows of small brown spots in the caudal fin but it differs by possessing black (vs. white) dorsal- and anal-fin margins. Esmaeilius isfahanensis is similar to Anatolichthys and Apricaphanius species in possessing black dorsal- and anal-fin margins but it differs by lacking bold black bars in the caudal fin.

Brachylebias persicus Priem, 1908 was transferred to Aphanius by Gaudant (2011), becoming a senior secondary homonym of Cyprinodon persicus Jenkins, 1910 (= Aphanius persicus ), and Aphanius farsicus was proposed as the replacement name by Teimori et al. (2011). When the phylogenetic groups of Aphanius are separated into different genera, Brachylebias must be considered as incertae sedis as we find no arguments to place it in one of the genera recognised here and it may represent a distinct (extinct) evolutionary lineage. Brachylebias , Aphaniops and Aphanius share the presence of a preopercular canal ( Gaudant (2011), and therefore B. persicus might have been a Miocene species of Aphaniops or Aphanius (see Discussion below). While there is a need to re-examine the materials of Brachylebias , we currently find it highly unlikely that Brachylebias might have been a species of Esmaeilius .

Brachylebias persicus and Cyprinodon persicus became secondary homonyms when both were placed in Aphanius . Because the two names are no longer congeneric, and because the replacement name was raised after 1960, the older name Cyprinodon persicus Jenkins must be reinstated as the valid name ( ICZN 1999: Art. 59.4). This makes Aphanius farsicus a junior synonym of Cyprinodon persicus .

The molecular phylogeny and results of four different molecular species delimitation methods published by Esmaeili et al. (2020) strongly suggest that an excessive number of Esmaeilius populations have been recognised as species. Esmaeilius darabensis , E. persicus , E. isfahanensis , E. shirini , and E. vladykovi were supported by all four methods, but E. arakensis is only supported by two methods while E. pluristriatus is paraphyletic with only a single population supported by one method. Teimori et al. (2012), Esmaeili et al. (2012), Gholami et al. (2014), and Esmaeili et al. (2014a, b) find it difficult to clearly distinguish E. arakensis , E. kavirensis , E. mesopotamicus , and E. pluristriatus from E. sophiae by morphology and used a series of vague or overlapping character states, while there is little molecular distance between them. Gholami et al. (2013) recognised that geographic isolation of these species might have occurred in the Holocene, thus explaining the minor molecular differences. We recognise all four of these nominal species as populations of E. sophiae because they have largely been diagnosed by otolith shape, a character likely to vary between individual populations in the family Aphaniidae ( Schulz-Mirbach et al. 2006, Reichenbacher et al. 2009 a, Annabi et al. 2013). The same might be true for scale surface microstructure as suggested by Gholami et al. (2013). We see no reason to treat E. arakensis , E. kavirensis , E. mesopotamicus , and E. pluristriatus as distinct species and therefore, we synonymise them with E. sophiae .

It must be noted that we fully support distinguishing species with little or no molecular separation, provided they can be clearly distinguished by non-overlapping morphological characters, including colour pattern, and by patterns in their independent evolutionary histories. The same can be said for morphologically-congruous popula- tions separated by deep molecular differences. Such ‘cryptic’ species are uncommon, but E. darabensis appears to be a genuine example. Esmaeili et al. (2014 b, 2020) suggested that it is most closely related to E. persicus , from which it is well distinguished by colour pattern, while it is morphologically identical to E. sophiae .

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.