Orchestomerus wickhami, DIETZ, 1896

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1649/0010-065X-68.1.158 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B187DC-FFD2-6622-69ED-26F3FEDAB0FC |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Orchestomerus wickhami |

| status |

|

ORCHESTOMERUS WICKHAMI DIETZ View in CoL ( COLEOPTERA : CURCULIONIDAE : CEUTORHYNCHINAE ) REARED FROM LEAF MINES IN VIRGINIA CREEPER ( PARTHENOCISSUS PLANCH. , VITACEAE )

CHARLES S. EISEMAN Northfield, MA 01360, U.S.A. ceiseman@gmail.com

The only North American insects recorded as mining in leaves of the grape family ( Vitaceae ) are moths in the genera Antispila Hübner (Heliozelidae) and Phyllocnistis Zeller (Gracillariidae) . In both taxa, more reared specimens are needed to determine how many species are involved and how they correspond with the different types of mines on grape ( Vitis L.) and Virginia creeper ( Parthenocissus Planch. ) (Nieukerken et al. 2012; D. R. Davis, in litt.).

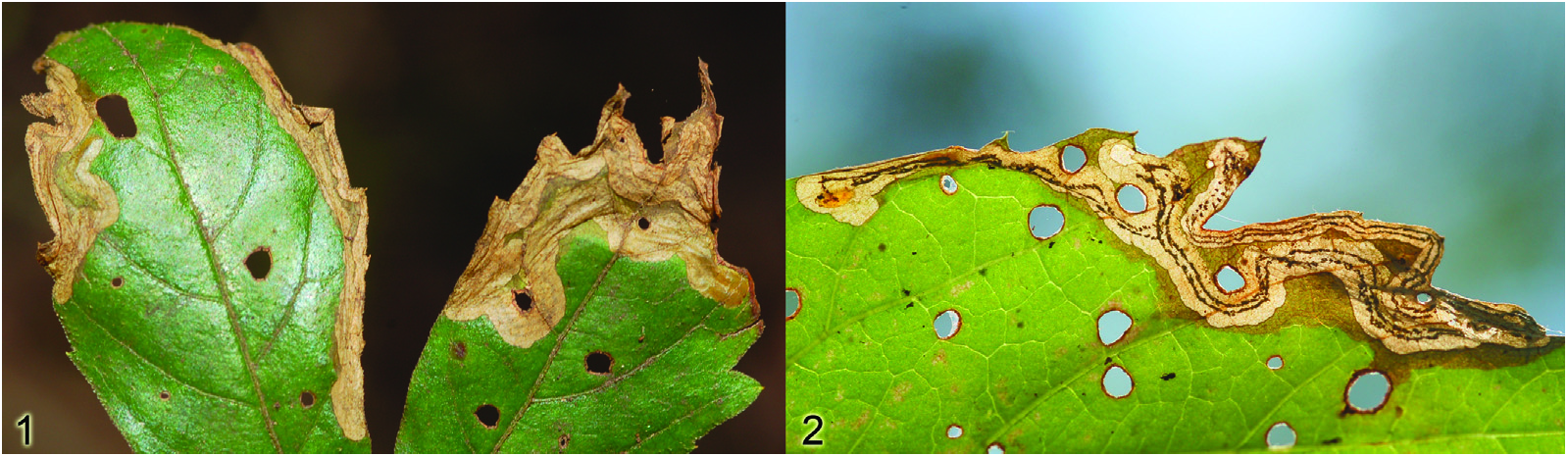

It was with this in mind that I paused to examine some low-growing Virginia creeper along a logging road just to the north of Lake Nippenicket in Bridgewater, Massachusetts on 16 August 2013. In addition to mines of both Antispila and Phyllocnistis , I found some that were clearly unrelated to either. The mines were full depth ( i.e., all of the mesophyll was consumed) and consequently plainly visible from either leaf surface, distinguishing them from Phyllocnistis mines which are visible on only one leaf surface. Antispila mines are likewise full-depth, but consist of a narrow linear portion followed by a blotch. These mines were essentially linear throughout their length, gradually increasing in width from about 1 to 3 mm, much longer and wider than the linear portions of Antispila mines ( Fig. 1 View Figs ).

In about 30 minutes of searching, I found just three leaflets bearing these mines, and each of these leaflets contained two larvae. These were bright yellow and legless, and among leaf-mining larvae known to me they most closely resembled agromyzid flies as viewed through the leaf epidermis by the naked eye. In two of the three leaflets, the two larvae fed side by side in a common mine — a highly unusual feature among leafminers producing linear mines, although it also occurs in the tropical beetle Pachyschelus psychotriae Fisher (Buprestidae) (Hespenheide and Kim 1992) and in the early stages of some muscoid fly mines. Each larva deposited its excrement in a narrow, more or less continuous, central line ( Fig. 2 View Figs ). In all cases, the mines followed the leaf edge for some distance and then doubled back on themselves.

I collected the leaflets in a plastic vial, and on 18 August the first larva emerged. Outside the mine, its distinct brown head was apparent, distinguishing it from any terrestrial leaf-mining fly larva. Its body shape — broadest near the posterior end and narrowing toward the head — was unlike that of any moth, beetle, or sawfly leafminer of which I knew ( Fig. 3 View Figs ). I transferred it and the three leaflets to a small jar with a moistened mixture of peat and sand about 3 cm deep. Ultimately,

Although the weevils were kept alive for several days and offered fresh Virginia creeper leaves, they were not observed to feed. All three mined leaflets had been riddled with holes at the time of collection, but although other ceutorhynchines leave similar feeding holes ( e.g., I have seen Dietzella zimmermanni (Gyllenhal) leave holes in enchanter ’ s nightshade ( Circaea lutetiana L., Onagraceae )), these could also have been made by flea beetles ( Altica Geoffroy , Chrysomelidae ).

R. S. Anderson examined the specimens and confirmed them as Orchestomerus wickhami Dietz , which has not previously been associated with any host plant. Of the 11 other described Orchestomerus species , two are known from the USA and have been collected as adults on grape. The remaining species occur from Mexico to Argentina and their ecology is unknown ( Colonnelli 2004). Larvae of Craponius inaequalis (Say) , also in the tribe Cnemogonini , feed within grape seeds (Blatchley and Leng 1916). No ceutorhynchine has previously been recorded from Virginia creeper ( Colonnelli 2004).

Because Dietz (1896) described each of the first two Orchestomerus species based on a single caught adult specimen, the resemblance of the name to the leaf-mining genus Orchestes Illiger ( Curculionidae : Curculioninae ) is evidently coincidental. This rearing of O. wickhami appears to be the first documentation of leaf-mining by a ceutorhynchine in North America. In Europe, Ceutorhynchus contractus (Marsham) and Ceutorhynchus insularis Dieckmann mine leaves of Brassicaceae and related families ( Hering 1951; Anonymous 2013). Additional leafminers may remain to be discovered among the many North American species of Ceutorhynchus Germar on mustards or the two Orchestomerus species on grape.

4) Pupa; 5) Adult.

four larvae emerged, one of them burrowing into the soil and three remaining on the surface. Two larvae were apparently dead in their common mine at the time of collection.

On 23 August, two of the larvae on the soil surface had pupated. The third died and began to grow mold. The pupae were yellow like the larvae and bore several long setae on the head, thorax, and legs ( Fig. 4 View Figs ). On 31 August, both visible pupae had eclosed, revealing the insects as weevils in the genus Orchestomerus Dietz (Curculionidae) . They were pale orange at first and were not fully colored until the next day. On 5 September, the weevil that had pupated in the soil appeared on the surface ( Fig. 5 View Figs ).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.