Coccothrinax argentata (Jacquin) Bailey (1939a: 223)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/phytotaxa.614.1.1 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8400386 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B387DA-FFE8-1F74-FF50-FD03FDAC8D23 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Coccothrinax argentata (Jacquin) Bailey (1939a: 223) |

| status |

|

1.2. Coccothrinax argentata (Jacquin) Bailey (1939a: 223) View in CoL View at ENA .

Palma argentata Jacquin (1803: 38) View in CoL .

Type:— Jacquin 1803, tab. 43, fig. 1. Epitype (designated here):— BAHAMAS. Great Exuma, near George Town airport, 9 July 1978, D. Correll 49994 (epitype NY!). Plate 2 View PLATE 2

Coccothrinax garberi (Chapman) Sargent (1899: 90) View in CoL . Thrinax garberi Chapman (1878: 12) View in CoL . Thrinax argentea var. garberi (Chapman) Chapman (1897: 462) View in CoL . Coccothrinax argentata subsp. garberi (Chapman) Zona, Francisco-Ortega & Jestrow View in CoL in Zona et al. (2018: 160).

Lectotype (designated here):— USA. Miami, June–August 1877, A. Garber s.n. (lectotype NY!, isolectotypes FLAS!, GH!, US!).

Coccothrinax jucunda Sargent (1899: 89) View in CoL . Lectotype (designated here):— USA. Florida, between Bay Biscayne and the Everglades, May , A. Curtiss 2679 (lectotype NY!).

Coccothrinax jucunda var. macrosperma Beccari (1907: 312) View in CoL . Type :— BAHAMAS. Fortune Island, 5 February 1888, H. Eggers 3872 (holotype B, destroyed).

Coccothrinax jucunda var. marquesensis Beccari (1907: 313) View in CoL . Lectotype (designated here):— USA. Florida, Marquesas Keys , November 1887, C. Sargent s.n. (lectotype A!).

Coccothrinax litoralis León (1939: 138) View in CoL . Lectotype (designated by Moya 2020):— CUBA. Oriente, Bahia de Manatí, Playa de Muertos, 29 December 1933, Fr. León 16017 (lectotype HAC!, isolectotype MT n.v., MT image!).

Coccothrinax victorinii León (1939: 139) View in CoL . Lectotype (designated by Moya 2020):— CUBA. Oriente, entre las 2 bocas del río Tana, Media Luna, 29 December 1938, Fr. León 18604 (lectotype HAC!, isolectotypes A!, BH!, MICH n.v., MICH image!, US!).

Coccothrinax inaguensis Read (1966a: 30) View in CoL . Type :— Cultivated plant from seed collected on Great Inagua , USDA Plant Introduction Station, Miami, Florida, 24 February 1965, R. Read 1377 (holotype BH!, isotypes FTG!, US!).

Coccothrinax jamaicensis Read (1966b: 133) View in CoL . Type:— JAMAICA. St.Ann , Queen’s Highway, sea level, 15 November 1965, R. Read 1563 (holotype BH!, isotypes FTG n.v., FTG image!, GH!, S n.v., S image!, UCWI n.v., US!) .

Coccothrinax readii Quero (1980: 118) View in CoL . Type:— MEXICO. Quintana Roo, ½ km al norte de Xel-ha, 10 m, 26 May 1979, H. Quero 2755 (holotype MEXU n.v., MEXU image!, isotypes BH!, F n.v., F image!, GH!, NY!, US!) .

Coccothrinax proctorii Read (1980: 285) View in CoL . Type:— CAYMAN ISLANDS. Grand Cayman, east of Savannah village , 9 June 1967, G. Proctor 27991 (holotype IJ n.v., isotypes FTG!, US n.v.) .

Stems 2.5(0.03–6.0) m long and 8.2(2.9–15.0) cm diameter, solitary. Leaves more or less deciduous or only leaf bases persisting on stem; leaf sheath fibers 0.3(0.1–0.5) mm diameter, closely woven, not forming persistent ligules and soon disintegrating at the apices; petioles 8.6(2.0–17.4) mm diameter just below the apex; palmans 11.8(1.3–30.5) cm long, relatively long, without prominent adaxial veins; leaf blades not wedge-shaped; segments 31(12–49) per leaf, the middle ones 49.5(17.2–90.0) cm long and 2.1(0.8–4.2) cm wide; segments pendulous at the apices, giving a three-dimensional appearance to the leaf; middle leaf segments relatively long and narrow, tapering from base to apex, scarcely folded, flexible and not leathery, a shoulder or constriction absent or poorly developed, the apices thin, deeply splitting and breaking off; middle leaf segment apices attenuate; leaf segments not waxy or sometimes with a deciduous, thin layer of wax adaxially, densely indumentose abaxially, with irregularly shaped, persistent, interlocking, fimbriate hairs, each one with a conspicuous, reddish-brown, pale brown, or greenish elliptic center, or without indumentum, scales, or wax abaxially, without transverse veinlets. Inflorescences curving, arching, or pendulous amongst the leaves, with few to numerous partial inflorescences; rachis bracts somewhat flattened, loosely sheathing, usually tomentose with a dense tuft of erect hairs at the apex; partial inflorescences 4(2–7); proximalmost rachillae straight, 7.1(2.5–15.0) cm long and 1.1(0.6–1.8) mm diameter in fruit; rachillae glabrous at or near anthesis; stamens 9(8–10); fruit pedicels 2.3(0.8–6.2) mm long; fruits 7.8(5.3–10.6) mm long and 7.5(5.1–10.0) mm diameter, black, purple, purple-black, red-black, reddish-black, red-purple, or burgundy; fruit surfaces smooth or sometimes with projecting fibers; seed surfaces deeply lobed, the lobes running from base of seeds almost to apices.

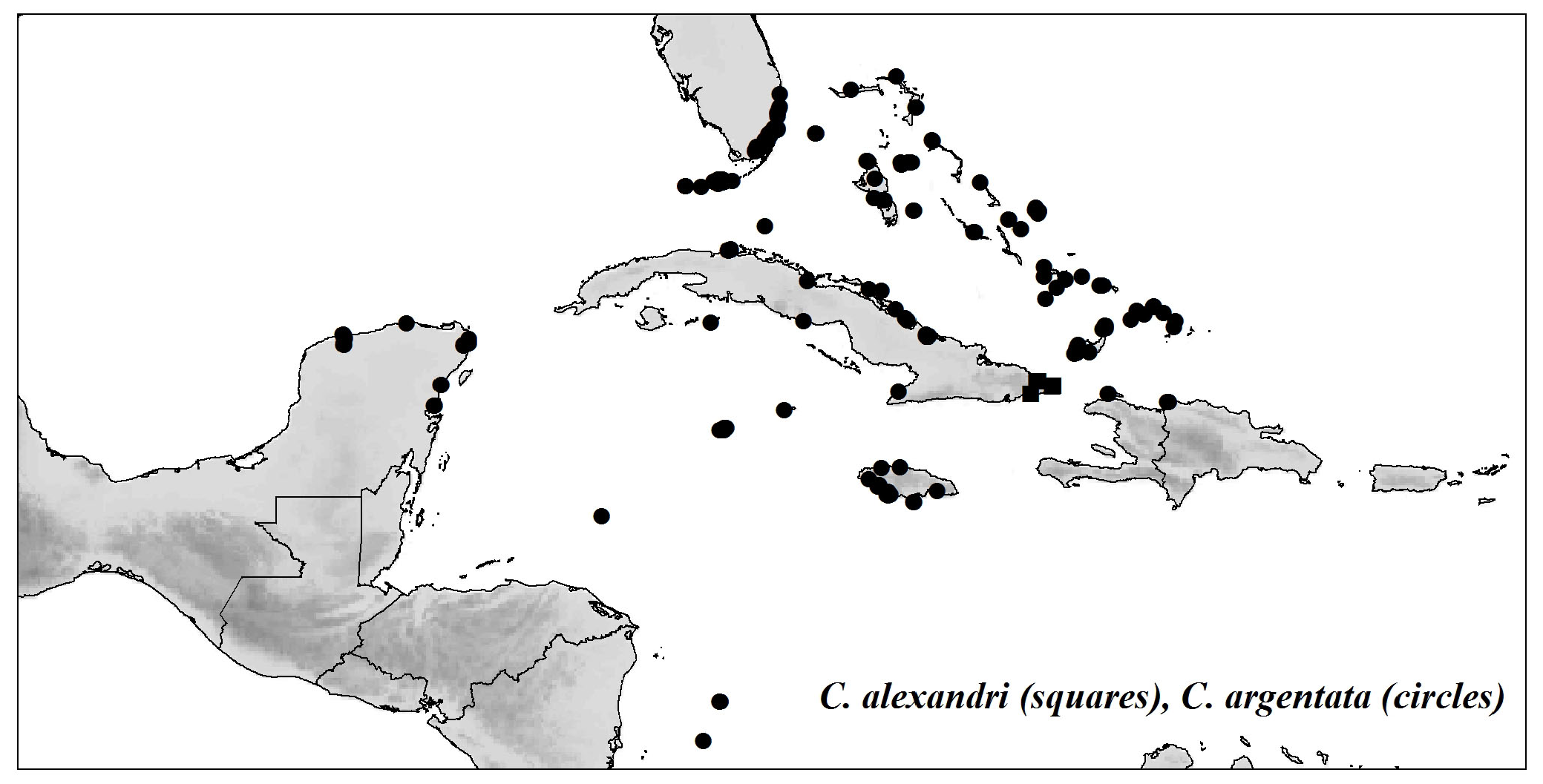

Distribution and habitat:— USA (Florida), Bahamas, Turks and Caicos Islands, Hispaniola, Cuba, Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Mexico (Quintana Roo, Yucatán), Colombia (San Andrés, Providencia) and Honduras (Islas del Cisne) ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ) in pine woods, shrubby areas, coastal coppices, thickets, on limestone soils or sand dunes usually near the sea, at 89(0–488) m elevation. Duno de Stefano & Moya (2014) reported that C. argentata also occurs in Belize but no specimens from there have been seen.

Taxonomic notes:— Seven preliminary species ( Coccothrinax argentata , C. inaguensis , C. jamaicensis , C. litoralis , C. proctorii , C. readii , C. victorinii ) share a unique combination of qualitative character states (with one exception, as discussed below) and are recognized as a single phylogenetic species, the earliest name for which is C. argentata . Jacquin (1803) described Palma argentata from a cultivated plant said to come from the Bahamas, and illustrated it with a figure of a single leaf. Because the illustration is equivocal, an epitype is designated. Coccothrinax argentata is widespread in the western Caribbean and occurs in several different areas.

Subspecific variation:—In the USA, in mainland Florida, plants occur in southern Palm Beach, Broward, and Miami-Dade counties, where they grow in coastal pinelands or open areas at low elevations ( Small 1924). Specimens have been identified as Coccothrinax argentata . Two other names have been applied to specimens from this area, C. garberi and C. jucunda , but these are included as synonyms of C. argentata ( POWO 2023) and their types share all character states with other specimens. Specimens are notable for their leaf segments that are densely indumentose abaxially, each hair with a conspicuous, reddish-brown, elliptic center. Davis et al. (2007) and Zona et al. (2018) reported that plants from Palm Beach and Broward counties, growing on sand dunes, had stems up to 2 m tall. On the other hand, plants from Miami-Dade county, growing in pine rock land over oolitic limestone, were smaller with stems usually less than 1 m tall. Differences in several variables were found, with plants from Palm Beach and Broward counties being larger than those from Miami-Dade county. In the present study, although there are not enough data to test for stem length, specimens from Palm Beach and Broward counties differ from those of Miami-Dade county in eight variables (petiole width, palman length, number of segments, segment length, segment width, number of partial inflorescences, fruit length, fruit diameter) (t -test, P <0.05), with specimens from Palm Beach and Broward counties having higher values for all variables.

In the Florida Keys, plants occur on Bahia Honda Key, Boot Key, Big Pine Key, No Name Key, Big Munson Island, and Marquesas Key and grow in open pinelands at low elevations, and have stems a mean of 1.7 m long. Specimens have been identified as Coccothrinax argentata . One other name has been applied to specimens from this area, C. jucunda var. marquesensis from Marquesas Key, but this is included as a synonym of C. argentata ( POWO 2023) and the type shares all character states with other specimens. Specimens have the same distinctive abaxial segment indumentum as those from mainland Florida. Quantitatively, specimens from the Florida Keys differ from those of the Florida mainland in eight variables (stem diameter, petiole width, palman length, number of segments, segment length, segment width, rachilla length, pedicel length) (t -test, P <0.05), with specimens from the Florida Keys having higher values for all variables. Davis et al. (2007) considered that the mainland and Keys plants were both part of a single, polymorphic species. On the other hand, Zona et al. (2018) considered that the two should be recognized as two separate subspecies (subspp. argentata and garberi ), based on both morphological and molecular data.

Nauman (1989, 1990) reported intergeneric hybrids between Coccothrinax argentata and Leucothrinax morrisii (as Thrinax morrisii ) on No Name Key and Big Pine Key.

In the Bahamas (excluding San Salvador, Rum Cay, Great Inagua, and Little Inagua) plants are widely distributed and occur in scrubby vegetation on sandy soils near the sea. Specimens have been identified as Coccothrinax argentata and the type is from the Bahamas. One other name has been applied to specimens from this area, C. jucunda var. macrosperma , but this is included as a synonym of C. argentata ( POWO 2023) and, judging from the protologue, it shares all character states with other specimens. Leaves of specimens from the Bahamas are indumentose abaxially, but the hairs lack the distinctive reddish-brown center of the Florida ones, except for a few specimens (e.g. Bailey 1025, 1048, Goldman 2468, Jestrow 62, Langlois s.n.) from Andros and Nassau. These specimens have hairs with exactly the same reddish-brown centers as the Florida ones. Leaf segment number of these Andros and Nassau specimens is also more similar to that of Florida Keys ones, rather than to other Bahamas ones, possibly indicating dispersal from the Florida Keys to Andros and Nassau. Some other specimens have leaves that are scarcely indumentose abaxially, although this may be a function of age of the leaves, because older leaves may loose their indumentum. Zona et al. (2018) considered that the Bahamas plants were similar to the Florida Keys ones. Quantitatively, specimens from the Bahamas differ from those of the Florida Keys in eight variables (petiole width, palman length, number of segments, segment length, segment width, rachilla width, pedicel length, fruit length) (t -test, P <0.05), with specimens from the Bahamas having higher values for all variables.

Read (1966a) described specimens from San Salvador and Great Inagua as Coccothrinax inaguensis , and later included specimens from Providenciales (the Turks and Caicos Islands) and Rum Cay. Here, all specimens from San Salvador, Rum Cay, Great Inagua, Little Inagua, and the Turks and Caicos Islands were determined as preliminary species C. inaguanensis . Plants occur in similar habitats to those of the Bahamas. Read (1966a) distinguished C. inaguanensis from C. argentata by its leaf segments abaxially without indumentum. However, indumentum is difficult to score as present or absent. Specimens from Great Inagua seem to be without indumentum, but those from Little Inagua and the Turks and Caicos Islands have a thin layer of indumentum, and one (Gillis 13139) has dense indumentum. Specimens from San Salvador have either a normal layer of indumentum or a thin layer or absent layer (e.g. Brooks 414). Nauman & Sanders (1991a) noted that on San Salvador intermediate states of indumentum occurred. Presence or absence of indumentum is here treated as a trait. Quantitatively, Read (1966a) distinguished C. inaguensis from C. argentata (from Florida and Bahamas) by its thinner stems, more segments, longer pedicels, and larger fruits. Here, C. inaguensis differs significantly from C. argentata from Florida and Bahamas in 10 variables (petiole width, palman length, number of segments, middle segment width, number of partial inflorescences, rachilla length, rachilla width, pedicel length, fruit length, fruit diameter), with C. inaguensis having higher values for all variables, but differs from C. argentata from Bahamas in only three variables (petiole width, middle segment length, fruit diameter) (t -test, P <0.05), with C. inaguensis having lower values for leaf variables and higher for the fruit variable. However, even within the area of C. inaguensis specimens are not uniform. As noted above, specimens from the Turks and Caicos Islands (Providenciales, South Caicos, North Caicos; excluding the single specimen from West Caicos) have a thin layer of indumentum on the leaves abaxially. They also have significantly thinner fibers and shorter pedicels (t -test, P <0.05) than other specimens determined as C. inaguensis . In summary, within the area of preliminary species C. inaguensis variation is quite complex and there may be at least three distinct populations: San Salvador; Great and Little Inagua (including West Caicos); and the Turks and Caicos Islands. There are too few specimens from other areas (Rum Cay) to test for differences. Nauman & Sanders (1991b) stated that C. inaguensis had “lorica remnants generally present” but it is not clear to what they were referring.

Two isolated populations occur on the north coast of Hispaniola. Several specimens from the Morro de Monte Cristi on the northwest coast of the Dominican Republic are somewhat tentatively included here. A similar specimen (Ekman 4144) from Tortuga island (just off the north coast of Haiti) is also tentatively included here. The US duplicate of this specimen was determined as C. inaguensis by Read, and in their long pedicels the specimens do resemble preliminary species C. inaguensis . However, the segments are indumentose abaxially and this appears more like that of C. argentea , although the indumentum appears to have worn off in many places. The north coast of Hispaniola is just over 100 km from the Inagua Islands.

In Cuba, plants occur all along the north coast from Matanzas to Las Tunas, and along the south coast in Sancti Spíritus and Granma, in sandy soils at low elevations near the sea. Craft (2017) indicated that plants occurred on the south coast from Matanzas to Sancti Spíritus and in extreme western Cuba in Pinar del Río, but no specimens from these areas have been seen in the present study. Craft (2017) also noted that plants from the south coast appeared more robust than the ones on the north coast. Cuban specimens have been identified as C. litoralis or C. victorinii . León (1939) compared C. litoralis to Florida and Bahamas plants but considered they differed in their leaf segments, inflorescences, and seeds. Nauman & Sanders (1991a) and Craft (2017) considered these Cuban plants to be close to Florida and Bahamas ones. Most specimens have leaf hairs with the same distinctive reddish-brown, elliptic center as found in those from Florida, but in two specimens (Ekman 18555, Shafer 2603) the centers are lighter colored and difficult to distinguish. Quantitatively, specimens of C. litoralis differ from those of Florida and Bahamas in six variables (fiber width, palman length, segment length, segment width, number of partial inflorescences, rachilla length) (t -test, P <0.05), with specimens of C. litoralis having higher values for all variables. The specimen from eastern Cuba in Granma was described as C. victorinii , but this is included here as a synonym of C. argentata because the type shares all character states with other specimens. It does, however, have an unusually long ligule.

In Jamaica plants occur in coastal areas but in various habitats such as on sand dunes or dog’s tooth limestone, at 236(0–488) m elevation. Jamaican specimens have been identified as C. jamaicensis . Read (1966b) compared this with the Cuban C. fragrans , from which it was said to differ in its longer palmans, conspicuous silvery versus inconspicuous whitish abaxial leaf segment surfaces, more partial inflorescences, whitish versus yellowish flowers, and shorter hastulas. Read considered plants to be highly variable and gave a detailed discussion of variation in the island. As a preliminary species, C. jamaicensis is notable for the wide range in elevation.

Along the coast of Mexico, in Quintana Roo and Yucatán, plants occur in low forest on karst limestone at 7(4–10) m elevation. This population also extends into northern Belize ( Duno de Stefano & Moya 2014) but no specimens from there have been seen in the present study. Specimens from Mexico and Belize have been identified as C. readii . Quero (1980) distinguished C. readii from C. argentata by its bifid hastulas, and gave a detailed discussion of variation. However, Quero apparently did not see specimens (e.g. Kiem 403, Moore 8088) from Puerto Juárez in Quintana Roo that have apiculate hastulas like those of other specimens of C. argentata . Nor did Quero (1980) take into account specimens from the Cayman Islands with bifid hastulas (see below). As pointed out by Nauman & Sanders (1991a), hastula shape is too variable to be useful taxonomically. Most specimens from Mexico have the same distinctive reddish-brown elliptic center to the scales on the abaxial leaf surface as those from Florida, but in others this center is greenish and difficult to distinguish.

In the Cayman Islands, on both Grand Cayman and Little Cayman, plants occur on sandy soils at low elevations near the sea. Specimens have been identified as C. proctorii . Read (1980), in describing C. proctorii , compared it with C. jamaicensis and distinguished it by its longer fruiting pedicels and leaf anatomical characters. Fruiting pedicels are known from only two specimens of C. proctorii , and these are 3.6–4.6 mm long versus 2.5–4.0 mm long in C. jamaicensis . Nauman & Sanders (1991a) noted that some specimens had “two toothed hastulas” (like the Mexican populations). They considered C. proctorii to be intermediate between C. jamaicensis and Mexican populations “in usually having one or more leaves per plant with two-toothed hastulas”. Leaf segments abaxially are similar to those of the Bahamas population.

Specimens are known from the Colombian islands of San Andrés and Providencia, where they have been identified as C. argentata ( Galeano-Garcés 1986) , and from the Honduran Islas del Cisne, where they have been identified as C. jamaicensis .

According to the methods used in this study, subspecies may be recognized if subgroups within a species can be delimited by geographic/elevation disjunctions, and these subgroups differ in quantitative variables. In the case of the C. argentata , there are numerous potential subspecies based on geographic disjunction, as discussed above. In fact, subspecies based on one such disjunction have already been proposed (subspp. garberi and argentata, Zona et al. 2018 ). However, subspecies are not recognized here for the following reasons. First, there are too few specimens from most islands to test for differences in quantitative variables. Second, there are approximately 40 different, disjunct populations of C. argentata , most of them on islands, each a potential subspecies. Recognizing these would give an unwieldly number of subspecies. Third, as outlined at the beginning of the Results section, there are problems based on dispersal and hybridization. For example, some Bahamas specimens are exactly like the mainland Florida ones, and some Cayman specimens have hastulas like the Mexican ones. In summary, C. argentata occurs in approximately 40, disjunct, island and mainland populations, several of which differ quantitatively but with evidence of dispersal and hybridization amongst these populations.

| R |

Departamento de Geologia, Universidad de Chile |

| BH |

L. H. Bailey Hortorium, Cornell University |

| FTG |

Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden |

| GH |

Harvard University - Gray Herbarium |

| S |

Department of Botany, Swedish Museum of Natural History |

| UCWI |

University of the West Indies |

| H |

University of Helsinki |

| MEXU |

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México |

| F |

Field Museum of Natural History, Botany Department |

| NY |

William and Lynda Steere Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden |

| G |

Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de la Ville de Genève |

| IJ |

Natural History Museum of Jamaica (NHMJ) |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Coccothrinax argentata (Jacquin) Bailey (1939a: 223)

| Henderson, Andrew 2023 |

Coccothrinax readii

| Quero, H. 1980: ) |

Coccothrinax proctorii

| Read, R. 1980: ) |

Coccothrinax inaguensis

| Read, R. 1966: ) |

Coccothrinax jamaicensis

| Read, R. 1966: ) |

Coccothrinax jucunda var. macrosperma

| Beccari, O. 1907: ) |

Coccothrinax jucunda var. marquesensis

| Beccari, O. 1907: ) |

Coccothrinax garberi (Chapman)

| Zona, S. & Hass, M. & Fickerova, M. & Mardonovich, S. & Sanderford, K & Francisco-Ortega, J. & Jestrow, B. 2018: 160 |

| Sargent, C. 1899: ) |

| Chapman, A. 1897: ) |

| Chapman, A. 1878: ) |

Coccothrinax jucunda

| Sargent, C. 1899: ) |