Goniopholis kiplingi, Andrade & Edmonds & Benton & Schouten, 2011

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00709.x |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B40213-FFCB-FF9C-FEF8-53E5FC4AF891 |

|

treatment provided by |

Valdenar |

|

scientific name |

Goniopholis kiplingi |

| status |

sp. nov. |

GONIOPHOLIS KIPLINGI SP. NOV.

Etymology: Specific name after Rudyard Kipling, British novelist, author of ‘The Jungle Book’ amongst others and an important disseminator of natural sciences through literature, from the end of the 19 th century to the beginning of the 20 th century.

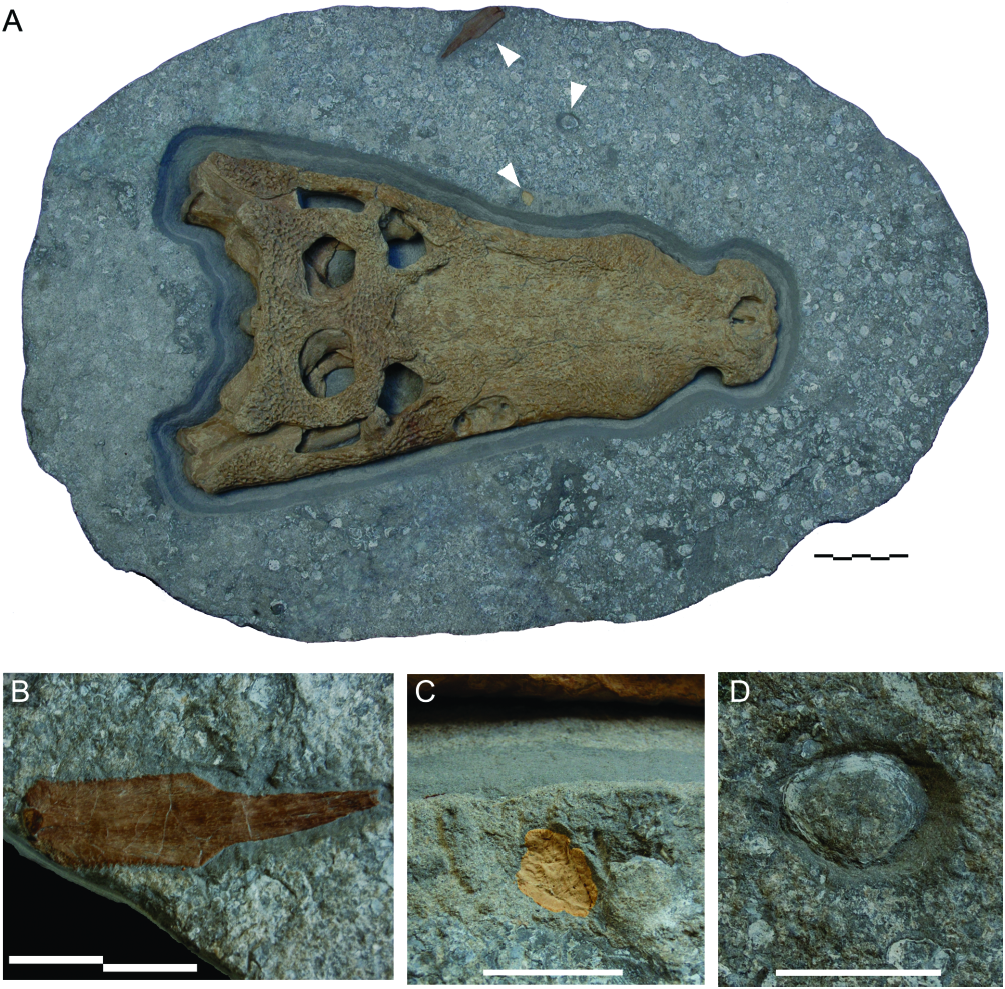

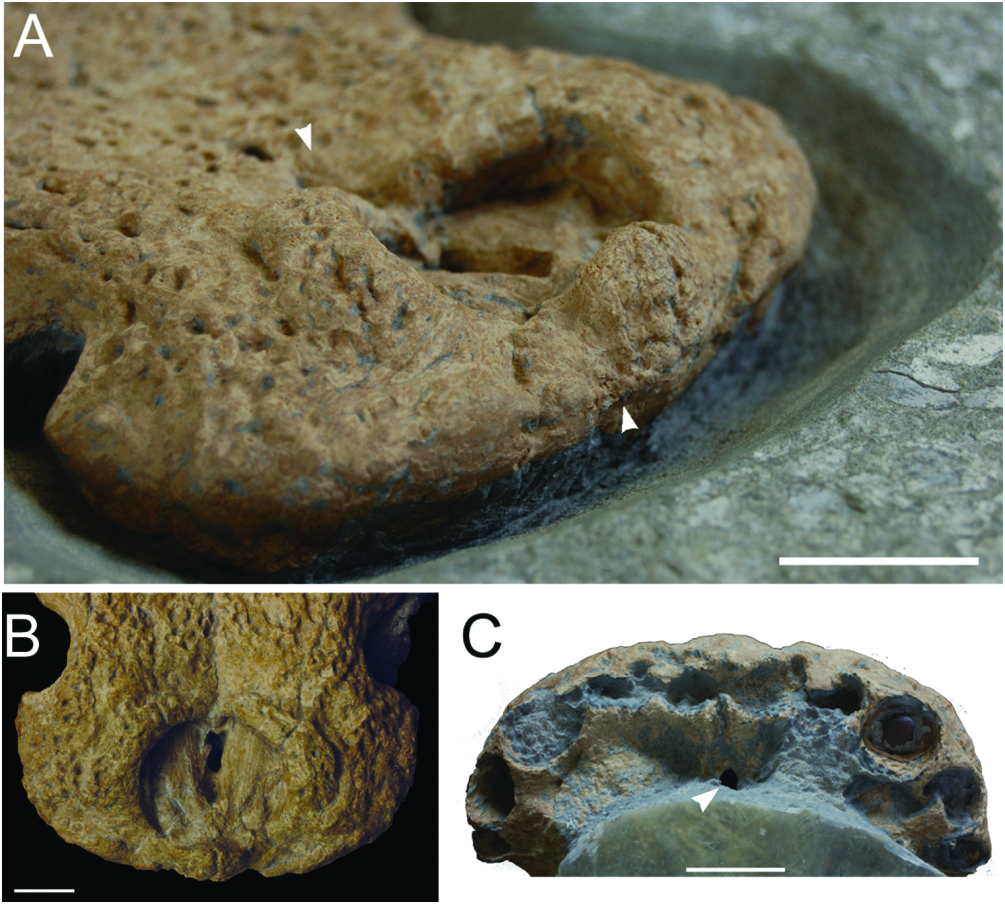

Holotype: DORCM 12154 View Materials , well-preserved skull, dorsoventrally flattened, lacking mandibles and most teeth ( Figs 1 View Figure 1 , 6–11 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 View Figure 9 View Figure 10 View Figure 11 ).

Type-locality: Cliff at GR SZ 038785, north end of Durlston Bay , Swanage, Jurassic Coast, Dorset, England, UK; GPS coordinates: 50°36′22.49478″N , - 01°56′49.47318″W GoogleMaps .

Type-stratum: Bed 129b ( Clements, 1993), Intermarine beds sensu Wimbledon in Benton & Spencer (1995; = Intermarine Member sensu Clements, 1993), Stair Hole Member sensu Westhead & Mather (1996), Purbeck Limestone Group; Berriasian, Lower Cretaceous ( Salisbury et al., 1999; Milner & Batten, 2002). Sediment directly associated with the specimen preserved and catalogued under the same number as the type.

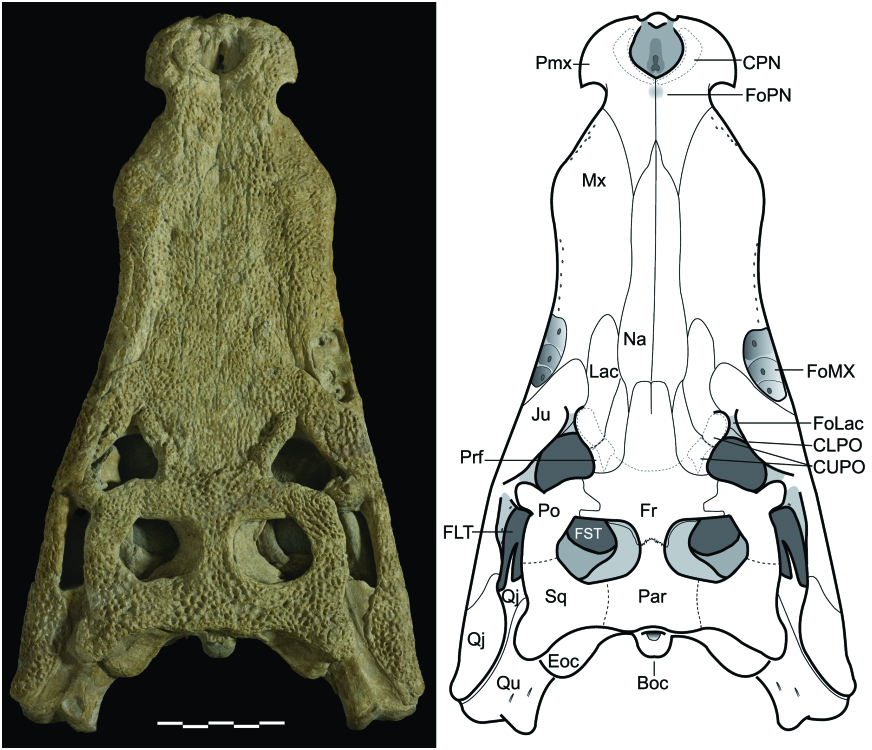

Diagnosis for the species (autapomorphies indicated by ‘*’): Goniopholidid mesoeucrocodylian with the unique combination of the following features: skull sublongirostrine, with rostrum between 66–70% of skull length (*); premaxillae in the shape of an axe head, in dorsal view, with deep notches at premaxilla- maxilla suture; naris orientated fully dorsally; perinarial crests present; narial border high throughout, but anterolateral border with deep notch on both sides; nasals widely excluded from narial border by posterordorsal branches of premaxillae; naso-oral foramen present and fully open, formed by premaxillae and maxillae; naso-oral fossa diamondshaped; maxillary depressions with all borders well defined, and three internal chambers, the first being the largest, and chambers decreasing in size posteriorly and bearing a neurovascular foramen at the bottom; lachrymals proportionally long and narrow, extending anteriorly beyond the maxillary depressions, but not tapering anteriorly (*); upper periorbital crest strong and divided into a longer anterior (lachrymal) and shorter posterior (prefrontal) sections; lachrymal fossa with extensive participation of jugal, but not of prefrontal; prefrontal extending posteriorly to the posteromedial border of the orbit; frontal participating at posteromedial (primary) border of the orbit; frontoparietal suture well within the intertemporal bar; supratemporal fossae subpolygonal, at least as large as orbit; frontal- postorbital suture complex; postorbital with anterolaterally directed process, short and robust; quadrate with two foramina aerum, one at posteromedial corner, one at dorsal surface; dorsal and posteromedial surfaces of quadrate separated by a smooth ridge (not acute crest); teeth crowns keeled, with enamel ornamented by thin, well-defined basi-apical ridges, non-anastomosed (base of the crown) to poorly anastomosed (appex), creating crenulations (falseserrations) on the keels.

DESCRIPTION OF GONIOPHOLIS KIPLINGI DORCM 12154

General features of the skull

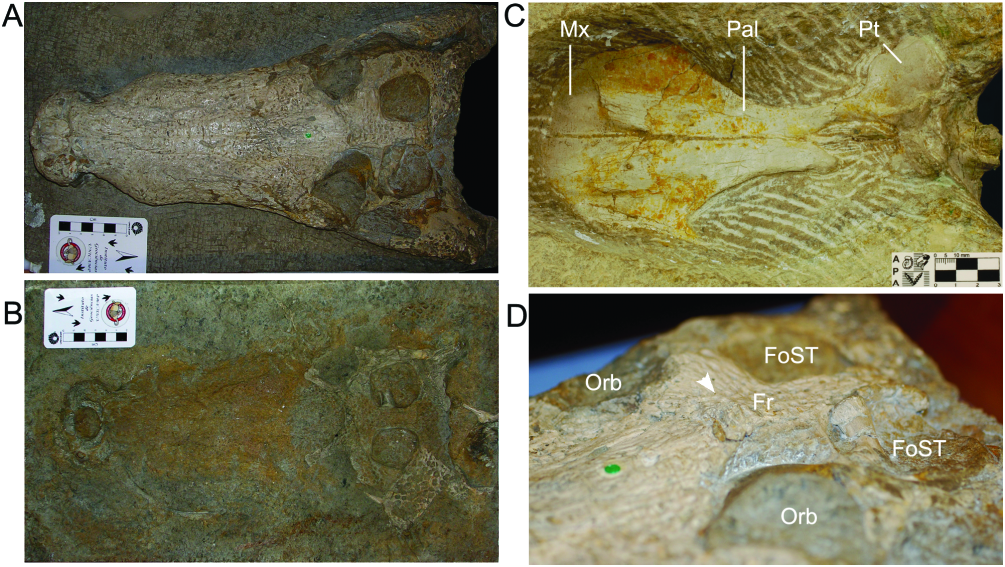

The skull ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ) is sublongirostrine (rostrum 68.5% of skull length; RL/SWPo = 1.76) and its relative length is slightly longer than in G. simus and G. baryglyphaeus . Perinarial, periorbital, and transfrontal crests are present. As in most other neosuchians, there is no antorbital fenestra or fossa. Orbits are orientated laterally and dorsally, with only a small anterior component, as in G. simus . The length of the DORCM 12154 skull ( 475.6mm; premaxilla to occipital surface) gives a total body length estimate of 3.47 metres based on ‘body length/head length’ regressions provided by Sereno et al. (2001).

The laterotemporal fenestra is triangular and faces laterodorsally, as in most Mesoeucrocodylia . The supratemporal fenestra is ample, but still slightly smaller than the orbit. A supratemporal fossa surrounds the fenestra itself, and has the approximate size of the orbit. The subpolygonal outline of the supratemporal fossa is more evident on the left side, whereas the border of the fenestra on the right side looks rounder because of preservation/preparation. A post-temporal fenestra is present and evident, wider than high and close to the medial line of the skull. The squamoso-otoccipital fenestra was obliterated by the dorsoventral deformation of the specimen.

The rostrum was relatively narrow and moderately high, prior to deformation. It broadens posteriorly, smoothly fitting the skull at orbits, with rostrum limits poorly defined, as in most other related genera (e.g. Sunosuchus , Eutretauranosuchus , Siamosuchus ), and in contrast to the morphology in Pholidosaurus . The dorsal surfaces of frontal, parietal, postorbital, and squamosal composing the skull roof are flat, forming the skull roof.

Postnarial fossa: DORCM 12154 has a small, poorly defined fossa immediately posterior to the narial opening ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ; character 41). The internal surface of this depression is also ornamented. The depression itself is mostly shallow and with poorly defined limits. Sampling this potentially informative character is difficult because it is frequently overlooked and assumed to be taphonomic. It requires direct observation, explicit mention in the text, or imaging techniques that provide three-dimensional information (stereophotography, tomography data). Direct examination of specimens showed that at least G. simus , G. baryglyphaeus , and the undescribed ‘Hulke’s goniopholidid’ share the same feature, and it is absent in Sarcosuchus , Elosuchus , and dyrosaurids. Calsoyasuchus completely lacks such a depression ( Tykoski et al., 2002), as shown by tomography data. Images of Amphicotylus (D. Pol, pers. comm. 2010) suggest the presence of the fossa in this taxon, and indeed the structure may be present in several other goniopholidids, but it is not properly noted for taxa such as Denazinosuchus and Eutretaurnosuchus.

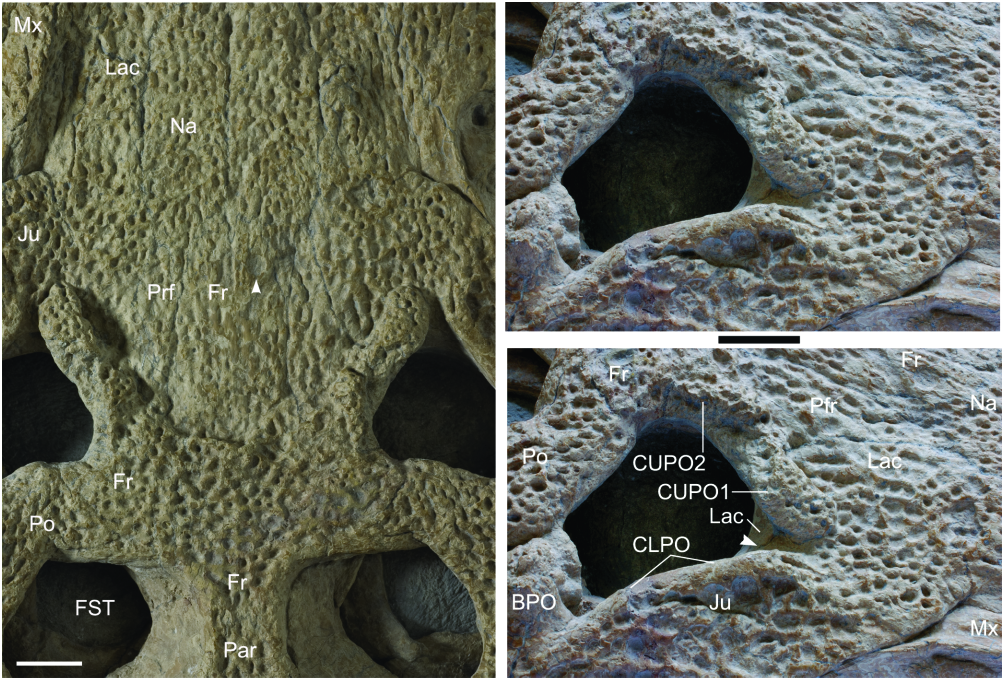

Lachrymal fossa: Although the antorbital fossa is absent in DORCM 12154, a small fossa is present immediately anterior to the orbit, in the lachrymal area ( Fig. 8 View Figure 8 ; character 53). In this fossa, the bone surface is unornamented and extremely concave. The limits of this fossa are made evident by the anterior end of the periorbital crests. Within Goniopholididae , the fossa is present in most taxa ( Goniopholis , Amphicotylus , Nannosuchus ), but it is unknown in Sunosuchus and Siamosuchus , and absent in Calsoyasuchus . The undescribed goniopholidids (BMNHB 001876, BMNH R3876, IRSNB R47) included in the study also have a small, well-defined fossa. Most other groups of crocodylomorphs (e.g. sphenosuchians, protosuchians, notosuchians, metriorhynchids, atoposaurids) have an even larger and deeper fossa, whereas Bernissartia and eusuchians seem to lack this structure completely.

The naming of this fossa is confusing because of its position, and also its variable composition within Mesoeucrocodylia . This fossa may be erroneously identified as the antorbital fossa, as in many cases these structures occupy the same general area, anterior to the eye (e.g. Sphagesaurus , Notosuchus ; see Pol, 2003; Andrade & Bertini, 2008a, b, c). Nonetheless, they cannot be considered homologous structures because both are present as separate elements in several taxa (e.g. metriorhynchids, Hsisosuchus , Mahajangasuchus ). The use of names such as preorbital fossa or postantorbital fossa would only add more confusion, and so Young & Andrade (2009) defined this as the prefrontal- lachrymal fossa whilst revising Geosaurus giganteus , as in this taxon the prefrontal constituted almost half of the concavity. However, in the case of Goniopholis and other goniopholidids, the prefrontal does not participate in the anterior border of the orbit (character 160). As in other European Goniopholis and related forms (Hulke’s, Dollo’s, and Hooley’s goniopholidids), the jugal of DORCM 12154 broadly participates in the ventral part of the fossa, contributing to the anterior border of the orbit. In Amphicotylus , Sunosuchus , and Calsoyasuchus , neither prefrontal nor jugal seem to advance on the lachrymal region. Despite these problems, the fossa is always located immediately anterior to the orbit and the lachrymal bone always participates in the fossa. Therefore, the topological position of the fossa is taken as a reference, not its composition, and this structure is here designated as the lachrymal fossa, simply meaning that this is a fossa located in the lachrymal region, immediately anterior to the orbit.

Ornamentation and crests: Considering the dorsal elements of the skull, ornamentation does not occur inside the narial opening, alveolar margin of maxillae and maxillary depressions, temporal fossae, quadrate, medial section of the quadratojugal, and postorbital bar. All other surfaces are heavily ornamented with a modified version of the same pattern usually found in eusuchians, characterized by pits and grooves. In this specimen, however, no grooves ( sensu Buffrénil, 1982) are present, and pits are no more than ellipsoid ( Figs 6–8 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 ). Despite most of the ornamentation constituting an irregularly distributed fabric of pits, there are long rows of subcircular pits on the lateral surface of the jugal. Overall, the ornamentation is greatly similar to that found in most goniopholidids, Elosuchus , and Vectisuchus .

Unlike the morphology found in eusuchians and sebecians, the bony surface next to the alveolar margin is mostly smooth, lacking ornamentation, both in the premaxilla and maxilla ( Figs 7 View Figure 7 , 9 View Figure 9 ). In DORCM 12154, the ornamentation only approaches the ventral rim of the lateral maxillary surface at the fourth and fifth maxillary alveoli. Therefore, the alveolar margin resembles the condition found in several notosuchians and basal crocodyliforms. The smooth surface completely surrounds the maxillary depressions. The skull ornamentation does not progress ventral to the ventral-most neurovascular foramina of the premaxilla and maxilla, and the same occurs in the mandible (Ballerstedt casts BMNH R5260/R5261). This is common to all Goniopholis specimens examined, as well as to the undescribed goniopholidids and Nannosuchus (even though it lacks the maxillary depressions). This pattern of ornamentation has never been recognized in the group, although it must be noted that several of the specimens are partially embedded in matrix and mostly exposed dorsally, which presumably hampered observations.

Perinarial and periorbital crests are common in goniopholidids ( Figs 7 View Figure 7 , 8 View Figure 8 ). Upper orbital crests are also found in other neosuchians, and are particularly well developed in certain alligatorids (e.g. Melanouchus, Caiman; see Brochu, 1999). In Goniopholis , perinarial and periorbital crests are always robust and evident, and in many cases an interorbital crest links both upper periorbital crests at their posterior ends, dividing the frontal anterior process from its main body. However, the presence of a sagittal interorbital crest is not as frequent amongst goniopholidids, and is only reported for Siamosuchus (see Lauprasert et al., 2007) and Sunosuchus (e.g. Wu, Brinkman & Russel, 1996; Fu, Ming & Peng, 2005; Schellhorn et al., 2009).

The perinarial crests of DORCM 12154 ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ; character 29) begin medial to the distal end of the narial opening and progress anteriorly, encircling the naris for at least three-quarters of the narial perimeter, being absent from the anterolateral and anterior borders of the naris. At their posteromedial end, they are small and narrower, gradually increasing in size and width to the lateral margin of the naris, and then smoothly decreasing again towards their anterior ends. These crests are in contact posterior to the naris, but not truly continuous because of the presence of the medial suture between both premaxillae. The area immediately posterior to the medial contact of the perinarial crests is smoothly concave, forming a postnarial fossa. Perinarial crests seem to be absent from North American taxa and Sunosuchus , but occur in Amphicotylus (D. Pol, pers. comm. 2010). However, perinarial crests are present in Hulke’s goniopholidid, although no contact occurs between both, posterior to the narial opening.

The lower orbital crest ( Fig. 8 View Figure 8 ) is simply the dorsally projecting margin of the anterior jugal ramus, which runs lateral and ventral to the orbit, reaching the area immediately anterior to the orbit (lachrymal area). At this point, the dorsal edge of the jugal curves laterally, breaking from the jugal edge, and becomes a truly projecting blade that transects part of the dermal surface of the jugal. As the blade projects, the edge becomes evident as a crest, creates a notch at the anterior border of the orbit, and delimits the ventral end of the lachrymal fossa. This morphology is not exclusive to DORCM 12154, and can also be found at least in Amphicotylus (D. Pol, pers. comm. 2010), G. simus , and the goniopholidids reported by Hulke, Dollo, and Hooley.

The upper periorbital crests ( Fig. 8 View Figure 8 ) are preserved on both sides of DORCM 12154, set immediately medial to the dorsal border of the orbit. They provide extensive support to the palpebrals. In DORCM 12154 the dorsal periorbital crests are partially divided by a deep notch, where the lachrymal- prefrontal crosses the bony surface towards the orbit. The lachrymal section of the crest is elongated, whereas the prefrontal section is knoblike. Similar crests with a shallower notch also occur in most specimens of G. simus and G. baryglyphaeus , but the crest of Nannosuchus has no notch and is not as robust. As the robustness and the notch are more extreme in larger specimens, the differences between the crests seen in these specimens may reflect the ontogenetic stage. Upper periorbital crests provide extensive support to a single palpebral element. These crests are absent in Hulke’s, Dollo’s and Hooley’s specimens and also in Sunosuchus and Eutretauranosuchus , but are present in Goniopholis stovalli and possibly Amphicotylus .

DORCM 12154 shows a transversally orientated crest, transecting the frontal medial to the orbits and connecting with the posteromedial ends of the upper orbital crests ( Fig. 8 View Figure 8 ). Although continuous, the limits between these crests remain fairly recognizable. Whenever it occurs, the transfrontal interorbital crest is poorly arched, with the concavity facing anteriorly. At least G. baryglyphaeus , Nannosuchus , G. stovalli and possibly Amphicotylus also share this crest. As observed by Hooley (1907), both BMNH R3876 and Hulke’s specimen lack the crest completely. In DORCM 12154, as well as in G. simus , this crest isolates the main body of the frontal from its anterior process, and also delimits a difference in the depth of the dorsal surfaces of both, a condition absent in Nannosuchus and unknown in other taxa that have the transfrontal crest.

A similar transverse crest is present only in caimans ( Caiman latirostris, Melanosuchus), but is not as robust and is positioned on the rostrum, medial to the cranial border of the orbits, or anterior to it (see Brochu, 1999). The interorbital crest present in Goniopholis and other goniopholidids are here interpreted as different structures from those in alligatorids, although presumably analogous in their biomechanical function, and possibly contributing to the general robustness of the skull.

At the medial section of the crest, DORCM 12154 has a buttressed area, dorsally projected, flatter anteriorly and roughly triangular, in dorsal view (character 139). The same structure is present at least in G. simus ( type BMNH 41098 and the Ballerstedt casts BMNH R5259 and R5262; see Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ), but unreported in most other taxa. The undescribed Hulke’s goniopholidid bears a low, buttressed ‘hump’ at the same position, but this is poorly defined, with a circular profile (dorsal view). Furthermore, it is low, feebly projecting dorsally. Goniopholis baryglyphaeus has a buttressed area, but it expands transversally with the transfrontal crest and neither assumes the triangular profile nor truly projects dorsally. No other crocodylian apart from these British goniopholidids seems to have such a swollen area or projection medial to the orbits.

Rostrum

Nares: The narial opening ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ) is dorsally orientated, as its posterior border is dorsal to most of its anterior border, and is exclusively surrounded by the premaxillae. As in most Goniopholis , there is a perinarial crest at the rim of the naris (see ‘Ornamentation and crests’, above). The narial opening is proportionally wide (~30% of premaxillae width), as in G. simus , G. baryglyphaeus , and Amphicotylus lucasii , but unlike Hulke’s specimen. The narial opening is also slightly wider than long (AP/ ML = 0.89), as in G. simus . It has the same heartshaped profile that Salisbury et al. (1999) attributed to G. simus , but the posterior projection of the anterior border is not as pronounced as a result of preservation. The naris of both DORCM 12154 and G. simus differ substantially from the naris of Hulke’s specimen, which has a nearly perfect circular profile (AP/ML = 1.02).

Premaxillae: Premaxillae ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ) contact only the maxillae and nasals. Next to the premaxilla and maxillary suture there is a pronounced notch (for occlusion of a putative enlarged fourth dentary tooth) at the lateral alveolar margin. The lateral-most border of the premaxilla is directed posterolaterally, partially bounding the notch. This gives the premaxillae the appearance of a wide axe blade in dorsal view. The morphology is very similar to that in G. simus , G. baryglyphaeus , Hulke’s specimen, G. stovalli , Amphicotylus lucasii , and even the pholidosaurid Meridiosaurus , but unlike Nannosuchus , Siamosuchus (unknown in Hooley’s specimen and Denazinosuchus ), which are paddle-like in dorsal view.

Posterior to the naris, the premaxillae meet medially broadly, excluding the nasals from the narial border. The anterior rami of the premaxillae also form a high vertical wall at their medial contact. Immediately lateral to this contact there is a pronounced notch (character 34), at the anterolateral border of the narial opening. The overall morphology is very similar to that in G. simus , but no other specimen is known to have such a deep narial notch. The condition is unknown or undescribed in Eutretauranosuchus , Sunosuchus , Denazinosuchus , and Dollo’s and Hooley’s specimens (where the premaxilla is not preserved). Shallow unornamented areas are present in the same position in Hulke’s specimen, and are considered homologous. Paired anterior narial notches are probably present also in Amphicotylus (D. Pol, pers. comm. 2010).

The posterior ends of the premaxillae extend between and dorsal to the maxillae, and contact the nasals, creating a bifurcated profile. These posterior extensions are relatively long (~50% of anteroposterior length posterior to premaxilla- maxilla notch; ~60% of anteroposterior length posterior to naris). From the narial opening, the naso-oral fossa is visible. The naso-oral fenestra (= incisive foramen) is single, longer than wide, and has a sinusoidal outline. It is located at the posterior end of the diamondshaped naso-oral fossa. Tomography data confirm the presence of the naso-oral fenestra, and also the participation of the maxillae in its distal border (a summary of CT procedures is available in the Supporting Information File S1).

The premaxillary surface next to the alveolar margin is smooth and faces slightly ventrally, with an edge clearly separating the ornamented and unornamented surfaces. Six to seven neurovascular foramina are present at this edge, in each premaxilla. The whole alveolar set is projected ventrally relative to the palatine surface of the premaxilla, but neither as evident as in Sarcosuchus or Terminonaris (see Sereno et al., 2001), nor at a lower level than the maxillary alveolar margin. Most alveoli are preserved in the specimen, but the first left and the second right alveoli are partially broken and deformed. There are five alveoli in each ramus, the third and fourth being particularly enlarged, and the fifth the smallest. The fifth premaxillary alveoli are at a more lateral position than the first maxillary alveoli. Overall, the alveoli are weakly procumbent, but the anterior dentition was most likely not, because of the curvature of the crowns. It is possible to recognize two occlusion pits for dentary teeth at the palatal ramus of each premaxilla, immediately posterior to the projected alveolar margin. The medial pit is the deepest, and is posterior to alveoli 1 and 2. The second one is evidently shallower and is located posterior to alveoli 3 and 4.

Maxilla: In dorsal aspect ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ), the maxillae are mostly horizontal laminae, vertically placed only near their lateral end (although this feature is enhanced by the taphonomic dorsoventral deformation). They contact the premaxillae anteriorly, nasals dorsally, and lachrymal and jugal posteriorly. Ventrally, the maxilla probably also contacted the palatine and ectopterygoid.

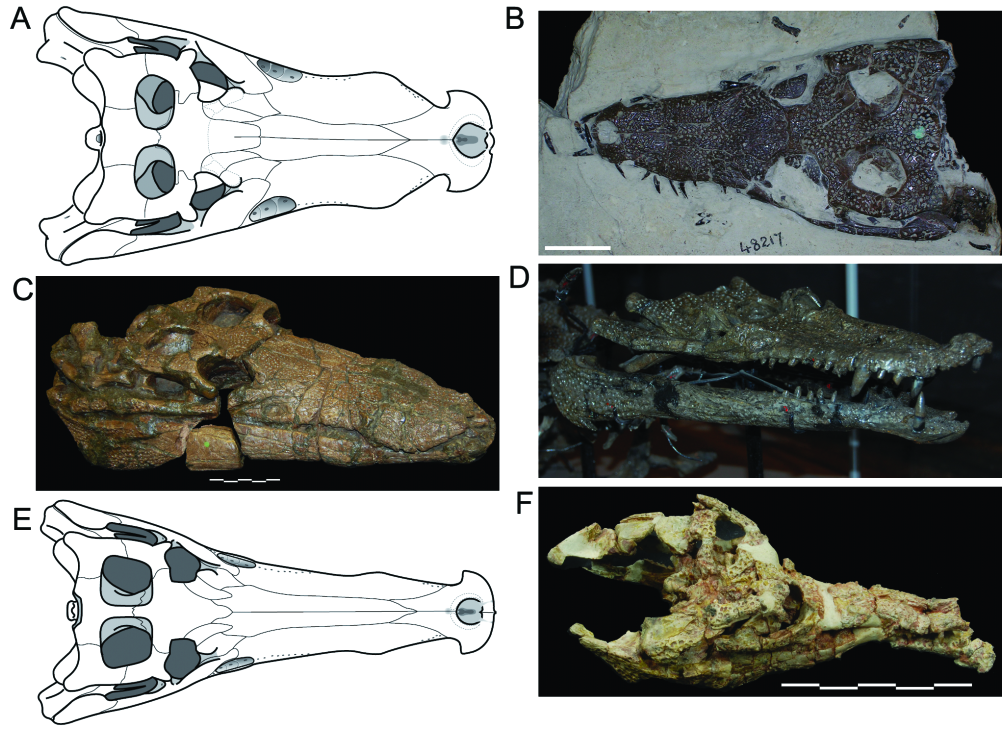

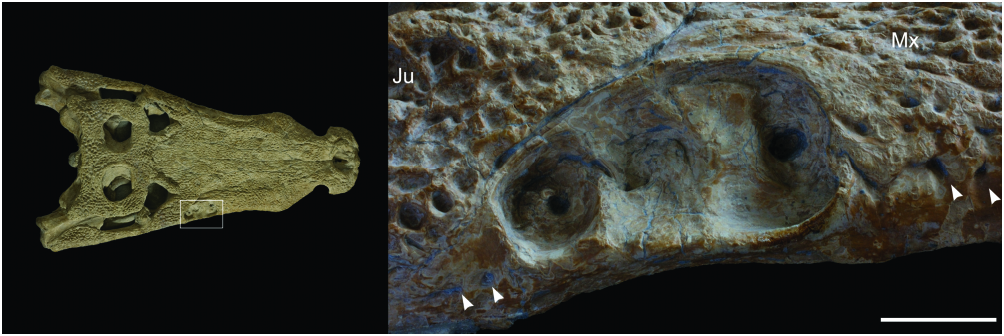

The maxillary (or rostral) depressions occur in a wide range of taxa, including all true Goniopholis , as well as Amphicotylus , Calsoyasuchus and Hulke’s and Hooley’s specimens ( Fig. 3 View Figure 3 ). Similar structures also occur in the basal mesoeucrocodylian Hsisosuchus (Jurassic, China; see Gao, 2001; Peng & Shu, 2005), but apparently extend slightly posteriorly, reaching the jugal ( Gao, 2001). The rostral depressions found in goniopholidids and hsisosuchids are here considered as potentially homologous, because of their similar structure and location. At least in goniopholidids these structures seem to be specialized neurovascular foramina and have a specific morphology that may be related to sensorial or glandular functions ( Andrade, 2009). In DORCM 12154 the morphology of the maxillary depressions ( Fig. 9 View Figure 9 ) is similar to the type of G. simus (BMNH 41098) and the cast material for the Ballerstedt specimens (BMNH R5259–R5262), as well as to G. baryglyphaeus and Hulke’s specimen. The border is evidently well defined throughout the perimeter of the depression and the concave surface has a complex internal structure. At least three internal chambers were present, delimited by shallow and mostly vertical ridges. In DORCM 12154 and most other specimens there is evidence of an enlarged neurovascular opening at the bottom of each chamber ( Fig. 9 View Figure 9 ). Amongst the specimens examined, only the type specimen of G. simus shows, on its right side, what seems to be an incipient fourth chamber, between and above chambers 1 and 2. This seems to be an aberrant condition, as this ‘chamber’ is much shallower, bears no neurovascular opening, and is not present on the left side. Salisbury et al. (1999) reconstruct the maxillary depression of G. simus with five internal chambers, all anteroposteriorly aligned. This, however, is not the condition seen in the holotype, or in the casts of the Ballerstedt specimens, which show only three internal chambers.

Although the chambers are not preserved in Hulke’s specimen, they are clearly visible in Hooley’s specimen (BMNH R3876), also in the number of three. The maxillary depressions are completely absent from Nannosuchus , Denazinosuchus , and Vectisuchus . In the case of Nannosuchus , it is not clear if this absence may be a result of its ontogenetic stage.

Nasals: The nasals ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ) are mostly parallel and elongated, tapering only in the anterior-most section, as in most neosuchians and basal notosuchians. They neither reach the narial opening, nor get close to its border. Instead, the nasals extend forward and contact the premaxillae, separating the posterior ends of these elements. They also contact the lachrymals, prefrontals, and frontal. The nasals widely separate the anterior sections of the frontal and prefrontals, and slightly separate prefrontals from lachrymals. The nasals only contact the medial edge of the lachrymals. The dorsal surface is flat throughout the entire medial contact (character 75), with no evident medial groove (as in thalattosuchians and several notosuchians) or deep trench ( Hsisosuchus , Calsoyasuchus ). The ornamentation is almost exclusively ornamented with pits, lacking the typical elongated grooves of eusuchians. At least two well-defined circular bite marks are visible at mid-rostrum, and a third shallower mark is on the posterior-most section of the right nasal, close to the prefrontal.

Periorbital elements:

The periorbital elements of Goniopholis kiplingi DORCM 12154 were preliminary described, with emphasis in the comparison with other goniopholidid taxa ( Andrade & Hornung, 2011). The following section focuses on the morphology of G. kiplingi itself.

Lachrymals: In DORCM 12154, the lachrymals contact the maxillae, nasals, prefrontals and jugals, and take part in the anterior border of the orbit. As in all other Goniopholis , the lachrymals are relatively wide laminae that extend alongside the rostrum, separating completely the maxilla from the prefrontals. Unlike most other goniopholidids, they do not taper progressive to the anterior end, but end rather abruptly. In DORCM 12154 they are proportionally long (AP/ML of lamina anterior to orbits = 3.15), when compared to all other Goniopholis (AP/ML @ 1.5) and even Hulke’s specimen (AP/ML = 2.85), extending well beyond the anterior-most border of the prefrontals and past the anterior-most tip of the rostral depressions ( Figs 6 View Figure 6 , 8 View Figure 8 ).

Prefrontals: These are relatively small, longer than wide, and well ornamented. The prefrontal contacts the lachrymal, nasal, frontal, and palpebral. The prefrontal certainly does not contact the postorbital in the dorsal part of the orbit, but preservation prevents observation on the ventral surface, where a contact would be possible. The posterior section of the prefrontal extends posteriorly and constitutes the primary medial border of the orbit, as described for G. simus by Salisbury et al. (1999). The prefrontal also provides extensive support for the palpebral ( Andrade & Hornung, 2011).

Frontal: The frontal of DORCM 12154 is a single element, with both sides being completely fused through most of its length (character 132). However, a sagittal suture is retained at the medial line of the anterior process ( Figs 6 View Figure 6 , 8 View Figure 8 ). The main body of the frontal is wide, flat, and has strong ornamentation (characters 133–134). It is well developed posterior to the orbit, where it expands laterally anterior to the supratemporal fenestra and posteriorly into the intertemporal bar. This gives the frontal an overall ‘T-shaped’ outline. Its anterior process is narrow and long, progressing anterior to the orbits and slightly anterior to the prefrontals. The anterior-most border of the anterior frontal process is truncated, with a diminutive intrusion from the nasal, on the medial line.

Dorsally, the frontal contacts the nasals and prefrontals (anteriorly), postorbitals and palpebrals (laterally), and parietal (posteriorly). The frontoparietal contact is medial to the supratemporal fenestra. The frontal posterolateral edge constitutes the full length of the anterior border of the supratemporal fossa, preventing the contact between postorbital and parietal, in dorsal view (although this contact may occur ventral to the frontal, inside the fenestra). The frontal of DORCM 12154 reaches the primary border of the orbit, but its participation is restricted to the posteromedial corner (character 141).

Postorbital: The postorbital is very similar to that of G. simus , bearing a short and robust process dorsal to the bar, anterolaterally orientated. The dorsal surface (and the process) are intensely ornamented. The suture with the frontal is complex, and the contact with the parietal occurs deep inside the supratemporal fossa. Posteriorly, the contact with the squamosal is hardly identifiable, and in dorsal aspect both elements seem to be almost fused. A ventral ramus, clearly distinct from the main body, projects ventrally and contributes to the postorbital bar.

Jugal: The jugal is a triradiate element, with anterior, posterior, and ascending rami. Both anterior and posterior rami are flattened and intensely ornamented. The anterior ramus expands dorsoventrally and anteriorly. The ascending ramus contrasts with the remaining rami, as it is unornamented and mostly cylindrical.

The anterior edge extends dorsomedially, contacting the lachrymal. The dorsal edge is a robust crest, projecting anteriorly and posteriorly. At the anterior end, the crest curves anterolaterally, breaking the contour of the anterior ramus and creating a notch, ending at the dorsolateral surface of the ramus. Posteriorly, the crest bounds the lateral end of the ascending ramus. The jugal participates extensively in the lachrymal fossa ( Fig. 8 View Figure 8 ). Ventrally, the anterior jugal ramus has at leacst two neurovascular foramina next to the maxilla, facing ventrally (character 180). This is shared with other goniopholidids examined, except for Nannosuchus , where the anterior end of the jugal is not well preserved. Such foramina are also present at least in Pholidosaurus , dyrosaurids, Hylaeochampsa , and Bernissartia , and are easily identifiable in all crown crocodylians. Many notosuchians (e.g. Sphagesaurus ) share a similar state, but the foramen is a single enlarged foramen, anteriorly orientated (see Andrade & Bertini, 2008a).

The posterior ramus is not as expanded. It extends to the quadratojugal in a diagonal contact. A vascular foramen is present close to the ventral end of the ascending ramus, on both sides in DORCM 12154, at the anteroventral corner of the laterotemporal fenestra. At least on the left side, the dorsomedial surface of the posterior jugal ramus shows no fewer than two other openings along its dorsomedial surface. This feature is not evident in other taxa, but its presence can be easily masked by preservation.

Postorbital bar: The postorbital bar is a composite structure composed of the descending ramus of the postorbital, ascending ramus of jugal, and often by a dorsal ramus of ectopterygoid. In DORCM 12154 the structure is poorly preserved on both sides following taphonomic dorsoventral deformation. Nonetheless, it is possible to recognize that it was subdermic and not ornamented, robust, and cylindrical (subcircular cross-section). The area of the jugal- postorbital suture is destroyed, and it is impossible to identify the contact. As the dorsal ramus of the jugal projects posteromedially on both sides in DORCM 12154, the inclination of the bar is perfectly identifiable. The left ectopterygoid, as preserved, shows that it took part in the medial face of the bar, but it is not possible to recognize whether it contacted the postorbital inside the bar or not. However, it was most likely similar to the condition found in Hulke’s specimen, where the ectopterygoid extends dorsally, taking part in the medial face of the bar, even reaching the ventral ramus of the postorbital.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to confirm the presence of a vascular opening on the postorbital close to the dorsal end of the bar, because of poor preservation of the area in DORCM 12154. However, the surface immediately posterior to the dorsal end of the bar is smooth and depressed, and it is quite possible that vascular foramina were present in that fossa. A similar situation is seen in Hulke’s specimen, which shows an even deeper fossa.

Palpebrals: Palpebrals were not preserved, but there are evident scars for the attachment of an anterior (single) palpebral. These scars are deep, long, and are preserved on both sides in the orbital margin. Each scar ranges from the anteromedial to the posteromedial border of the orbit, encompassing most of the lateral surface of the upper periorbital ridges. These should have been ‘delta-like’, massive, although not nearly similar to the wide palpebrals found in baurusuchids. Amongst goniopholidids, only Nannosuchus and Hulke’s specimen are reported to have palpebrals preserved ( Hulke, 1878; Joffe, 1967), which are fairly consistent with the delta-like profile inferred for DORCM 12154, although this structure is evidently more gracile in Nannosuchus . Hooley’s and Dollo’s specimens have narrower and more elongated palpebrals, robust and integrated to the orbital border. In DORCM 12154, as in most other goniopholidids, there is no evidence of a posterior palpebral. The morphology of the posterior orbital border and comparison with related forms show that its presence is unlikely.

In the absence of palpebrals, the orbits of DORCM 12154 assume a triangular profile. Overall, the morphology of the orbit is similar to G. baryglyphaeus and most G. simus , but specimens of this later taxon show an intraspecific variability, with the orbit being either triangular or subcircular ( Andrade & Hornung, 2011).

Skull roof

The skull roof is wide, flat, and intensely ornamented. Pits composing the ornamentation tend to be larger at the medial line of the skull roof, and never elongated (see Buffrénil, 1982), therefore not forming the grooves commonly seen in eusuchians. The intertemporal bar is relatively wide, showing a double concave profile, contrasting with G. simus , where the intertemporal bar has straight and parallel lateral borders.

Overall, the lateral margins of the skull roof (= upper temporal bars) are parallel in DORCM 12154, as in most goniopholidids (character 148). The temporal bars are strongly sinusoidal (character 149), as in G. simus , G. baryglyphaeus , and Nannosuchus , contrasting with the straight profile seen in Hulke’s specimen, most North American forms, pholidosaurids, dyrosaurids, and possibly Siamosuchus . The sinusoid profile is also shared by Amphicotylus (D. Pol, pers. comm. 2010; contra Mook, 1942). The bar anterior to the supratemporal fossa is broad, almost as wide as the bar posterior to the fossa.

Supratemporal fenestrae and fossae: In DORCM 12154, the left fossa shows better preservation. It is subcircular to polygonal, with straight anterior and posterior margins, angled lateral margin, and a convex round medial margin. The lateral margin is formed by the intersection of two straight margins, which meet at an angle (~80°) in the middle of the supratemporal bar. From the anterolateral to posteromedial borders (postorbital, squamosal, and parietal), the internal margin projects slightly over the fenestra. Most of the anterior to medial margins (frontal to anterior end of parietal) do not project at all, but are acute and well defined. However, in the anteromedial corner, the transition from the fossa to the skull table is somewhat smoother. The same morphology is present in other Goniopholis specimens, as well as in several other related forms studied (i.e. Nannosuchus , Hulke’s specimen, Pholidosaurus , Sarcosuchus ).

Parietal and squamosal: The parietal of DORCM 12154 is single, well sculpted, and composes all the posteromedial margin of the skull table. Its posterior border is well preserved and mostly straight, not projecting significantly over the occipital surface. The suture with the frontal is evident at the middle of the intertemporal bar, and is mostly ‘v’-shaped (concavity facing posteriorly).

The squamosal contacts the parietal medial to the supratemporal fenestra. The contact with the postorbital is not evident, but is likely to be lateral to the external angle of the supratemporal fenestra. In dorsal view, the element is flattened, intensely ornamented, and extends posterolaterally over the quadrate, as an ornamented horizontal lobe (giving the skull table its sinusoid profile). There is, however, no unsculpted lamina departing from this lobe and reaching the quadrate, or from the lateral edge of the supratemporal bars.

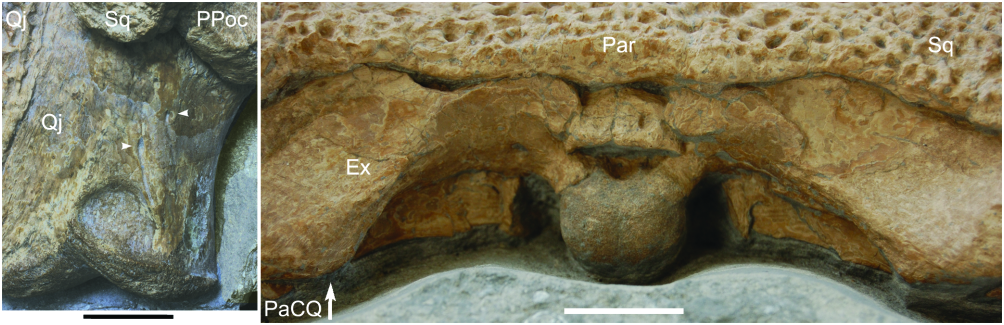

Quadratojugal: The quadratojugal is firmly attached to the jugal and quadrate, and the sutures with these elements are difficult to recognize. Nonetheless, the contact with the posterior jugal ramus is slightly displaced, showing that the suture is ventral to the laterotemporal fenestra and orientated anterodorsally- posteroventrally. As in most mesoeucrocodylians, the lateral end is intensely ornamented. The suture with the quadrate curves laterally near the condyles, next to the ornamented surface of the quadratojugal, and does not reach the articular surface. The unornamented ascending process narrows as it progresses medially. Its anterior edge probably held a long quadratojugal spine as in G. simus , but the area is not preserved in DORCM 12154.

Quadrate: The quadrate is robust, and is posterodistally orientated ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). The proximal end of the quadrate is partially covered by the skull table on both sides, as a result of the dorsoventral deformation of the skull, obliterating the tympanic area and preventing observation of possible structures (i.e. preotic siphoneal foramen). CT data show that the quadrate is massive in structure, and is neither perforated nor internally pneumatic (a characteristic restricte d to certain notosuchians and basal groups of crocodylians). The quadrate distal condyles are level with each other, and are positioned at a more posterior position than the occipital condyle. The posteromedial margin is steep throughout, and separated by the dorsal surface by a smooth and poorly defined edge, similar to Pholidosaurus . In opposition, Hulke’s specimen, G. simus , and at least G. stovalli have an acute edge, separating the dorsal and the posteromedial surfaces.

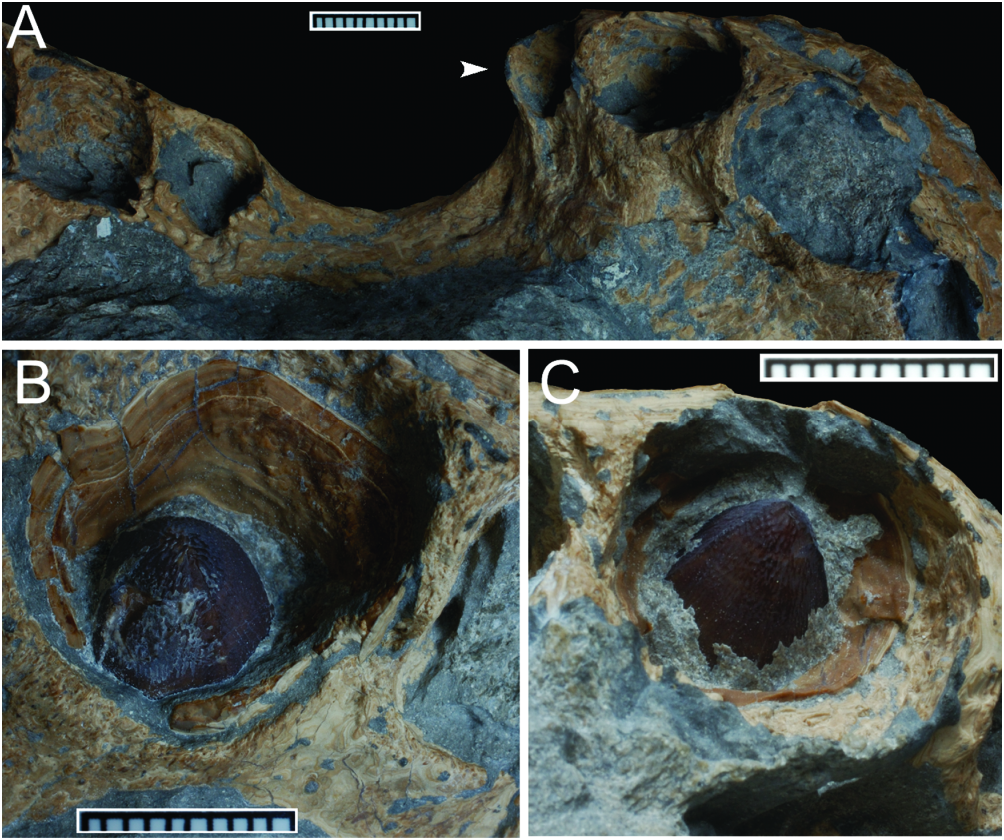

As for most crocodylians, including modern forms, DORCM 12154 has a foramen aerum on the dorsomedial face of the quadrate, next to the quadrate condyle. However, a second opening is present at the dorsal surface of the quadrate, at a short distance (laterally and posteriorly) from the ‘primary’ opening of the foramen aerum ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ), a feature that is preserved on both sides and is clearly visible. This is unexpected, because crocodylomorphs only possess one foramen aerum on each quadrate, being either on the dorsomedial face (most crocodilians so far described, including Sphagesaurus and Sunosuchus ) or the dorsal surface (alligatoroids, mostly; see Brochu, 1999), and so far only DORCM 12154 shows this condition.

Occipital surface

The observation of the supraoccipital in DORCM 12154 is constrained by the dorsoventral deformation of the skull ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ). However, it is still possible to recognize that the element does not reach the skull roof.

The exoccipitals ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ) are mostly well preserved, and the only damaged area is dorsal to the foramen magnum, where both laminae meet. In this section, the exoccipitals loosened as a single lamina from their main body, and became horizontal. Consequently, the surface actually faces dorsally, rather than posteriorly, resembling the horizontal and posteriorly projecting lamina that covers the foramen magnum in Hsisosuchus , although in DORCM 12154 this is clearly an artificial condition caused by the dorsoventral deformation.

The lateral edges of the exoccipitals (= paraoccipital processes) are evident but they do not extend lateral to the skull roof or the squamosals. Their morphology is very similar to G. simus , G. baryglyphaeus , Pholidosaurus , Sarcosuchus , Bernissartia , and the specimens noted by Hulke (1878), Dollo (1883), and Hooley (1907). The ventral edge of the paraoccipital process projects ventrally, shielding the distal end of the cranioquadrate canal, which is not evident on the occipital surface. In G. simus and G. baryglyphaeus the cranioquadrate canal is only partially enclosed (dorsally, medially, and ventrally), but laterally exposed, and runs as a sulcus from the auditory meatus to the occipital surface ( Salisbury et al., 1999; Schwarz, 2002). A laterally exposed cranioquadrate canal is also present at least in the Hulke specimen, and some non-goniopholidid neosuchians (e.g. Allodaposuchus , Hylaeochampsa ; see Delfino et al., 2008). In DORCM 12154 the area is obliterated due to dorsoventral deformation, but preliminary observation of the CT data seems to corroborate the same morphology for this specimen. In any case, it is evident that the paraoccipital process of DORCM 12154 does not contact the quadrate extensively, lateral to the passage (character 308).

Palate, choanae, and pterygoid

Although the ventral side of the specimen remains mostly hidden by matrix, and detailed description must await proper analysis of CT data, it is possible to present preliminary information on the palatal structures. Further information on the CT data on the palate, including a simplified reconstruction, is available in the Supporting Information File S1.

The secondary palate of DORCM 12154 is fully formed, with palatine rami of premaxillae and maxillae present and in contact on the medial line. The nasopharyngeal duct is complete and opens in the posterior half of the skull, between the palatines and pterygoids. There is no evidence of a ventral exposure of the vomer in the palate. As in most mesoeucrocodylians, including related forms such as Hulke’s specimen, the maxillary palate progresses anteriorly to the premaxillary palate. This contrasts with the condition found in eusuchians, where the premaxillary palate progresses posteriorly over the maxillary palate. Although not perfectly preserved, the internal naris has an overall morphology similar to that in G. simus , where the choanal opening is ample, longer than wide, and with a lanceolate profile ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ).

The naso-oral fenestra (= incisive foramen, foramen incisivum) is present and fully open. The passage is deep and the surrounding fossa resembles closely that in G. simus (although in G. simus the fossa does not form a fenestra; see Salisbury et al., 1999). As in most mesoeucrocodylians, the palatine rami of the maxilla take part in the posterior border of the naso-oral fenestra.

Maxillo-palatine fenestrae (= palatine fenestrae; Gasparini, 1971) are known from a series of taxa assigned to Goniopholididae , such as Eutretauranosuchus , Sunosuchus , and Calsoyasuchus , where they are also referred to as the ‘primary choanae’ (as in Tykoski et al., 2002). They are however absent from DORCM 12154, as in G. simus and Hooley’s and Hulke’s specimens.

Unfortunatelly, it is impossible to verify precisely the relationships amongst palatine, ectopterygoid and pterygoid, but it seems clear that DORCM 12154 had neither a palatine- ectopterygoid contact, nor a palatine bar, as in all neosuchians. Therefore, the pterygoids reach the distal end of the suborbital fenestra, separating the ectopterygoids from the palatines.

Dentition

The dentition of DORCM 12154 was almost entirely lost prior to burial, and only a few unerupted crowns remain preserved and accessible. Although most of the ventral side of the specimen is covered by matrix, the alveolar margin was exposed on the right side, showing the overall distribution of teeth ( Fig. 11 View Figure 11 ). Further, a small section of the left side was also exposed near the ectopterygoid- jugal contact, showing the last few alveoli.

There were five alveoli in the premaxilla, the third and fourth being largest, and the fifth the smallest. Another 19 alveoli are present in the maxilla, the fourth and fifth being largest, but with a second wave of large teeth at about the 11 th alveolus. This comprises a total of 24 upper teeth. Alveoli vary in size along the premaxilla and maxilla, as expected for a goniopholidid ( Table 1). The maxilla has two ‘waves’ of enlarged teeth (festooning), but its lateroventral margin does not project ventrally/laterally, coincident with the second set of enlarged alveoli. The morphology agrees with G. simus and G. baryglyphaeus , and contrasts with the festooning seen in peirosaurids and related forms, and also with Bernissartia and Crocodylus , where the feature is particularly evident. Although the mandible was not preserved, the dentary most likely supported 20–24 teeth, with a large tooth at the symphysis occluding in the premaxilla- maxilla notch. The first dentary tooth was probably large, fitting into the occluding pits seen in the premaxillae, near the medial line. The fifth premaxillary alveolus is positioned at a more lateral position than the first. There is a considerable gap between both teeth at the premaxilla- maxilla notch. Although premaxillary teeth seem to have been at the same level as the maxillary teeth before the flattening of DORCM 12154, it is clear that the premaxillary dentition projects ventrally relative to the palate.

Only the third premaxillary (left side) and fourth maxillary (right side) crowns are preserved and exposed, although partially ( Fig. 11 View Figure 11 ). As these are non-erupted teeth, wear or damage from use did not affect these crowns, which are well preserved. They are very similar to crowns described and attributed to G. simus , G. baryglyphaeus , Hulke’s and Hooley’s specimens, and evidently more robust than the teeth of Nannosuchus . The crown itself is bulbous, as it is slightly inflated, with an acuminate apex (although the anterior tooth is slightly more slender when compared with the posterior one). The crown is subcircular in cross section, without evident lateral compression, but the lingual and labial surfaces are asymmetric. The labial face is strongly arched, whereas the lingual is not as much. Enamel ornamentation is present on both lingual and labial surfaces, in the form of basi-apical ridges. These are well defined, conspicuous, and closely packed, but low. Overall, the ornamentation is non-anastomosed at least at the base and mid-crown, whereas apically there is a reasonable degree of anastomosis. A distinct keel runs on mesial and distal faces of the crown. As the anastomosed ornamentation extends toward the apex and keel, a crenulated surface is formed, leading to a false-ziphodont condition. This pattern of tooth crown morphology seen in DORCM 12154 ( Fig. 11 View Figure 11 ) is very similar to the one found in G. simus and G. baryglyphaeus , but is also consistent with the crown morphology seen in taxa from other related groups, such as Pholidosaurus and Machimosaurus .

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |