Neacomys Thomas, 1900

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0090(2001)263<0003:TMOPFG>2.0.CO;2 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B69D69-FF82-3738-8578-FE4AFF76F90A |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Neacomys Thomas |

| status |

|

The Neotropical spiny mice of the genus Neacomys have never been revised, and many aspects of their specieslevel taxonomy have long been problematic. The identification of spiny mice from the Guiana subregion of Amazonia is a case in point: although these have traditionally been identified as N. guianae (e.g., by Anthony, 1921a; Tate, 1939; Carvahlo, 1962; Husson, 1978; Genoways et al., 1981; Guillotin, 1982; Malcolm, 1990; Voss and Emmons, 1996), the diagnostic morphological characters and geographic range of this species are not documented in the literature. In his original description, Thomas (1905: 310) compared N. guianae only with N. spinosus (Thomas, 1882) , stating that the new species was very similar but ‘‘conspicuously smaller’’. However, size does not distinguish guianae from such other diminutive forms as tenuipes Thomas (1900) , pusillus Allen ( 1912) , and pictus Goldman ( 1912) . Musser and Carleton ( 1993) listed N. guianae , N. pictus , N. spinosus , and N. tenuipes (including pusillus ) as valid species, but the recent description of two additional species from western Amazonia ( N. minutus and N. musseri ), together with sequence comparisons showing high levels of genetic differentiation among several undescribed mtDNA clades of spiny mice, suggests that the genus is much more diverse than previously recognized (Patton et al., 2000).

In order to identify our Paracou vouchers, we examined original descriptions of all nominal taxa of Neacomys , and we examined holotypes or paratypes of all the smaller named forms ( guianae , minutus , musseri , pictus , pusillus , tenuipes ). We tried to locate every Guianan Neacomys specimen currently housed in North American and European museums, and we measured representative series to document morphometric variation within and among species. The results of our comparisons indicate that at least three distinct species are present in the Guiana subregion of Amazonia, of which two are new and occur sympatrically at Paracou. Because the very brief diagnoses of Neacomys provided by Thomas (1900), Gyldenstolpe (1932), and Ellerman ( 1941) are now insufficient as a basis for taxonomic inference, we rediagnose the genus here.

EMENDED DIAGNOSIS OF NEACOMYS : Small oryzomyines (sensu Voss and Carleton, 1993: 31) with coarsely grizzled yellowish, reddish, or grayishbrown dorsal fur containing short, grooved spines in addition to conventional guard hairs and underfur; ventral fur similar in composition to dorsal fur, but shorter and always contrastingly colored; pinnae small, dark, and sparsely haired; mammae eight in inguinal, abdominal, postaxial, and pectoral pairs; hindfoot with outer digits (I and V) much shorter than three middle digits (claw of dI not extending beyond middle of first phalange of dII, claw of dV not extending beyond first interphalangeal joint of dIV); claws of pedal digits II–V provided with ungual tufts of long whitish or silvery hairs that exceed the claws in length; tail sparsely haired (appearing naked except under magnification) with prominent epidermal scales in annular series, sometimes with a thin terminal pencil but never with a conspicuous tuft of long hairs at tip. Skull with prominently beaded supraorbital margins; interparietal large; palate long and wide, with prominent and often complex posterolateral pits flanking anterolateral margins of mesopterygoid fossa; parapterygoid fossae shallow (never deeply excavated above level of palate); alisphenoid strut absent (except as rare, usually unilateral variant); carotid circulation includes large stapedial artery (pattern 1 or 2 of Voss, 1988); tegmen tympani not overlapping posterior margin of squamosal (posterior suspensory process of squamosal absent); subsquamosal fenestra sometimes small but always present and usually patent. Upper incisors small, narrow, and opisthodont (never orthodont or proodont); lower incisor root contained in prominent capsular process on lateral surface of mandible; molars small and pentalophodont (mesolophs on M1 and M2 always well developed and fused to mesostyle on labial cingulum); M1/m1 without accessory roots.

Neacomys dubosti , new species Figures 36 View Fig , 37 View Fig , 38B View Fig , 39A, 39C View Fig , 43 View Fig

TYPE MATERIAL AND TYPE LOCALITY: The holotype, AMNH 267569, an adult female preserved as a fluid specimen with the skull extracted and cleaned, was collected at Paracou by R. W. Kays (original number: RWK 9) on 7 August 1993. No other material is known from the type locality, but all of the additional specimens we examined from French Guiana and Amapá are hereby designated as paratypes.

DISTRIBUTION AND SYMPATRY: Based on specimens we examined, Neacomys dubosti occurs in French Guiana, Amapá ( Brazil), and southeastern Surinam (fig. 35). In Surinam, N. dubosti has been collected sympatrically with N. guianae (at the Sipaliwini Airstrip, Nickerie District), and it occurs sympatrically with another new species in French Guiana and Amapá (see the next account, below).

ETYMOLOGY: The specific epithet honors Gérard Dubost for his many contributions to knowledge of mammalian ecology and natural history in the lowland rainforests of French Guiana and Gabon. We are also grateful for his original suggestion of Paracou as the site for our mammal inventory, and for his subsequent support and advice throughout the course of our fieldwork there.

DIAGNOSIS: A small species of Neacomys (measurements in table 18) distinguished from other diminutive congeners by its short, usually unicolored tail; moderately short rostrum flanked by relatively shallow zygomatic notches; broad and strongly convergent interorbital region with highly developed, shelflike supraorbital beads; broad and distinctly inflated braincase; short, convexsided incisive foramina; carotid circulation pattern 1; M1 with undivided anterocone; mesoloph of M1 with moreorless symmetrical connections to protocone and hypocone; persistently tubercular molar cusps; and a distinctive range of craniometric variation.

MORPHOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION: Dorsal pelage coarsely grizzled tawny or reddish brown, somewhat paler along sides due to middorsal concentration of darktipped spines; ventral fur abruptly paler, sometimes pure white from chin to anus (e.g., CM 76840, MNHN 1983.412, USNM 46182), but more commonly suffused to a greater or lesser extent with buff or orange; ventral hairs usually pale to roots, very rarely with indistinctly gray bases (e.g., USNM 461571, 461590); broad lateral line of clear buff or orange separating dorsal and ventral pelage present in all specimens examined. Superciliary, genal, and some mystacial vibrissae extend behind pinnae when laid back against head. Dorsal surface of manus and pes covered by short pale fur in most specimens, but hairs over central metapodials sometimes indistinctly darker than those on digits and out er metapodials; claw of pedal digit I extending about onehalf length of phalange 1 of adjacent digit II; claw of pedal digit V extending to but not beyond end of first phalange of adjacent digit IV; small but distinct hypothenar (lateral tarsal) plantar pad present on hindfoot of one fluid specimen (this trait is difficult to score reliably on dried skins). Tail about as long as combined length of headandbody; almost always unicolored (dark above and below), but occasionally indistinctly paler ventrally at base (e.g., CM 76842, MNHN 1972.641); with small caudal scales (21 rows/cm near base of tail in one

TABLE 18 Measurements (mm) and Weights (g) of Neacomys dubosti

fluid specimen) forming relatively narrow annulations.

Skull with moderately short, tapering rostrum flanked by relatively shallow zygomatic notches; interorbital region broad, with strongly convergent lateral margins; supraorbital beads highly developed, projecting as small shelves over posterior orbits and continuing onto braincase as low temporal crests; braincase inflated, conspicuously domed, and very broad behind squamosal zygomatic processes. Incisive foramina relatively short (averaging about 57% of diastemal length), usually with distinctly convex lateral margins; zygomatic plate relatively narrow; carotid circulation with welldeveloped supraorbital ramus of stapedial artery (occupying squamosalalisphenoid groove and sphenofrontal foramen; pattern 1 of Voss, 1988); subsquamosal fenestra smaller than postglenoid foramen but always distinct and patent; auditory bullae usually flaskshaped, tapering gradually from tympanic ring to unconstricted bony eustacian tubes.

First maxillary molar with undivided anterocone; anteroloph of M1 seldom distinct, usually fused labially with anterocone (anteroflexus usually distinguishable only as persistent internal fossette); mesoloph of M1 straight and slender, projecting labially from symmetrically Yshaped junction with median mure, without disproportionate connection to hypocone; principal labial cusps (paracone, metacone) slightly reduced in size relative to lingual cusps (protocone, hypocone); principal cusps persisting as distinctly tubercular elements with moderate wear.

KARYOTYPES: Two specimens from Amapá (MNHN 1972.640, 1972.641) karyotyped by M. Tranier had diploid counts of 2N=62 chromosomes (as recorded on skin labels).

VARIATION: The three geographic samples at hand, from Surinam, French Guiana, and Amapá (table 18), are very similar in most qualitative and quantitative characters. Instead, most of the variation in the material we examined (e.g., as noted parenthetically in the preceeding description) occurs as individual differences within local populations. However, resemblances are strongest between French Guianan specimens and a large series from the Serra do Navio in Amapa´, Brazil. By contrast, our few Surinamese examples have slightly narrower molars and interorbital regions, and their supraorbital beads appear somewhat less developed as projecting shelves.

COMPARISONS: Neacomys dubosti could potentially be confused with two previously described congeners from northern South America— N. tenuipes and N. guianae —in addition to N. paracou , another new species described below. Selected qualitative contrasts among these four taxa are summarized in table 19, descriptive univariate statistics for measurements of representative series are provided in table 20, and the results of multivariate morphometric analyses are represented in figure 40 and table 21. More detailed, characterbycharacter comparisons are deferred to the next account. Patton et al (2000) recently described additional species of smallbodied Neacomys from western Brazil, but those bear no close resemblance to either N. dubosti or N. paracou and so are not treated in these accounts.

REMARKS: At least some of the specimens previously reported in the literature as Neacomys guianae by Carvalho (1962), Genoways et al. (1981), and Guillotin (1982) are probably referable to N. dubosti , but those authors did not provide the museum catalog numbers of relevant voucher material and we are therefore unable to associate confident species identifications with their observations.

OTHER SPECIMENS EXAMINED: Brazil — Amapa´, Serra do Navio (USNM 461563– 461569, 461571, 461572, 461574–461576, 461579–461582, 461584, 461588, 461590– 461595, 461601, 461604, 461612); no other locality data (MNHN 1972.640, 1972.641). French Guiana —Cacao (MNHN 1983.426, 1986.534, 1986.535, 1986.537, 1986.538, 1986.541–1986.545), Camopi (MNHN 1983.403), Iracoubo (MNHN 1983.409), Piste St.Élie km 16 (MNHN 1986.876, 1986.877), Saül (MNHN 1983.405– 1983.407, 1983.422, 1983.423, 1983.425), St.Eugène (MNHN 1995.3226–1995.3229, 1998.1835, 1998.1839), TroisSauts (MNHN 1982.629, 1982.630, 1983.410, 1983.412, 1983.414–1983.416). Surinam — Marowijne, Oelemarie (CM 76835–76837, 76839– 76843); Nickerie, Sipaliwini Airstrip (CM 76846).

FIELD OBSERVATIONS: Our single specimen of Neacomys dubosti from Paracou was taken in a pitfall trap in creekside primary forest.

Neacomys paracou , new species Figures 36 View Fig , 37 View Fig , 39B, 39D View Fig , 42B View Fig , 43 View Fig

TYPE MATERIAL AND TYPE LOCALITY: The holotype, MNHN 1995.1020, an adult male preserved as a complete skeleton, was collected at Paracou on 23 August 1993 by Roland W. Kays (original number: RWK 30). All of the additional specimens we examined from Paracou (see Specimens Examined, below) are hereby designated as paratypes.

DISTRIBUTION AND SYMPATRY: Specimens that we refer to Neacomys paracou are from French Guiana, Surinam, Guyana, eastern Venezuela ( Bolívar state), and Guianan Brazil (north of the Amazon and east of the Rio Negro) (fig. 41). Based on these records it would be reasonable to expect that the species occurs throughout the Guiana subregion of Amazonia, but we have not seen any material from the Amazonas federal territory of Venezuela. Neacomys paracou has been collected sympatrically with N. guianae in Guyana (at Kartabo), and with N. dubosti in Surinam (Oelemarie), French Guiana (Cacao, Paracou, Saül, St.Eugène), and Amapá (Serra do Navio).

ETYMOLOGY: The species is named for our study area, treated as a noun standing in apposition to the generic name.

DIAGNOSIS: A small species of Neacomys (measurements in table 22) distinguished from other likesized congeners by its very short outer pedal digits; short, unicolored tail; short rostrum flanked by relatively deep zygomatic notches; broad and usually strongly convergent interorbital region with well

TABLE 19 Diagnostic Qualitative Comparisons among Four Species of Neacomys

developed and often shelflike supraorbital beads; narrow, uninflated braincase; long, parallelsided incisive foramina; carotid circulation pattern 1; M1 with narrow, undivid ed anterocone; mesoloph of M1 stout, often curving from and disproportionately connected to hypocone; principal molar cusps quickly worn to enamel loops, not persistently tubercular; and a distinctive range of morphometric variation.

TABLE 20 Comparative Measurements (mm) and Weights (g) of Representative Series of Four Species of Neacomys

MORPHOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION: Dorsal pelage coarsely grizzled tawny or reddishbrown, somewhat paler along sides due to middorsal concentration of darktipped spines; ventral fur abruptly paler, often pure white from chin to anus, but sometimes with orange pectoral markings (e.g., AMNH 266548), or broadly suffused with orange (e.g., CM 76845); ventral hairs pale to roots in most specimens (rarely with indistinctly gray bases between the fore and hindlegs; e.g., AMNH 266545); broad lateral line of clear buff or orange separating dorsal and ventral pelage in many specimens, but lateral line narrow or absent in others (e.g., AMNH 266542, CM 76844, MNHN 1986.285). Superciliary and genal vibrissae extending behind pinnae when laid back alongside head, but mystacial vibrissae consistently shorter, not extending much if at all behind pinnae on properly madeup skins. Dorsal surface of manus and pes covered with short pale fur, often with indistinctly darker markings over central metapodials; claw of pedal digit I extending less than onehalf length of phalange 1 of adjacent digit II; claw of pedal digit V extending no more than threefourths length of phalange 1 of adjacent digit IV; hypothenar (lateral metatarsal) plantar pad small but distinct in some specimens, indistinct or absent in others. Tail about as long as, or a little shorter than, combined length of headandbody; unicolored (dark above and below), rarely indistinctly paler ventrally at base (e.g., AMNH 266548); with large caudal scales (15–18 rows/cm near the base of the tail in nine fluid specimens) forming coarse and conspicuous annulations.

Skull with very short rostrum flanked by moderately deep zygomatic notches; interorbital region broad and usually strongly convergent; supraorbital beads well developed, often projecting as small shelves over posterior orbits and continuing onto braincase as low temporal crests; braincase relatively narrow in most specimens and not conspicuously inflated. Incisive foramina relatively long (averaging about 65% of diastemal length) and narrow, usually with moreorless parallel lateral margins; zygo matic plate relatively broad; carotid circulation with welldeveloped supraorbital ramus of stapedial artery (occupying squamosalalisphenoid groove and sphenofrontal foramen; pattern 1 of Voss, 1988); subsquamosal fenestra often very small and sometimes occluded by internal flange of petrosal; auditory bullae usually globular, with spherical tympanic capsules and abruptly constricted bony eustacian tubes.

First maxillary molar typically with very narrow, undivided anterocone; anteroloph of

TABLE 21 Results of Linear Discriminant Function Analysis of Craniodental Measurement Data from Four Neacomys Species Samplesa

M1 usually indistinct (fused with anterocone) even on unworn teeth; mesoloph of M1 very prominent (mesoloph/mesostyle complex sometimes rivalling paracone and/or metacone in size) and disproportionately connected to hypocone by median mure, arising anterolabially from that cusp in an uninterupted curve on most unworn teeth; principal labial cusps (paracone, metacone) distinctly smaller than lingual cusps (protocone, hypocone); all principal cusps quickly worn down to enamel loops, not persisting as distinctly tubercular elements in most adult dentitions.

KARYOTYPES: Two specimens of Neacomys paracou karyotyped by M. Tranier from ‘‘Cayenne, Rte. de Cacao’’, French Guiana (MNHN 1983.419, 1983.420) and another from Saül (MNHN 1983.418) had diploid counts of 2N=56 chromosomes (recorded on skin tags). The same diploid counts were obtained by E. Bach from chromosomal preparations of two Venezuelan specimens (AMNH 257270, MNHLS 8064) that were part of the series from San Ignacio Yuruaní originally misidentified by Voss (1991: table 23) as N. tenuipes .

VARIATION: Samples that we refer to Neacomys paracou are remarkably similar in morphological characters across a very large geographic range. The most metrically divergent series consists of three Venezuelan examples (from San Ignacio Yuruaní in eastern Bolívar state; table 22), which have longer hindfeet, slightly larger molars, and slightly longer rostrums than most Paracou specimens; broad overlap between these samples in most measured dimensions (together with the lack of other distinguishing characters), however, suggest that they are not specifically distinct. Specimens from two other geographically outlying samples (in the Brazilian states of Amazonas and Para´; measurements not tabulated) have less welldeveloped supraorbital beads than most topotypical specimens but do not appear to be morphometrically divergent or remarkable in other qualitative respects.

COMPARISONS: Neacomys paracou requires close comparisons with three other small species from northern South America, N. dubosti , N. guianae , and N. tenuipes . Of these, dubosti , guianae , and paracou occur in the Guiana subregion of Amazonia, where they have been collected sympatrically in all pairwise combinations (but never all three together). Neacomys tenuipes does not occur in the Guiana subregion, but its nomenclaturally crucial status as the oldest named species of small spiny mice compels us to include it in this comparative analysis.

( A, C; USNM 461580) and N. paracou ( B, D; USNM 461609).

Although all small species of spiny mice are similar in most external characters, the morphology of the hindfoot and the tail can be used in combination to provide tentative field identifications. In tenuipes and dubosti , the outer pedal digits (dI and dV) are relatively long: the claw of dI extends almost or fully half the length of the first phalange of dII, and the claw of dV extends almost or fully to the end of the first phalange of dIV. By contrast, the claw of dI does not extend much beyond the base of the first phalange of dII in guianae and paracou , and the claw of dV in these two species does not extend more than about half the length of the first phalange of dIV. These proportional differences are easiest to see in fresh material, or in fluids, where the digits can be straightened and freely manipulated; in carelessly madeup skins (with twisted or bent toes), however, digital proportions can be hard to evaluate.

In specimens measured by the American method (total length and tail length [dorsal flexure to fleshy tip] measured in the field; headandbody length calculated by subtraction), the tail is consistently longer than the headandbody by a substantial amount (the ratio LT/HBL averaging about 115%) in tenuipes , but in the other three species the tail is about the same length as the headandbody, on average. Unfortunately, the ratio of tail to headandbody cannot be compared meaningfully among specimens measured by different protocols, and many specimens of Neacomys are captured with bobbed tails. Nevertheless, the contrast in tail length is visually obvious when comparing series of skins of tenuipes with those of dubosti , guianae , and paracou .

The tail is distinctly bicolored (dark above, pale below), at least near the base, in most specimens of tenuipes , but most specimens of dubosti and paracou have unicolored (all dark) tails. Unfortunately, the few available skins of guianae are too variable to characterize the species with confidence for this trait: whereas the type and two Surinamese specimens have tails that are distinctly bi colored at the base, four other specimens have indistinctly bicolored or unicolored tails.

In visual comparisons of dried skins, the

minimum convex polygons enclosing all referred specimens. Together, the first and second principal components accounted for 65% of the total variance in analyses A–D, 70% in analysis E, and 69% in analysis F. Species scores did not differ significantly on subsequent components (after the second) in analyses A, B, D, E and F, but the scores of N. dubosti and N. tenuipes differed significantly ( p K 0.01 by 1way ANOVA) on the fourth component (not shown) in analysis C.

TABLE 22 Measurements (mm) and Weights (g) of Neacomys paracou

caudal scales appear to be larger and to form coarser annulations in paracou than in the other three species, but this difference is hard to quantify because tails are stretched to varying degrees when skins are stuffed. Although we counted the number of scale rows per centimeter near the base of the tail on fluid specimens, only a few fluids were available for most species. Nevertheless, our data suggest that this character might be useful for field identifications: whereas nine adult fluid specimens of paracou from the type locality had 15–18 (mean = 16) scale rows/cm, the fluid holotype of dubosti had 21 rows/cm. We were not able to examine any fluid specimens of tenuipes or guianae .

We assessed species differences in cranial morphology by visual comparisons supplemented by measurements of representative samples (table 20). Although most statistical details of our morphometric analyses are necessarily omitted from this faunal report, the scatter plots in figure 40 depict patterns of multivariate divergence revealed by six pairwise principal components ordinations, and the matrix in table 21 summarizes the outcome of a linear discriminant function analysis with all species treated simultaneously. Both methods indicate that these taxa are craniometrically distinct in all pairwise combinations with the exception of dubosti and tenuipes , which have partially overlapping multivariate distributions. The following are the principal points of quantitative and qualitative cranial difference based on our visual and analytic comparisons.

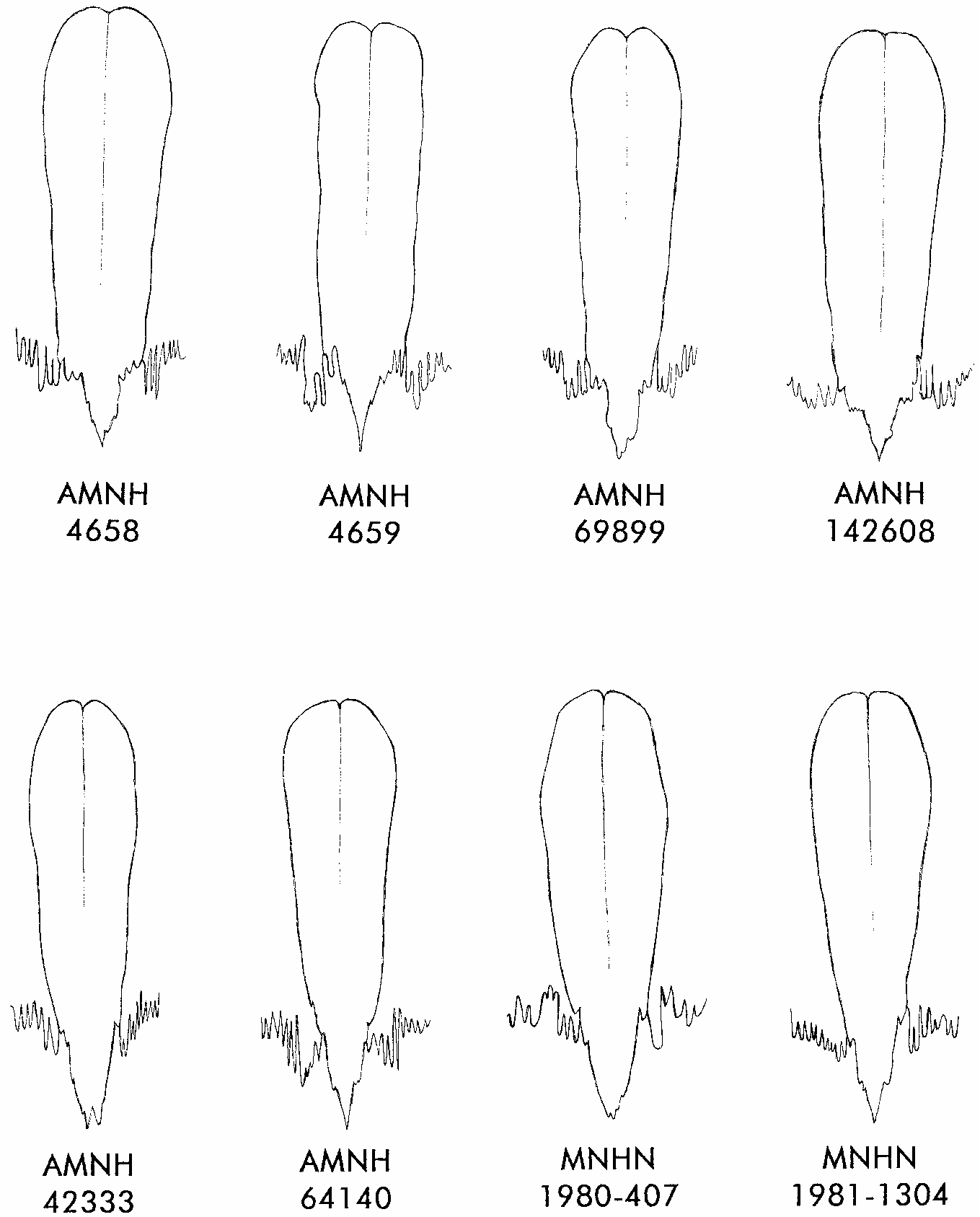

When samples of skulls are lined up in comparative series, each species has a distinctive dorsal gestalt as a consequence of taxonomic variation in four anatomically adjacent and visually juxtaposed structures: (1) The rostrum varies in absolute and relative length, being longest on average in tenuipes and shortest in paracou ; the rostrum is of intermediate length in guianae and dubosti . (2) The zygomatic notches (dorsal emarginations of the maxillary bone flanking the base of the rostrum) vary in depth as a correlate of variation in the width of the zygomatic plate; the zygomatic notches are deepest and the zygomatic plates widest in paracou , whereas tenuipes , guianae , and dubosti have shallower zygomatic notches and correspondingly narrower zygomatic plates. (3) The interorbital region is relatively narrow, and the supraorbital beads are relatively weakly developed (seldom produced as shelflike projections over the posterior orbits) in tenuipes and guianae ; in these species, the modal interobital morphology could be described as weakly convergent (fig. 38A). By contrast, dubosti and paracou have relatively broader interorbits, and the supraorbital beads are more frequently developed as projecting shelves; their modal interorbital morphology is strongly convergent (fig. 38B). (4) The braincase is relatively broader and more inflated in dubosti than in any of the other three species.

Taxonomic variation in other quantitative and qualitative cranial traits also contributes to species recognition. The incisive foramina of paracou are longer in relation to the diastema (LIF averaging about 65% of LD) than those of tenuipes , guianae , and dubosti (in which this proportion averages about 56– 57%), and subtle taxonomic differences in the shape of these diastemal perforations are also present. Thus, the foramina are relatively narrow in proportion to their length and usually have subparallel lateral margins in paracou , whereas the foramina are relatively broader with more convex or anteriorly convergent lateral margins in the other species.

Although the shape of the auditory bullae exhibits individual variation within most population samples, the bullae of paracou are more consistently globular in form, each consisting of a roughly spherical tympanic capsule that is usually abruptly constricted anteromedially to form narrow bony eustacian tubes (fig. 42B). By contrast, the bullae of tenuipes , guianae (fig. 42A), and dubosti are usually flaskshaped, each tapering gradually from the tympanic annulus to a rela tively broader eustacian tube. Insufficient in itself for species diagnosis, this character is nevertheless useful for corroborating identifications when used in conjunction with other traits.

The morphology of the first maxillary mo lar also differs significantly among the four species (fig. 43). In tenuipes , M1 is moreorless rectangular in outline because the anterocone is almost as broad as the paraconeprotocone cusppair behind it. In many specimens with unworn dentitions (especially from the central Andean cordillera of Colombia; e.g., FMNH 70126, USNM 499555), the anterocone is deeply divided into anterolingual and anterolabial conules by an anteromedian flexus, and the anteroloph is large and distinct. The occlusal organization of the tooth is strikingly symmetrical, with subequal lingual and labial cusps that remain persistently tubercular with moderate wear. The mesoloph is a slender crest of enamel, perpendicular to the long axis of the tooth, that forms a Yshaped junction with the median mure and lacks a disproportionate connection to either of the two principal lingual cusps (protocone and hypocone).

The modal morphology of M 1 in guianae and dubosti is essentially similar to that seen in tenuipes , but differs in certain details. Thus, the anterocone is undivided and usually distinctly narrower than the protoconeparacone cusppair, giving the tooth a less rectangular and more eggshaped outline, and the anteroloph is seldom distinct (the anteroflexus usually persisting, if at all, only as a small internal fossette). There is also a ten dency, that is more marked in some specimens than in others, for the labial cusps (paracone and metacone) to be reduced in size relative to their lingual counterparts (protocone and hypocone), resulting in a less symmetrical occlusal design. In addition to these shape differences, the toothrow is absolutely shorter in guianae than in either tenuipes or dubosti .

The typical morphology of M 1 in paracou differs in several respects from that seen in the other three species. The tooth is visibly narrower in relation to its length, on average, and the undivided anterocone is usually much narrower than the protoconeparacone cusppair behind it. In most specimens, this tooth exhibits a striking departure from bilateral symmetry, with the labial cusps being much reduced in size relative to their lingual counterparts, and with an enlarged mesoloph that runs obliquely and disproportionately from the hypocone to the labial cingulum. In addition, the principal cusps are not persistently tubercular because they are quickly worn down to enamel loops; thus, even moderately worn dentitions are essentially flatcrowned, lacking any significant occlusal relief.

REMARKS: Specimens that we examined and determined to be Neacomys paracou include at least some of the material previously identified as N. guianae by Anthony (1921a), Husson (1978), Guillotin (1982), Malcolm ( 1990), and Voss and Emmons (1996: appendices 4 and 5). It is probable that other literature records of N. guianae are also based partly or entirely on specimens of N. paracou , which appears to be the commonest and most widespread of the three Neacomys species now known from the Guiana subregion of Amazonia.

SPECIMENS EXAMINED: Brazil — Amapa´, Serra do Navio ( USNM 461570 About USNM , 461577 About USNM , 461578 About USNM , 461583 About USNM , 461585 About USNM , 461586 About USNM , 461596 About USNM , 461597–461600 About USNM , 461603 About USNM , 461605 About USNM , 461608 About USNM , 461609 About USNM ) ; Amazonas , 80 km N Manaus ( USNM 580008–580011 About USNM ) ; Para´, Cachoeira Porteira ( USNM 546277–546281 About USNM ). French Guiana — Arataye ( MNHN 1986.284 – 1986.286 , 1986.870 – 1986.875 ), Cacao ( MNHN 1986.536 , 1986.539 ), Cayenne ( MNHN 1983.419 , 1983.420 ), Mont St. Michel ( MNHN 1983.411 ), Paracou ( AMNH 266542 , 266544–266546 , 266548–266550 , 266552–266557 , 267570 , 267572 , 267574– 267577 ; MNHN 1995.1013 – 1995.1022 [ type series]), Saül ( MNHN 1983.405 , 1983.418 , 1983.421 , 1983.424 ), St.Eugène ( MNHN 1998.1834 , 1998.1836 – 1998.1838 ). Guyana —‘‘ River Supinaam’ ’ ( BMNH 10.5.4.22) ; Barima Waini, Baramita ( ROM 100947 About ROM ) ; Cuyuni Mazaruni, Kartabo ( AMNH 42893 , 64146 , 64147 , 142821 , 245037 ) ; Potaro Siparuni, Kurupukari in Iwokrama Reserve ( BMNH 1997.44 , 1997.46 ) ; Upper Takutu Upper Essequibo, Nappi Creek in Kanuku Mountains ( ROM 31760). Surinam — Brokopondo, 18.5 km W Afobakka ( CM 54016 ), Locksie Hattie on Saramacca River ( FMNH 95642 About FMNH , 95643 About FMNH ) ; Marowijne, Oelemarie ( CM 76838 , 76844 ), Perica ( CM 76845 ). Venezuela — Bolívar, San Ignacio Yuruaní ( AMNH 257269–257271 ) .

FIELD OBSERVATIONS: All of our inventory records of Neacomys paracou are based on collected specimens (N = 29), of which 17 (62%) were taken in Sherman traps, 8 (28%) were taken in pitfalls, 3 (10%) were taken in Victor rat traps, and 1 was shot. Most trapped specimens were found at dawn, but a single specimen was found in the late afternoon in a pitfall that had been checked earlier on the same day. Fourteen specimens (48% of the total) were shot or trapped in secondary veg etation, 10 (35%) were trapped in welldrained primary forest, and 5 (17%) were trapped in swampy primary forest. All specimens were collected at or near ground level. Of the 18 Sherman or Victortrapped specimens, most were taken in dense undergrowth near woody shelter: under logs ( 6 specimens), on top of logs (3), among stilt roots (3), beside logs (2), under piled branches (2), inside a hollow log (1), and at the base of a tree (1).

Nectomys melanius Thomas Figures 44 View Fig , 45B View Fig , 46B View Fig , 47B View Fig

VOUCHER MATERIAL: MNHN 1998.680, 1998.681. Total = 2 specimens.

IDENTIFICATION: The genus Nectomys was last revised by Hershkovitz (1944), who recognized all of the material he examined as belonging to one or the other of two polytypic species assigned to different subgenera, Nectomys ( Nectomys) squamipes (Brants) and N. ( Sigmodontomys) alfari (J. A. Allen) . Current usage (summarized by Musser and Carleton, 1993), however, recognizes Sigmodontomys and Nectomys as full genera, the former with two valid species ( S. alfari and S. aphrastus ) and the latter with three ( N. palmipes , N. parvipes , and N. squamipes ). Only Nectomys (sensu stricto) is known to occur in Amazonia, Sigmodontomys being restricted to transAndean and Venezuelan coastal rainforests (Voss and Emmons, 1996: table 1).

Nectomys squamipes melanius was originally described by Thomas (1910: 185–186), who considered it ‘‘the Guianan representative of the Brazilian water rat, N. squamipes View in CoL , but... distinguishable by its darker dorsal color and smaller skull and teeth.’’ Thomas’s account was based on a small series of specimens from Guyana and Surinam, but additional material identified as melanius was subsequently described by Hershkovitz (1944) and Husson (1978). Whereas both Hershkovitz and Husson followed Thomas in treating melanius as a valid subspecies of N. squamipes (Brants, 1827) View in CoL , Tate (1939) synonymized melanius with N. s. palmipes View in CoL , a taxon that was originally described (as a full species) by Allen and Chapman (1893) from Trinidad. Petter ( 1979) subsequently de scribed N. parvipes View in CoL from French Guiana and compared it with sympatrically collected material that he identified as N. s. melanius . The identification of our voucher material therefore involves each of the three species of Nectomys View in CoL regarded as valid by Musser and Carleton ( 1993).

All of the French Guianan material we examined agrees closely with the descriptions of Nectomys squamipes melanius provided by Thomas (1910), Hershkovitz (1944), and Husson (1978). The French Guianan holotype of Nectomys parvipes , raised in the laboratory from a wildcaught nestling (Petter, 1979), appears to be no more than an unusually small individual (table 23), perhaps stunted by an inadequate diet or other captive conditions. We examined this specimen ( MNHN 1979.345) and determined that none of its qualitative characters diverge from the range of variation exhibited by other specimens of French Guianan Nectomys with substantially larger measurements. Although the range of variation in molar length (LM) in our French Guianan series is considerable ( 5.9–7.1 mm), there is no hint of bimodality in the frequency distribution of this measurement, and there is no correlated variability in other characters to suggest that our sample is composite. French Guianan skins are not quite as dark, on average, as topotypical melanius from Guyana, but this appears to be the only point of external difference. Although measurements of Guyanese exemplars suggest that there may be a modest easttowest increase in average molar size in this taxon (table 23), our sidebyside comparisons of French Guianan and Guyanese specimens revealed no qualitative craniodental differences. Based on specimens we examined, the same phenotype apparently extends westward into the Venezuelan state of Amazonas, and southward into the Brazilian state of Pará on the north bank of the Amazon.

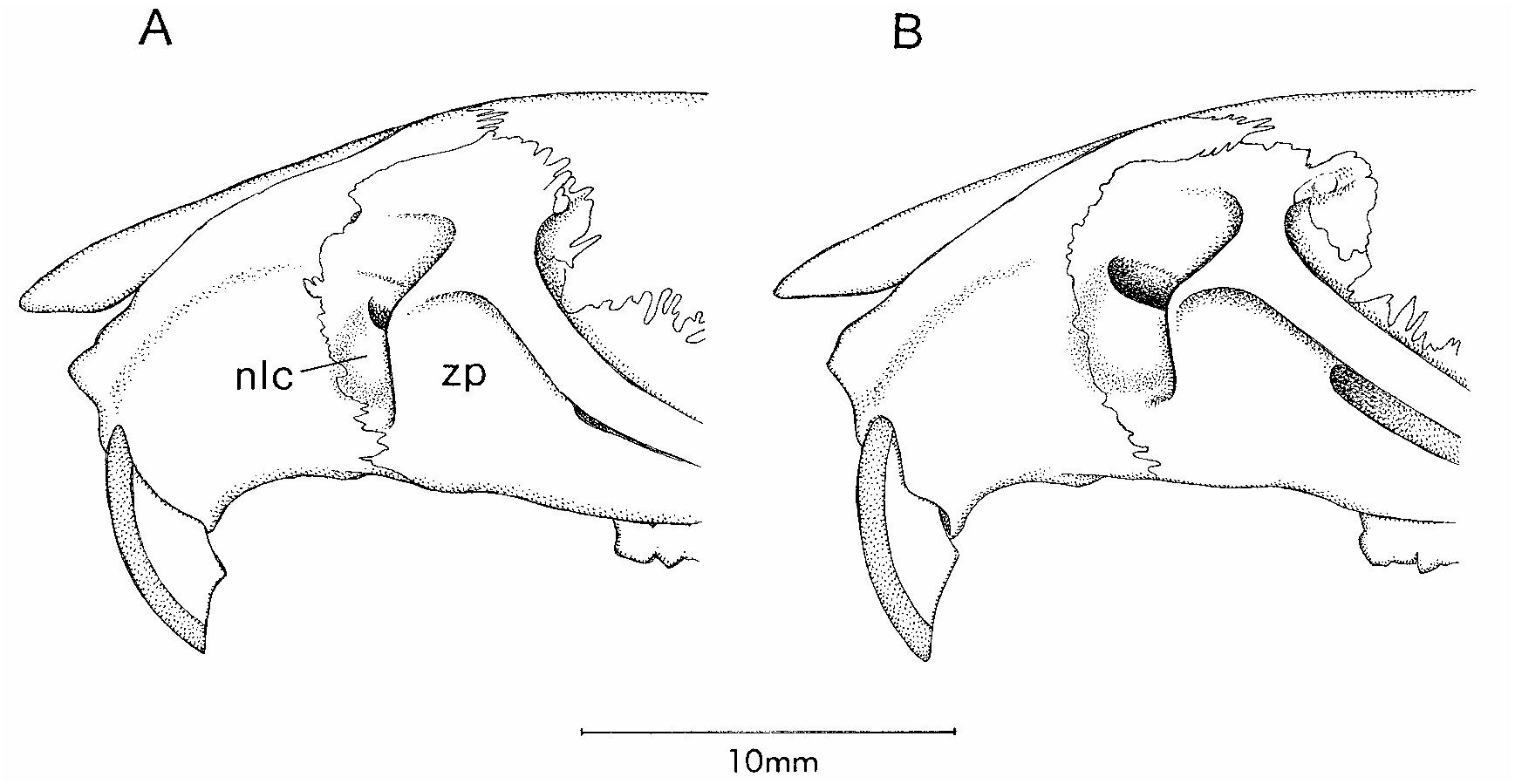

We provisionally recognize Nectomys melanius as a distinct species based on geographical, morphological, and cytogenetic comparisons with both of the taxa that have previously been considered to be senior synonyms (table 24). From N. palmipes , its nearest neighbor, melanius differs conspicuously in diploid chromosome counts (2N = 16–17 versus 2N = 52–56; references in footnotes to table 24) and in several morphological traits that can be used to identify museum specimens unaccompanied by karyotypes. (1) Whereas the lateral margins of the nasal bones taper gradually from front to back in melanius without a sharp change in angle at the premaxillaryfrontal suture, the nasals of palmipes are more abruptly constricted behind the premaxillae (fig. 44) in most of the specimens we examined. 12 (2) The interparietal bone is a shallow and wide element in melanius (fig. 45B) versus deeper and narrower in palmipes (fig. 45A), a difference that is correlated with a marked dorsolateral expansion of the exoccipital in the latter species. (3) The nasolacrimal capsules on the sides of the rostrum are mostly exposed to lateral view in melanius (fig. 46B), but these structures are partially concealed by the zygomatic plate in palmipes (fig. 46A). (4) The tegmen tympani is usually inconspicuous in melanius (fig. 47B), but a large anterior process of the tegmen tympani is always present in palmipes (fig. 47A).

Based on museum specimens that we sort ed by these four morphological characters, Nectomys palmipes occurs throughout the island of Trinidad, where the type ( AMNH 5928/4658) was collected at Princestown. This species also occurs on the adjacent Venezuelan mainland, from which we examined several specimens including the type of Nectomys squamipes tatei Hershkovitz (1948a) . Collected at San Antonio in the Venezuelan

12 In addition to the Trinidadian specimens listed in table 23 (footnote e), we examined AMNH 69899 (the holotype of tatei), AMNH 142608, and USNM 415009 from northeastern Venezuela.

TABLE 23 Measurements (mm) and Weights (g) of Nectomys melanius and N. palmipes

state of Monagas, the type of tatei ( AMNH 69899) is craniodentally indistinguishable from Trinidadian material, as are two additional specimens from Monagas ( AMNH 142608, USNM 415009); all were collected within the mapped distribution of karyotyped individuals with 2N = 16–17 chromosomes (in the states of Anzoategui, Delta Amacuro, Monagas, and Sucre; Barros et al., 1992). However, a single specimen with the same morphological characters ( AMNH 16964) is from El Llagual (ca. 7°25̍N, 65°10̍W) in the northern part of Bolívar state. Because material from southern Bolívar (e.g., AMNH 75634, 75635, 130733, 130784) is unambiguously referable to melanius , specimens of water rats from intermediate localities in that state should be examined carefully to determine whether melanius and palmipes (the latter including tatei as a subjective junior synonym) are parapatrically or sympatrically distributed in eastern Venezuela.

Nectomys melanius closely resembles N. squamipes in all of the morphological traits by which N. palmipes differs from both (table 24), but we are persuaded by the karyotypic data and breeding experiments reported by Bonvincino et al. (1996), which suggest that the water rats of southeastern Brazil represent a distinct species from Amazonian populations. Based on the restricted type locality of squamipes (São Sebastião, São Paulo state; see Hershkovitz, 1944), this would appear to be the correct name for Bonvincino et al.’s southeastern Brazilian taxon. We agree with Patton et al. (2000) that aquaticus Lund ( type locality: near Lagoa Santa, Minas Gerais) and olivaceus Hershkovitz ( type locality: Therezopolis, Rio de Janeiro) are probable synonyms of N. squamipes , and that this species probably extends into northern Argentina. The observations of Peters (1861) and Hershkovitz (1944), together with our own examination of southeastern Brazilian

TABLE 24 Geographic, Morphological, and Karyotypic Comparisons among Three Species of Nectomys

material suggest that the hindfeet of N. squamipes usually have six plantar tubercles, whereas the hindfeet of most specimens of N. melanius lack a distinct hypothenar (lateral tarsal) pad.

Patton et al. (2000) used the name apicalis Peters (1861) for western Amazonian populations of Nectomys with low diploid numbers (2N = 38–42 chromosomes), large teeth (LM = 7.0– 7.4 mm), and deepnarrow interparietals. 13 Based on the difference in diploid numbers alone, it seems unlikely that apicalis and melanius intergrade in western Amazonia (contra Hershkovitz, 1944: 51– 52), but without having seen the type of apicalis and without undertaking an extensive analysis of morphological variation in west

13 Barros et al. (1992) previously used the junior name garleppi Thomas (1899) for this form, and it is possible that other nominal taxa may also be synonyms.

ern Amazonian populations of Nectomys , we are unable to rule out this possibility.

REMARKS: It seems probable that Nectomys rattus , originally described by Pelzeln (1883) based on a single immature specimen collected at Marabitanas (0°58̍N, 66°51̍W) on the upper Rio Negro in the Brazilian state of Amazonas, is a senior synonym of melanius . Although we have not seen Pelzeln’s problematic type, 14 the geographic proximity of

14 Thomas (1897: 497) remarked that the immature type of Hesperomys rattus Pelzeln ‘‘is clearly a Nectomys ’’, but he did not explicitly state that he had seen the specimen. Tate (1939) apparently accepted Thomas’s assignment of rattus to Nectomys , but Hershkovitz (1944: 30) objected on the grounds that Pelzeln’s original description was not informative about generic characters: ‘‘Until the type itself, if still extant, can be examined, Hesperomys rattus , if at all identifiable, cannot be identified as a Nectomys . ’’ Although we have not seen the type, we did consult Thomas’s manuscript notes (in the library of the Natural History Museum, London), which

Marabitanas to Venezuelan localities from which we have examined specimens referable to melanius tends to support this synonymy. Clearly, a comprehensive revision of Nectomys based on firsthand examination of relevant types and a critical analysis of morphological variation among the many hundreds of museum specimens now available for study will be essential for resolving this and other taxonomic enigmas. In the meantime, N. melanius is the oldest available name that we can confidently apply to the material at hand.

OTHER SPECIMENS EXAMINED: Brazil — Para´, Cachoeira Porteira ( USNM 546290 About USNM , 546291 About USNM ). French Guiana —Arataye ( MNHN 1981.162 ), Awara ( MNHN 1986.271 ), Cacao ( MNHN 1979.345 [ holotype of parvipes ], 1981.1303, 1981.1304, 1986.272, 1986.273), Cayenne ( MNHN 1970.224 , 1981.1298 , 1981.1299 , 1986.274 , 1986.275 ), Rorota ( MNHN 1981.1305 ), Ouanary ( MNHN 1981.1297 ), Piste St.Élie ( MNHN 1981.184 ), Saül ( MNHN 1980.407 , 1981.1296 , 1986.270 ) . Guyana — Cuyuni Mazaruni, Kartabo ( AMNH 42332 , 42333 , 42882 , 42885 , 42891 , 64140 ), Oko Mountains ( USNM 46216 About USNM ) ; Upper Demerara Berbice, Rockstone ( AMNH 34651 ) . Venezuela — Amazonas, Acanaña ( USNM 406237 About USNM ), Boca Mavaca ( USNM 374662 About USNM , 374664 About USNM , 374665 About USNM , 406062 About USNM , 406063 About USNM , 406233 About USNM ), Cerro Neblina Base Camp ( USNM 560824 About USNM ), Esmeralda ( AMNH 77303 ), Mt. Duida ( AMNH 77306 ), Río Casiquiare ( AMNH 78080 ), San Carlos de Río Negro ( USNM 560650 About USNM ) ; Bolívar, Auyantepui ( AMNH 130733 , 130784 ), Mt. Roraima ( AMNH 75634 , 75635 ) .

FIELD OBSERVATIONS: Both of our vouchers of Nectomys melanius were collected by O. Henry, whose field notes indicate that one was trapped ‘‘près de la crique’’ on 4 November 1989, and the other ‘‘sur la piste’’ on 20 April 1990.

include a bound volume of observations about the specimens he examined in European museums. Page 73 records his description of Pelzeln’s type of Hesperomys rattus (in the NMW) as ‘‘a young... Nectomys ... the toe webbing quite visible’’. Unfortunately, no other diagnostic characters were given, and we are not aware that anyone else has subsequently examined this specimen.

Neusticomys oyapocki (Dubost and Petter) Figures 48 View Fig , 49B, 49D View Fig

VOUCHER MATERIAL: AMNH 267597 ; MNHN 1995.992 . Total = 2 specimens .

IDENTIFICATION: Our two vouchers and another specimen subsequently collected at nearby St.Eugène provide an opportunity to reevaluate the characters of this obscure taxon. Previously known from a single specimen (MNHN 1977.775) from Trois Sauts in southeastern French Guiana, Daptomys oyapocki was initially diagnosed only by the absence of upper and lower third molars, and by the small size of its remaining cheekteeth (Dubost and Petter, 1978). Other distinctive attributes of the holotype were reported by Voss (1988), who treated Daptomys as a junior synonym of Neusticomys . The new material closely resembles the type and corroborates the status of N. oyapocki as a valid species.

The Paracou examples are both males. The smaller specimen (MNHN 1995.992) we judge to be subadult because of its uniformly blackish pelage, undescended testes, conspicuous metapodial epiphyses, and open basicranial sutures; although its molar dentition (see below) is completely erupted, the animal is obviously immature. The larger specimen (AMNH 267597; figs. 48, 49B, 49D) appears to be a young adult; its pelage is also dark, but the color is distinctly brownish and finely ticked with tawnybanded hairs, the testes are scrotal, the metapodial epiphyses are inconspicuous (but perhaps not completely absorbed), and the basicranial sutures are closed (although not completely fused). In fact, AMNH 267597 seems to be nearly the same age as the holotype and compares with it closely in external and cranial dimensions (table 25). The specimen from St.Eugène is a fully adult male, with fur like the larger Paracou specimen, wellworn molars, and fused basicranial sutures.

Like the holotype, all of the three new specimens of Neusticomys oyapocki lack M3/ m3, and the remaining molars are small by comparison with their homologs in the only other Guianan congener, N. venezuelae (fig. 49). As noted by Voss (1988), loss of the third molar is accompanied by morphological changes in the second, now the most poste rior element in the toothrow. In all specimens of N. oyapocki , the hypocone/metacone lobe of M2 is greatly reduced by comparison with that of N. venezuelae , and there is no trace of a posteroloph.

Neusticomys oyapocki can be distinguished from other lowland congeners (formerly classified as Daptomys ; fig. 50) by additional characters: (1) The ears and feet of N. mussoi and N. peruviensis are creamcolored and contrast with the brownish dorsal body pelage, but the ears and feet of N. oyapocki and N. venezuelae are dark brown and do not contrast with the dorsal fur. (2) In N. venezuelae and N. mussoi , the posterior edge of the inferior zygomatic root (zygomatic plate) lies above or just anterior to the anterocone of M1; in fully adult examples of N. oyapocki and N. peruviensis , however, the posterior edge of the inferior zygomatic root is located well anterior to the toothrow (fig. 48; also see illustrations in Musser and Gardner [1974], Voss [1988], and Ochoa and So riano [1991]). (3) A small orbicular apophysis of the malleus is present on the type (and only known fully adult specimen) of N. peruviensis , but this structure is absent in both N. oyapocki and N. venezuelae ; the character has not been described or illustrated for N. mussoi . Table 26 summarizes these and other relevant comparisons.

Two peculiarities of the holotype of Neusticomys oyapocki noted by Voss (1988) are apparently not diagnostic for the species. The type lacks masseteric tubercles, the bony processes from which M. masseter superficialis originates in ichthyomyines, but a distinct masseteric tubercle is present at the base of the inferior zygomatic root on each side of the skull in the larger Paracou specimen (AMNH 267597) and in MNHN 1995.3234 (from St.Eugène). The type of N. oyapocki also appears to have an unusually narrow interorbital constriction by comparison with both of the other conspecific adults at hand,

TABLE 25 Measurements (mm) and Weights (g) of Neusticomys oyapocki and N. venezuelae

and with specimens of N. venezuelae (table 25).

OTHER SPECIMENS EXAMINED: French Guiana —St.Eugène (MNHN 1995.3234), Trois Sauts (MNHN 1977.775 [ holotype]).

FIELD OBSERVATIONS: Both of our specimens of Neusticomys oyapocki from Paracou were taken in pitfall traplines in primary forest. The first example (AMNH 267597) was collected on 14 August 1993 about 5 m from a small (ca. 1.4 m wide), shallow (ca. 20 cm deep), clear, sandybottomed stream; the habitat at this site is perhaps best characterized as moist creekside forest on level sandy soil (fig. 51). The second animal (MNHN 1995.992) was taken on 8 September 1993 at approximately the same distance from a slightly smaller stream, but on sloping, welldrained ground. The remains of small crabs (fig. 52) found along other streams in our study area suggest that this species is not uncommon locally, but intensive trapping with Victors and Tomahawks set at streamside and baited with crabs produced no additional specimens.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.