Rana temporaria Linneaus 1758

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5301.3.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A64620A-5346-459A-9330-7E8AE9EBEBDE |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8040601 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03BE87CB-FF86-4A6E-B888-7B74410BF838 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Rana temporaria Linneaus 1758 |

| status |

|

Common Frog Rana temporaria Linneaus 1758 View in CoL View at ENA

Distribution ( Figure 5 View FIGURE 5 ). Included records from Artportalen (N=2000): a ubiquitous species for which all reported records have been included.Any rare confusion with Rana arvalis would not change the overall picture of distribution or abundance.

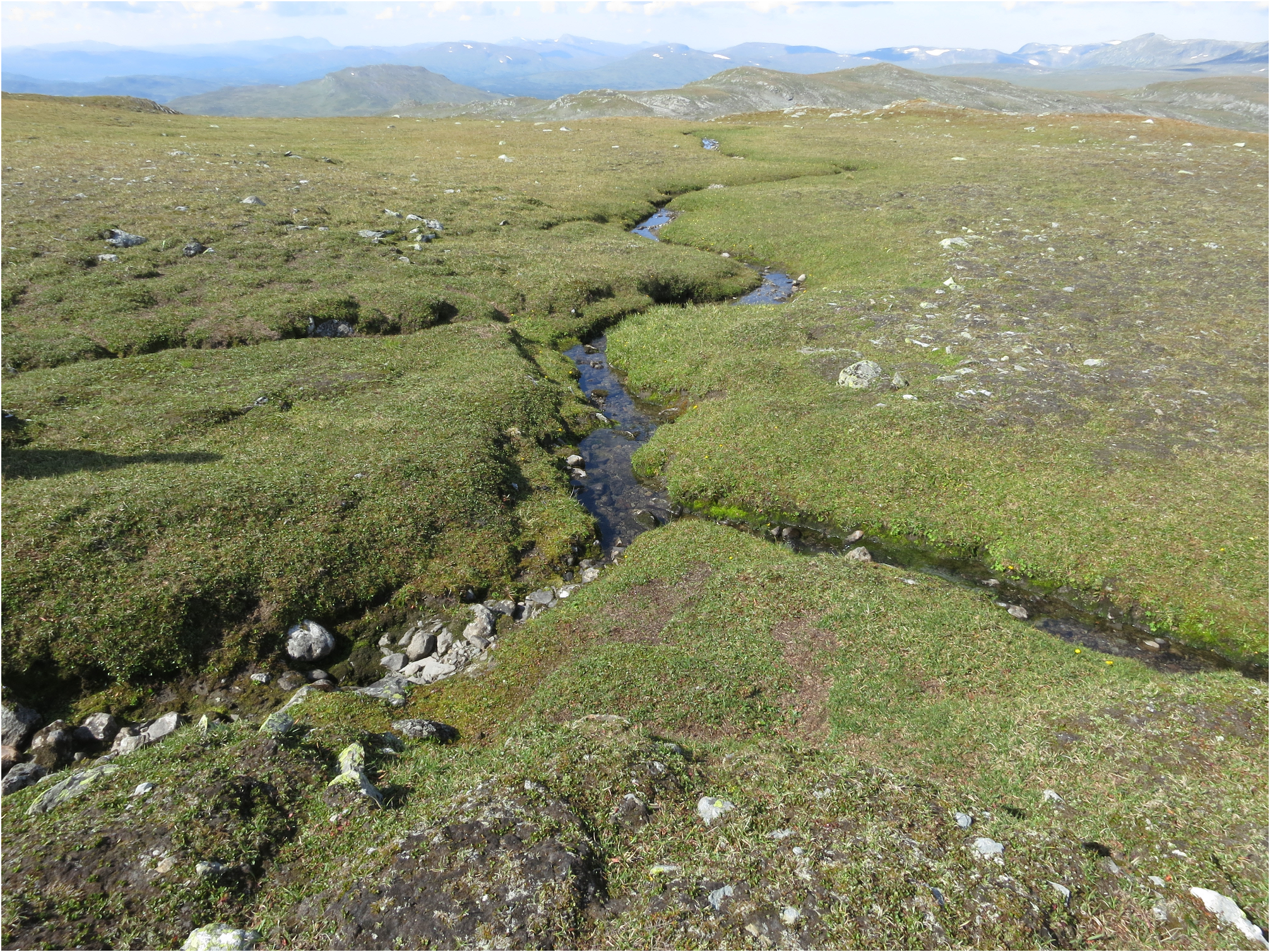

Widespread and abundant throughout the Southern Boreal, Middle Boreal, Northern Boreal regions, and in the Subalpine life zone. Widespread and locally common in the Low-Alpine zone. Scattered occurrences in the Mid-Alpine zone ( Figures 15 View FIGURE 15 , 16 View FIGURE 16 ).

Breeding sites in the Low-Alpine zone reach at least 840 m altitude in Lycksele lappmark ( Elmberg 1991; Figure 17 View FIGURE 17 ) and probably up to or above 1000 m further south in the Scandic Mountains. In other words, it is a widespread breeder well above treeline. In summertime adults have been observed at 1070 m in Åsele lappmark and Lycksele lappmark, and at up to 1400 m in Jämtland (Helagsfjället), all of which are in the upper part of the Mid-Alpine zone.

Occurrence and reproduction are known from several far offshore islands in the Baltic in the three northernmost coastal provinces ( Norrbotten, Västerbotten, and Ångermanland), where distributed offshore equally widely as Bufo bufo . In the coastal provinces farther south, however, offshore occurrence is scarcer and concentrated to more nearshore islands. This may indicate a somewhat lower dispersal capacity over brackish water than in Bufo bufo .

There are no signs of changes in distribution during the last 50 years.

Habitat and movements. Spring migration of adult males to breeding ponds is largely nocturnal and often strongly synchronized, with up to 50% arriving within a few days ( Elmberg 1990). Adult females arrive more gradually to breeding sites ( Elmberg 1990). Juveniles emerge later than adults and are rarely seen before the spawning period is over.

Breeding habitats range from ponds and bogs above treeline ( Figure 17 View FIGURE 17 ), through any type of wetland and lake in lower biotic regions, to sheltered shallow brackish bays of the Baltic ( Elmberg et al. 1979). They further range from wetlands in pristine forest to landfill swamps, flooded disused gravel pits and quarries, and man-made ponds in residential areas. The entire range from the most oligotrophic to the most eutrophic conditions is utilized for breeding ( Figures 11 View FIGURE 11 , 14 View FIGURE 14 ). This is the most frequently encountered anuran breeding in barren rock pools along the Baltic seashore ( Figure 12 View FIGURE 12 ). Calling males and spawn clumps are usually found in shallow and well vegetated situations, that is, less exposed than eggs of Bufo bufo and Rana arvalis . Females remain in breeding wetlands only until they have deposited their eggs, whereas adult males remain as long as there are receptive females around, or longer ( Elmberg 1990).

Dispersal from breeding sites to nearby summer foraging habitats is gradual and not very conspicuous. Since Rana temporaria is so widespread and abundant, summer foraging habitats are extremely diverse, from alpine heath, open coniferous forest to dense bottomland woods along the major rivers ( Figures 15 View FIGURE 15 , 18 View FIGURE 18 ). The highest summer densities are observed in abandoned fields and grassy meadows along lakes, rivers, and seashore, but also in deciduous forests with well-developed undergrowth ( Figure 13 View FIGURE 13 ). Close to nothing is known about movements and home range in summer. Autumn migration to hibernation sites is usually conspicuous and synchronized, triggered by rains or mild cloudy conditions.

Hibernation in North Sweden is aquatic. It may take place in breeding wetlands if not prone to developing anoxic conditions in winter. However, in most cases Rana temporaria migrate to spend the winter in nearby welloxygenated streams and rivers. There they seek shelter on the bottom in nearshore aquatic vegetation, but they will move to deeper water later in winter if the ice sheet expands downwards or if the water level recedes. Hibernation has also been observed in springs and natural wells in closed forest, as well as in brackish water in the Baltic ( Elmberg et al. 1979). Terrestrial hibernation in the boreal is known from Norway ( Frislid & Semb-Johansson 1981) and Finland ( Pasanen & Sorjonen 1994) and may occur in North Sweden, although it has not been documented. Experimental work in Finland strongly indicates that the species cannot survive more than a few days of freezing temperatures at the most ( Pasanen & Karhapää 1997), making it a much less likely terrestrial hibernator than Rana arvalis .

Abundance estimates and trends. Throughout the 1980’s I studied two populations in Umeå, Västerbotten, at breeding sites encircled by built-up urban areas (Tvärån: 63°49’50.9”N, 20°13’38.4”E and Bölesholmarna: 63°49’31.4”N, 20°14’6.7”E). The GoogleMaps summer foraging habitat surrounding these ponds comprises mid- to late successional riparian deciduous woodland (2.5 and 15 hectares, respectively; Figure 18 View FIGURE 18 ). Counts GoogleMaps of calling males at both sites and drift fence catch data from the Tvärån GoogleMaps site permitted accurate estimates of population size ( Elmberg 1990). Accordingly GoogleMaps , the density of adult frogs in these summer habitats averaged 65–75/hectare (i.e., 6500–7500/ km 2). In GoogleMaps the 1990’s the isolated and far offshore island Stora Fjäderägg GoogleMaps in Västerbotten ( 63 o 48’N 21 o 00’E; area ca 170 hectares) was subject to a census of spawn clumps in all its wetlands (Stefan Andersson, personal communication). Supposing GoogleMaps an even sex ratio and that each female laid one egg clump, the island’s population was 1200 adults (both sexes), that is, 7/hectare (700/km 2). The density of adults in summer habitat on Low-Alpine heath well above treeline (Kraipe, Lycksele lappmark; 65°50’4.0”N, 16°22’23.0”E; altitude 780 m; Figure 17 View FIGURE 17 ) was estimated at 2–4/ hectare (200–400/km 2) in a population studied by me for several years in the late 1980’s.

The abundance estimates from the two Umeå sites are remarkably similar and probably close to the maximum occurring in North Sweden. Stora Fjäderägg and Kraipe, on the other hand, both represent suboptimal habitats. I propose that an abundance of 600 adults /km 2 is a realistic average value for North Sweden, from the Southern Boreal up to and including the Subalpine zone.

There are no indications of changes in abundance during the last 50 years.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.