Acanthocercus atricollis ( Smith, 1849: 14 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00222933.2018.1435833 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03BFD058-FF8F-FFB2-14DC-8B49BD22FF57 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Acanthocercus atricollis ( Smith, 1849: 14 ) |

| status |

|

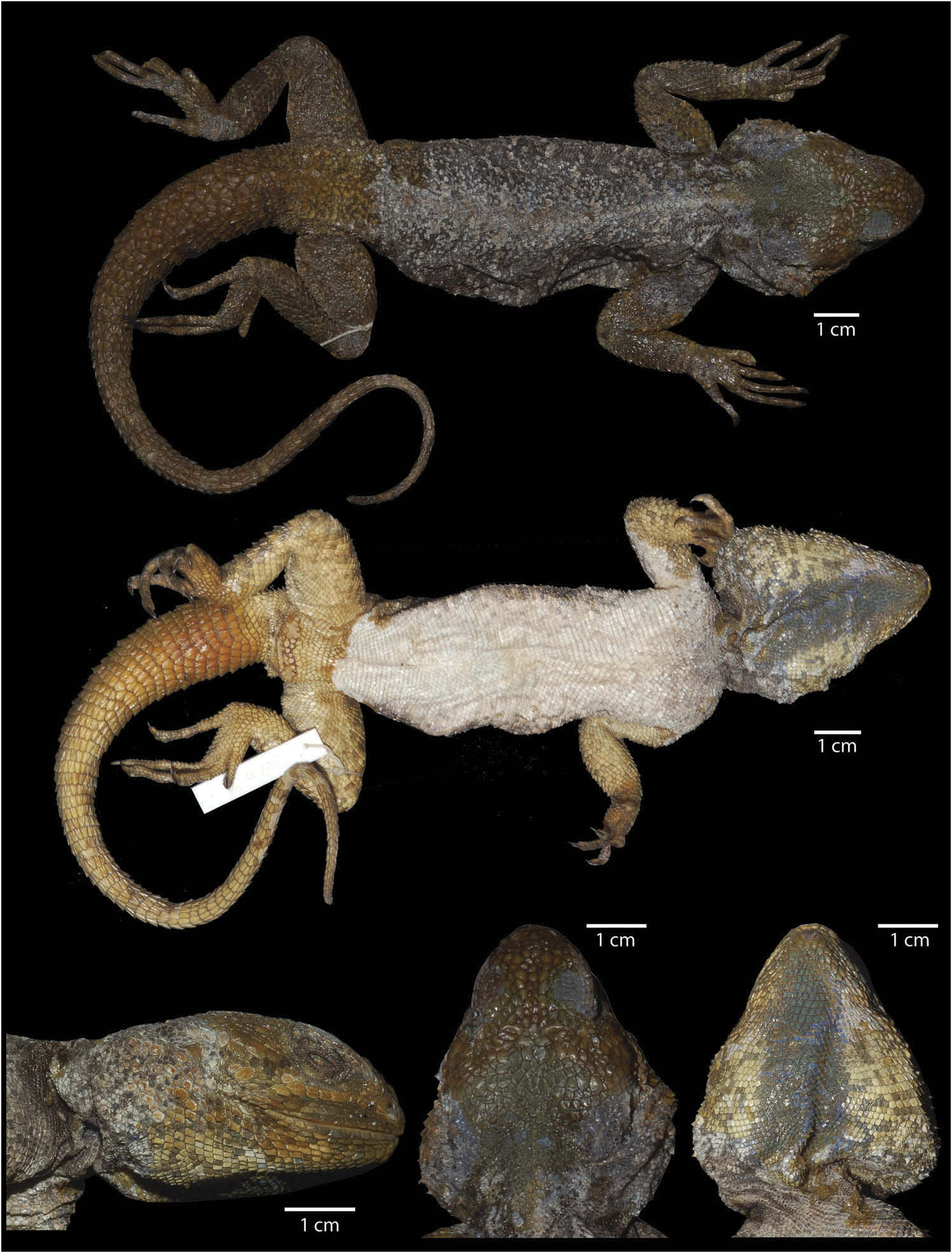

Acanthocercus atricollis ( Smith, 1849: 14)

( Figure 9 View Figure 9 )

1849 Agama atricollis Smith, Illustrations of the Zoology of South Africa. 3 (Reptiles, Appendix). Smith, Elder and Co., London: 14.

1851 Stellio capensis A. Duméril in Duméril & Duméril, Catalogue méthodique de la collection des reptiles du Muséum d’ Histoire Naturelle. Paris: 106. Type locality: ‘ Cap de Bonne-Espérance’ [= Cape of Good Hope], South Africa (fide Wermuth 1967) .

1866 Agama nigricollis Barboza du Bocage (lapsus calami), Lista dos reptis das possessoes portuguezas d’ Africa occidental que existem no Museu de Lisboa. Jornal de sciencias mathematicas, physicas, e naturaes, Lisboa 1: 43.

Lectotype

BMNH 1946.8 .28.1 (formerly 1865.5.4.5), from ‘ Port Natal’ [=Durban], South Africa, designated by Klausewitz (1957).

Taxonomic comments

Denzer et al. (1997) mentioned ZMB 16906 as the syntype of A. a. atricollis , and argued that (a) the specimen is topotypical material from the original type series and (b) no lectotype was designated before. First of all, Klausewitz (1957) designated the namebearing lectotype (BMNH 1946.8.28.1), and therefore the ZMB specimen could only be a paralectotype, not a syntype. Second, the mentioned locality ‘Rutenganio’ [museum label] obviously refers to a mission station of the ‘Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine’ founded 1891 in Tanzania (‘Deutsch-Ostafrika’ at this time and therefore with a close relationship to the Berlin Museum). The station was situated in the Rungwe area in southern Tanzania, directly north of Lake Malawi (see no. 87 in Figure 14 View Figure 14 ) and was often only referred to as ‘Herrnhut, Nyasa’. Moreover, the presumed collector Adolf Ferdinand Stolz (1871–1917), a mission trader of the ‘Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine’ and famous collector of plants and animals ( Harms 1918a, 1918b), was born decades after the description of A. a. atricollis by Smith (1849). Therefore, ZMB 16906 represents neither a former syntype nor a topotype of A. atricollis . However, this specimen still has type status as Klausewitz (1957, p. 163) included it in the paratype series of A. loveridgei .

Many authors (e.g. Loveridge 1957; Wermuth 1967) have recognized Bocage (1866) as the author of ‘ Stellio nigricollis ’ but regarded the taxon as a synonym of A. atricollis . However, in his checklist of specimens collected in western Africa and present in the Lisbon collection, Bocage (1866) mentioned the name, but referred to an ‘ Agama nigricollis ’ described by Smith with a type present in the British Museum. Furthermore, he mentioned that he previously thought that these specimens from Angola represented a new species which he meant to name ‘ St. angolensis ’, but Albert Günther (curator at the British Museum at this time), after an examination of these specimens, suggested them as conspecific with Smith’ s ‘ nigricollis ’. For that reason, Bocage declined to describe this form. Though it is mentioned in Bocage (1866), the type specimen of ‘ Agama nigricollis Smith’ is not present in the collection of the British Museum (C. McCarthy, pers. comm.) and the taxon is neither mentioned by Smith (1849) in the supposed publication of the description, nor by Boulenger (1885) in his catalogue of the specimens in the British Museum. Therefore, it is likely that (a) Bocage misread the letter he got from Günther, as Günther probably wrote atricollis rather than nigricollis ; or (b) Günther intended to write atricollis and instead wrote nigricollis by mistake. This second theory might fit as atricollis is in fact described by Smith (1849) from southern Africa, with the types present in the British Museum, and also the first syllable of both species names, ‘ atri ’ (Latin from ater) and ‘ nigri ’ (Latin from niger), mean black. Bocage (1895) also recognized this mistake and stated St. nigricollis as ‘lapsu’, without mentioning reasons. On this basis, we also recognize ‘ St. nigricollis ’ as a lapsus calami.

Denzer et al. (1997) mentioned ‘ Agama (Stellio) Antinorii ’ as a name proposed by Peters & Doria in an unpublished type catalogue of the ZMB collection. However, the name was never published.

Description

A large species with a total length up to 340 mm (SVL: 110–151 mm, x = 128.8 mm, n = 12), with the tail comparatively short, only one fourth to one third longer than the SVL. Head broad (particularly in males) and lacking the occipital scale. Nasal scale weakly convex, smooth, situated slightly below the canthus rostralis. Ear openings larger than eyes, tympanum conspicuously exposed. Nuchal crest or tufts of elongated scales absent. Body scales heterogeneous; dorsal matrix scales small, smooth and mucronate; irregularly intermixed with enlarged rhomboidal, mucronate and keeled scales. Vertebral scales larger than those on the flanks, very heterogeneous, larger scales strongly keeled, others smooth to weakly keeled. Body scales in 99–131 scale rows around midbody (x = 112.6, n = 12) and 52–74 (x = 50.5, n = 12) along the vertebrate. Gular scales smooth, slightly exposed. Ventral scales small and smooth, larger than the dorsal matrix scales in 76–94 (x = 83.2, n = 12) rows. Males with usually two continuous rows (2–3, x = 2.3, n = 12) with a total number of precloacal pores ranging between 10–12 (data from literature) or 15–34 (own data; x = 21.8, n = 12); absent in females. Scales on the upper surface of the basal part of the tail enlarged, thick and swollen, forming a distinct patch.

In males head, forelimbs and first half of the body blue; second half of the body and hind limbs reddish to yellow. Tail bicoloured, yellow in the proximal half, blue in the distal. Body coloration with a pale vertebral stripe and pale enlarged scales in the blue part, and yellow coloured enlarged scales in the reddish part. Throat of adult males pale to brilliant blue with a dark blue reticulated pattern. Females inconspicuous brownish with small black dots and fine lines. Males, females and even juveniles have a black spot at the shoulders. According to Klausewitz (1957) the body of adult males is dull blue to bluish, with yellow spiny scales, and a yellowish vertebral stripe, whereas Smith (1849) described the colour of the upper head and tail as greenish brown, or yellowish brown, the latter with narrow liver-brown rings. The latter author also mentioned a large black mark on the shoulders and described the upper and lateral parts of the body as intermediate between oil-green and yellowish brown and the throat greenish blue or straw yellow. Gough (1909) mentioned that males, when excited, have bright blue or green heads and ventral surfaces, while females and juveniles do not appear to show the green or blue tints to the same extent.

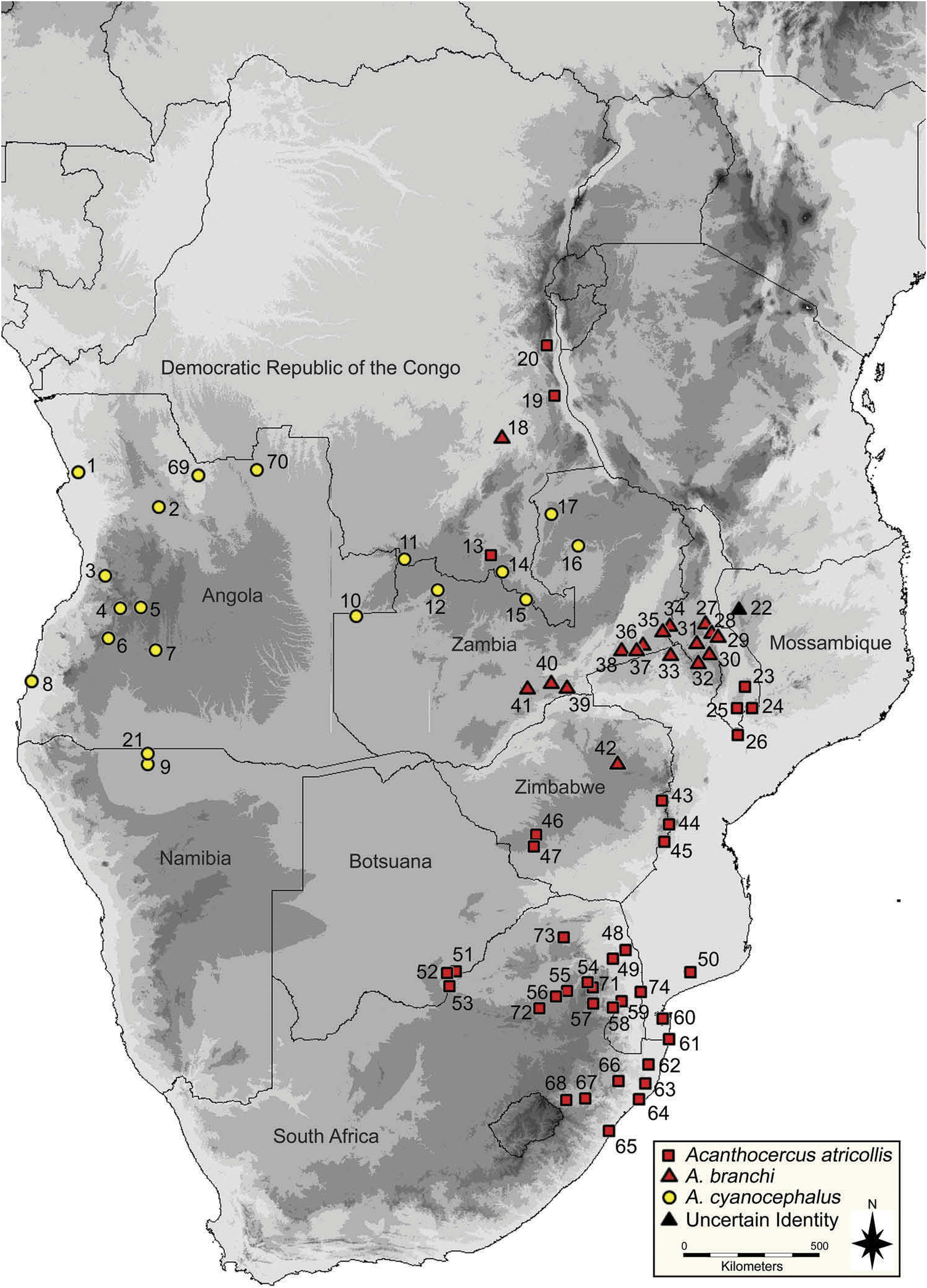

Distribution

Acanthocercus atricollis is restricted to south-eastern Africa. There are confirmed records from South Africa, Swaziland, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Malawi and Mozambique (see Figure 10 View Figure 10 ). Specimens previously recognized as A. atricollis from Namibia and Angola are now referred to A. cyanocephalus (see below). The detailed borders of the species’ distribution remain unknown. Both Klausewitz (1957) and this study recognize A. atricollis -like specimens from south-eastern DRC, which is outside the main distributional range.

Habitat

Acanthocercus atricollis is an arboreal lizard. Gough (1909) mentioned that he found the lizards invariably upon trees and that it seems that they take to the ground very unwillingly. According to Reaney and Whiting (2003) it lives in open savannah habitat and prefers thorn trees (46% Vachellia karroo ), followed by sugarbush ( Protea caffra ) and unspecified dead trees. Their analysis shows that A. atricollis prefer trees with greater diameter, canopy cover, incidence of parasitic plants and presence of holes. However, according to the same authors, the last character could be an artefact as there was no significant evidence that the lizard uses holes as refuges or retreat sites. There are no differences in habitat use between the sexes or age classes ( Reaney and Whiting 2003).

Ecology

A. atricollis is ecologically the best known species of the complex. It lives in structured colonies of one dominant male and several females ( Reaney and Whiting 2002), but often only few specimens are observed, giving the impression that only a single male with a single female live together, as mentioned e.g. by Gough (1909). Subordinate males are pushed completely out of the male’ s territory and have to establish their own outside the range of the dominant male (pers. comm. W.B. Branch). Reaney and Whiting (2002) found no differences in diet or foraging behaviour between the sexes. The diet mainly consists of ants and beetles, but grasshoppers also comprise a high proportion of their diet by volume ( Reaney and Whiting 2002). Although generally known as diurnal, A. atricollis has also been mentioned as exhibiting some nocturnal activity by Reaney and Whiting (2003) and perches at greater heights at night than in the daytime. Both females and males were observed sleeping exposed on branches, but often under foliage ( Reaney and Whiting 2003). In contrast, Branch (1998) mentioned hollow branches or holes as retreat sites. When chased the lizards slip over to the far side of the branch or to the other side of the trunk of the tree and when captured, they readily offer fight ( Gough 1909). Smart et al. (2005) recorded higher densities of A. atricollis in degraded areas than in a nearby conserved area, but found that local residents had a negative perception of tree agamas. However, Whiting et al. (2009) identified A. atricollis as anthropophilic species. Even though they are killed by local residents (some indigenous people believe them to be poisonous, see Gough 1909), the population density in villages was higher than in adjacent disturbed communal rangelands or a nearby undisturbed protected area. The authors suggested three major contributing factors: 1 = Dande; 2 = Malange; 3 = Mombolo; 4 = Cuma; 5 = Huambo; 6 = Caluquembe [=Kalukembé]; 7 = Capelongo [=Kuvango]; 8 = Namibe [=Mossamedes, Moçâmedes]; 9 = Ondangua; 10 = Chitau; 11 = Ikelenge; 12 = Kalumbila; 13 = Murungu; 14 = Lubumbashi; 15 = Mufulira; 16 = Lake Bangeulu; 17 = Kawambwa; 18 = Manono; 19 = Kalemie; 20 = Fizi; 21 = Oshikango; 22 = Serra Jeci Grasslands; 23 = Zomba Plateau; 24 = Mlanje Mountain; 25 = Cholo Mountain; 26 = Misala; 27 = Nchisi Mountain; 28 = Chitala River; 29 = Salima;

predators occur at a lower density, the primary prey is more abundant, and they may experience less competition for resources ( Whiting et al. 2009).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Acanthocercus atricollis ( Smith, 1849: 14 )

| Wagner, Philipp, Greenbaum, Eli, Bauer, Aaron M., Kusamba, Chifundera & Leaché, Adam D. 2018 |

Acanthocercus atricollis ( Smith, 1849: 14 )

| Smith A 1849: 14 |