Eriptychius americanus, , PF, 1795

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06538-y |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8368398 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C0340F-FFD5-FF90-FCC0-F8D39BE94655 |

|

treatment provided by |

Julia |

|

scientific name |

Eriptychius americanus |

| status |

|

Eriptychius americanus walcott

,p. 167,plate 4, figures 5 –11

Type material. Seven isolated fragments of dermal bone embedded in matrix,collected by C.D. walcott from the Harding Quarry , Cañon City, Colorado,form the syntype USNM V 2350 in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in washington,DC, USA.

Emended diagnosis. Agnathan with mesomeric dermal tesserae and scales formed from acellular bone overlain by ornament formed from coarse wide-calibre tubular dentine.Body scales covered in multiple elongate ridges.Antorbital neurocranium comprising symmetrical set of elements containing numerous large canals internally, endoskeleton closely associated with but not fused to the surrounding dermal skeleton. Shared with Astraspis , arandaspids, other ‘ostracoderms’ excluding heterostracans:multiple branchial openings. Shared with Astraspis and tessellate heterostracans:dermal head skeleton formed from dorsal and ventral ‘headshields’ of ornamented tesserae.Differs from Astraspis in that ornament of dermal skeleton comprises ridges and presence of coarse tubular dentine.

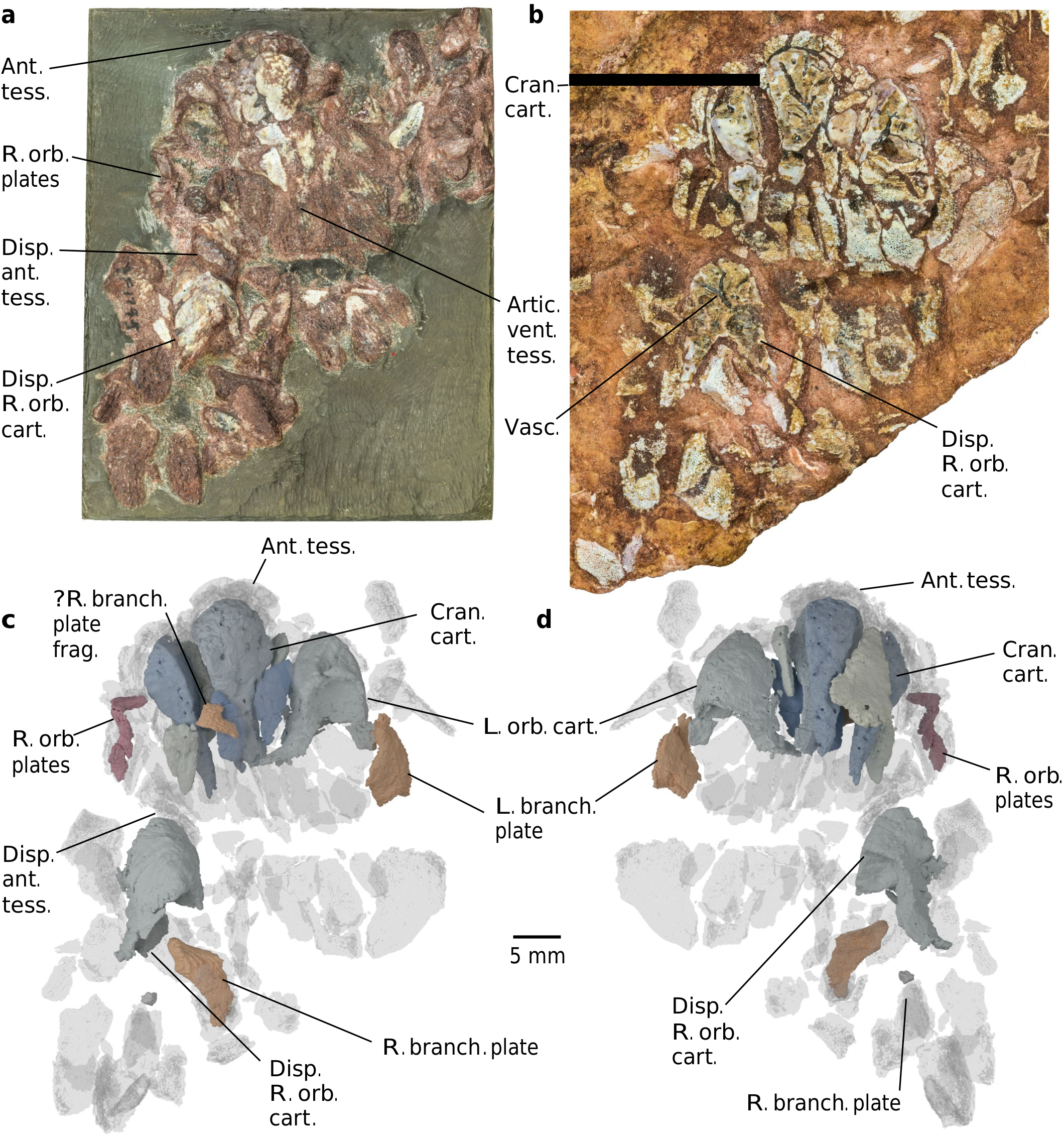

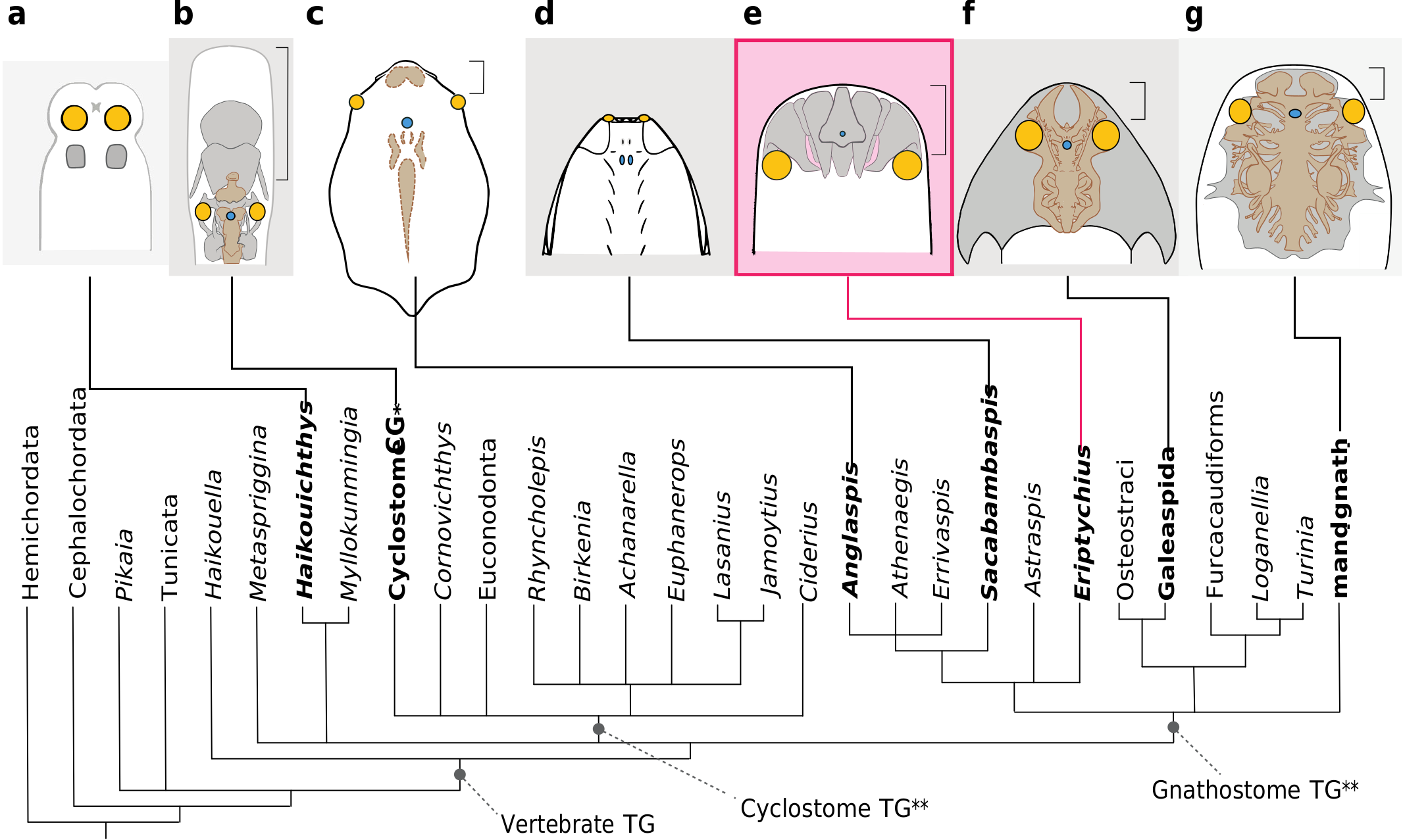

Description. Computed tomography scanning of the part and counterpart of PF 1795 (here termed PF 1795a and b, respectively;Methods) confirms the identity of this material as a partially articulated Eriptychius head 8, including components of both the dermal skeleton and endoskeleton ( Fig.1 View Fig , Extended Data Figs.1–3 View Fig View Fig and Supplementary Video;see Supplementary Information for comments on histology). The articulated individual is confined to the near surface of the matrix; below it is a mash of isolated elements typical of the Harding Sandstone bone beds including additional tesserae referable to Eriptychius that do not seem to be associated with the articulated specimen (Extended Data Fig. 1 View Fig ). Denison 8 described several large elements of globular calcified cartilage as part of the internal skeleton of Eriptychius and we have been able to distinguish ten separate cartilages in total comprising the endoskeletal cranium ( Figs. 1 and 2 View Fig and Extended Data Figs. 2 View Fig and 4).

Six cartilages were identified on the split surface of PF1795a by ref.8 (Extended Data Fig. 2 View Fig ) and the remaining four are buried within the matrix of PF 1795b. The cartilages are closely wrapped by articulated squamation anteriorly,dorsally and ventrally and to one side (Extended Data Figs.3 View Fig and 4); however,there is a clear separation between dermal and endoskeletal elements, unlike in galeaspids and osteostracans 36. This squamation comprises a range of dermal element types including the scale types identified by ref.8 and scales with an anteroposteriorly oriented ornament from farther back on the head.It also includes small, curved orbital plates( Fig. 1c,d View Fig and Extended Data Fig.3c–e View Fig ) and several plates similar in morphology( Fig. 1c,d View Fig and Extended Data Fig.3f–i View Fig ) to an isolated Eriptychius ‘branchio-cornual plate’ identified by ref. 37 (plate 2, 4–7). There is no obvious pineal dermal plate.

Denison identified two cartilages as the orbital cartilages on the basis of concave posterior faces 8. Our scan data confirm that these represent cross-sections through large fossae that we interpret as forming the anterior wall of the orbits.These fossae are flanked laterally by an antorbital process (Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Fig.5) that suggests a dorsolateral orientation of the orbit. A smaller ventral fossa on each orbital cartilage below the orbit may have provided a location for muscle attachment (Fig. 2). One orbital cartilage is posteriorly displaced, along with elements of anterior squamation including a rostral scale (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 3 View Fig ) and has rotated by about 180° in the sagittal axis;when rotated back into position it aligns with the orbital plates (Fig. 1). The anteriormost branchial plate lies posterolateral to the other orbital cartilage (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 3 View Fig ), suggesting that the relative positions of the orbits,otic region and branchial arches were similar to those inferred in heterostracans 2, 19, although this is impossible to judge exactly because of the collapse of the dermal skeleton.The absence of anything assignable to the branchial skeleton suggests that the branchial arches were not incorporated into a single mineralization with the neurocranium,a major difference with respect to galeaspids and osteostracans 7, 15.

The remaining cartilages lie between the two orbital cartilages, although they have slumped slightly and been pulled posteriorly on one side with the displaced orbital cartilage (Figs. 1 and 2a–c and Extended Data Fig. 4). There are three paired cartilages arranged symmetrically across the midline—two dorsal (termed mediolateral A, B) and one ventral (termed mediolateral C)—along with one unpaired midline cartilage dorsally and one ventrally.Of the two unpaired cartilages, the smaller dorsal element is kite-shaped and has both the dorsal and ventral surfaces punctured by large medial foramina that we consider likely to be the pineal opening (Fig. 2a,e). These dorsal and ventral foramina do not exactly line up anteroposteriorly but appear to communicate with a common large space inside the cartilage (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 6). This kite-shaped cartilage is preserved overlying the mediolateral cartilages A and its ventral surface bears a median ridge with a shallow depression on either side (Fig. 2a,e). Together with shallow depressions on the dorsal surface of mediolateral cartilages A, these depressions frame paired fossae which we interpret as having accommodated part of the forebrain, possibly the olfactory bulbs (Fig.2d–f), an interpretation consistent with their position relative to the orbits and putative pineal opening. Thus,we infer this to be the dorsal side of the animal and term this the median dorsal cartilage.The larger median ventral cartilage underlies the mediolateral cartilages.

All cartilages are pervasively penetrated by canals (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 6). In the larger cartilages,that is,the orbital cartilages and the mediolateral cartilages A,this tends to follow the pattern of a larger trunk entering the cartilage from the posterior side before splitting into smaller branches that open to the surface.The pattern is notexactlybilaterallysymmetricalinthepairedandunpairedelements but does follow a similar organization with the trunk canal entering at equivalent points. These canals could plausibly have carried sensory rami onto the surface of the head; for example, the superficial ophthalmic nerve in the case of the canals in the orbital cartilages. However,the canal openings are not restricted to surfaces where the cartilages contact the dermal skeleton.On the basis of this and the lack of sensory canal openings in the head tesserae,they may have carried vasculature instead or as well.In living chondrichthyans,canals carry vasculatureandtransportprechondrocytesintothecartilagefromthe perichondral surface.This could implicate the canals in Eriptychius in both cartilage maintenance and interstitial cartilage growth,although in modern chondrichthyans the width of these canals are an order of magnitudesmallerthanin Eriptychius 38, 39.Althoughcanalshavenotbeen explicitly reported in other early vertebrate cartilages,sections through galeaspid cartilage suggest that this tissue has a degree of vascularity 36.

In concert with the displacement of the cartilages,the dermal squamation has undergone postmortem collapse.we interpret the articulated area of squamation as having covered the right side of the head, around the region of the right orbit and the right side of the mouth,as well as the areas dorsal and ventral to the mouth ( Fig. 1 View Fig and Extended Data Fig.3 View Fig ).On the basis of this interpretation,the cartilages would have comprised the preorbital region of the head,surrounding the mouth ( Fig. 2c,h,i View Fig ). The articulated dorsal and ventral patches of squamation indicate that the mouth opened between the cartilages,bordered by the ‘rostral’ plates 8 and was oriented supraterminally ( Fig. 2c,h,i View Fig ), unlike most jawless stem-gnathostomes (notable exceptions being Doryaspis 40 and Drepanaspis 41).The fact that the cartilages are separate may mean that some movement of the oral endoskeleton was possible, although this would have presumably been limited by their close relationship with the squamation.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |