Simplimorpha ( Myrtinepticula ) sapphirella Remeikis & Stonis, 2018

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4521.2.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:B8EA1721-D5EF-4605-BA03-93E3CF255E3E |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5951415 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C087FA-104B-6002-7E85-D75B1761F9E3 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Simplimorpha ( Myrtinepticula ) sapphirella Remeikis & Stonis |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Simplimorpha ( Myrtinepticula) sapphirella Remeikis & Stonis , sp. nov.

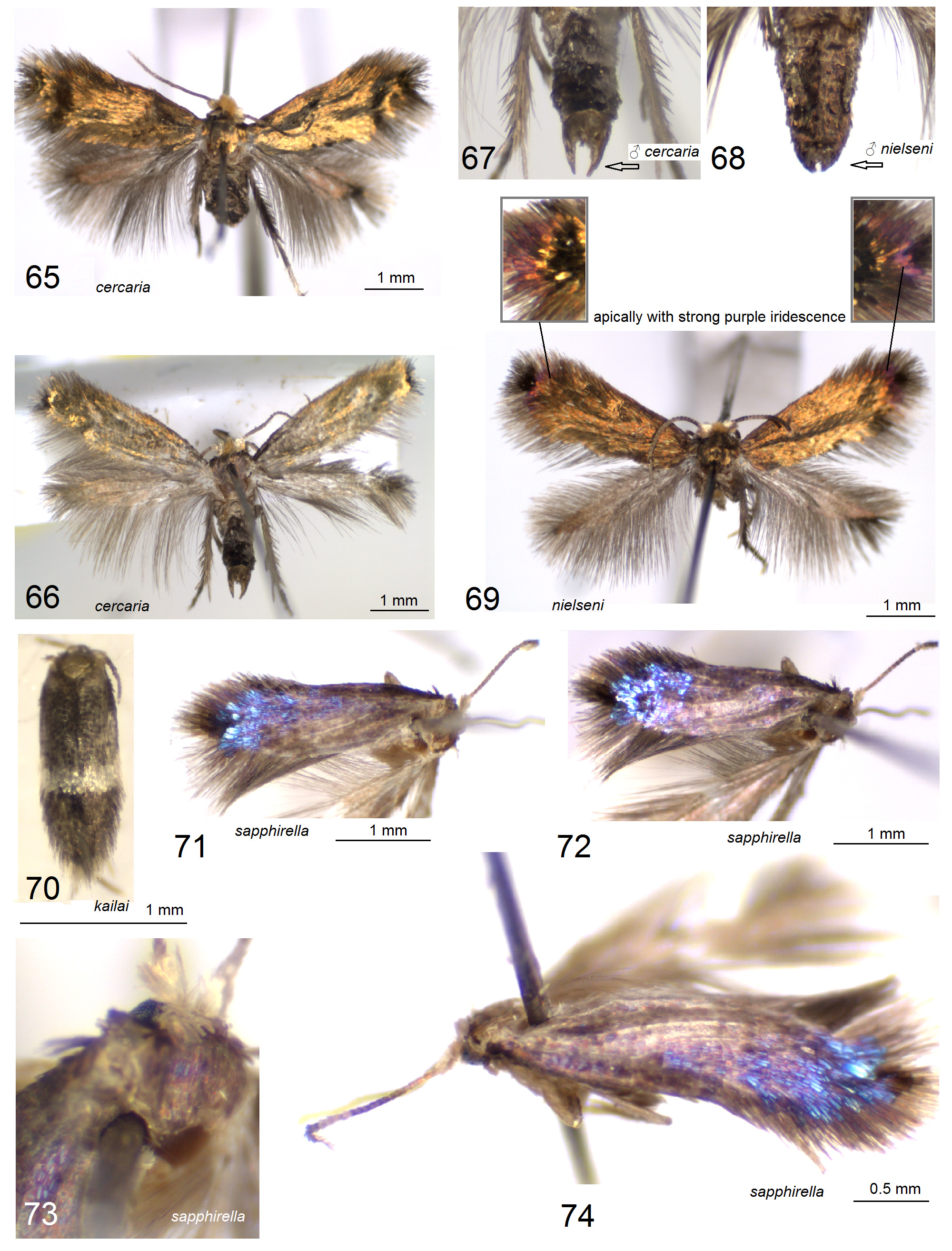

( Figs. 71–74 View FIGURES 65–74 , 126–129 View FIGURES 126–129 )

Type material. Holotype: ♀, CHILE, Cauquenes , Alto Tregualemu, 500 m., 10–12.i.1988, L. E. Peña G., genitalia slide no. RA 594♀ ( ZMUC).

Diagnosis. The combination of a fuscous brown forewing with strong blue iridescence and unique shape of distally broadened anterior apophysis in the female genitalia (see Fig.129 View FIGURES 126–129 ) distinguishes the species from all other congeneric Nepticulidae .

Male. Unknown.

Female ( Figs. 71–74 View FIGURES 65–74 ). Forewing length about 2.9 mm; wingspan about 6.6 mm. Head: palpi brownish cream to cream; frontal tuft brownish orange; collar large, comprised of lamellar scales, grey cream, glossy, with some purplish iridescence; scape golden cream; antenna half the length of forewing; flagellum with 28 segments, fuscous brown on upper side (except for the basal third and the tip which remain cream brown or grey cream), pale greybrown on underside. Thorax, tegula and forewing fuscous brown with very strong blue and some purple iridescence, particularly strong on apical half; fringe dark brown, with some slender lamellar scales overlapping; underside of forewing dark brown, with strong purple iridescence, without spots. Hindwing dark grey-brown to blackish brown with little purple iridescence on upper side and underside; fringe dark grey-brown. Legs glossy, brownish cream with a few dark scales on upper side of forelegs. Abdomen fuscous grey on upper side, brownish cream on underside.

Female genitalia ( Figs. 126–129 View FIGURES 126–129 ). Total length about 1200 µm. Anterior apophyses very broad, rounded and broadned distally; posterior apophyses rod-like. Vestibulum slender, without sclerites. Corpus bursae small (reduced), without pectinations or signum, oval-shaped. Accessory sac absent; ductus spermathecae with about 4.5 convolutions, extended into a slender, 710 µm long utriculus; spines or pectinations absent. Abdominal tip broad, truncate.

Bionomics. Adults fly January. Otherwise biology is unknown.

Distribution. This species occurs in the southern Andes ( Chile: Cauquenes) at an altitude about 500 m.

Etymology. The species name is derived from the Latin sapphires (sapphire) in reference to the very distinct blue iridescence of the forewing.

Remarks. There is no wing venation slide available. However, in the holotype, as far as is visible in the nondescaled specimen, the hindwing venation looks almost identical with that of S. nielseni . Additionally, the forewing venation also possesses the incomplete loop of vein A; distally there is one vein less in comparison to S. nielseni .

Discussion

Simplimorpha ( sensu lato) is characterized by a unique character, the strong (or usually total) reduction of a set of two functionally connected, but morphologically separate, sclerites of the male genitalia which is unknown in all other nepticulids. In Simplimorpha ( sensu stricto) and Roscidotoga , the reduced gnathos is represented only by two remnants (rudiments), i.e. very small lateral sclerites ( Figs. 7, 10), and in Myrtinepticula as a rudimentary transverse rod ( Fig. 11), or fully absent ( Fig. 12). The uncus appears totally reduced except for S. nielseni . However, Hoare (2000) hypothesized that the lobe-like lateral corners of the tegumen, each bearing a small number of setae, may represent a reduced uncus, which could be the case.

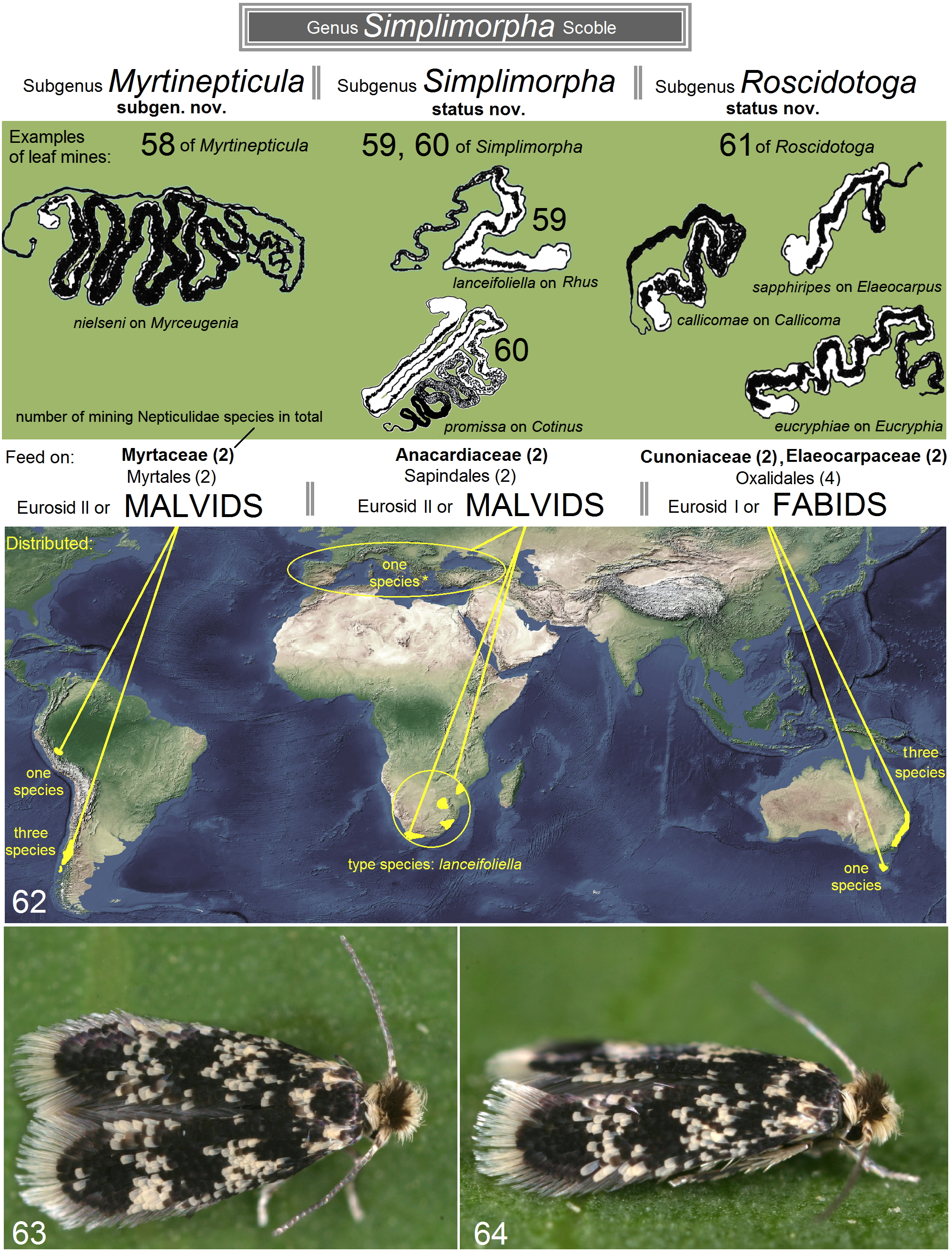

A scenario that the subgenera Simplimorpha Scoble , Roscidotoga Hoare and Myrticnepticula subgen. nov. may actually represent three different genera was also considered. However, their differentiation (see Figs. 1–49) depends only on minimal differences in the genitalia structures and host plant preferences. Therefore we consider a subgeneric ranking to be more appropriate, and for clarity of characters in the diagnostics of global Nepticulidae , we synonymize Roscidotoga with Simplimorpha , describe Myrtinepticula within Simplimorpha ( sensu lato), and hypothesize a Gondwanan origin for this genus (see Fig. 62 View FIGURES 58–64 ).

The male genitalia of Simplimorpha and Roscidotoga appear to be indistinguishable ( Figs. 1–4, 7–10, 13–17, 20–23, 26–33). Monophyly of Roscidotoga was originally diagnosed with nine characters ( Hoare 2000), but they are no longer valid with the current state of knowledge: 1) gnathos strongly reduced or lost (shared with Simplimorpha and Myrtinepticula ); 2) tegumen with appressed setose lobes (shared with Simplimorpha and Myrtinepticula ); 3) anterior extension of vinculum elongate (shared with Simplimorpha and Myrtinepticula , possibly even not an apomorphy); 4) phallus with one ventral and one dorsal process (shared with Simplimorpha and some Myrtinepticula ); 5) transverse bar of transtilla broken in middle (represents an intermediate state between Simplimorpha and some Myrtinepticula ); 6) pectinifer strongly reduced (it is possibly a misunderstood character, see below in the Discussion on Pectinivalva ); 7) in the female genitalia, anterior apophyses with expanded bases (shared with Myrtinepticula ); 8) corpus bursae with diverticulum (shared with Myrtinepticula ); 9) forewing with a silver streak from costa and apical suffusion of metallic scales (this is a variable character; in general, the forewing pattern often drastically varies from dull and unicolorous to metallic shiny with bright metallic markings even in very closely related species within the same species group, see Stonis et al. 2017).

Hoare (2000) emphasized the bluish to purplish iridescence of the forewing, combined with a triangular silver mark on the costa in the primary description of Roscidotoga which allowed the author to provide a nice name for the taxon. By using Latin roscidus (dewy) and toga (a garment), he suggested the name Roscidotoga . It should be noted that the predominantly Mediterranean Simplimorpha promissa also looks “dewy” ( Figs. 63, 64 View FIGURES 58–64 ) and South American Myrtinepticula are characterized by a strong blue or purple iridescence. However, as it was mentioned above, the scaling color characters are not reliable, especially at the genus level, and the genitalia characters now appear to be shared.

* one species on Paracryphiaceae (Hoare & van Nieukerken 2013)

Note: the morphological structures are drawn in different scales

The host-plant families of Roscidotoga , Cunoniaceae (incl. Eucryphiaceae ) and Elaeocarpaceae are considered to have formed part of the ancient angiosperm flora that covered large areas of Australia, Antarctica and South America in the late Cretaceous and early Tertiary when these continents were still joined as part of the supercontinent Gondwana ( Hoare 2000). Myrtaceae is also an old Gondwanan family, with a long history in southern continents ( Johnson & Briggs 1984).

Most of the taxonomic work on the Nepticulidae has dealt adults but not the larval stages. Although Hoare (2000) described the larva of Roscidotoga , it is not possible to compare larval data because of the lack of larval studies of the type species of Simplimorpha and any species in Myrtinepticula .

Previously, Roscidotoga was believed to be a sister-group to Pectinivalva Scoble (van Nieukerken et al. 2011; Hoare & van Nieukerken 2013; Doorenweerd et al. 2016). It is obvious that the male and female genitalia of Roscidotoga ( Figs. 3, 4, 9, 10, 15–17, 22, 23, 29–33, 41–44) and Pectinivalva ( Figs. 130–159) have no characters in common, except for the ground plan characters of Nepticulidae . Seven synapomorphies of Roscidotoga + Pectinivalva listed by Hoare (2000), mainly on interpretations of the wing venation and details of morphology of immature stages, are problematic. Therefore, we cannot adopt the sister-relationship concept or the hypothesized Pectivalvinae ( Scoble 1983, Hoare & van Nieukerken 2013). There is no description of the subfamily Pectinivalvinae with well-defined characters. The monophyly of the expanded Pectinivalvinae ( Pectinivalva + Roscidotoga ) was also questioned earlier ( Puplesis & Diškus 2003 ).

These problematic issues regarding Pectinivalva have broadly hindered the consistency of ranking within the general framework of the generic composition of the Nepticulidae and the need for easy differentiation and/or diagnostics of the global Nepticulidae . In 2013, Pectinivalva was divided into three subgenera: Pectivalva Scoble, Casanovula Hoare , and Menurella Hoare (Hoare & van Nieukerken 2013), each of which was elevated to a genus rank later (van Nieukerken et al. 2016a). In our work, taxa that share apomorphic characters, are regarded as being closely related. For practical reasons, genera should be well-distinguishable based on characters. Pectinivalva , Casanovula and Menurella exhibit no substantial differences ( Figs. 130–159), include so-called intermediate species, and are distributed in generally the same region ( Australia and adjacent areas, including Borneo), with probably the same time of their origin (see Doorenweerd et al. 2016). The close relationship of Pectinivalva , Casanovula and Menurella is further reinforced by the shared host-plant family ( Myrtaceae ). Eucalyptus L'Hér. is a host-plant genus for at least some, if not all species, of these three Nepticulidae taxa. With a few exceptions, related taxa of Nepticulidae feed on host plants that are themselves related. We appreciate that this could make them at least subgenera, but it seems that the differences in external characters (like a forewing pattern) are not enough. Small differences in wing venation could be a result of independent reduction in these tiny moths (on the other hand, the venation characters are difficult to apply and/or use in every-day species diagnostic practice), and differences in the remaining morphology are so small for the taxa even to be called subgenera. It is interesting to note that in the molecular phylogenetic tree there is no obvious support for taxonomic status of these three genera, except as informal species groups as was admitted by Hoare & van Nieukerken (2013). An expanded molecular study would be particularly worthwhile. Therefore, because of the distinct similarity and difficulty to diagnose, all three previously erected genera now are merged into Pectinivalva Scoble ( sensu lato) ( Figs. 130–159).

Subgenera allow us to convey more information about the characters and relationships of species within a genus. In van Nieukerken et al. (2016a), subgeneric ranks were abandoned and subgenera were elevated to genera, except for Levarchama Beirne , because the previous classification system (van Nieukerken 1986) was not supported by molecular treatments, particularly in the case of artificial conglomerates such as Ectoedemia Busck , sensu lato (van Nieukerken et al. 2016a).

| ZMUC |

Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |