Amphiglossus meva, Miralles, Aurélien, Raselimanana, Achille P., Rakotomalala, Domoina, Vences, Miguel & Vieites, David R., 2011

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.277878 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5631210 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C187CA-FFCC-FFED-FF3A-FED8FDDC9D0C |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Amphiglossus meva |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Amphiglossus meva sp. nov.

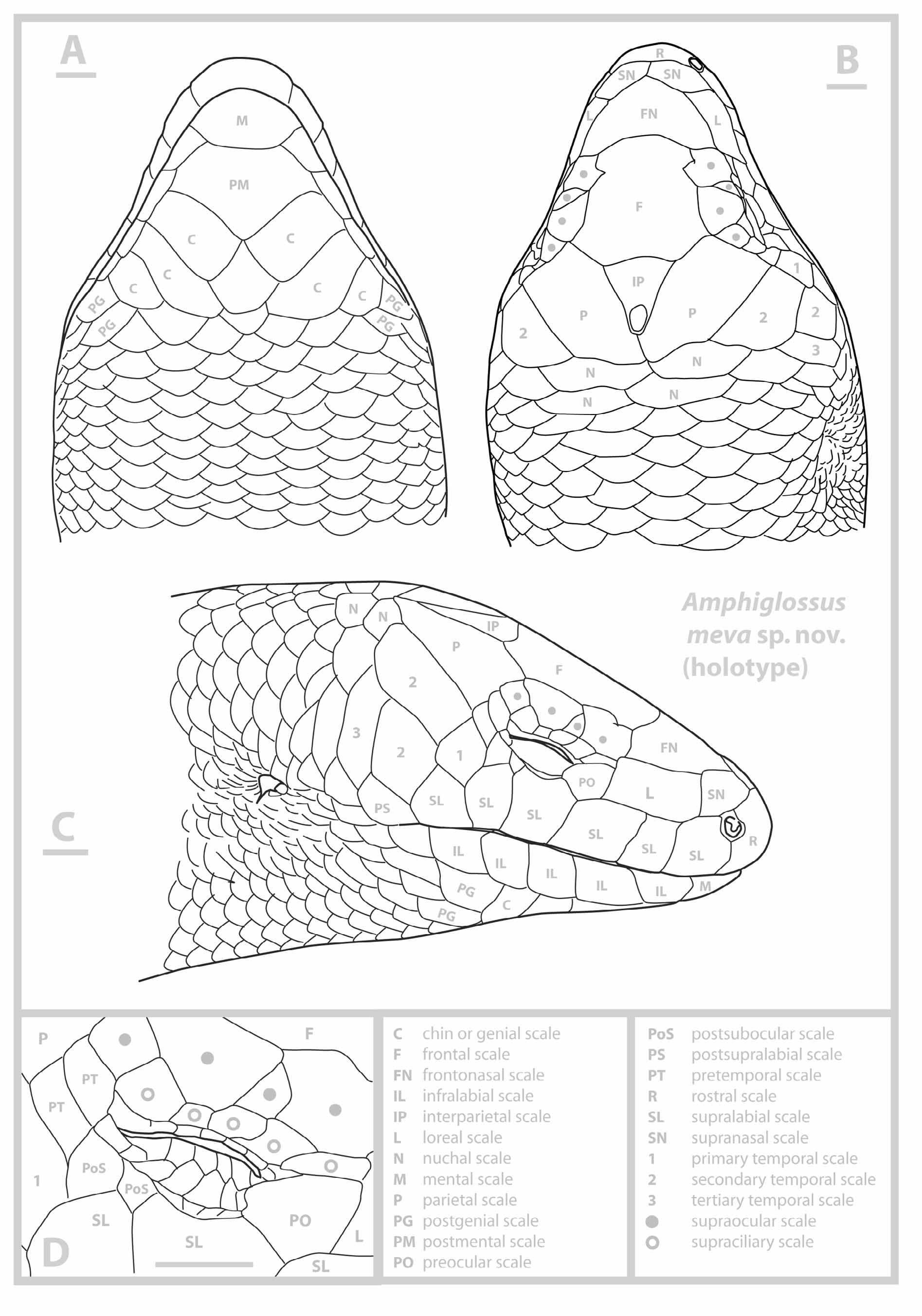

(figs. 2, 3)

Holotype. MNCN 44648 (field no. ZCMV 11324), collected in the western portion of the Makira plateau, close to a campsite locally named Angozongahy, at 15°26'13.3''S 49°07'07.0''E, 1009 m above sea level, district of Mandritsara, region of Sofia, province of Mahajanga, northeastern Madagascar, by D.R. Vieites, M. Vences, F. Ratsoavina and R.-D. Randrianiaina on 28 June 2009. The holotype is in a good state of preservation; it was fixed and preserved in alcohol. At the time of preservation the specimen was shedding, which explains the somewhat faded coloration.

Paratypes (n=10). One adult specimen, MNCN 44650 (field no. DRV 5947), a subadult, MNCN 44649 (field no. DRV 5885), and a juvenile, ZSM 0487/2009 (field no. ZCMV 11323), collected by the same collectors and at the same locality as the holotype; a juvenile, UADBA 29402 (field no. APR 05957), collected on 24 November 2004 in the transitional rainforest at Riamalandy, 16°17.1’S 48°48.9’E, 850 m elevation within the RS of Marotandrano, Region of Sofia, Madagascar, by A. P. Raselimanana; a juvenile, UADBA 29403 (field no. APR 05958) and an adult male, UADBA 29404 (field no. APR 05959), collected at the same date and in the same area as above, but both were found together in a different rotten log, by A. P. Raselimanana; an adult male, UADBA 29405 (field no. APR 06021) captured on 26th November 2004 in the transitional rainforest at Riamalandy, same conditions as above, by A. P. Raselimanana; an adult female, UADBA 29406 (field no. APR 06039) and two juveniles, UADBA 29407 and UADBA 29408 (field no. APR 0 6040 and APR 06041), collected in the same rotten logs on 27th November 2004 in transitional forest at Riamalandy, 16°16.9’S 48°49.1’E, 800 m elevation within the RS of Marotandrano, Region of Sofia, Madagascar, by A. P. Raselimanana.

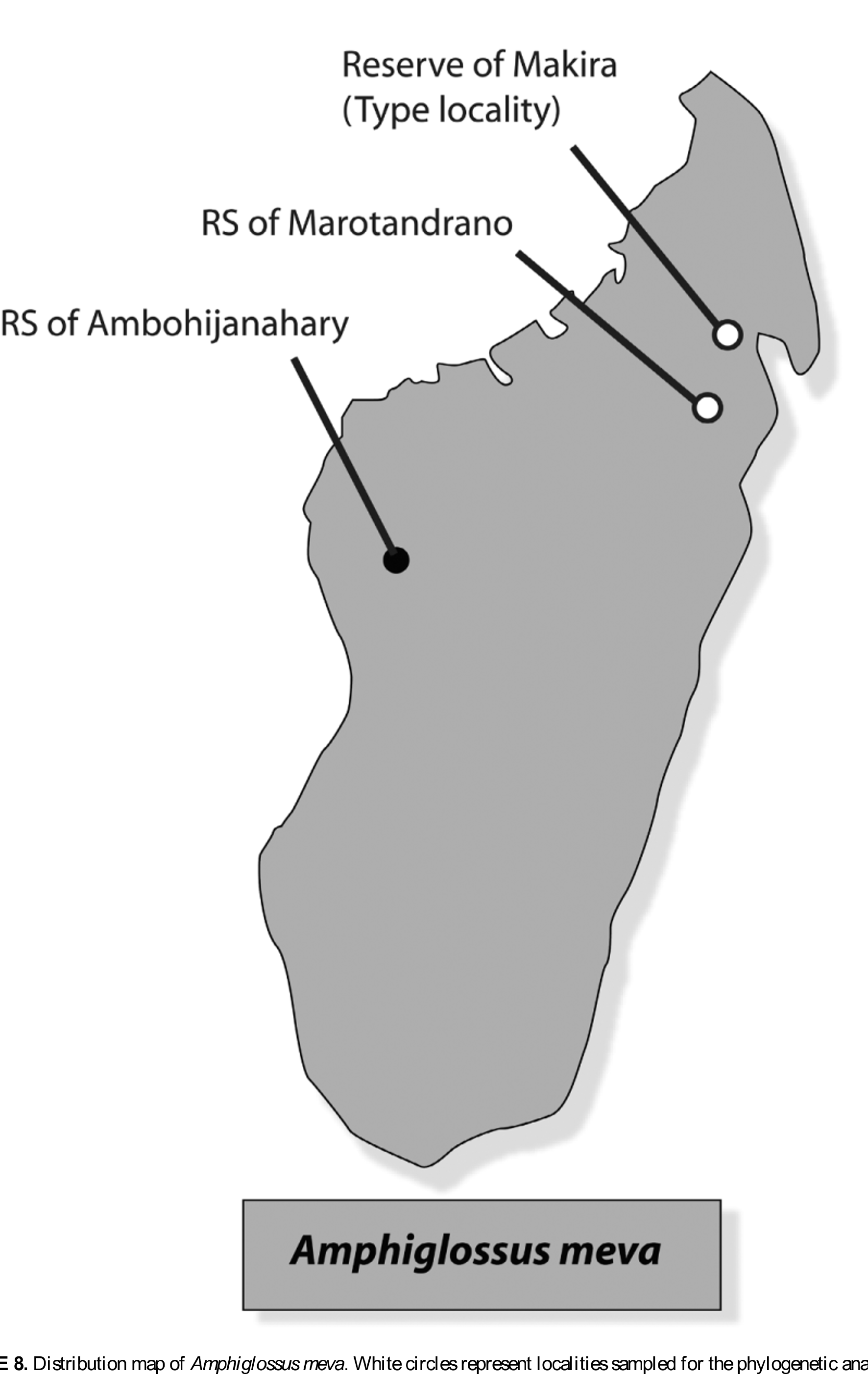

Additional specimens (n=2). Two additional specimens were collected in the RS of Ambohijanahary. We refrain to include these specimens in the type series given that (1) this locality is far away from both the Makira reserve and the RS of Marotandrano, (2) these specimens have a narrower brown dorsal stripe than those from Makira and from the RS of Marotandrano (6 scales rows vs. 10) and (3) no tissue sample from this locality was available for molecular analysis. These specimens are: an adult male, UADBA 12209 (field no. RD 1225) and an adult female, UADBA 12210 (field no. RD 1269) in excellent condition of preservation, collected on 18 and 19 December 1999, in the “forêt d’ Ankazotsihitafototra”, 18°15.7’S 45°25.2’E, 1150 m elevation within the RS of Ambohijanahary, Region of Bongolava, Madagascar, by D. Rakotomalala and S. M. Goodman.

Diagnosis. A member of the phenetic Amphiglossus / Madascincus group which differs (1) from the Malagasy genera in the subfamily Lygosominae ( Cryptoblepharus and Trachylepis ) by the presence of entirely movable and scaly eyelids (versus fused immovable eyelids forming spectacles over the eyes in Cryptoblepharus ; or movable eyelids with a translucent disk or window in the lower eyelid in Trachylepis ), absence of prefrontals (present in both Cryptoblepharus and Trachylepis ), and lack of frontoparietal scales (present in Trachylepis ); (2) from all the other Malagasy scincine genera by the presence of four legs.

Within the Amphiglossus / Madascincus group, it is placed in the lineage called Amphiglossus (sensu Crottini et al. 2009) by molecular data. Within Amphiglossu s, it is distinguished from all the other species by a combination of (1) a relatively large size (SVL of adults from 126 to 150 mm); (2) a characteristic pattern of coloration with dark/ grey dorsum contrasting with bright orange to yellowish flanks and ventrum, including the ventral side of the tail; (3) absence of a postnasal scale; (4) presubocular frequently absent, (5) presence of a single elongated tertiary temporal bordering lower secondary temporal.

Among large-sized Amphiglossus ( A. astrolabi , A. reticulatus , A. ardouini , A. mandokava , A. crenni ), the new species can be distinguished from the superficially similar Amphiglossus astrolabi (see fig. 4A, 5A–D) by showing significantly shorter fingers and toes with lower numbers of lamellae under fourth finger (6–8 versus 10–13) and fourth toe (11–13 versus 15–21); a smaller size (SVL max = 150 mm versus 226 mm); more compact head; a lower number of ventrals (91–96 versus 99–113); absence of postnasal; presubocular frequently absent (versus always present, most often two on each sides). From A. reticulatus (see fig. 5E–H) it can be distinguished by showing significantly shorter limbs in proportion to body size; smaller size (SVL max = 150 mm versus 212 mm); a less prominent parietal area and more compact head; a lower number of ventral scales (91–96 versus 95–108) and of scale rows around midbody (32–36 versus 39–41); absence of postnasal; by the uniform dark dorsal and light ventral coloration (versus complex patterns). From A. ardouini it differs by the absence of postnasals (versus presence), a higher number of scale rows around midbody (32–36 versus 31–33), shorter fingers with a lower number of lamellae under fourth finger (6–8 versus 7–10) and toe (9–13 versus 17–21), a uniform dark dorsal and light ventral coloration (versus complex patterns, including dark transversal dark stripes in the anterior part of body). From A. mandokava it differs by the absence of postnasals (versus present), a lower number of ventrals (91–96 versus 103– 120) and paravertebrals (95–101 versus 129–141), by the uniform dark dorsal and light ventral coloration (versus complex patterns, including dark transversal dark stripes in the anterior part of body). From A. crenni (see fig. 4B, 6), it differs by the absence of postnasals (versus presence); a more compact body with 32–36 scales around midbody (versus a slender elongated body with 26–28 scales around mid-body), and pentadactyl limbs (versus extremely reduced limbs, usually with two toes and two fingers, but sometimes with up to four). See also table 2 for a summary of morphological characteristics of the new species. Furthermore, the new species differs from all Amphiglossus and Madascincus species for which DNA sequences were available, by high sequence divergences in mitochondrial and nuclear genes (see below).

Postnasals Present 100% 100% X 100% 100% –

Absent – – – – – 100%

N sides (8) (24) (1) (10) (12) (26) Presubocular N=0 – – – – – 42,3%

N=1 100 % 25% X 100 % 100 % 57,7%

N=2 – 75% – – – –

n sides: (4) (24) (1) (10) (12) (26) 1Partly based on Angel (1942) and Brygoo (1983). 2 Based on Andreone & Greer (2002) and on the photographs of the lost holotype taken by Brygoo in 1976 (see fig. 6). 3Partly based on Raxworthy & Nussbaum (1993). 4Two types of color patterns are presently distinguished: (1) the “bicolor pattern” with a dorsal side uniformly dark contrasting with a ventral side uniformly light, and (2) the “variegated patterns” that may be composed by dark transversal or longitudinal stripes, dash lines, or reticulations on a lighter background.

Description of the holotype. MNCN 44648 (field number ZCMV 11324) ( Fig 2 View FIGURE 2 , 3 View FIGURE 3 A). In general appearance, a medium to large-sized Amphiglossus skink, assigned to this (paraphyletic) genus on the basis of molecular phylogenetic relationships and presence of pentadactyl limbs; snout–vent length (143.0 mm), 6.5 times head length (21.9 mm), almost as long as tail length (136 mm, tip regenerated). Both pairs of limbs short, pentadactyl, with very short fingers; as a proportion of SVL, front limb 14% (20– 19.5 mm) and rear limb 17% (24.5–26.2 mm).

Snout bluntly rounded in both lateral and medial aspect; rostral wider than high contacting first supralabials, nasals and supranasals. Paired supranasals in median contact, contacting loreal. Frontonasal triangular, wider than long, posterior side concave, contacting loreals and first suproculars. Prefrontals absent. Frontal quadrilateral, as long as wide becoming wider at the posterior part. Supraoculars four, the second one is significantly reduced, the first and third are barely in contact medially, the fourth supraocular is also reduced; first supraocular constricting frontal (frontal hourglass-shaped sensu Andreone & Greer 2002), the first and the third supraoculars contacting frontal. Frontoparietals absent. Interparietal present, well separated from supraoculars and of triangular shape, longer than wide; parietal eye evident. Parietals contact posterior to interparietal. Two pairs of enlarged nuchals. Nasal an anteriorly open ellipsis, just slightly larger than nostril, in contact with rostral, first supralabials and supranasals. Postnasal absent, probably fused with first supralabials. Loreal single, longer than higher. Preocular single; presubocular absent. Supraciliaries five, in continuous row, first and last pairs significantly larger and longer than the intermediate ones; last pair projecting medially into supraocular series (thereby greatly reducing fourth supraocular in size); upper palpebrals small except for last which projects dorsomedially slightly. Pretemporals two, both contacted by parietal; postsuboculars two, the first reduced, upper contacting lower pretemporal, both contacting penultimate supralabial. Lower eyelid moveable, scaly; lower palpebrals small, longer than high, interdigitating with large columnar scales of central eyelid; contact between upper palpebrals and supraciliaries direct but flexible, i.e. palpebral cleft narrow. Primary temporal single. Secondary temporals two, upper long, contacting lower pretemporal anteriorly and the first pair of nuchal posteriorly and overlapping lower secondary temporal ventrally; tertiary temporal single, bordering lower secondary temporal, dorsoventrally elongated, and posteriorly followed by a scale slightly smaller and similar in shape. Supralabials six, the fourth being the subocular which contacts scales of lower eyelid. Postsupralabial single, external ear opening approximately half size of eye opening, circular to horizontally suboval, with short, narrow, blunt lobules anteriorly (at least three evident, the first one being the biggest). Mental twice wider than long; postmental diamond shaped, wider than long, contacting two infralabials. Infralabials five. Three pairs of large chin scales, members of first pair nearly in contact medially, members of second pair separated by one scale row, and members of third pair separated by five scale rows. Two asymmetrical postgenials posterolaterally in contact with the third pair of chin scales. Gulars similar in size and outline to ventrals. All scales, except head shields and scales on palms, soles, and digits, cycloid, smooth, and imbricate; longitudinal scale rows at midbody 35; paravertebrals 98–99, including nuchals, similar in size to adjacent scales; ventrals 92, including the preanals and postmentals; larger inner preanals overlap outer smaller; scales of midventral caudal series similar in size to more adjacent scales. Both pairs of limbs pentadactyl; fingers and toes very short, clawed. Subdigital lamellae smooth, single, with 7/8 subdigital lamellae beneath fourth digit of hands, 11/11 subdigital lamellae beneath fourth digit of feet.

Color in life. The color in life is similar to the color in preservative as described below, except the scales of the flanks that showed a faded orange coloration which was lost when preserved in ethanol. The orange was present in the central portion of the scales, with the posterior border creamy-whitish.

Color in preservative. Background color of the upper side of the head, neck, back, limbs, and tail light grey/ brownish. Venter, lower side of head, throat, lower side of limbs, tail and flanks are creamish, with the flanks slightly darker than venter. The limit between the dorsal coloration and the flanks shows a little contrast, which was more evident in life. Dorsal scales show lighter posterior edges, and the grey/brownish coloration comprises ten dorsal scales in wide. On the head, the area between the ear opening and the eye, including the two posteriormost supralabial, post-supralabial and the lower temporals, are whitish (the same coloration as the throat), contrasting with the rest of the dorsal side of the head. On all limbs, the dark coloration of the upper part does not connect with the dorsum, having an area in the proximal part of the limb with light-cream coloration. The coloration of the palms and feet is slightly darker than the ventral coloration. The rostral, first supralabials and the supranasals scales show a contrasting milky or semi-translucid coloration, with a clearer whitish dot on the central part of the rostral.

Intraspecific variation. The following summary of the variation in meristic and mensural characters gives the range for each of them, followed by the mean, ± the standard deviation, and sample size in parentheses. For some bilateral characters, the sample size has been noted as the number of sides rather than specimens, and this is then indicated after the sample size. Ventrals scales rows: 91–96 (93.23 ± 1.48, n=13); paravertebral scales rows: 95– 101 (98.30 ± 2.13, n=13); longitudinal scale rows at mid-body: 32–36 (34.38 ± 1.12, n=13); lamellae under 4th finger: 6–8 (6.85 ± 0.67, n sides=26); lamellae under 4th toe: 9–13 (11.23 ± 1.11, n sides=26); SVL adults: 126– 150mm (140 ± 8.0, n=7), with a minimal SVL of 68 mm recorded on a juvenile; supralabials (n sides=26): most often six supralabial (88.46%), sometimes five (11.53%); postsupralabials (n sides=23): always single (100%); infralabials (n sides=18): most often five (72.2%), sometimes four (16.7%) or six (11.1%); supraoculars (n sides=26): most often four (84.6%), sometimes three (7.7%) or five (7.7%), number of supraoculars in contact with the frontal (n sides=26): most often three (73.1%), sometimes two (19.2%) or four (7.7%); supraciliaries (n sides=24): most often five (50%), sometimes six (29.2%) or seven (20.8%); loreals (n sides=26): always single (100%); postnasals (n sides=26): always absent (100%).

Most of the specimens show the contrasting milky coloration on rostral, first supralabials and the supranasals scales as in the holotype. Juveniles frequently show a whitish patch on the anterior supraciliary area. Specimens from the western population (Ambohijanahary) have a narrower dark dorsal stripe (always six scale rows on the neck, n=2) than those from Makira and Marotandrano (always ten scale rows on the neck, n=11). The life coloration of juveniles is similar to the adults, with a bright contrasting orange / pink on the flanks, venter, lower side of head, throat, lower side of limbs, and tail. Nevertheless, in Makira, the pattern shown by the available series of specimens suggests that the orange coloration fades in parallel with the age of the specimen, what does not seem to be the case in the populations of Marotandrano and Ambohijanahary. In all specimens, the orange coloration disappeared after fixation, becoming cream or peach colored. See also table 2.

Etymology. Meva , pronounced “maeva or moeva”, is a Malagasy word used to express beauty and refers to the splendid bicoloration of this skink. It is used as a noun in apposition.

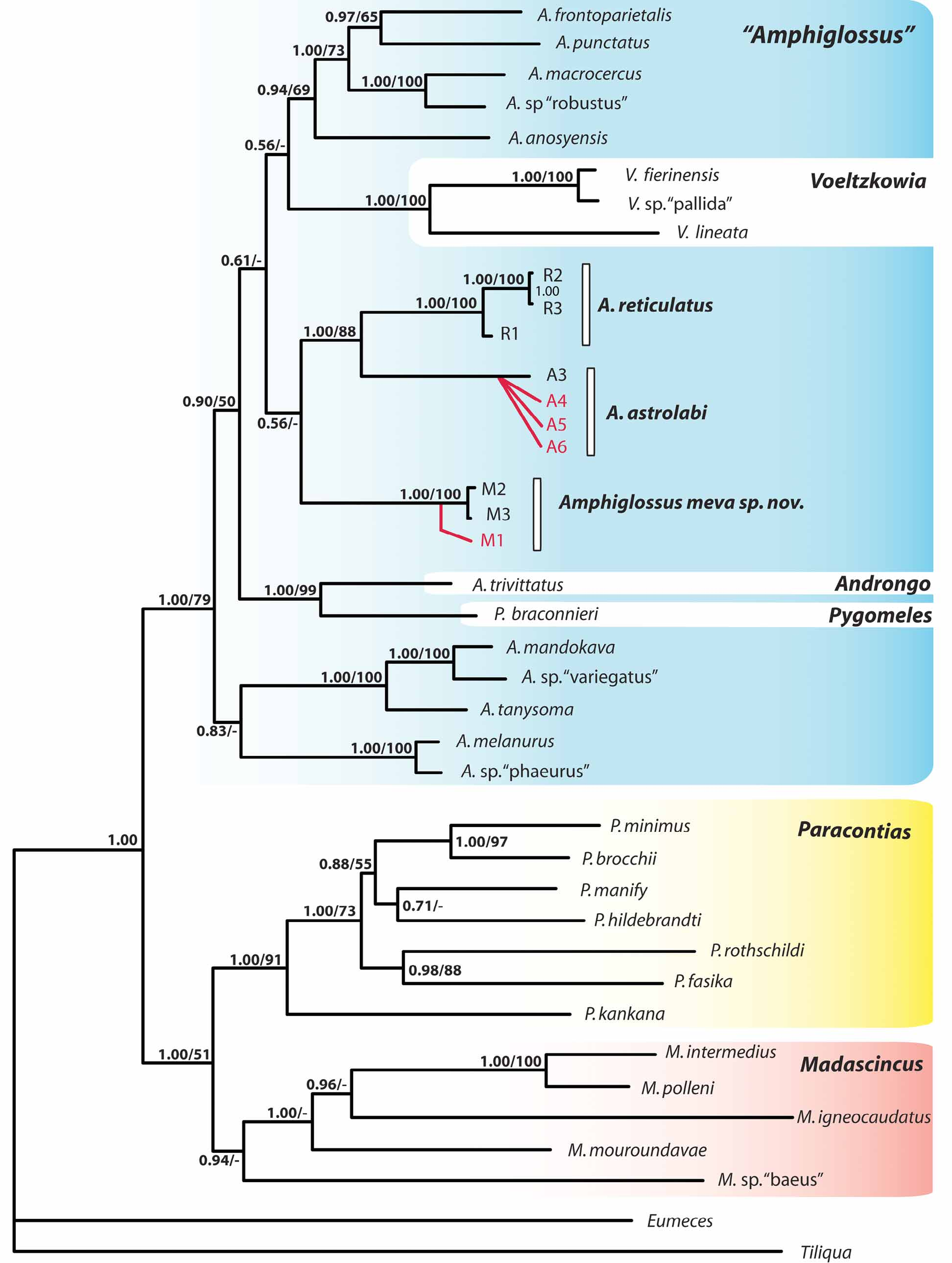

Phylogenetic position and genetic differentiation. The results of the phylogenetic analyses are summarized in Figure 7 View FIGURE 7 . Unsurprisingly, the phylogenetic tree obtained is highly congruent with the one published by Crottini et al. (2009). Although many of the most basal nodes of the genus Amphiglossus are insufficiently supported to reliably infer the exact position of the new species within this taxon, some significant results may be formulated: (1) both MP and Bayesian analyses gave results congruently supporting the placement of A. meva within the genus “ Amphiglossus ” sensu Crottini et al. (2009), with a bootstrap support value of 79% and a posterior probability of 1.00; and (2) the results show that Amphiglossus astrolabi is more closely related to Amphiglossus reticulatus (88%; 1.00) than to Amphiglossus meva .

The uncorrected p-distances ( Table 3 View TABLE 3 ) estimated between Amphiglossus meva and Amphiglossus astrolabi (p - distances ranging between 7.4% and 8.3% for the 16S gene, and between 14.4% and 15.3% for the ND1 gene) or between Amphiglossus meva and Amphiglossus reticulatus (5.5% to 5.8%, and 11.3% to 12.0%, respectively) are of the same order of magnitude as those observed between Amphiglossus astrolabi and Amphiglossus reticulatus (6.00% to 7.10%, and 12.90% to 14.20%, respectively).

clade, estimated from 16S and ND1 sequences. Range, followed by mean ± standard deviation and sample size (inside paren-

theses) are given for both intra- and interspecific comparisons.

Habitat and distribution. In the Makira reserve, despite the use of pitfall lines, no specimen of A. meva was collected in pitfall traps. Instead, all individuals were caught in a flat valley area not too far from a stream, at sites that during the rainy season are probably flooded, but that during our visit (in the dry period) did not have any water or wet soil. All specimens were found within or under large logs, which typically were largely rotten and which maintained a certain degree of humidity without being soaked with water. The collecting site was on the main plateau of Makira, which is made up by a vast rainforest area at an altitude between 900-1200 m above sea level. The collecting site was characterized by a herpetofaunal composition typical for the mid-altitude eastern rainforests of Madagascar, whereas within a few kilometers, on the western slopes of the plateau, a drastic ecotone towards the drier areas of western Madagascar occurs, characterized by numerous herpetofaunal elements typical for western and northern Madagascar, such as the frogs Mantidactylus ambreensis and M. ulcerosus and the gecko Paroedura oviceps (a comprehensive account of the results of our survey at Makira will be published elsewhere). In the RS of Ambohijanahary, the specimens UADBA 12209 and 12210 (not included in the type series) were captured in the same pitfall bucket, which was part of a line within the bottom of a forested valley, 5 m away from a small stream, and 50 m away from the forest edge. In this area, the vegetation is the typical mid-elevation (1150 m) primary rainforest, within the category western humid forest ( Moat & Smith 2007). The RS of Ambohijanahary is located along the extreme western portion of the Central Highlands, within the Bongolava chain, approximately 80 km NW of the town Tsiroanomandidy. This forest shows some transitional vegetation elements between two phytogeographic subdivisions of the Western and Central Domains ( Nicoll & Langrand 1989), and can be attributed to the humid vegetation ( Moat & Smith 2007). The specimens were collected from the RS of Marotandrano at Riamalandy, located in the northern region of Madagascar, about 12.5 km SSW of the Commune rurale de Marotandrano. The habitat is a closed canopy midelevation (800–850m) transitional rainforest with humid vegetation ( Moat & Smith 2007) associated with taller trees and forest floor rich in organic material with thick leaf litters and diverse detritus. All specimens were found in large and humid rotten logs, in valley closed canopy rainforest during refuge examination. Three pitfall lines with drift fence were used during the survey, but no individuals of this species were caught.

Previous herpetological surveys using pitfall traps in the same reserve (Raxworthy, unpublished; Biodev, unpublished), the Central Highland sites of the RS d'Ambohitantely (C.J. Raxworthy and collaborators and S.M. Goodman and collaborators, unpublished), Ankazomivady forest ( Goodman et al., 1998), Parc National d’Andringitra ( Raxworthy et al., 1996), and Andranomay forest (Raselimanana 1998), the west part of Parc National du Tsingy de Bemaraha ( Bora et al. 2010), Kirindy forest ( Raselimanana 2008, Raxworthy et al, unpublished), the southwestern PK 32 forest (Raxworthy et al., umpublished,), Parc National de Zombitse (Raxworthy et al. 1994), and Vohibasia ( Goodman et al. 1997), and the northwestern RS d'Ankarafantsika ( Ramanamanjato & Rabibisoa, 2002; Raselimanana, 2008) did not provide any evidence for the occurrence of A. meva n. sp. although numerous other burrowing species (skinks and frogs) were collected in these surveys. The species appears to show a preference for large rotten logs retaining a certain degree of humidity but in general in parts of the rainforest with relatively dry soils. Based on our finding in Marotandrano and Makira, this new species is not rare but probably has a quite strict ecological specificity with respect to its microhabitat ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ).

Ecological notes. In Ambohijanahary, two specimens were captured on two consecutive days, both in the same pitfall trap, 5 m away from a 2 m wide stream. They may have been a breeding pair. No other individuals were found in the RS d’Ambohijanahary despite an additional 165 trap days with pitfall devices. The specimens from Marotandrano were all captured during refuge examination including rotten logs excavation and removal of barks and leaf litter accumulated under taller and big dead trees. In Makira, a group of three individuals was found together under a big log. Several larvae of coleopterans, other insects and termites were found in the same microhabitat, suggesting that this new skink may feed on these preys. In contrast to the other large species within the same genus, A. meva was never found in water.

Threats and Conservation status. Habitat loss due to slash and burn agriculture, bush fires, and wood extraction are the main pressures on the Ambohijanahary and Marotandrano reserve. Forests at these reserves, especially Ambohijanahary, are extensively fragmented. Although this forest is classified as a Réserve Spéciale, no management plan has been proposed. The reserve and surrounding areas are known to be the domain of zebu cattle thieves (dahalo). The forested areas within the reserve are often used by local people as a site to shelter stolen zebu. The importance of this form of refuge has provided some protection to the remaining forest. Moreover, MNP has an office and agents in Marotandrano Village and a coordination office is operational in Mandritsara. On the contrary, Makira reserve currently appears to be relatively well preserved at its western edge, where the type locality of the new species is located. Despite the common use of the forest for cattle grazing, in 2009 we could not detect major forest destruction nor human settlements directly in the forested area. Efforts need to be undertaken to maintain this apparently stable situation and to reduce forest destruction at the eastern lowland borders of Makira, which appears to be relatively intense in some areas.

TABLE 3. Summary of genetic divergence (uncorrected p-distances) within the “ Amphiglossus astrolabi / meva / reticulatus ”

| 16S | ND1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Intraspecific distances within: Amphiglossus astrolabi Amphiglossus meva Amphiglossus reticulatus | 0.2 – 2.1 (1.37 ± 1.02; 3) 0.0 (0.0; 3) 0.0 – 0.7 (0.47 ± 0.40; 3) | 2.0 – 2.1 (2.00 ± 2.04; 6) 0.0 – 0.2 (0.13 ± 0.11; 3) 0.0 – 2.7 (1.80 ± 1.55; 3) |

| Interspecific distances between: A. astrolabi / A. meva A. astrolabi / A. reticulatus A. meva / A. reticulatus | 7.4 – 8.3 (7.70 ± 0.45; 9) 6.0 – 7.1 (6.52 ± 0.41; 9) 5.5 – 5.8 (5.60 ± 0.15; 9) | 14.4 –15.3 (14.94 ± 0.31; 12) 12.9 –14.2 (13.62 ± 0.65; 12) 11.3 –12.0 (11.60 ± 0.27; 9) |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.