Tragulus kanchil (Raffles, 1822)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5721279 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5721307 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C587E3-1E78-FF93-FA55-FE4F95CFF679 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Tragulus kanchil |

| status |

|

Lesser Indo-Malayan Chevrotain

French: Chevrotain kanchil / German: Kleinkantschil / Spanish: Ciervo ratén pequeno

Other common names: Kancil

Taxonomy. Moschus kanchil Raffles, 1822 , Bengkulu, Sumatra, Indonesia. Lesser Indo-Malayan Chevrotains are highly variable in coloration, especially the taxa from small islands. This has led to the description of a great number of species and subspecies. A taxonomic review in 2004 brought some clarity about the validity of the many described taxa. Still, many type specimens, especially of small island taxa, were not included in that review, and the authors were unable to assess the validity of all taxa. This includes Sfulvicollis from the Malacca Strait islands (Bengkalis, Padang, Rupat, Tebingtinggi, and Rangsam); pallidus from the small island of Laut, north of Bunguran, Natuna islands group; carimatae from Karimata Island, west of Borneo; lampensis from Lanbi Kyun (= Lampi) Island in the Mergui Archipelago; insularis from Phuket (= Junk Seylon), Ko Sirae (= Sireh) and Ko Yao Yai (= Panjang) islands; and lancavensis from Langkawi Island. Sixteen subspecies presently recognized.

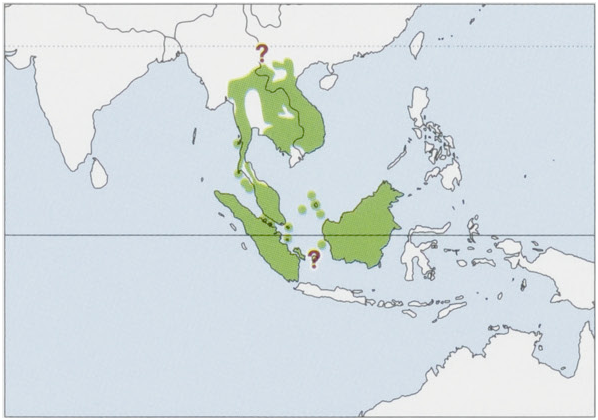

Subspecies and Distribution.

T.k.kanchilRaffles,1822—Sumatra,islandsoffESumatra(Mendol&Berhala).

T.k.abruptusChasen,1935—SubiI,oftWBorneo.

T.k.affinisGray,1861—Vietnam,Laos,SE&EThailand,Cambodia.

T.k.anambensisChasen&Kloss,1928—AnambasArchipelago(MatakI).

T.k.angustiaeKloss,1918—SMyanmar,SWThaimainland(probablylimitedtoWoftheChaoPhrayaRiver).

T.k.everettiBonhote,1903—NatunaIs(Bunguran),offWBorneo.

T.k.fulviventerGray,1836—SMalayPeninsula(Sof7°N).

T.k.hosetBonhote,1903—Borneo(Sarawak,West,Central,East&SouthKalimantan).

T.k.klossiChasen,1935—NBorneo(NEastKalimantan,E&CSabah,andpossiblyWSabahandBrunei.

T.k.luteicollisLyon,1906—BangkaI,offESumatra.

T.k.pidonisChasen,1940—KohPipidonI(=PhiPhiDon),offWMalayPeninsula.

T.k.ravulusMiller,1903—islandsoffWMalayPeninsula(KohAdang&KohRawi).

T.k.ravusMiller,1902—SThailand,NMalayPeninsula.

T.k.rubeusMiller,1903—RiauArchipelago(BintanI).

T.k.siantanicusChasen&Kloss,1928—AnambasArchipelago(SiantanI).

T. k. subrufus Miller, 1903 — Lingga Archipelago (Lingga & Singkep Is).

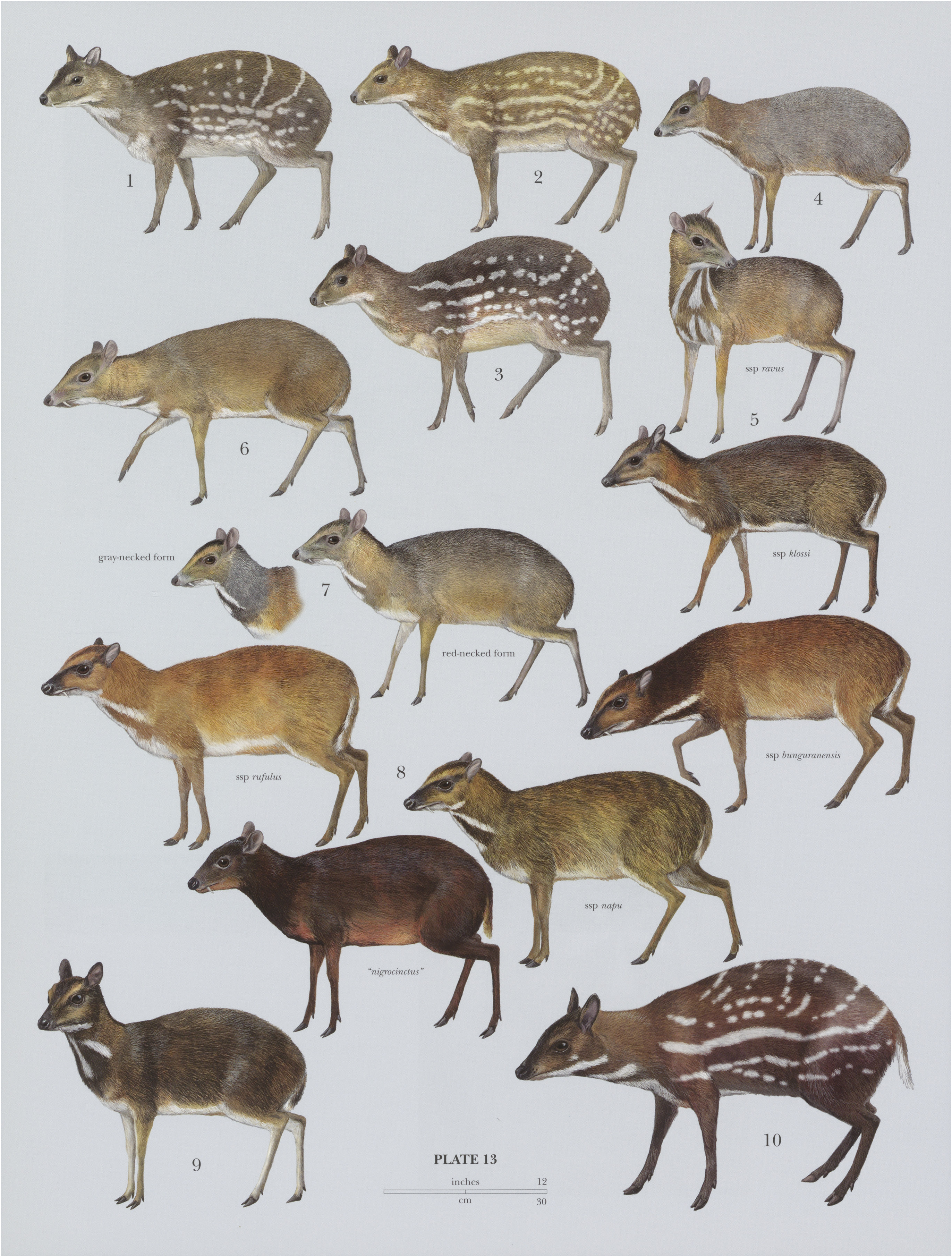

The range on the Asian mainland is poorly known and could occur as far north as China (S Yunnan). As stated in the Taxonomy section, the subspecific status of the populations of some areas of Borneo (W Sabah, Brunei & N Sarawak) and several other islands remains unclear. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head—body 37-56 cm, tail 6-9 cm; weight 1.5-2. 5 kg. Thisis a small chevrotain species that was recently split from 7. javanicus . It is separated from the larger 1. napu primarily by its smaller size, the number of throat stripes, the visibility of the nape line, and the lack of mottling of the upperparts. There is some degree of melanism in 7. kanchil specimens from small islands, leading to the development of extra dark, transverse lines, which makes the throat pattern hard to distinguish from that of 1. napu . The degree of erythrism (reddish pigmentation) and melanism is, however, less pronounced than in 7. napu . Dental formulais10/3,C1/1,P 3/3, M 3/3 (x2)= 34.

Habitat. Tall forest in lowlands, amidst undergrowth on edges of heavy lowland forest. It has been suggested that 7. kanchil occurs primarily in hilly areas, but other sources stated that the species was absent from areas above 250 m in Sarawak, whereas 7. napu occurred much higher. This species also occurs in cultivated areas up to 600 m in elevation. The habitat of this species could be described as a mosaic ofriverine, seasonal swamp and dry undulating country, vegetated predominantly by legumes and dipterocarps, with stands of dense bamboo or palms for daytime resting. In Sabah, they also inhabit mangrove forest, and they can be quite common in monocultural tree plantations in a matrix of secondary forest stands. Even though the evidence is somewhat ambiguous,it appears that this species prefers disturbed forests to primary ones. A review of encounter rates in various parts of the species’ range suggested that the distribution of 7. kanchil is perhaps highly patchy and correlated to specific habitat features and microhabitats. What these features are remains unresolved, but their water requirements are important, as authors note commonness in riverine areas with surprising regularity. The habitat use of this species with respect to edge—interior areas shows startling heterogeneity, at least in non-Sundaic areas, but this cannot yet be explained; in particular, disentangling the contributions of intrinsic habitat suitability and the effects of hunting is difficult.

Food and Feeding. The speciesis largely frugivorous, but also feeds on shoots, young leaves, and fallen fruits. Fruit mass of consumed fruits varied from 1 g to 5 g and seed mass from 0-01 g to 0-5 g. On Borneo, the species feeds on a range offruiting species, including Polyanthia sumatrana, Diospyros macrophylla, Endospermum peltatum, Quercus sp., Garcinia forbesi and G. parviflora, Litsea caulocarpa and L. orocola, Notaphoebe sp., Dialum imdum, Aglaia sp., Chisocheton sp., Dysoxylum sp., Lansium sp., Artocarpus dadah, Ficus spp., Dimocarpus longan, Paranephelium xestophyllum, and Microros antidesmifolia.

Breeding. Males mark their territories and their females with an intermandibular scent gland located under the chin. They chase and fight one another for prolonged periods, slashing with the elongated canine teeth. These teeth are razor sharp and local hunters in Borneo report that sometimes males fight to the death. Mating occurs throughout the year in some areas. In Vietnam the species mates in November-December and gives birth in April-May. The species is polygynous. Females are almost continuously pregnant. Gestation has been estimated at 140-177 days, the mother produces 2-3 young per year, and fawns are kept hidden.

Activity patterns. Diurnal to cathemeral.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. A study of this species in the Malaysian state of Sabah suggested thatit is mostly solitary, with 93-9% of the observations being single animals and the remainder pairs or a female with one or two young. In apparent contrast with this statement, camera trap photos of the species often show two adult animals together. Further studies are needed to determine the social organization of the species and how this varies spatially as well temporally. Population densities on Borneo were estimated at 21-39 ind/km?, with density positively correlated with fruit mass, seed mass, and total fruit resources. The species does not appearto be territorial. The core areas of neighboring animals were completely separate among same-sex individuals, but overlapped widely among opposite-sex individuals. The results suggest that this species is mostly monogamous, although apparently males can also be polygamous. The core area of a paired female overlapped not only with the core area of the paired male, but also with that of another neighboring male. This suggests that males tolerate the presence of females in their core areas and that paired males do not control the movement of paired females into the home ranges of other males. Females establish new home ranges when giving birth. Home range size for females was estimated at 4-4 ha and for males 5-9 ha using the minimum convex polygon method, but the differ ence between males and females was not significant. Mean daily distance travelled for males was 519-1 m (+ 88-8 m), that for females 573-8 m (+ 219-7 m). In a Bornean study area, the density was negatively correlated with pioneer trees, grass, and herbs, suggesting that the species is negatively influenced by the effects of timber harvest, although, as pointed at above, this remains ambiguous. Data from Indochina, suggest that the species is quite tolerant of forest disturbance and may even be considered an edge species that benefits from disturbance. Further studies are needed to elucidate this issue.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List, because it remains widespread and locally common, and at least in non-Sundaic areas persists in environments of very heavy forest degradation, fragmentation, and hunting. The presumed short generation length of the species (under five years) also influences assessment. Thus although there may be or may have been drastic local reductions, these have probably not been synchronous over a large enough area. The IUCN review points out several major uncertainties in the conservation status assessment. Firstly, there are few modern records of Tragulus from both the Sundaic and non-Sundaic portions of the range that have been identified conclusively as to species. Secondly, the conflicting nature of the information available concerning the effects of hunting (harvest levels are locally very high) and habitat destruction makes it difficult to estimate population declines. Thirdly, there are strong indications that in its non-Sundaic range (i.e. Asian mainland) it is localized in occurrence, a pattern for which the reasons remain opaque, but which might be the result of hunting. And fourthly, the apparent restriction to lowland forest, at least in Borneo, suggests that with the rapidly dwindling lowland forests in this part ofits range, the species is losing habitat and its range might decrease and become fragmented. The species apparently has become extinct in Bangladesh due to high hunting and trapping pressure, although in many other areas it seems to survive despite local poaching and trapping.

Bibliography. Caldecott (1988), Davison (1980), Duckworth (1997), Duckworth & Timmins (2008), Endo (2004), Heydon (1994), Heydon & Bulloh (1997), Kim et al. (2004), Liat (1973), Matsubayashi & Sukor (2005), Matsubayashi et al. (2003, 2006), Medway (1978), Meijaard (2003), Meijaard & Groves (2004a, 2004b), Meijaard et al. (2005), Miura & Idris (1999), Nolan et al. (1995), O'Brien et al. (2003), Payne et al. (1985).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Ruminantia |

|

InfraOrder |

Tragulina |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Tragulus kanchil

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2011 |

Moschus kanchil

| Raffles 1822 |