Moschus leucogaster, Hodgson, 1839

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5720521 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5720541 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C6E250-FFB9-F058-FF7B-F5D01AA9FDEB |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Moschus leucogaster |

| status |

|

3. View On

Himalayan Musk-deer

Moschus leucogaster View in CoL

French: Porte-musc de |I'Himalaya / German: Himalaya-Moschustier / Spanish: Ciervo almizclero himalayo

Taxonomy. Moschus leucogaster Hodgson, 1839 View in CoL ,

“Cis and Trans Hemelayan regions.” Probably from the Himalayan slopes of Nepal.

The similarity between Himalayan ( M. leucogaster ) and Alpine (M. chrysogaster ) Musk-deers has often led to them being confused and regarded as conspecific. At present, no subspecies are recognized, but there does appear to be geographical variation, or possibly the species should even be split into two or more distinct species.

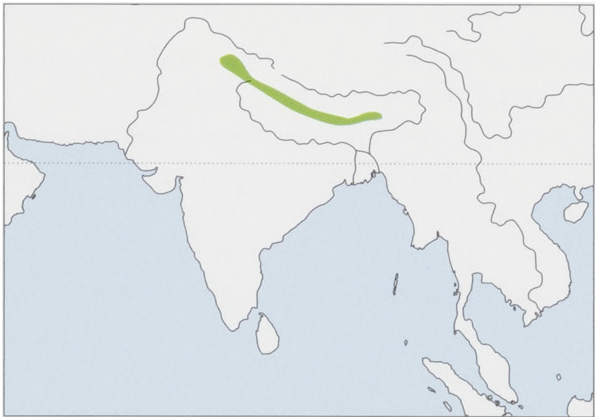

Distribution. Known from the southern slopes of Himalayas in N India (including Sikkim), Nepal, and Bhutan. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 86-100 cm,tail 4-6 cm; weight 13-18 kg. A large muskdeer; skull length is 15.3-16 cm. In the typical form ofthis species, from western Nepal, the upperparts are brownish-yellow, weaklystriated; the head gray-brown; the ears brown with grayish-white rims, and gray-white inside; some individuals have a faint grayish eye ring. The legs and rump are dark. Bases of the dorsal hairs are pure white. There is no neck-stripe; the throatis all dark. The interramal region is grayish-white, as is the underside, from chest to groin. Juveniles are clearly spotted. The facial skeleton is somewhat elongated; the lacrimal is longer than it is high, similar to the Alpine Musk-deer. There is a different looking form of this musk-deer, either a separate subspecies (or even a different species?) from Zhangmu ( 28° N, 87° E) in the forest zone of southern Tibet (Xizang): it is dark, without hair-banding, but the bases of the hairs are still white; the ears, limbs, and neck are all dark; the posterior aspect of the rump is orange-white; and the skull differs in having the nasal bones anteriorly expanded. In the Khumjung area in Nepal there is another type of musk-deer related to this species. In this population, known only from a few specimens collected on one of the Everest expeditions, the neck is somewhat paler; the throatis pale with a poorly marked stripe on either side; the chin and interramal region are creamy white; the ears are gray basally, black terminally; the buttocks are yellow-brown; the legs are mostly black; the chest is black, and the belly is more grayish. The skull also differs somewhat from M. leucogaster . There is a third unnamed form, related to this species, known from Kulu district and elsewhere in north Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, at 3000 m or more, and from neighboring regions of Nepal; this, which has been called the “pepper-and-salt” form, is brown or red-agouti, sometimes forming a “saddle.” There is often pale spotting; the throatis pale brown, with a pair of pale gray or whitish stripes along either side from the throat to the insides of the forelegs; the lower limbs are paler than the body because of white speckling; the buttocks and tail are paler; the ears are dark gray or brown with a whitish border, and white inside. Hair bases are yellow; the tips of the hairs are dark brown, and there is a white or orange bandjust below the tips. The belly is brown, paler than the rest of the body; the head is gray, flecked with white, and there are orange patches above and below the eyes. The skull is unknown. It is ironic that the only field study of a Himalayan Musk-deer was made in the Kedarnath Wild Life Sanctuary in the Garhwal region, Uttarakhand, and applies to this unnamed “pepper-and-salt” form, which may be distinct and not referable to M. leucogaster at all. In other words, it may be that along the Himalayas there is in fact a series of different species, rather than just a single species.

Habitat. Himalayan Musk-deer of this species or species-group inhabit the evergreen oak and birch forests of the Himalayan slopes of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Nepal as far east as the lower slopes of Mount Everest, between 3000 m and 4300 m. In Sikkim, where the treeline is higher because of the more evenly humid climate, they live between 2500 m and 4400 m; in Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh, the habitat 1s between 2600 m and 3000 m in thick bamboo forest. In Kedarnath, musk-deer tend to be in the open pastures on northern slopes at night. These slopes are warmer, more sheltered, and less exposed during the night. They are found on warmer, more sunny southern slopes during the day, when they rest more in shrub cover. The preferred slope angle is 30—-40°.

Food and Feeding. Diet in winter consists 39% of leaves of trees and shrubs (half of this being Rhododendron), 16% forbs (half of this being Senecio), 7% grasses, 2% ferns, 15% moss, and 21% lichen. In spring and summer, the diet consists mostly of forbs and lichen; it is mostly forbs and leaves in autumn. This contrasts with the Siberian Muskdeer, whose diet is so heavily composed oflichen.

Breeding. Latrines are most frequently used during the autumn rut. The milky-yellow musk, which is produced most strongly between May and July, may be conveyed in the urine of males, and stains it pink or red because it mixes with slough from the inner wall of the sac. Pasting on stems by the caudal gland occurs throughout the winter range, especially during the rut. Gestation length is 196-198 days; the newborn weigh 600 g. The twinning rate of only one in six births seems lower than other species, except perhaps the Alpine Musk-deer.

Activity patterns. Overall, 41% of the time is spent active, mainly at night, 59% resting, mainly by day. They are relatively silent, but hiss when alarmed; they squeal when captured or attacked by a predator. Males make a metallic rustling noise, probably by tooth grinding, in aggressive interactions. There is a contact bleat of the young to its mother. Stotting, like a gazelle,is frequent during vigilance behavior. Females seem to be more wary than males, and often flee for up to 100 m before stopping and looking back; males have a shorter median flight distance, but they hiss less and tend to look back more when fleeing. In males, the flight distance seems to be greater ( 30 m) in autumn, in the rut, than in winter and spring, when it is only 15-20 m.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Scent marking includes defecation at latrines by both sexes, and secretion of musk and pasting with the caudal gland by males. Latrines occur throughout the home range and are most frequently used during the autumn rut—and perhaps not used at all in summer. In autumn, these musk-deer seem often to cover the feces with debris (earth, old pellets, and leaflitter), probably helping to keep them moist and smelly; the amount of droppingsis greater in covered than in uncovered latrines. Both sexes make them, but a male’s winter range has about 40 latrines, whereas the winter range of one female had only 23. Some latrines seem to be used exclusively by one individual, others by more than one, probably corresponding with the degree of overlap between two animals’ home ranges. Latrines may also be visitedjust to inspect them, without using them, and they can be located even when covered in snow. Both sexes scrape with the forefeet before and after defecation, but the feces are then covered, so they are not trodden underfoot and do not act to mark trails. The density varies from 3-4 ind/km? in Kedarnath up to 5-6 ind/km? in Sagarmatha National Park, Nepal, where there is more food available in winter because there is less snow. The home range of a two-year-old male in Kedarnath was 15 ha, whereas that of an older male was twice as large, 31-6 ha; an adult female occupied 26-8 ha, comparable to the adult male. Males act territorially, defending their borders by fighting.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List, because of a population decline estimated to be more than 50% over the last three generations inferred from overexploitation, which is characteristic of the genus. The species has a relatively restricted range, so its population is unlikely to be large, even if there is only one species ofthis group. According to Michael Green, the potential habitat on the south side of the Himalayas could support about 200,000 musk-deer, but the population in the 1980s was probably only about 30,000, and at least 4000 adult males were killed each year. The current status is unknown.

Bibliography. Green (1985, 1986, 1987), Groves et al. (1995), Grubb (1982).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.