Rhinichthys gabrielino, Moyle & Buckmaster & Su, 2023

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5249.5.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F146B808-9D5B-477F-9E73-09A8DFDBFA31 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7704115 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D1EC51-DE1D-FF88-3FFF-F9B7CEB3FBF4 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Rhinichthys gabrielino |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Rhinichthys gabrielino , new species, Santa Ana Speckled Dace

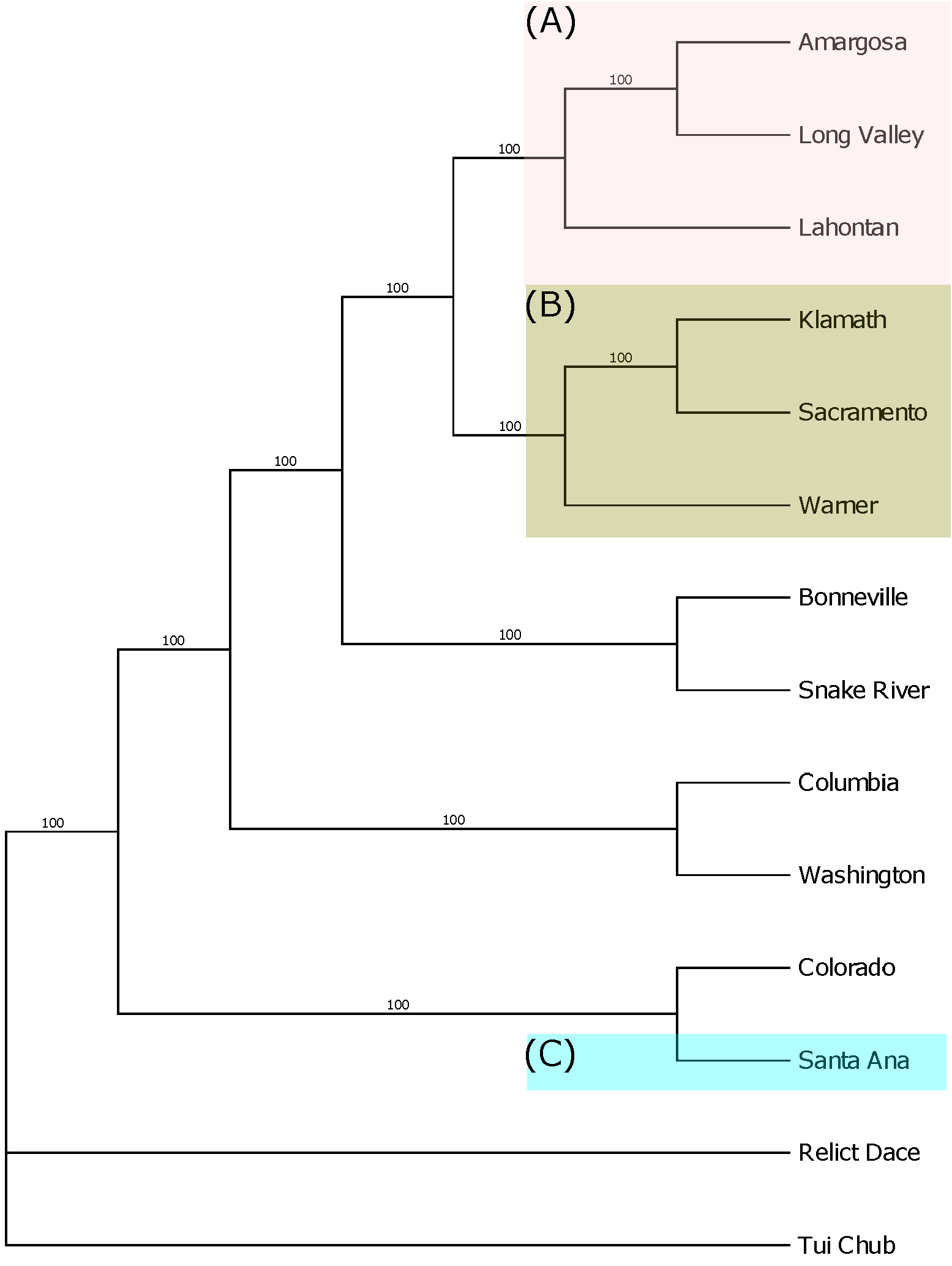

Figs. 3 View FIGURE 3 , 4a View FIGURE 4 , 5 View FIGURE 5

Synonymy. Agosia nubila carringtoni Jordan and Evermann 1896:312; Culver and Hubbs 1917:82; Rhinichthys osculus carringtoni Shapovalov and Dill 1950:386 ; Shapovalov, Dill, and Cordone 1959; Kimsey and Fisk 1960:469; Cornelius 1969:1; Oakey et al. 2004:212; R. osculus subsp. widely used in California since the 1950s (for example: Moyle 2002, Moyle et al. 2015).

Holotype. WFB 3498 ( Fig. 4a View FIGURE 4 ), 73 mm SL, East Fork San Gabriel River , South of Upper Monroe Road , Angeles National Forest , Los Angeles County, California, 34 14’ 15.85”N 117 49’ 14.58”W, USA, 2 July 2021, J. Pareti (California Department of Fish and Wildlife). GoogleMaps

Paratypes. WFB 3499–3500, WFB 3501–3507 (n =9). Same data as holotype.

Meristics: holotype ( paratypes):

Lengths(mm): standard 73(45–78), fork 82 (54–84), total 89 (57–90)

Lateral line scales: 73(69–75). Lateral line complete on all fish, although there were 1–3 scale rows beyond the end of the lateral line (counted).

Scales above lateral line 13(12–14).

Scales below lateral line (10 (8–11)

Dorsal-fin rays 7(7)

Anal-fin rays 6(6)

Pectoral-fin rays 11 (10–12)

Pelvic 6 (6–7)

Caudal-fin rays 19(19), 10 upper rays, 9 lower rays

Diagnosis. Separated from all other Speckled Dace by the absence of supraorbital bones (vs. present, Smith et al. 2017). A cryptic species otherwise not distinguishable from other species/subspecies of the Speckled Dace complex except through genomics and geography. Slightly higher lateral line scale counts (mean 74, mode 76, range 64–82) than Sacramento Speckled Dace (mean 70, mode 72, range 54–82) and Lahontan Speckled Dace (mean 68, mode 72, range 60–77) ( Table 2 View TABLE 2 ).

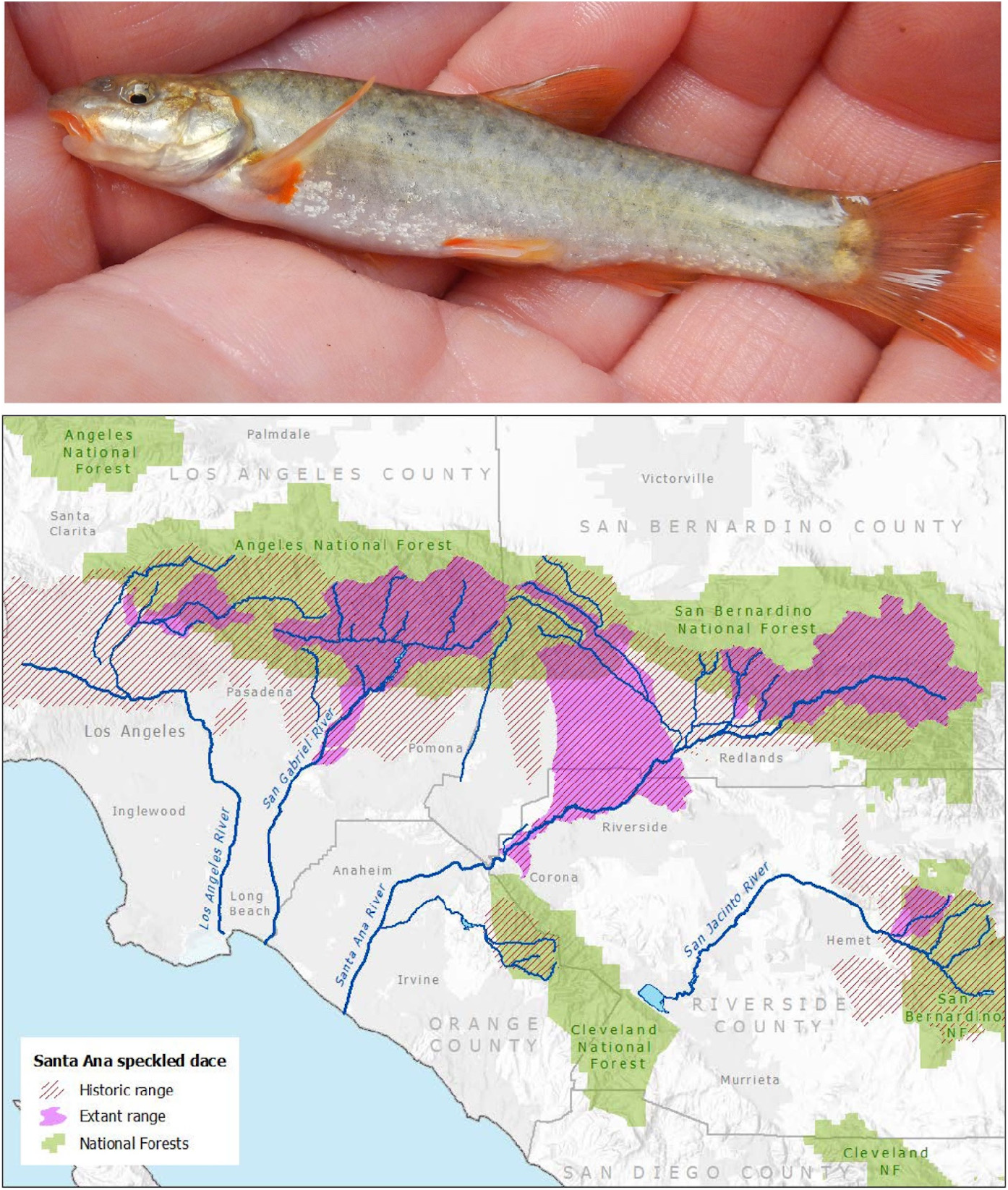

Description. A cryptic species, as shown by genomic analyses; endemic to streams of Los Angeles, San Gabriel, and Santa Ana watersheds in southern California. Recognizable by typical stocky morphology of all Rhinichthys species; small size (adults 6–11 cm SL), wide caudal peduncle (about 1/3 the body depth), blunt-pointed snout, and subterminal mouth. Meristics overlap all other Speckled Dace taxa ( Table 2 View TABLE 2 ). Body color variable, but adult fish usually pale yellow/white to dusky olive, often with small black spots. Head stripe and lateral spots/blotches pale or absent. Breeding adults of both sexes with orange to red fins; males also with red snouts and lips ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ). Lateral line usually complete, although last 1–10 scales may lack pores. High overlap in meristic counts with other California Speckled Dace populations ( Table 2 View TABLE 2 , Cornelius 1969).

Morphometrics. Cornelius (1969) compared the body and fin morphology of 491 dace using 23 truss measurements (divided by standard length or head length, with all values converted to natural logarithms). Only small differences were found between Santa Ana Speckled Dace and dace taxa from other areas. His analysis showed that Santa Ana Speckled Dace had slightly longer fins, more anterior dorsal fins, somewhat longer and narrower heads, smaller eyes, and shorter upper jaws than dace from Sacramento, Lahontan, and Colorado river basins. All differences were not statistically different. However, morphometric differences were sufficient to distinguish lineages when combined meristic measurements and measures of jaw structure (below). Thus, Santa Ana Speckled Dace could be distinguished statistically from nearby Sacramento Basin populations and from Speckled Dace from Lake Tahoe (Lahontan Basin), although overlapping morphometrics made it difficult to assign individuals to any one taxon.

Cornelius (1969:26) found that mouth structure provided the strongest separation of the taxa; he used a unique measure of jaw angle: “The lateral angle of the upper jaw formed by the premaxillary and maxillary as measured from photographs of the left side of the head.” Presumably a larger jaw angle is a measure of increased gape and size of prey. Cornelius (1969) found that Santa Ana Speckled Dace had a mean jaw angle of 145 degrees (n = 34, range 128–148) while the Sacramento dace had a mean jaw angle of 160 degrees (n=44, range 146–172). He also found that a frenum is fully developed in 54% (n=277) of the Santa Ana Speckled Dace but in only 2% (n =180) of Sacramento dace. Most (8 of 11 fish examined) Colorado Basin fish had a well-developed frenum. It was absent from (n=41) in Lahontan (Lake Tahoe) dace. Maxillary barbels were present on one or both sides of the mouth in all four dace populations compared, but they were variable in number and size so not useful for distinguishing Santa Ana Speckled Dace. Overall, Cornelius (1969) found that jaw angle, combined with other less quantitative features of the jaw, supported his finding that the Santa Ana Speckled Dace was distinct from dace from Lahontan and Sacramento basins. In combination with other features, jaw structure indicated that Santa Ana Speckled Dace had a common ancestry with fishes from the Colorado River watershed (Virgin River) ( Cornelius 1969). This conclusion is supported by genetic and genomic studies ( Smith et al. 2002, 2017, Su et al. in 2022).

Genomics/Genetics. Genetic studies (mostly using mtDNA) generally indicate that the Santa Ana Speckled Dace is a sister lineage to Speckled Dace populations in the Colorado River Basin as result of a split in lineages approximately 3.6 million years ago (mya) ( Oakey et al. 2004, Smith and Dowling 2008). Smith and Dowling (2008), using mtDNA well as morphometrics and meristics, indicate that populations of Speckled Dace in Los Angeles region streams have been isolated long enough (through the Pleistocene) to have diverged from one another and developed some small differences in morphological characters, supporting the findings of Cornelius (1969). The mtDNA analysis by Smith et al. (2017:77) showed “extreme molecular divergence” (about 7%) from other Speckled Dace populations, the highest they encountered. Oakey et al. (2004) also determined that Speckled Dace from the Santa Ana and San Gabriel rivers formed a distinct, monophyletic lineage. Su et al. (2022), using genomic data, confirmed that the Santa Ana Speckled Dace is a sister lineage to dace in the Colorado River Basin. In short, Santa Ana Speckled Dace are quite different genetically from Speckled Dace of other lineages in California and elsewhere ( Smith et al. 2017, Su et al. 2022), supporting their designation as a full species ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 ).

Distribution. Santa Ana Speckled Dace are endemic to three streams, and their tributaries, of the Los Angeles Region in southern California: the Los Angeles, San Gabriel, and Santa Ana rivers. In addition, the San Jacinto River is often treated as a separate river system. However, it historically flowed into the Santa Ana River, a connection severed by dams except in exceptionally wet years. The three river’s headwaters are in the Transverse Mountain Ranges, specifically the San Bernadino, San Gabriel, and Santa Ana mountains. The rivers flowed into an alluvial plain, now covered with Orange County development. During wet years, before the present era, this region would have flooded, connecting the Speckled Dace populations of the rivers. Today the scattered populations of Speckled Dace are largely confined to streams in a band of habitat on public lands that is below the high gradient upper regions of the three watersheds and above the developed alluvial plain. Santa Ana Speckled Dace are absent from many parts of their historic range ( Moyle et al. 2015, O’Brien et al. 2011). Each population fragment is increasingly isolated from other populations as the result of dams and other modern infrastructure.

Note: Biogeography. There is debate over exactly how the ancestors of Santa Ana Speckled Dace managed to move from the ancestral Colorado River basin to the Los Angeles region ( Minckley et al. 1986; Spencer et al. 2008, Smith et al. 2017). They had to survive in a region with a dynamic geology to do so. To colonize coastal California, the dace would have had to travel several hundred kilometers overland (in the modern landscape) over an extended period of time. Speckled Dace in general are freshwater dispersers ( Moyle and Cech 2004) so cannot move though marine environments to colonize new areas ( Moyle 2002). The dispersal route also has to accommodate two sympatric freshwater dispersers, Santa Ana Sucker ( Pantosteus santaanae ) and Arroyo Chub ( Gila orcutti ), both which share ancestry with fishes in the Colorado Basin ( Unmack et al. 2014). Smith et al. (2017) argue the fish were able to gradually make their way to California via successive stream captures in a geologically active landscape. This allowed fish to move between headwaters, eventually reaching streams that flowed into the Pacific Ocean from the Coast Range (Santa Monica Mountains). The exact route has been largely erased by the active geology. In contrast, Spencer et al. (2008) present evidence that a likely route was through a combination of two dispersal methods: movement of a plate carrying the fishes followed by colonization via headwater capture.

It is likely that dace and other fishes were ultimately moved into the vicinity of the coastal drainages through a combination of the methods proposed by Smith et al. (2017) in concert with the periodic shifting of the main channel of the Lower Colorado River. This channel migration was a dynamic process driven by sediment deposition in the Colorado River channels. Fish presumably followed the river into new channels, including those adjacent to the proto-Santa Ana River and other coastal drainages. The channel migrations eventually blocked the Colorado River, diverting its flow into a large Pleistocene/Holocene lake basin (Lake Cahuilla) subsequent to the formation of the Salton Trough (ca. 1.3 mya). This lake, a predecessor of the Salton Sea, was colonized by lower Colorado River fishes. Bones of the larger fish species have been found in middens of fishing villages along Lake Cahuilla ( Wilke 1980). Today, the Lower Colorado River and the Salton Trough are separated from the Santa Ana Basin by the 8–km-high San Jacinto and San Gorgonio Ranges. These ranges are parts of the Peninsula Range and were likely formed by complex plate movements associated with the development a bend in the San Andreas Fault System (ca. 1.1–1.5 mya) ( Spencer et al. 2008, Fattaruso et al. 2016).

The geologic movements transformed low-relief upland habitat into the dramatic landscape of today. The uplift of the ranges is associated with their westward tilting, resulting in the progressive capture and redirection of eastward-flowing tributaries at a rate of 20–44 km /my ( Dorsey and Roering 2006), presumably with the fish. The rapid vertical motions driving these events were dramatic – sometimes exceeding 10m at one time ( McClay and Bonora 2001). The suddenness of this redirection of western Colorado River tributaries into coastal-draining basins likely allowed the transfer of freshwater-dispersing fishes into the basin. These fishes apparently became completely isolated no later than ~1.1 mya ( Fattaruso et al. 2016, Smith et al. 2017) when uplift of the mountains and downfaulting of the trough created an insurmountable barrier to further dispersal. The uplift the in the Peninsula Ranges (about 1.1–1.5 mya, Fattaruso et al. 2016) created a formidable barrier to freshwater fish dispersal and can be treated as the last point in time that dace could have colonized coastal waters. It is possible that dace were isolated slightly before the San Andreas fault began to shift, as suggested by previous studies ( i.e. Spencer et al. 2008), but it is highly unlikely that isolation occurred subsequent to onset of the formation of the Salton Sink ( ca. 1.1–1.3 mya) Note: Taxonomy. This study confirms that Santa Ana Speckled Dace is a full species, using the following lines of evidence.

Taxonomy: While lacking formal description until now, the Santa Ana Speckled Dace has long been recognized as distinct ( Swift et al 1993, Moyle 1976, 2002, Oakey et al. 2004). Definitive morphometric and meristic characters are largely absent. However, when combined, they can be used to distinguish Santa Ana Speckled Dace statistically from populations of other Speckled Dace species/subspecies, as well as from Colorado River Speckled Dace, indicating their long isolation ( Cornelius 1969). The apparently unique feature of complete absence of supraorbital bones further supports the species status of this dace.

Geology: Improved understanding of the dynamic geology of southern California and of the shifting channels of the Colorado River have resulted in more supportable hypotheses as to how Speckled Dace and other endemic fishes were able to colonize coastal southern California streams.

Zoogeography: The historic distribution of the species in streams of the Los Angeles region shows long separation from their ancestral population and long isolation without access to other populations that could lead to hybridization. Although Smith et al. (2017) regard hybridization as the reason R. osculus is just one species throughout its enormous range, including the Los Angeles region, hybridization has clearly not been an issue with the Santa Ana Speckled Dace, which has had no opportunities for over 1.3 million years.

Genomics/genetics. Su et al. (2022) show that the Santa Ana Speckled Dace is the most distinct genetically of all other dace populations in California, indicating a long history without gene flow from other dace populations.

Etymology. The species epithet honors the Gabrielino-Tongva people, the indigenous inhabitants of the region at the time of the Spanish invasion and who still have a significant presence (https://gabrielinotribe.org/). The original range of the Santa Ana Speckled Dace was in the streams that flowed through the band’s homeland. The tribe is also known as San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians. The common name, Santa Ana Speckled Dace, is widely used for this fish ( e.g. Moyle 2002); it shares its name with the Santa Ana Sucker which also occurs in the Santa Ana River and adjacent watersheds.

Note: nomenclature. The scientific name has long been a source of confusion. Jordan and Evermann (1896:312) list Agosia nubila carringtoni as having a wide distribution in the Great Basin but state “To this form we also refer provisionally specimens from Lake Tahoe and elsewhere in the Lahontan basin but also those from various coastwise localities in central and southern California, where it is abundant in clear streams and springs as far south as San Luis Obispo.” Agosia n. carringtoni consequently was applied by early workers ( e.g., Snyder 1918) to most dace populations in central and southern California including in the first paper mentioning Speckled Dace in the Los Angeles region ( Culver and Hubbs 1917). Cornelius (1969:18) summarized the history of the use of carringtoni and quoted a personal communication from Carl Hubbs that there was “no sound basis for continued use of carringtoni in reference to Santa Ana Speckled Dace.” Despite this comment, Cornelius (1969) concluded that R. osculus carringtoni was the only available scientific name. Nevertheless, carringtoni reverted, with no real discussion, to being the name for Speckled Dace found in the Bonneville basin of Utah and Idaho ( Smith et al. 2017) from whence it was originally described ( Cope 1872). The Santa Ana Speckled Dace has subsequently been referred to as just R. osculus ( e.g. Swift et al. 1993, Moyle 1976, 2002) or R. osculus subsp. (e.g., Moyle and Davis 2000, Moyle et al. 2015, Smith et al. 2017) but has resisted formal description until now.

Conservation Status. In California, Santa Ana Speckled Dace historically inhabited streams in the upland areas of the San Jacinto, Santa Ana, San Gabriel and Los Angeles rivers which were interconnected by lowelevation floodplains ( Swift et al. 1993, Moyle 2002, Moyle et al. 2015) ( Figure 5 View FIGURE 5 ). They have since disappeared from much (75%) of their range, including the middle reaches and tributaries of the Santa Ana River, most of the Los Angeles River and San Jacinto River basins ( Moyle et al. 2015, Center for Biological Diversity 2020). Their current distribution is restricted to headwater streams of the San Jacinto, Santa Ana, and San Gabriel rivers and Big Tujunga Creek (Los Angeles River drainage). In 2005, Speckled Dace were reintroduced into the North Fork of Lytle Creek; a similar introduction was made into the Middle Fork in 2007 ( Moyle et al. 2015). Both were apparently successful.Attempts to establish populations of Santa Ana Speckled Dace outside their native range were made through introductions into the Santa Clara and Cuyama rivers. Success of these populations is uncertain. An additional introduction into River Springs, Mono County, failed

The third edition of the Fish Species of Special Concern Report of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife ( Moyle et al. 2015) rates the Santa Ana Speckled Dace as one of the most endangered fish in California. The report notes that the Santa Ana Speckled Dace is a U.S. Forest Service Sensitive Species in the three national forests in which it is found (Angeles, San Bernardino, Cleveland NFs). However, it is likely extirpated from Cleveland National Forest (Santiago Creek). The California Natural Diversity Database ranks Speckled Dace as secure at the global scale (G5) but the Santa Ana subspecies as Imperiled (T1S1; www.natureserve.org). It is listed as Threatened by the American Fisheries Society ( Jelks et al. 2008). The habitat of this species continues to shrink due to urbanization of the Los Angeles region, resulting in fragmentation and reduction of populations. Intense human use of their streams on public lands for recreation and water supply also contributes to their decline. Extinction seems likely in the next few decades without special protection for all remaining populations ( Swift et al. 1993, Moyle 2002, Moyle et al. 2015).

Listing Santa Ana Speckled Dace as threatened or endangered under state and federal Endangered Species Acts would be a major step towards preventing extinction. It appears that lack of a formal species description has been a barrier to listing, even though recent genetic and phylogenetic studies show it to be distinct from all other Speckled Dace ( Oakey et al. 2004; Smith and Dowling 2008, Mussmann 2018, Su et al. in 2022). It could therefore be listed as a Distinct Population Segment, even without formal description. Our paper resolves whatever taxonomic uncertainty previously confounded action by regulatory authorities.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |