Eschrichtius robustus (Lilljeborg, 1861)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6599161 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6599208 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D587FD-FFC4-8C11-FF26-FAAC11BEF663 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Eschrichtius robustus |

| status |

|

Gray Whale

Eschrichtius robustus View in CoL

French: Baleine grise / German: Grauwal / Spanish: Ballena gris

Other common names: California Gray Whale, Devilfish, Hard-head, Mussel Digger, Rip Sack, Scrag Whale

Taxonomy. Balaenoptera robusta Lilljeborg, 1861 ,

“pa Grason i Roslagan,” Graso Island, Uppland, Sweden .

This species is monotypic.

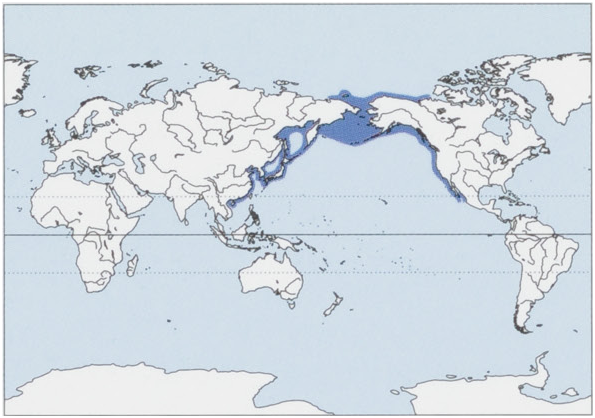

Distribution. N Pacific, from the Arctic Ocean and Bering8 Sea to Baja Y California, the Gulf of California, and portions of the mainland coast of Mexico in the E, and to the coasts of Russia, Japan, Korea, and SE China in the W. Extinct in the N Atlantic Ocean. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length 1300-1420 cm; weight 14,000-35,000 kg. There are no morphological differences among individuals of the eastern and western populations of Gray Whales. The Gray Whale is a medium-sized baleen or “mysticete” whale that can reach a maximum length of 1530 cm. Females are slightly larger than males at all ages. Distance from genitalslit to anus is wider in males; there are no othersignificant differences in external appearance between sexes. Body color ranges from mottled pale gray to dark gray with whitish to cream-colored blotches. White scars accumulate over time and add to distinctive individual color patterns. Gray Whales are heavily infested with species-specific barnacles (Cryptolepas rachianecti), and three species of cyamids or “whale lice” (Cyamus scammoni, C. ceti, and C. kessleri). Neonates are 450-500 cm long and can weigh 800 kg or more. Head is moderately arched and triangular when viewed from above and averages 20% of total length. Double nares or “blowholes,” characteristic of mysticete whales, are located on top of head just above and anterior to neck. The Gray Whale’s “blow,” or exhalation, is vertical and heart-shaped to columnar in form. Throat possesses 2-7 pleats that allow expansion of mouth cavity during feeding. Gray Whale baleen is pale yellow with ¢.130-180 individual plates, 5-40 cm long, on each side of upperjaw. Back is smooth from base of head to anterior section oftail, where instead of a dorsal fin, an elongated hump followed by a series of bumps or “knuckles” runs along dorsal edge oftailstock. Anterior flippers are paddleshaped and pointed at their tips. Flukes are butterflyshaped with pointed tips and average 300-360 cm from tip to tip. Gray Whales possess a unique “tailstock cyst” of unknown function located on the anterior ventral surface of the caudal peduncle.

Habitat. Primarily relatively shallow waters along edges of continental shelves from subtropical to polar latitudes and only occasionally open oceanic or pelagic habitats. Gray Whales frequent continental shelf waters along both sides of the North Pacific Ocean, including East China Sea, Yellow Sea, Sea of Okhotsk, Bering Sea, and Chukchi, Beaufort, and East Siberian seas in the Arctic Ocean. Gray Whales are highly migratory. When migrating, they may cross deep ocean and follow undersea mountain ranges and escarpments. In summer, they feed on the bottom of shallow continental shelves in high latitudes. In fall and spring, the western population of Gray Whalesis believed to migrate along the Pacific coast of the Far East from Russia to China. The larger eastern population migrates along the edge of the continental shelf of the Pacific coast of North America from Alaska to Mexico. In winter, Gray Whales congregate in coastal bays and lagoons that afford them protection from predation and warmer water for rearing young and mating. Their habit of frequenting relatively shallow continental shelf waters and coastal areas for feeding, migrating, and breeding is unique among mysticete whales. While capable of navigating deep ocean areas, Gray Whales migrate to and from their summer feeding and winter breeding areas along distinct corridors that follow within a few kilometers of the North American coast (for the eastern Gray Whale) and the eastern Asian coast (for some of the western Gray Whales). They disperse widely across the Arctic and polar seas during summer feeding, and they aggregate in shallow coastal areas, embayments and lagoons in subtropical latitudes for breeding and to give birth.

Food and Feeding. Primary summer feeding grounds of Gray Whales include the Gulf of Alaska, Bering Sea, Chukchi Sea, Beaufort Sea, East Siberian Sea, and Sea of Okhotsk, and they also exploit prey resources where they are found throughout their migratory distribution. They forage for patchy concentrations of prey found on relatively shallow (50 m or less) continental shelf areas that correspond with areas of high primary productivity supporting extensive benthic invertebrate communities. Gray Whales use suction feeding to exploit prey from the sea floor, but they can also feed on swimming prey by gulping and skimming prey from near the sea floor and ocean surface. Principal prey includes infaunal, tube-dwelling ampeliscid amphipods, polychaete worms, bivalves, swarming cumaceans, mysids, shrimps, krill, mobile amphipods, and shoals of clupeoid fish such as sardines and anchovies. An adult Gray Whale may consume ¢.220,800 kg of food at a rate of ¢.1200 kg/day for c.180 feeding days. Gray Whales do not feed extensively, or at all, during fall and spring migrations or while in their winter breeding areas. Fasting whales may lose up to 30% of their body fat during winter. This is especially critical for lactating females that are not feeding while nursing and caring for their offspring. Water is obtained from their food and metabolically from body fat. Warming of the Arctic Ocean due to global climate change and subsequent reduction in permanent sea ice has accelerated in recent decades and has affected distributions and availabilities of traditional prey communities. Some historical feeding areas of Gray Whales have declined in size, but it is possible that new prey communities will become established in other areas where oceanic and ice conditions are favorable. Gray Whales are responding by foraging over broader areas and staying longer in their summer feeding areas to obtain sufficient food and energy stores for winter migration and breeding. Flexibility in feeding modes and prey selection of the Gray Whale has allowed it to survive over many Pleistocene glacial and interglacial periods in the geologic past. Its abilities to use alternative prey and feeding areas are advantages for dealing with climate-driven oceanographic changes. Although switching prey has the advantage of providing additional feeding options, it may also create competition with other marine species that exploit the same resources.

Breeding. Male and female Gray Whales reached sexual maturity at 6-12 years of age. Mating and birthing are strongly seasonal and synchronized with the migratory cycle. Mating occurs during the middle of the fall southward migration and continues in January-February on the winter breeding range. Gray Whales are thought to have a “promiscuous” mating system in which females and males copulate with multiple partners. Individuals may mate in pairs and in groups of up to 20 or more whales. Mating groups are physically active and fluid, with individuals joining and leaving. Sometimes there are high-speed chases interrupted by mating bouts that last from a few minutes to hours. Males may attempt to mate with females that have newborn young, but females with young usually reject breeding males. Little overt competition has been observed among males, and multiple inseminations likely occur. Thus,it is thought that sperm competition operates in the Gray Whale instead of physical aggression to increase chances of an individual male’s fathering a young. Females invest heavily in rearing a limited number of offspring during their lifetimes, whereas males maximize their reproductive success by mating with as many females as possible. Gestation is 11-13 months, with females normally bearing one offspring at intervals of two years, but longer intervals may occur. Births occur from late December to early March, with the median in late January, when near-term females are in or near breeding grounds or migrating southward. Young are weaned and separate from their mothers at c.7-9 months of age during spring migration or on summer feeding grounds. Gray Whales are physically mature at c.40 years. The longevity record is one female killed in the 1960s who had lived as long as 80 years.

Activity patterns. Gray Whales migrate continuously day and night at 6-7 km/h, pausing only to catnap, forage, or mate. On average, swimming Gray Whales will surface every b—7 minutes between long dives and take 3-5 breaths at 15-30second intervals before submerging to resume swimming. Before beginning a long dive and after a sequence of breaths, tail flukes are frequently raised above the water’s surface. Aerial behaviors include “breaching” (jumping out of the water), “spy hopping” (raising head vertically out of the water), “tail stands” (holding flukes and tailstock vertically above water’s surface), and “lobtailing” (slapping water’s surface with flukes). Gray Whales forage continuously on their Arctic feeding grounds during long periods of daylight characteristic of these high-latitude areas in summer. During the winter breeding season, courting Gray Whales are continuously active, rarely resting at the water’s surface. In contrast, females that are nursing newborns move about breeding lagoons with their offspring and frequently rest or “sleep” at the surface while their offspring continue to swim around them and nurse. Young appear to be active at all times, never resting or sleeping.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Gray Whales in the eastern North Pacific Ocean are latitudinal migrants, engaging in an annual polar-to-subtropical migration in fall and a spring return migration to polar seas. Their round trip of 15,000-20,000 km spans 55° of latitude, and it is the longest migration of any mysticete. They exit Arctic and Bering seas from mid-Novemberto late December, following the North American coast southward to coastal Mexico and arriving there in January-February. Southward and northward migrants overlap in midwinter along the southern part of their winter range, which spans coastal waters from southern California to Mexico. Pregnant females and females with new offspring arrive in the Mexican portion of the winter range from late December to earlyJanuary, with the bulk of the population arriving by mid-February to early March. The principal winter gathering areas include Laguna Ojo de Liebre (also known as Scammon’s Lagoon), Bahia de Sebastian Vizcaino, Laguna San Ignacio, Bahia de Ballenas, and Bahia Magdalena and adjacent waters. Newly pregnant females lead the spring northward migration of eastern Gray Whales, followed by adult females and males, and then juveniles. Mothers with young are the last to leave the breeding range; they remain the longest to allow young to grow and strengthen before migrating. The western and eastern populations of Gray Whales were thought to be separate and distinct groups, but recent research indicates that they share feeding grounds along the eastern coast of Kamchatka and some western Gray Whales migrate across the Bering Sea and North Pacific Ocean and join the larger eastern population’s migration along the west coast of North America. Gray Whales from the western population have also been photographed in breeding lagoons of the eastern population. Sharing migration routes and winter breeding areas suggests that interbreeding of these two populations occurs. Incidental catches and strandings of Gray Whales offJapan support the contention that some western Gray Whales continue to migrate along the Asian coast and winter off the China coast. The fossil record suggests that eschrichtiids evolved in the Mediterranean or North Atlantic Ocean during the Miocene or earliest Pliocene, and dispersed westward into the Pacific through the then-open Central American Seaway, later dispersing back into the North Atlantic during the Pleistocene, as evidenced by subfossil remains found along the North Atlantic coasts of North America. Support for this hypothesis occurred in May 2010, when a single Gray Whale was observed off the Mediterranean coasts of Israel and Spain, and again in May 2013 when another single Gray Whale was sighted off the Namibia coast. Apparently they had migrated from the North Pacific into the Arctic Ocean, followed the northern Eurasian coast, continued along the European coast and on to the Mediterranean and the Namibia coast. Appearance of Gray Whales in the Atlantic demonstrates that such exchanges between oceans are possible during periods of interglacial minimum ice conditions. Shrinking of Arctic sea ice due to climate change suggests that Gray Whales could recolonize the North Atlantic as ice and temperature barriers to mixing between the northern North Atlantic and the North Pacific biomes are reduced. Gray Whales are not known to be social, but they do form loose aggregations on feeding grounds and during migrations. There is no evidence of social bonding other than during copulation and between mother—offspring pairs. Gray Whales disperse widely across their principal feeding areas in the Bering Sea, Chukchi Sea, and Arctic Ocean to forage for prey. Breeding males do not defend territories, show aggression toward conspecifics, or defend female “harems.” Male Gray Whales provide no parental care or assistance with rearing young. Females remain solitary when their offspring are young. They form aggregations within breeding lagoons when young are 2—4 months old. In these groups, a mother—offspring pair will cavort with other mother—offspring pairs, mixing and milling among them, perhaps socializing with each other. Females with young migrate alone rather than in groups, perhaps to minimize detection by predators.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The population in the western North Pacific Ocean is classified as Critically Endangered. The eastern population of the Gray Whale ranges from the Arctic Ocean and Bering Sea feeding grounds south along the western coast of North America to their winter aggregation and breeding areas along the Pacific coast of Baja California, the Gulf of California, and parts of the mainland coast of Mexico, numbering ¢.21,000 individuals in 2009. The western population is only ¢.120-130 individuals and feeds along the northern shores of the Sea of Okhotsk, off Sakhalin Island, and the eastern coast of Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia; their breeding areas are not certain but are believed to be off south-eastern China. Recent genetic and photographic identification studies indicate that the western and eastern populations of Gray Whales share a summer feeding ground in the western Bering Sea along the Kamchatka coast, and that some western Gray Whales migrate eastward across the Bering Sea and North Pacific in fall to join the southward migration of eastern Gray Whales and overwinter in the coastal breeding lagoons of Baja California. It is not known to what extent, if any, these two populations interbreed, and this is an active area of research. Hunting throughout their distribution reduced numbers of Gray Whales to critically low levels by the 1930s, and it received international protection from commercial whaling under the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. Two US statutes, the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act and the 1973 Endangered Species Act, provide protection within US waters. In 1994, the US Department of the Interior removed the eastern North Pacific population from the Endangered Species Act’s List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants. In 1972, Mexico protected Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Scammon’s Lagoon), and in 1979, Laguna San Ignacio became a Whale Refuge and Maritime Attraction Zone. In 1980, Mexico extended reserve status to Laguna Manuela and Laguna Guerrero Negro. All of these lagoons lie within the El Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve, created in 1988. In 1993, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization designated Ojo de Liebre and San Ignacio lagoons as World Heritage Sites, and they are also Ramsar-protected wetlands under the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance. In 2002, all Mexican territorial seas and Economic Exclusion Zones were declared a refuge to protect large whales. Gray Whales also receive varying degrees of protection in territorial waters of Canada, Russia, Japan, Korea, and China. Threats that persist throughout the distribution of the Gray Whale include entanglement in fishing gear, collisions with ships, habitat loss from oil and gas exploration, and general disturbance from coastal development.

Bibliography. Alter et al. (2007), Andrews (1914), Barnes & McLeod (1984), Bisconti (2008, 2010), Bisconti & Varola (2006), Brownell et al. (2007), Cooke et al. (2007), Dahlheim et al. (1984), Darling et al. (1998), Deméré etal. (2005), Elwen & Gridley (2013), Henderson (1972, 1984), Heyning & Mead (1997), Highsmith et al. (2006), Ichishima et al. (2006), Jones & Swartz (1984, 2009), Jones et al. (1984), Laake et al. (2009), Mate etal. (2003), Mead & Mitchell (1984), Moore (2008), Moore et al. (2007), Nerini (1984), Norris et al. (1977), Omura (1984), Reilly (1984), Rice & Wolman (1971), Rice et al. (1984), Rychel et al. (2004), Scammon (1874), Scheinin et al. (2011), Steeman (2007), Swartz (1986), Swartz et al. (2006), Tomilin (1957), Urban et al. (2003), Weller et al. (2012), Werth (2007), Wisdom (2000).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Mysticeti |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Eschrichtius robustus

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2014 |

Balaenoptera robusta

| Lilljeborg 1861 |