Hylobates klossii (G. S. Miller, 1903)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6727957 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6728289 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D787BA-0E3A-FFC3-FFE5-F732F651C728 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Hylobates klossii |

| status |

|

Kloss’s Gibbon

French: Gibbon de Kloss / German: Kloss-Gibbon / Spanish: Gibon de Kloss

Other common names: Dwarf Gibbon, Mentawai Gibbon

Taxonomy. Symphalangus klossii G. S. Miller, 1903 ,

Indonesia, West Sumatra, South Pagai Island.

Little to no geographic variation has been observed among populations on differ ent Mentawai islands. In a very small sample of specimens, some variation in the direction of the hair on the forearm was observed. Genetic and vocal data suggest that no differentiation has occurred between the islands, likely due to historic gene flow as recently as 7000 years ago. Monotypic.

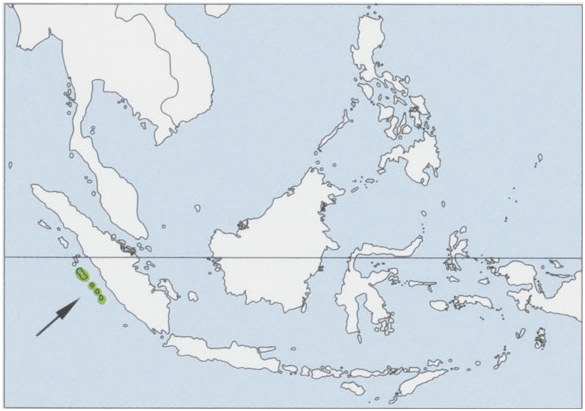

Distribution. Endemic to the MentawaiIs off the W coast of Sumatra (Siberut, Sipura, North Pagai, South Pagai, and Sinakakislet off the E coast of South Pagai). View Figure

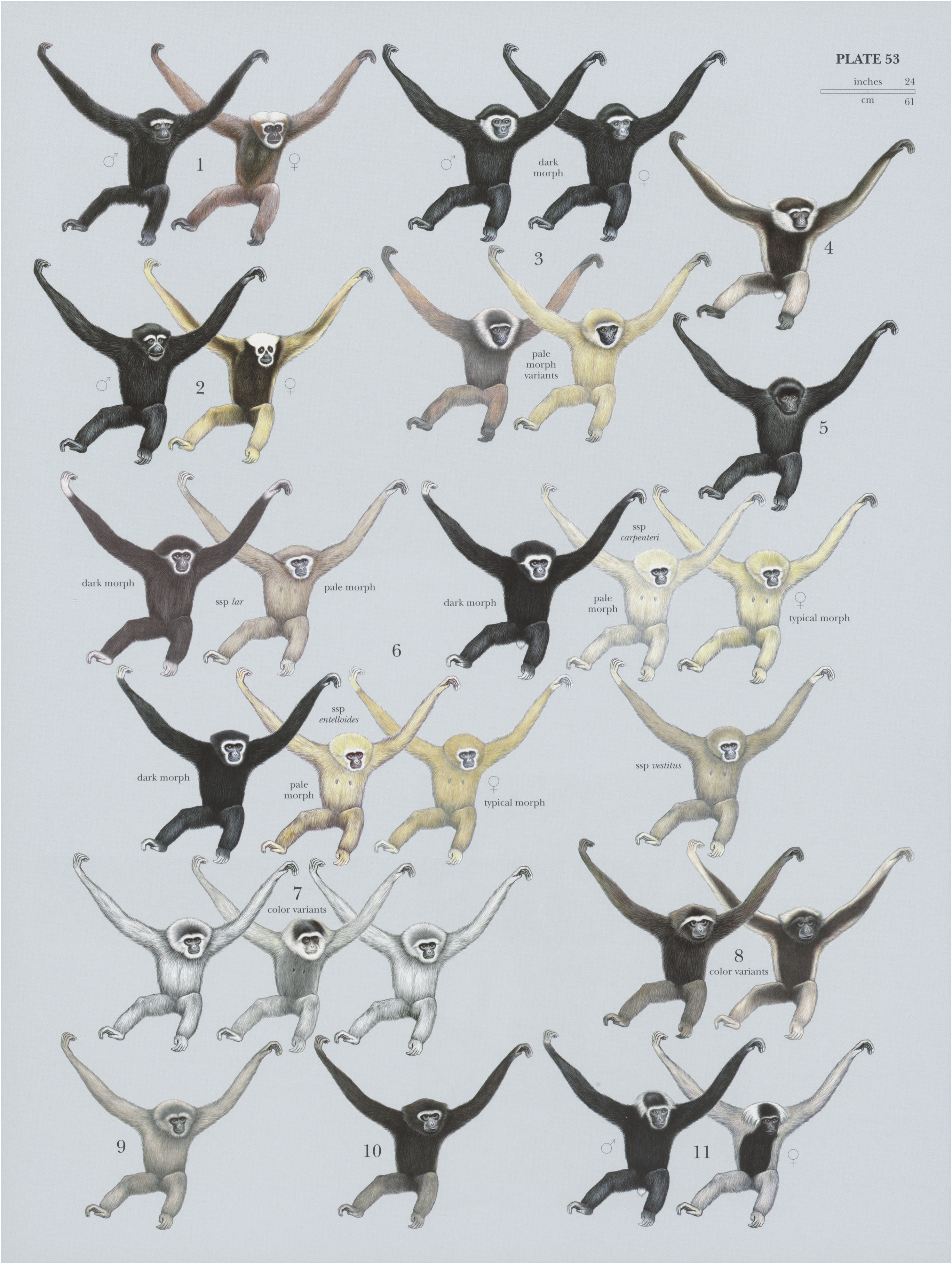

Descriptive notes. Head-body 43.5-58.5 cm (males) and 42-58 cm (females); weight 5.7-8 kg (males) and 4.4-6.8 kg (females). Female Kloss’s Gibbonsare slightly smaller than males, but they have canine teeth that are similar in size. Kloss’s Gibbon is considered one of the smallest gibbons, although its body size is within the range observed in other species of Hylobates . Both sexes and all ages have completely black fur with no markings. Kloss’s Gibbon was originally described as a “dwarf siamang” due to its black fur, but morphologically it more closely resembles other species of Hylobates than the Siamang ( Symphalangus syndactylus ). One notable difference is that the fur is sparser than is typical of other species of Hylobates , and there is a nearly bare area on the throat. In some respects, the skull of the Kloss’s Gibbon also resembles that of the Siamang.

Habitat. Primary semi-deciduous monsoon and tropical evergreen forest at all elevations. Kloss’s Gibbons generally prefer to remain in the upper canopy. They have also been observed in swamp forest. Mentawai forests are ever-wet, with annual rainfall of up to 4000 mm. Throughoutits distribution, Kloss’s Gibbon is sympatric with the Pigtailed Langur (Simias concolor ), and the Siberut Langur (Presbytis siberu) and the Siberut Macaque (Macaca siberu) on Siberut and the Mentawai Langur (P. potenziani) and the Pagai Macaque (Macaca pagensis) on the southern Mentawai Islands.

Food and Feeding. Kloss’s Gibbons are predominantly frugivorous. Fruits make up c.73% of their feeding time, arthropods and other small animals ¢.25% (their primary source of protein), and leaves c.2% (less than is typical of other gibbons). Kloss’s Gibbon is dominant to the Siberut and Mentawai surelis, always displacing them from food trees when they meet.

Breeding. Kloss’s Gibbon appears to breed throughout the year. Single births are the norm. Age classification is the same as for other gibbons: infants up to two years old are dependent on the mother;juveniles, age 2—4 years, are independent; adolescents, age 4-6 years, display increased aggression toward same-sex parents; the subadult stage begins when about six years old; and adult independence is typically achieved at about eight years old. Adult males do not carry offspring. Individuals may live more than 30 years.

Activity patterns. Kloss’s Gibbons are diurnal and arboreal. Groups spend much of their day at rest. They do not use the same sleeping tree two nights in a row and choose sleeping sites that do not have biting ants. They also prefer sleeping trees that lack hanging lianas, which may be an adaptation to avoid human predation because Mentawai hunters often climb lianas to shoot primates. Unlike most other gibbons, Kloss’s Gibbons do not sing duets. Instead, adult males sing from sleeping trees in the hours before dawn, sometimesas early as 01:00 h. Adult females typically chorus after the first feeding bout of the day (07:00-09:00 h). Singing appears to be contagious, and male bouts typically occur in “countersinging” interactions, in which adjacent individuals take turns singing and avoid overlapping. Neighboring females may produce songs in synchrony. The greatcall of the female Kloss’s Gibbon has been described as “the finest music uttered by any land mammal,” and itis often accompanied by an acrobatic display. Females exhibit structural individuality in their songs, such that each female can be distinguished by their song alone. The male’s song is simpler than the female’s. As in other gibbons, the primary function of the female's song is to defend the territory and possibly to advertise mated status. Solitary, “floating” male Kloss’s Gibbons that do not occupy a territory have been observed to sing, suggesting that mate attraction may be a function of the male’s song.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home ranges of Kloss’s Gibbons are 7-32 ha, probably varying in relation to habitat quality and floristic composition. Average daily movement is 1514 m. Group size is typically 4-6 individuals. Groups as large as 10-15 individuals have been observed on North Pagai and Siberut, butit is unclearif these are stable units. In general, males are aggressive toward other males and defend their territories from predators (humans), while females tend to lead group’s movements during the day, and also exclude other adult females from the group. At about eight years old, Kloss’s Gibbons find a mate and establish their own territory. Young adult Kloss’s Gibbons may establish territories adjacent to their parents’ territories, with their parents’ assistance. They may also replace a deceased same-sex adult in their parental territory to live with the remaining opposite-sex adult; in the observed cases,it was not known whether that surviving adult was the genetic parent of the young adult. Disturbance levels in the habitats of Kloss’s Gibbons vary on the different islands, but recent surveys have detected similar densities in unlogged forests, forests logged ten years ago, and those logged 20 years ago. The highest densities have been observed in northern Siberut. Density in the Mentawai islands averages 12 ind/km?,

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Kloss’s Gibbon is protected under Indonesian law, but it occurs in only one protected area, Siberut National Park. The total population, based on limited survey effort using auditory sampling, is 20,000-25,000 individuals, with island totals of 18,210-21,345 for Siberut, 753-880 for Sipora, and 1680-1974 on North and South Pagai together (another estimate for these last two islands, using a transect-based approach, was 2029 individuals). The vast majority of the global population is believed to be in Siberut National Park, with 13,190-15,413 individuals, but this estimate is based on a survey of less than 0-1% of the park and therefore needs to be viewed as preliminary. Total population decline of Kloss’s Gibbon may be ¢.50% since 1980. Threats include hunting, commercial logging, forest conversion for agroindustry, especially oil palm, and forest clearance and disturbance at the local scale. Selective logging is widespread across the distribution of Kloss’s Gibbon , but one study suggests that this may have limited impact on carrying capacity. Hunting pressure has been exacerbated by increased access to forested areas through logging infrastructure and a move away from traditional hunting methods in the use of guns. Infant Kloss’s Gibbons are often taken as pets by hunters after they kill a parent. Traded Kloss’s Gibbons mostly remain in the Mentawai islands but sometimes go to neighboring western Sumatra. Increased legal protection of the remaining populations, including those in the Peleonan Forest, increased commitment and planning for conservation from logging companies, and improved enforcement in Siberut National Park are key conservation interventions.

Bibliography. Chasen & Kloss (1927), Chivers (2001), Groves (2001), Haimoff & Tilson (1985), Keith et al. (2009), Marshall & Marshall (1976), Miller (1903), Nijman (2005b), Paciulli (2004), Schultz (1932), Tenaza (1974, 1975, 1976, 1987), Tenaza & Hamilton (1971), Tenaza & Tilson (1977, 1985), Tilson (1980, 1981), Tilson & Tenaza (1982), Whittaker (2005, 2006, 2009), Whittaker & Geissmann (2008), Whitten (1982a, 1982b, 1982c, 1982d, 1982¢, 1984).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.