Newportia Gervais, 1847

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4825.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F230F199-1C94-4E2E-9CE4-5F56212C015F |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4455385 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03DE092D-FFFE-D707-FF13-FE8F2992DD5E |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi (2020-12-30 15:23:09, last updated 2023-11-01 01:32:34) |

|

scientific name |

Newportia Gervais, 1847 |

| status |

|

(!) Newportia Gervais, 1847 View in CoL View at ENA

Diagnosis. As for subfamily.

Number of species. 50 species, 57 taxa of species rank (new data).

Remarks. Newportia (in various senses) treated as a genus in Edgecombe & Bonato (2011: 405), Vahtera et al. (2012a: 12, 2013: 579), Schileyko (2013: 40, 2014: 159, 2018: 61), Edgecombe et al. (2015: 65), Bonato et al. (2016), Martínez-Muñoz & Tcherva (2017: 179) and Chagas-Jr (2018: 154). The most recent morphologic accounts on Newportia (in the old sense) are those of Schileyko (2013, 2014, 2018) and Chagas-Jr (2018).

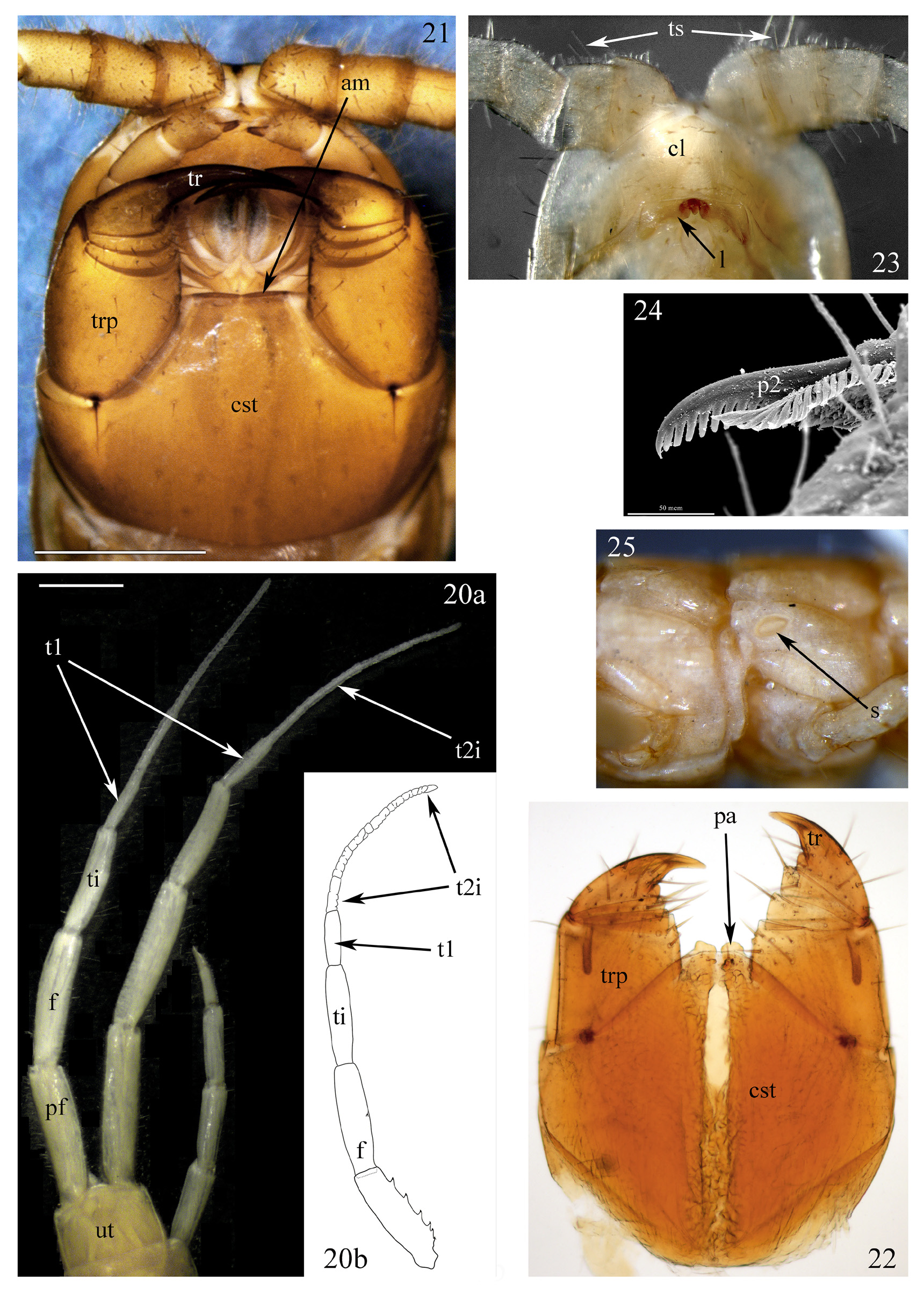

There is a longstanding question on subgeneric division of this genus. Reviewing Newportia (in the long-held sense) solely on the basis of morphology, Schileyko and Minelli (1999: 267) regarded as problematic “any identification of natural subgroups within this large genus … although, based on the structure of the terminal [= ultimate] tarsus, we practically recognize two groups of species … Newportia [( Newportia )] and Scolopendrides ”. In 2012 Edgecombe et al. wrote (p. 779): “The molecular data resolve a clade within Newportia that was ambiguous based on morphology alone, one composed of Newportia divergens , Newportia ernsti , and Newportia stolli ... This group corresponds to Scolopendrides Saussure, 1858 , formerly employed as a subgenus of Newportia … A possible apomorphy for this group is the traditional defining character of Scolopendrides , irregular boundaries between the tarsomeres of tarsus 2 of the ultimate leg”. Those data were supported by Vahtera et al. (2013: 591) who, based on combined analysis, stated that “One of the best-supported clades within Newportia is a grouping of species with irregular boundaries between tarsomeres on the ultimate leg” (p. 591) and that “A reclassification of Newportia … might also reconsider the utility of Scolopendrides because the group is unambiguously monophyletic” (p. 589). The nomenclatural validity of Scolopendrides Saussure is disputed in a forthcoming work by C. Martínez-Muñoz. Pending publication of that work, we desist from using this name but recognize the utility of taxonomically separating a group of species with the secondary articles of ultimate tarsus 2 definitely separated ( Fig. 19 View FIGURES 14–19 ) as the nominate subgenus and a group with irregularly divided ultimate tarsus 2 ( Fig. 20 View FIGURES 20–25 ).

Vahtera et al. (2013) also reclassified the genera Tidops , Ectonocryptops and Ectonocryptoides as subgenera of Newportia (see below). Taking into consideration the re-validation of the subgenus Newportides by Chagas-Jr (2018) (see below), the genus Newportia should at the moment include five subgenera.

There is also much confusion concerning the exact number of Newportia species. According to Edgecombe and Bonato (2011: 405) the genus includes “More than 50 species”, the most recent key of Schileyko (2013) contains 45 taxa of species rank, Vahtera et al. (2013: 589) mentioned “50+ species”, Edgecombe et al. (2015: 65) wrote about “some 60 nominal species or subspecies”, Bonato et al. (2016) gave 57 species, Martínez-Muñoz & Tcherva (2017: 179) gave 66 species and Chagas-Jr (2018: 154) wrote about “more than 70 taxa at species rank”. It should be noted, however, that the first two papers considered Newportia in the “old” sense (i.e. before Vahtera et al. 2013), whereas in the rest of them this genus also accommodates Tidops , Ectonocryptops and Ectonocryptoides . Moreover, the authors mentioned above (except for Schileyko 2013 and Chagas-Jr 2018), included in Newportia all 17 “new species” that were poorly defined from Venezuela by González-Sponga (1997, 2000). The corresponding type material was re-investigated by Chagas-Jr who informed A.S. (e-mail of 2014) that only three of those “species” are valid. We regard two of them ( N. avilensis and N. prima , both of González-Sponga, 1997) as members of the species-group that has previously been referred to the former Scolopendrides (= Newportia ( Newportia )) and N. cerrocopeyensis González-Sponga, 2000 , as a member of Newportia (Newportia) . In 2018 Chagas-Jr also confirmed validity of N. pilosa González-Sponga, 1997 thus only 4 of those doubtful 17 “species” should currently be valid (the corresponding paper of Chagas-Jr is in preparation; personal communication). Chagas-Jr (2018: 167) also questioned the taxonomic validity of N. sulana Chamberlin, 1922 (which has previously been synonymised with N. stolli (Pocock, 1896) by Schileyko and Minelli 1999). Only two species of Newportia were described (both by Ázara & Ferreira 2014) since publication of Schileyko’s (2013) paper; Schileyko (2018: 64) lowered the taxonomic status of N. cubana Chamberlin, 1915 to N. longitarsis cubana .

Summing up, given the species of all subgenera, the total number of species in the genus Newportia should currently be 50 (or 51, see below). And namely: 25 species of Newportia (Newportia) (plus 6 subspecies of N. longitarsis (Newport, 1845) and 2 subspecies of N. weyrauchi Chamberlin, 1955 ), 15 of the group that has previously been referred to Scolopendrides (plus 2 subspecies of N. ernsti Pocock, 1891 ) + 3 of Newportides (or 4 if N. sulana is a valid species, which we doubt) + 4 of Tidops + 1 of Ectonocryptops + 2 of Ectonocryptoides .

Bonato, L., Chagas-Junior, A., Edgecombe, G. D., Lewis, J. G. E., Minelli, A., Pereira, L. A., Shelley, R. M., Stoev, P. & Zapparoli, M. (2016) ChiloBase 2.0 - A World Catalogue of Centipedes (Chilopoda). Available from: http: // chilobase. biologia. unipd. it (accessed 2 August 2016)

Chamberlin, R. V. (1922) Centipeds of Central America. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 60 (7), 1 - 17.

De Azara, L. N. & Ferreira, R. L. (2014) Two new troglobitic Newportia (Newportia) from Brazil (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha). Zootaxa, 3881 (3), 267 - 278. https: // doi. org / 10.11646 / zootaxa. 3881.3.5

Edgecombe, G. D. & Bonato, L. (2011) Chilopoda-taxonomic overview. Order Scolopendromorpha. In: Minelli, A. (Ed.), Treatise on Zoology-Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. The Myriapoda. Vol. 1. Brill, Leiden, pp. 392 - 407.

Martinez-Munoz, C. A. & Tcherva, T. (2017) Primer registro de Newportia stolli (Pocock, 1896) (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha: Scolopocryptopidae) para Cuba y las Antillas. Boletin de la Sociedad Entomologica Aragonesa, 60, 179 - 184.

Schileyko, A. & Minelli, A. (1999) On the genus Newportia Gervais, 1847 (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha: Newportiidae). Arthropoda Selecta, 7 (4), 265 - 299.

Vahtera, V., Edgecombe, G. D. & Giribet, G. (2012 a) Evolution of blindness in scolopendromorph centipedes (Chilopoda: Scolopendromorpha): insight from an expanded sampling of molecular data. Cladistics, 28, 4 - 20. https: // doi. org / 10.1111 / j. 1096 - 0031.2011.00361. x

Vahtera, V., Edgecombe, G. D. & Giribet, G. (2013). Phylogenetics of scolopendromorph centipedes: can denser taxon sampling improve an artificial classification? Invertebrate Systematics, 27 (5), 578 - 602. https: // doi. org / 10.1071 / IS 13035

FIGURES 14–19. Ectonocryptops kraepelini Crabill, 1977; Holotype 14 figures 5, 6 of Shelley & Mercurio (2008): ultimate LBS and left ultimate leg (dorsally) + left ultimate leg (ventrally); Ectonocryptoides sandrops Schileyko, 2006; Holotype Rc 7197 15 LBS 23 + left ultimate leg dorsally; Ectonocryptoides quadrimeropus Shelley & Mercurio, 2005; AMNH, Puebla specimen of Shelley (2009) 16 Apical part of maxilla 2 laterally; Ectonocryptoides sandrops Schileyko, 2006; Holotype Rc 7197 17 Head + forcipular segment ventrally 18 General view dorso-laterally; Newportia monticola Pocock, 1890; Ad. N 7078 19a left side of ultimate LBS + ultimate legs dorso-laterally; Newportia monticola Pocock, 1890 19b right ultimate leg ventrally (schematic); (am)—anterior margin of forcipular coxosternite, (cp)—coxopleural process, (dp)—distomedial uncinate process of tibia, (p2)—pretarsus of maxilla 2, (pf)—prefemur, (ti)—tibia, (t1)—tarsus 1, (t2g)—reduced globose tarsus 2, (t2r)—tarsus 2 with regularly divided secondary articles, (ut)—ultimate tergite, (vsp)—ventral spinous process.

FIGURES 20–25. Newportia stolli (Pocock, 1896); Ad. Rc 7235 (?) 20a ultimate LBS + ultimate legs dorsally; Newportia divergens Chamberlin, 1922 20b right ultimate leg (schematic); Newportia longitarsis virginensis Lewis, 1989; Ad. Rc 7470 21 head and forcipular segment ventrally; Newportia (Tidops) collaris (Kraepelin, 1903); MCZ 32933 22 forcipular segment ventrally 23 anterior half of head ventrally 24 apical part of maxilla 2 laterally 25 right pleuron of mid body LBS laterally; (am)—anterior margin of forcipular coxosternite, (cl)—clypeus, (cst)— forcipular coxosternite, (f)—femur, (l)—labrum, (p2)—pectinate pretarsus of maxilla 2, (pa)—blunt projection of anterior margin of forcipular coxosternite, (pf)—prefemur, (s)—open spiracle with atrium, (t1)—tarsus 1, (t2i)—tarsus 2 with irregularly divided secondary articles, (th)—trichoid sensillae, (ti)—tibia, (tr)—tarsungula, (trp)—forcipular trochantero-prefemur, (ut)—ultimate tergite.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |