Saguinus ursulus Hoffmannsegg, 1807

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3721.2.4 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:ED6825F3-9730-4B7B-A445-4ADC9ECCB699 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5694013 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03E40A75-FFD7-FFE7-FF26-796D3D4C2A81 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Saguinus ursulus Hoffmannsegg, 1807 |

| status |

|

Saguinus ursulus Hoffmannsegg, 1807 View in CoL revalidated taxon

Saguinus Ursula Hoffmannsegg, 1807: 102 . Simia ursula: Humboldt, 1812: 361 .

Midas ursula : Geoffroy, 1812: 121

Jacchus ursulus: Desmarest, 1818: 242

Hapale ursulus: Voight, 1831: 99

Leontocebus ursulus: Cabrera, 1912: 29

Cercopithecus ursulus: Elliot, 1913: 192

Mystax ursulus: Pocock, 1917: 256

Tamarin tamarin : Hill, 1957: 83, part

Tamarin tamarin tamarin: Cruz-Lima, 1945: 215, part Leontocebus tamarin: Cabrera, 1958: 197 , part Saguinus tamarin tamarin: Carvalho & Toccheton, 1969: 219 Saguinus midas niger: Hershkovitz, 1969: 19 , part Saguinus niger: Groves, 2001: 138 , part

Type-series. We designate here the lectotype based on one specimen of four syntypes housed at Museum für Naturkunde. The designation was based on the analysis of photographies of the specimens.

Lectotype—Adult female, skin and skull, collected by F. W. Sieber. Specimen number ZMB_MAM 288a, in good conditions of preservation. Although with pelage slightly faded, specimen presents all diagnostic characters for S. ursulus . The designation of lectotype is necessary to bear the name “ ursulus ” and provide taxonomic stability.

Diagnosis. Dorsal striated hairs extending from scapular portions to the rump in hindlimbs; striated hairs reach the base of the tail; mid-dorsal striated hairs with bright and golden buffy intermediary band; intermediary yellow band long (5.0 5.5 mm); dorsal and lateral hairs long (23–26 mm) and irregularly arranged (disheveled); face, hands, and fingers not notably haired.

Distribution. Saguinus ursulus occurs south of the Amazonas River, from the east bank of the Tocantins River, State of Pará, to the limits of Amazon forest with Cerrado and Caatinga biomes, in the State of Maranhão ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ).

Saguinus niger is restricted here to occurs in the south of the Amazonas River, from the east bank of the Xingu River to the west bank of Tocantins River, and in the southwestern portion of Marajó Island, in State of Pará, Brazil ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ). Southernmost records of S. niger are Gradaús River, based on voucher, and Floresta Nacional de Carajás (not mapped here) based on captures and visual observations (Bergallo et al. 2012).

Taxonomic notes. The taxonomic and nomenclatural history of S. niger and S. ursulus is quite confusing and complex. Sagouin niger Geoffroy was presumably based on description of Tamarin negrè Audebert (1797): “Noir, dos nodule transversalement de fauve, pates noires” (Geoffroy 1803: 13). However, the provenience of the type was indicated as “Cayenne” what was pivotal for the confusion, because the black-hand tamarin certainly do not occur in French Guiana. Hershkovitz (1977: 717) restricted the type locality of S. niger to Belém, State of Pará, Brazil, the same type-locality of S. ursulus Hoffmannsegg (1807) . However, the type of S. niger is lost (see more explanations in Voss et al. 2001) and presently is not possible to know the precise provenience of specimen analyzed by Geoffroy (1803) or even details about its morphology (for example, if is a menalic form of S. midas — Voss et al. 2001).

Hoffmannsegg (1807: 102) described Saguinus ursulus based on material from vicinity of Belém, eastern Tocantins River, State of Pará: “ Niger , labio fisso, auribus amplis nudis subtriangularibus, dorso posteriore hypochondriisque ferrugineis maculato-virgatis”. Four syntypes, one juvenile male, two adult females and one juvenile female are housed at Zoologisches Museum Berlin (N. Lange, pers. com.). What name should be applied to black tamarin occurring in the east bank of Tocantins River for long was disputed, whether “ ursulus ” or “ niger ”; More recently S. niger was accepted (Groves, 2001, 2005, Gregorin et al. 2010, Paglia et al. 2012).

Thomas (1922) described S. umbratus from Cametá, western portion of Tocantins River, and he referred to it as a darker subspecies of Mystax (= Saguinus ) ursulus that was known to occur on the east bank of the Tocantins River: “Similar in essential characters to Pará ursulus , but darker throughout...” (Thomas 1922: 265). As mentioned, more recently the name “ ursulus ” has been abandoned and the name “ niger ” has been used to present. Saguinus ursulus umbratus was recognized as a subspecies since its description and its validity until the 1970´s (Cruz Lima 1945, Hill 1945, Carvalho 1960) when it was synonymized by Hershkovitz (1977) under S. midas niger .

Saguinus m. niger was subsequently ranked as a species (Groves 2001 and 2005, Voss et al. 2001, Rylands et al. 2012) based on morphological (Hershkovitz 1977, Natori & Hanihara 1988), cytogenetic (Nagamachi et al. 1990), biochemical and molecular evidences (Tagliaro et al. 2005, Vallinoto et al. 2006), and also due to the fact that the ranges of S. midas and S. niger are separated by the Amazonas River. The species was considered monotypic and occurring from east bank of Xingu River to Amazonian forest in State of Maranhão. Hershkovitz (1977) concluded that “The differences in the color and banding of saddle, evident in our material from east and west of the Tocantins, are too slight and broadly overlapping to merit taxonomic recognition” (p.717). Thus, the names “ ursulus ” and “ umbratus ” are presently junior synonyms of S. niger .

In order to solve the problem of type and type-locality which the name “ niger ” is bearing, Voss et al. (2001) designated a neotype (AMNH 96500) from Cametá, western bank of Tocantins River. This designation was pivotal to consider, at least, Mystax umbratus as junior synonym of S. niger . Thus, the names “ niger ” and “ umbratus ” presently refer to populations occurring on left side of Tocantins River, and “ ursulus ” is the oldest and available name to refer to the populations on east bank of Tocantins River.

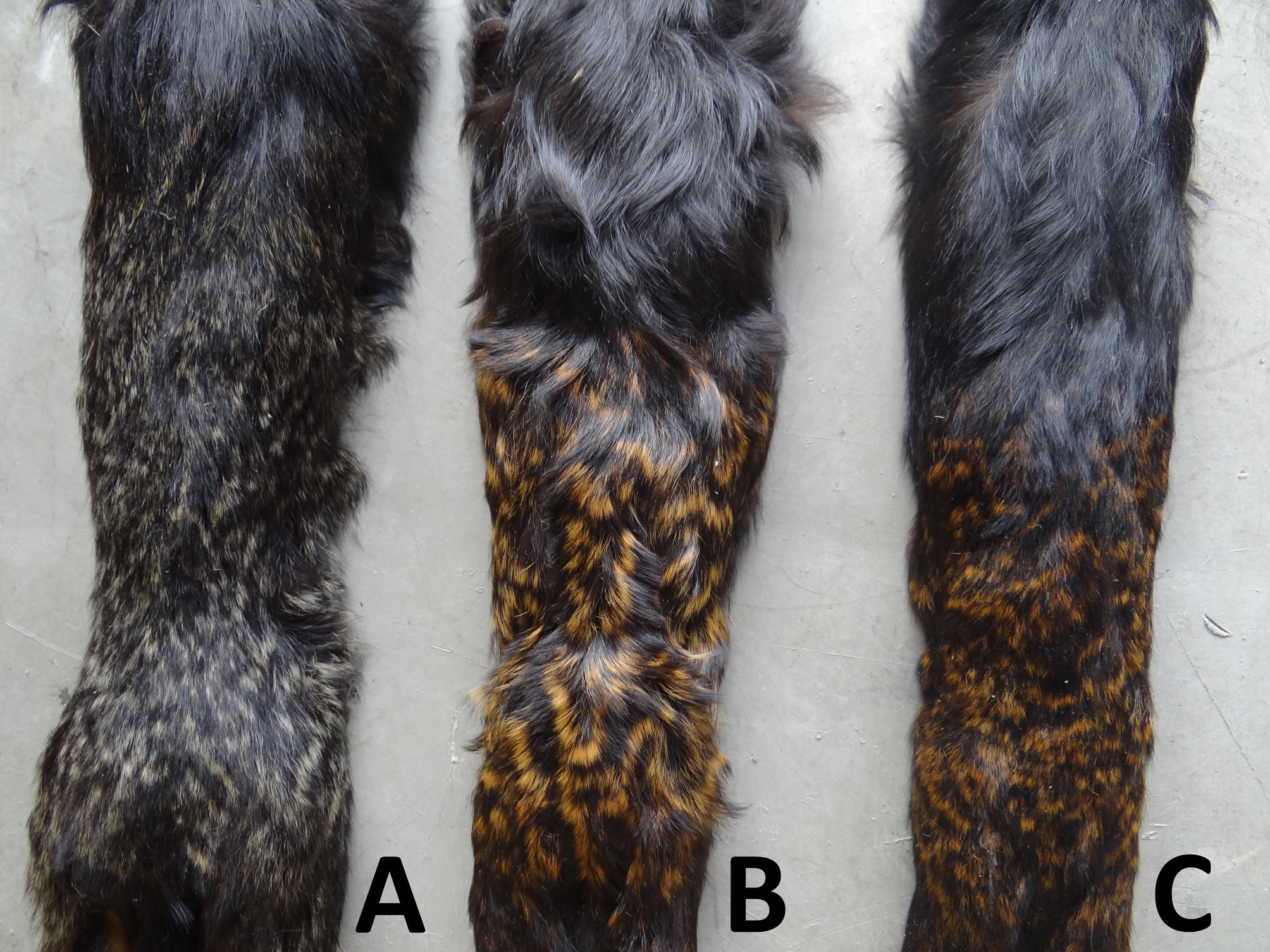

Results of the present study disagree with Hershkovitz´s (1977) appraisal. Specimens occurring on each bank of the Tocantins River have a discrete pattern of pelage coloration and no variation was recorded. Comparing samples from both sides of Tocantins River, S. ursulus can be easily distinguished from S. niger by the following qualitative characteristics ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ): 1) striated hairs usually extend from the scapular region to the base of the tail, and only a narrow proximal portion of the thighs, rarely reaching the knees (in S. niger the agouti hairs are distributed from the mid-dorsum, from the sub-scapular region, and usually extending to the lumbar region, thighs and knee portions, but rarely reach the base of the tail), 2) the intermediary stripe of agouti hairs is brilliant golden buffy (it is dark and opaque ochraceous in S. niger ), 3) the length of the intermediary stripe is about 5.0–5.5 mm in S. ursulus (in S. niger it is shorter, 4.0 mm), 4) dorsal hairs present irregular directions, disheveled (they are homogeneously parallel and posteriorly directed in S. niger ), and 5) face, hands and fingers are not notably haired in S. ursulus (it is haired in S. niger ).

From S. midas , S. ursulus can be easily distinguished ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ) in presenting 1) blackish hairs on the hands and feet (they are orange to ochraceous in S. midas ), 2) the intermediary stripe of dorsal hairs is bright and golden buffy (it is pale ochraceous to light grayish in S. midas ), 3) the intermediary dorsal stripe in S. ursulus is 5.0–5.5 mm (it is shorter, 2.5–3.2 mm, in S. midas ), and 3) the striated hairs reach to knees, while in S. midas they extend posteriorly, reaching the shank.

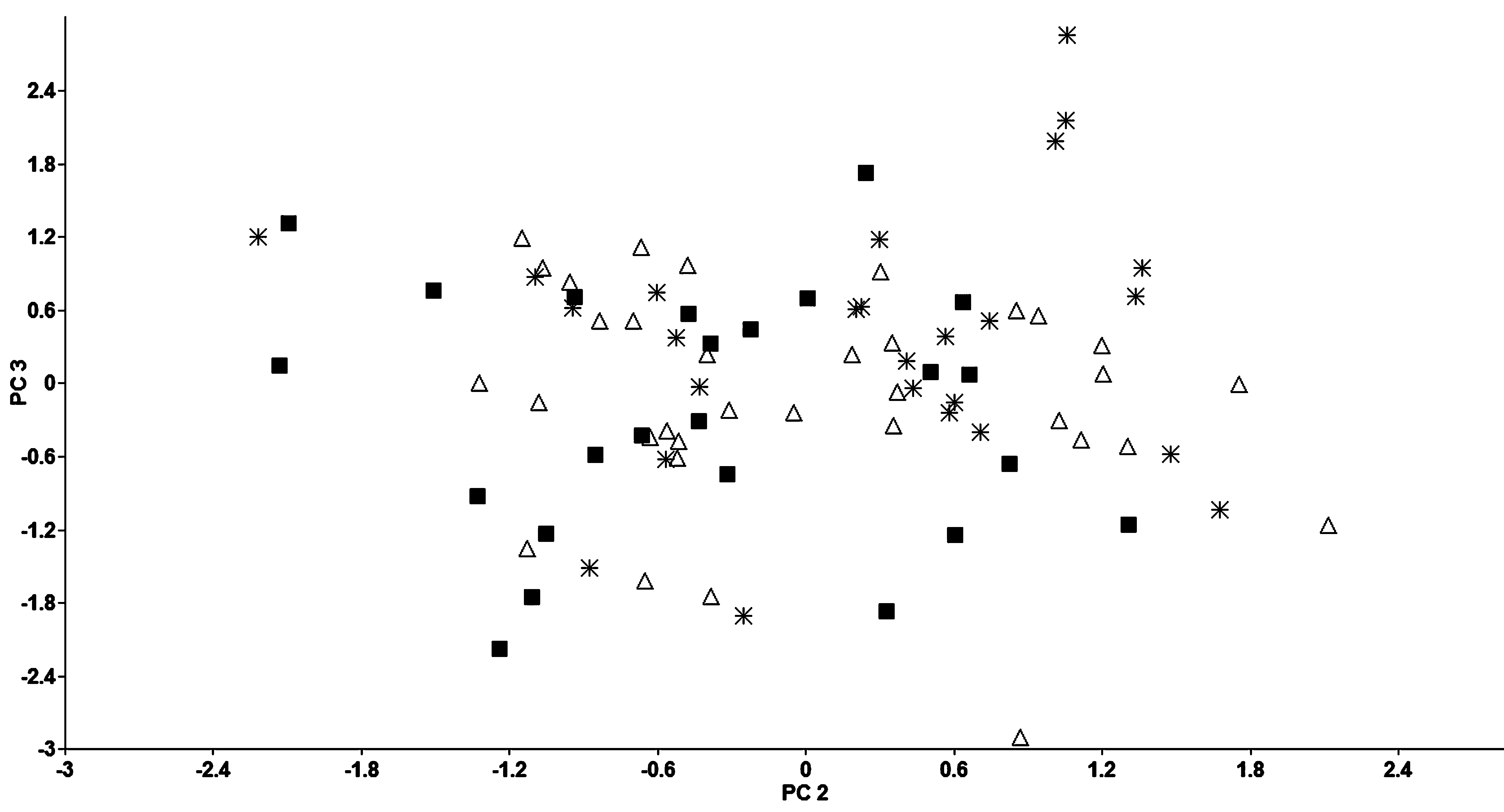

Thus, considering current criteria for the definition of species based on unique characters to delimit more inclusive groups (Cracraft 1983, Pinna 1999, Wiley & Lieberman 2011), the morphological divergence ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 ), and the disjunct distribution of the two phenotypes, separated by the Tocantins River ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ), the recognition of S. ursulus is necessary to better express the evolutionary diversity of the genus Saguinus . Moreover, these results corroborate with the genetic divergence revealed by Vallinoto et al. (2006), and contribute to our understanding of biogeographical patterns and their recent evolution in the Amazon (Haffer 1992, Goldani et al. 2006, Ribas et al. 2012), with the differentiation of S. ursulus and S. niger in accordance with the robust biogeographical hypothesis which identifies the Belém and Xingu centers of diversity as drivers of speciation in the eastern Amazon (see Ribas et al. 2012).

Acknowledgments

We thank the curators that allowed us to examine the material under their care: Luiz Flamarion de Oliveira (MNRJ), José de Souza e Silva Júnior (MPEG), Bruce D. Patterson (FMNH), and Robert S. Voss (AMNH). We are most grateful to José de Souza e Silva Júnior for making available the many unpublished records of S. niger and S. umbratus from the States of Pará and Maranhão, and Elisandra A. Chiquito for drawing the map. We kindly thank to Alexandre R. Percequillo, Anthony B. Rylands, and Robert S. Voss, for their valuable suggestions on the text and about Saguinus taxonomy. We are in debt and thank very much Eileen Westwig (AMNH) and Nora Lang (ZMB) for assistance and in providing information about type series and old literature. This study has supported of CNPq (process number 555491/2009-9).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.