Hippotragus niger (Harris, 1838)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6512484 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6581658 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F50713-990D-FFB7-064F-F99BF879FB3E |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Hippotragus niger |

| status |

|

Southern Sable Antelope

French: Hippotrague noir / German: Rappenantilope / Spanish: Hipotrago sable meridional

Other common names: Swartwitpens; Black-black Sable (niger, Giant Sable ( variani)

Taxonomy. Aigocerus niger Harris, 1838 .

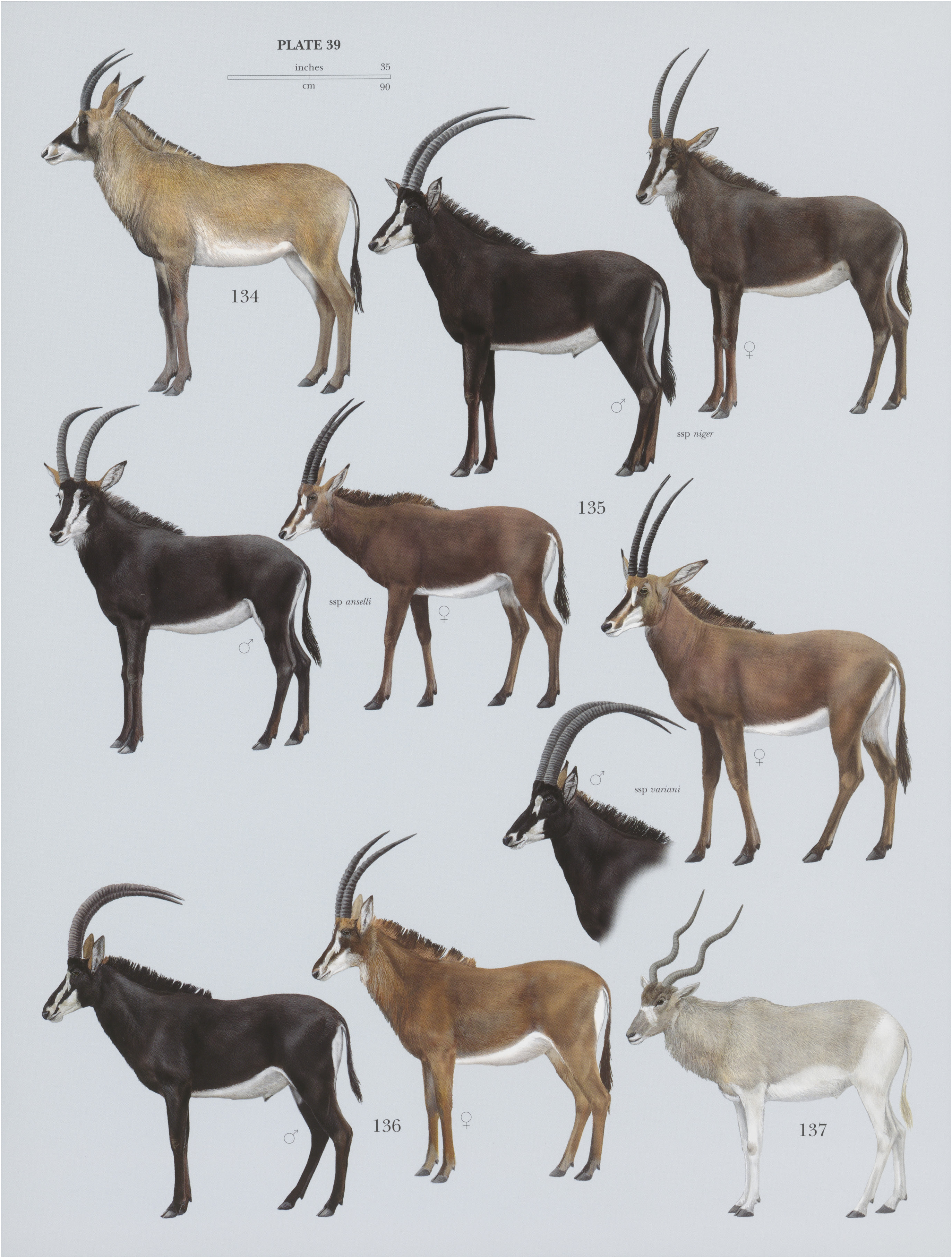

Cashan Range, Magaliesburg, near Pretoria, South Africa.

The subspecies are fairly well marked, differing in size, the color of the female (the adult male is always black), the form of the white face stripes, and the size of the horns. The mtDNA haplotypes are somewhat mixed, as one expects in the case of subspecies, but there are haplotypes typical of each of them. There is also a “ghost” of what may have been another subspecies in western Tanzania, from Wembere south to Rungwe. It is now largely introgressed by Roosevelt's Sable Antelope (H. roosevelt), so that externally it resembles this species, but the DNA in some individuals is most typical of the Southern Sable Antelope subspecies variani. Four subspecies are recognized.

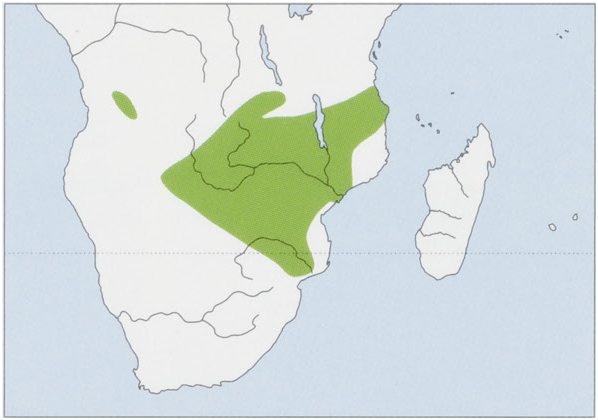

Subspecies and Distribution.

H.n.nigerHarris,1838—SoftheZambeziRiver.

H.n.kirkiiGray,1872—NoftheZambeziRiver,inKatanga(DRCongo)andZambiaWoftheMuchingaEscarpment.

H. n. variani Thomas, 1916 — C Angola. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 185-194 cm, tail 44-53 cm, shoulder height 135-140 cm, ear 25-28 cm, hindfoot 51-54 cm; weight 180-230 kg (males) and 160-180 kg (females). The Southern Sable Antelope is smaller and more sexually dimorphic (particularly in horn size) than the Roan Antelope ( H. equinus ). Horns are much shorter, and much less curved, in females, but very long and strongly curved backward in males; they are more slender and more compressed than those of the Roan Antelope . Females and young are black to deep rich chestnut, the color varying geographically; males become black at about three years of age, the backs of the ears remaining reddish-brown. The underparts and hind edge of the buttocks are strikingly and sharply white, as are the lower jaw and the end of the muzzle. There is a white stripe near the base of the horn that typically goes down the face to meet the white of the muzzle, leaving a black stripe between it and the white of the lowerjaw. With age, the lower part of this white stripe tends to darken, and in adults of the subspecies variani (known as the “Giant Sable”), only the upper part of the stripe, the patch down to the medial side of the eye, generally remains. There is a high mane, often not as dark as the body color, down the neck. Newborns are pale yellowish-brown, with only very faint markings, and closely resemble Roan Antelope neonates. The diploid chromosome number is 60; all chromosomes are acrocentric or subtelocentric. The subspecies tend to differ strongly, although (as one expects of subspecies) there are individuals that cannot be positively assigned to a subspecies. In the subspecies niger , sometimes called the “Black-black Sable,” females and young males are extremely dark red-brown, nearly but not quite black, almost like the adult males. In the subspecies kirkii , females are usually rich chocolate-brown, although some darker females occur, particularly in the western part of the distribution where it grades into niger ; it averages larger in body size than niger , but the horns are smaller. The subspecies anselli is the smallest, with a relatively narrow skull; the color of the female resembles that of kirkii , and in both sexes the white face stripes flanking the muzzle are broader, on average, than in the other subspecies. The subspecies variani is on average larger and longer-horned than other subspecies (although its measurements overlap with nigerand kirkii ), and the female is usually more chestnut-colored than in other subspecies. This subspecies is particularly distinguished by the white face stripe being restricted to a white oblong in front of the median side of the eye, or only vaguely continued along the snout. These differing patterns of white face stripes essentially represent different stages of heterochrony (thatis, adults retaining juvenile features, or developing into “superadults”). In sable antelopes in general, with age, the anterior half of the white stripes on the face becomes narrower and more invaded by the general dark color of the nose and cheeks. The smallest subspecies, anselli , which on average has the widest stripes, is the most paedomorphic (retaining the most juvenile characteristics as an adult), and the largest subspecies, variani, with the stripes normally restricted to the region medial to the eye, is hypermorphic (all adults resemble the aged adults of the other subspecies). Dental formula is 1 0/3, C0/1,P3/3,M 3/3 (x2) = 32. Full dental eruption is complete at 44 months.

Habitat. Southern Sable Antelopes are restricted to the Miombo woodland zone, which is relatively open, with a grassy understory. They tend to range out into the grasslands in the dry season, returning to the woodlands at or before the beginning of the rains. In Pilanesberg National Park, South Africa, they choose north-facing slopes during the wet season and move down to the valleys during the dry season. In general, they avoid the more open habitats, the pediments, and secondary grasslands. They are very water-dependent. Mortality in the wild can be caused by poor nutrition, especially after drought or competition with cattle; tick and louse infestation; parasites, especially babesiosis (caused by the protozoan Babesia); predation by Lions (Panthera leo), Leopards (P. pardus), and hyenas; and (among young males) fighting with territorial males.

Food and Feeding. Southern Sable Antelopes eat grass, with some forbs and a little browse. It has been noticed that they especially frequent areas around termite mounds and drainage lines, where the forage is lusher than elsewhere. Stable isotope analysis of dental enamel has more or less corroborated the field observations that the diet is in fact 100% grass. They visit salt licks for their mineral content, and have even been known to chew bones. In Pilanesberg, their diet consisted mainly of seven grass species, of which only four were eaten throughout much of the year: Chrysopogon serrulatus, Panicum maximum, Themeda triandra, and Heteropogon contortus, these contributing about 90% of the diet. The last three species were recorded as also being favored in Zimbabwe and elsewhere in South Africa. The grass that they eat is at heights of 50-300 mm, with a high leaf-to-stem ratio. Chrysopogon is little used by zebra and hartebeest, their main presumed competitors, during the dry period, providing niche separation from these species.

Breeding. Southern Sables are not strictly seasonal breeders, but they have distinct birth peaks, typically January to March. Both sexes reach sexual maturity before they are physically mature; males reach physical maturity at 7-8 years of age and females at 5-6 years, but sexual maturity occurs at about two years in females and 18 months in males. At about two years of age, young males leave their natal herd to join bachelor groups of 2-12 individuals. In Zimbabwe, females’ horns appear to reach their full adult length, about 67-69 cm, at about eight years, and males at about the same time, at the larger size of about 94-97 cm. A breeding bull displays to the herd of cows with a lateral display with tail raised, head erect, but chin pulled in. Young bulls in the herd display submissive postures to him, with head down and tail held tightly in. Gestation is eight months (240-280 days). Calves remain in hiding for about three weeks after birth, and the female may stay with them for long periods, the calves hidden in tall grasses and the mothers feeding in nearby thickets. Females remain in the herds, but young males are increasingly harassed by breeding bulls until they leave the herd at about two years of age. Males live in small bachelor herds before attempting to become territorial, which they do at about 5-6 years of age.

Activity patterns. Southern Sable Antelopes are most active in early morning and late afternoon, and lie and chew their cud, or graze fitfully, during the heat of the day. They move to water sources regularly. At night, the herd moves together for a short distance, then lies down, chews their cud, and grazes at intervals until dawn, moving farther while grazing at night than by day.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home ranges of Southern Sable Antelopes have been measured at 12-25 km? in Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe, in Pilanesberg, and in the Luando Reserve in Angola, but as much as 320 km ® in eastern Zambia, and even occasionally in Kruger National Park. Southern Sable Antelopeslive in herds of 15-25, gathering into larger groups in areas of good grazing in the dry season, and dividing into small groups in the rainy season. Neighboring herds are antagonistic. Within the herds, there is a stable hierarchy, usually based on age, although the dominant female loses rank when in poor health, or if she breaks a horn. The dominant female or females lead the herd during progressions, for example to feeding areas and water points. Within its home range, a herd remains in one small area, sometimes for a week or more, then shifts to another area. In Pilanesberg, there is also a noticeable seasonal shift, moving down into the valleys in the dry season where the water table is higher, so the grasses are greener. There are three classes of territorial bulls: central bulls, with highest status and having continuous contact with the breeding herd; peripheral bulls, with lower status and occasionally making contact with the breeding herd; and outside bulls, with the lowest status and having virtually no contact with the breeding herd. Territories are 25-40 ha. A territorial male patrols regular pathways, sniffing the dung and urine of other Southern Sable Antelopes as he goes, defecating every couple of hundred meters, and pawing the ground with his tail raised. He often beats the vegetation with his horns, twisting and breaking branches. When resting, he moves into dense cover. He may follow a herd, and ifit enters his territory, he tries to block any movement out of it. He may enter the territory of another bull when a herd is there, and even defeat the territory owner. A bull Southern Sable has a sparring invitation; the challenger approaches with his head at shoulder level and presses or rubs his forehead and horns against the other bull's neck, shoulder, or rump.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I (Giant Sable, subspecies variant). Classified as Least Concern as a species on The IUCN Red List, but the Giant Sable is classified separately as Critically Endangered. Small populations of the Giant Sable survived the civil war in Angola, but in one region, only adult females survived. They bred with a male Roan Antelope , and several hybrid calves were born, which were removed. There are nearly 2000 Southern Sable Antelopes in Kruger National Park, about 1500 elsewhere in South Africa, 22,000 in Zimbabwe, 3000 in Botswana, and 300 in Namibia. In all these countries, the status is considered reasonably satisfactory. Numbers of Southern Sable Antelopes in Mozambique are unknown, although they are said to be decreasing. The status in Zambian national parksis satisfactory, and there are about 2000 Southern Sable Antelopes in Malawi.

Bibliography. Estes (1991a, 1994b, 2000), Magome (1992), Sekulic (1978), Skinner & Chimimba (2005), Sponheimer et al. (2003), Wilson & Hirst (1977).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Hippotragus niger

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2011 |

Aigocerus niger

| Harris 1838 |