Iguanodon hollingtoniensis (Lydekker, 1889)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12193 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F9879B-325D-FF97-FF03-FDE5FC4D7B3C |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Iguanodon hollingtoniensis |

| status |

|

IGUANODON HOLLINGTONIENSIS LYDEKKER, 1889

Norman (2010) described, albeit briefly, the anatomical basis upon which Lydekker established the Wadhurst Clay Formation taxon ( I. hollingtoniensis Lydekker, 1889 ) whose remains were collected from the same geographical area and horizon as B. dawsoni and Hy. fittoni . It was concluded that I. hollingtoniensis was a nomen dubium and its skeletal material could be assigned to Hy. fittoni . A detailed review and description of the original type and referred material of the latter species is now necessary. Norman’s proposal that a single taxon (incorporating I. fittoni and I. hollingtoniensis ) be recognized under the binomial Hypselospinus fittoni ( Lydekker, 1889) has been challenged firstly by Paul (2008) who later made specific taxonomic proposals ( Paul, 2012), and secondly when an alternative set of taxonomic proposals were made by Carpenter & Ishida (2010).

History

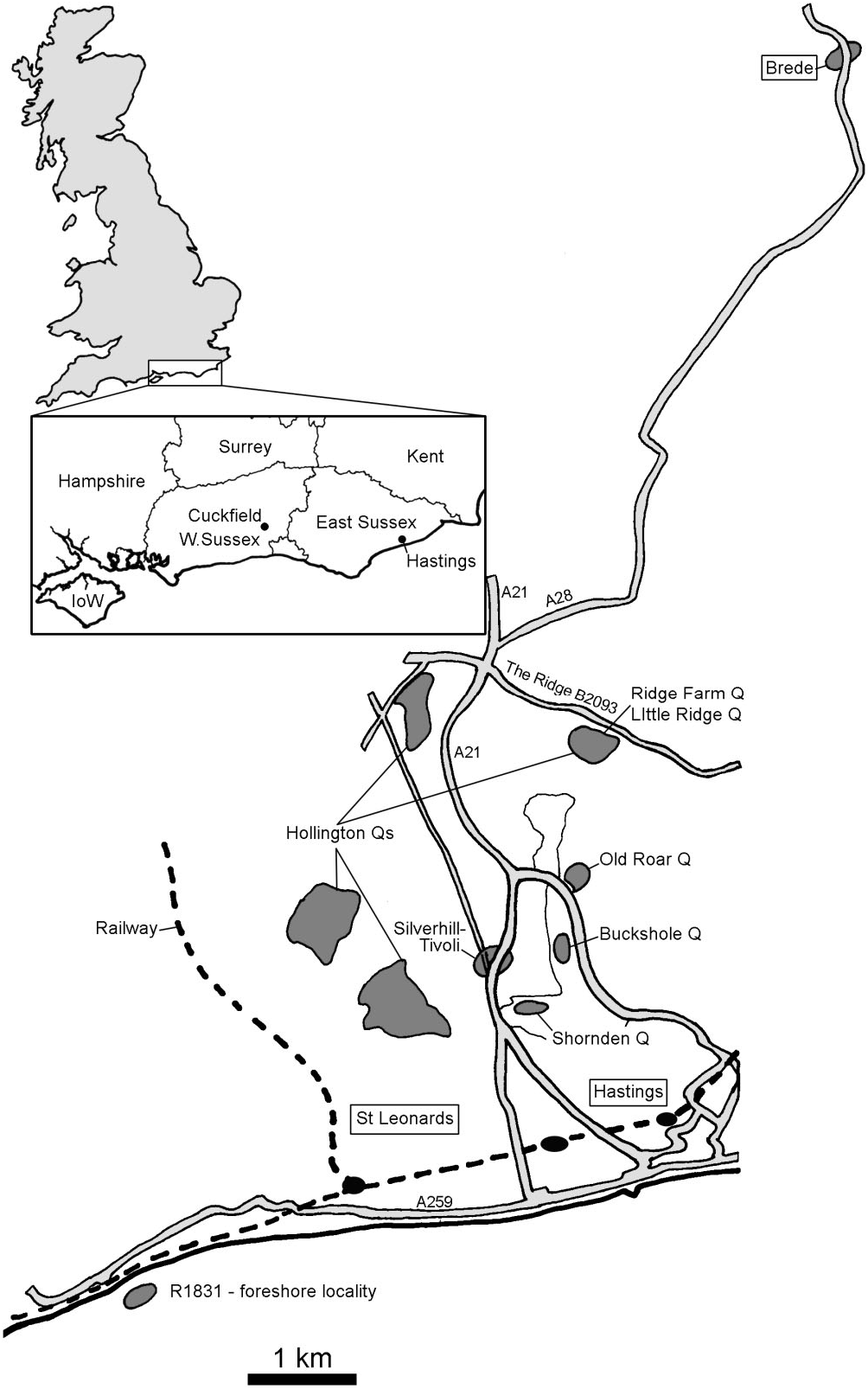

Between 1884 and 1889 Charles Dawson collected the major portion of an associated partial skeleton of at least one Iguanodon -like specimen from Ridge Farm Quarry near Hastings ( Brooks, 2011); this location was referred to as either ‘Hollington’ or ‘Holllington Quarry’ ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). The circumstances surrounding the original discovery of this material – its apparent piecemeal collection, as well as its phased acquisition by the Natural History Museum – add unwanted uncertainty to claimed associations. The brief formal descriptions and catalogue notes of Lydekker (1889, 1890a, b) help to clarify some of these matters, but errors and inconsistencies (even in Lydekker’s accounts) confirm to readers in the present day that an air of confusion must have been created by nonsystematic collecting procedures and (possibly) anecdotal recollections. As alluded to above, it was also the case that Dawson was taken on by Lydekker, to assist with the documentation of the remains from Hastings. The archives of the Natural History Museum contain no letters, site maps, or notes pertaining to the original excavations by Charles Dawson. Similar problems pertain in the case of B. dawsoni ( Norman, 2011a) .

The holotype NHMUK R1148 includes specimens allocated with the registered numbers R1629 and R1632 , which were collected from the same quarry. As evidence of association, some specimens, for example the metatarsals of the left pes (MtIII: NHMUK R1148 and MtII: NHMUK R1629 ) fit together perfectly ( Fig. 11A–H View Figure 11 ). Additional material assigned to registered numbers NHMUK R811 , R811 a, b (including sacral and pelvic bones) as well as NHMUK R604 (cervical, dorsal, and caudal vertebrae, some imperfectly preserved ribs, and some broken tooth fragments) were also collected from this quarry and are, if not part of the type series, commensurate, and show the same preservational characteristics and almost no duplication of elements. It must be noted, however, that an ischial shaft fragment of NHMUK R1629 ( Fig. 17 View Figure 17 ) duplicates one of the two ischia associated with NHMUK R811 ( Fig. 31B View Figure 31 ). This ischium fragment alone suggests that two commensurate and osteologically identical ornithopod skeletons must have been collected from a site that Dawson recorded as the same locality .

A very flattened and broken left ilium NHMUK R811(b) (figured by Norman, 2010: fig. 8C, D – but as a reversed image – see Fig. 30B, C View Figure 30 ) was claimed to be associated with material assigned to NHMUK R811 and R604 ( Lydekker, 1890b: 263) and this duplicates a small portion of the preacetabular process preserved in NHMUK R1629 ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 ). However, the association of the material referred to as NHMUK R811, R811(a), and R811(b) is compromised because: (1) R811(a) – a partial right pubis was formerly assigned to ‘ I. ’ dawsoni ( Lydekker, 1888b: 199–200) ; and (2) the flattened ilium (NHMUK R811b) was not mentioned in Lydekker’s (1888b) first catalogue but was later recorded as having been purchased separately in 1884 ( Lydekker, 1890a: 264).

NHMUK R1148

Note. This specimen comprises four vertebral fragments from the dorsal column, a right femur, proximal right tibia, and right metatarsal III. This material was assigned to I. bernissartensis originally ( Lydekker, 1888b: 217), with the cautionary note that ‘these specimens might belong to I. dawsoni ’.

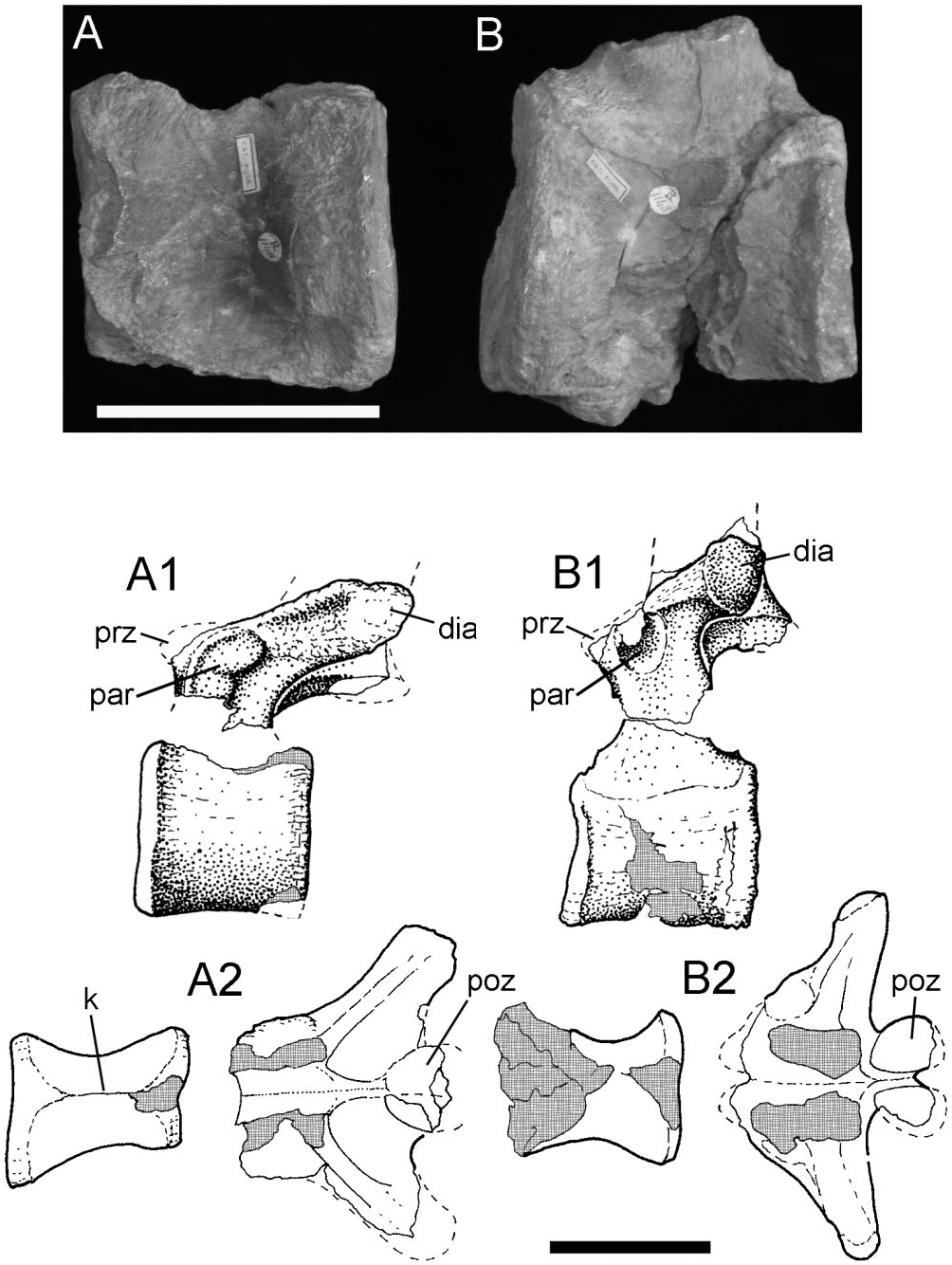

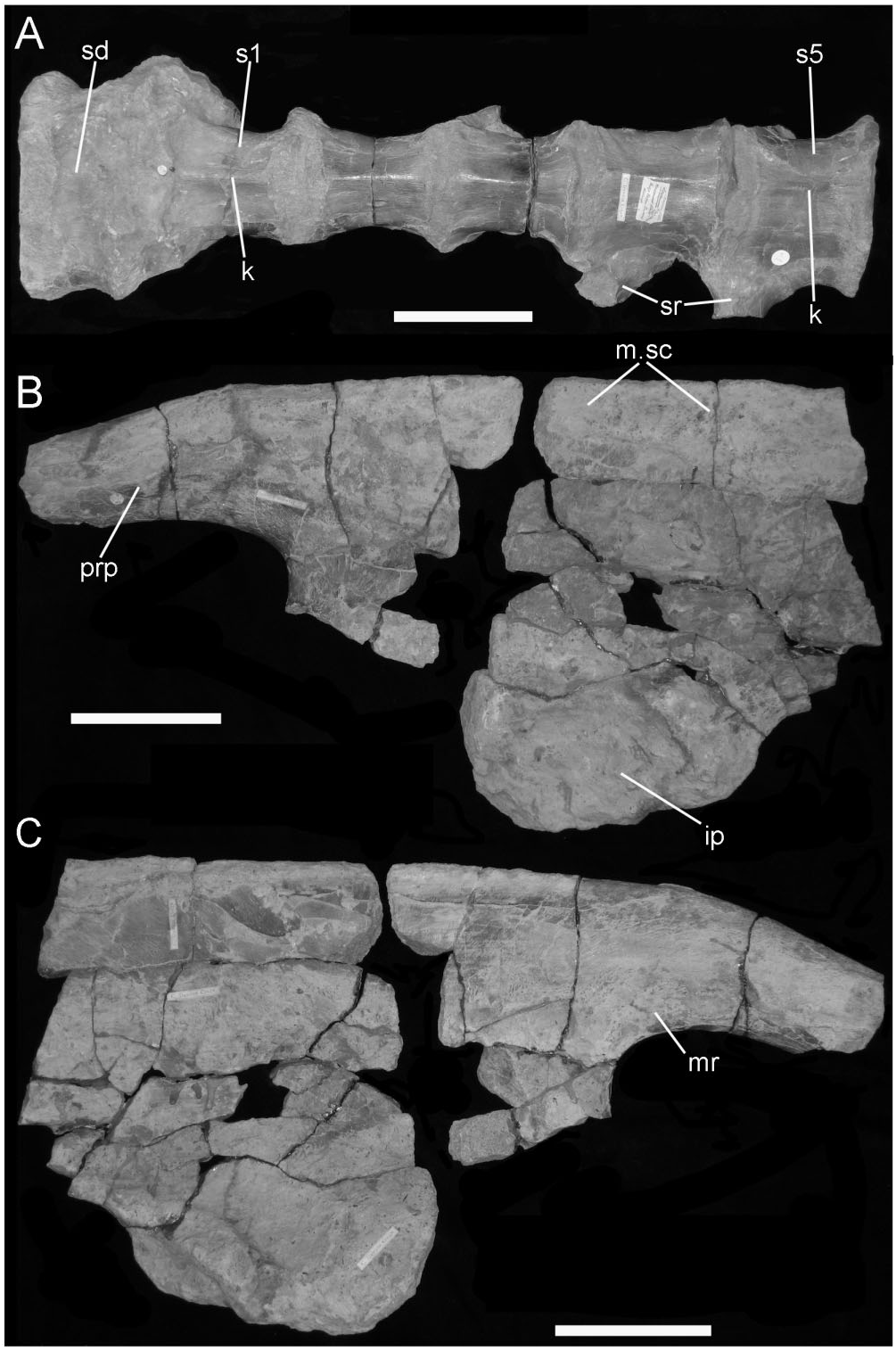

Vertebral column ( Fig. 12 View Figure 12 )

Two incomplete neural arches, each of which comprises a well-preserved platform and the sheared-off base of the neural spine. The first neural arch ( Fig. 12A View Figure 12 1 View Figure 1 , A 2 View Figure 2 ) shows details of the rib articulation and the transverse process. The capitular facet (parapophysis – par) is large and positioned on the anterior half of the pedicel (adjacent to the prezygapophysis); its facet extends posterolaterally along the edge of the transverse process; the latter is elongate, robust, and obliquely orientated when compared with the other example; its distal tip bears a diapophyseal facet. The postzygapophyses overhang the posterior margin of the neural arch and the neural spine is positioned posteriorly on the neural arch platform. All of these features suggest that this neural arch comes from a relatively anterior position in the dorsal series (d4−d6) because the combination of features (position and size of parapophysis, robust and oblique transverse process, and backward extension of the posterior zygapophyses) echoes the morphology in the posterior cervical−anterior dorsal section of the column.

The other neural arch ( Fig. 12B View Figure 12 ) has a more discrete, almost circular, parapophysis tucked into the recess between the prezygapophysis (prz) and the base of the transverse process. The posterior margin of the parapophysis stands clear of the side wall of the neural arch because there is a recess between it and the adjacent buttress for the transverse process. The trans- verse process is elongate, moderately robust and projects less obliquely from the neural platform; its distal tip forms a large, rugose facet (diapophysis – dia) for the tuberculum of its rib. The posterior edge of the transverse process forms a shelf that curves toward the base of the neural spine and merges with the anterolateral margin of the postzygapophysis (poz). The base of the neural spine rises from the midline and the anterior and posterior edges converge slightly before being abruptly truncated by breakage. The position of the parapophysis on the neural arch suggests that this was probably from a mid-dorsal vertebra (d7−d9).

The centra ( Fig. 12A, B View Figure 12 ) have had their neural arches sheared away, rather than their being separated along an imperfectly fused neurocentral suture. The centra are generally spool-shaped, but the sides are compressed and distorted. The ventral edge of the centrum forms a narrow keel (k). The articular faces are flattened with a central concavity; the margins of the articular surfaces are everted, thickened, and rugose as if for the attachment of powerful collateral ligaments. These centra appear, from their proportions, to have come from the anterior half of the dorsal series but probably never attached to the neural arches as shown here.

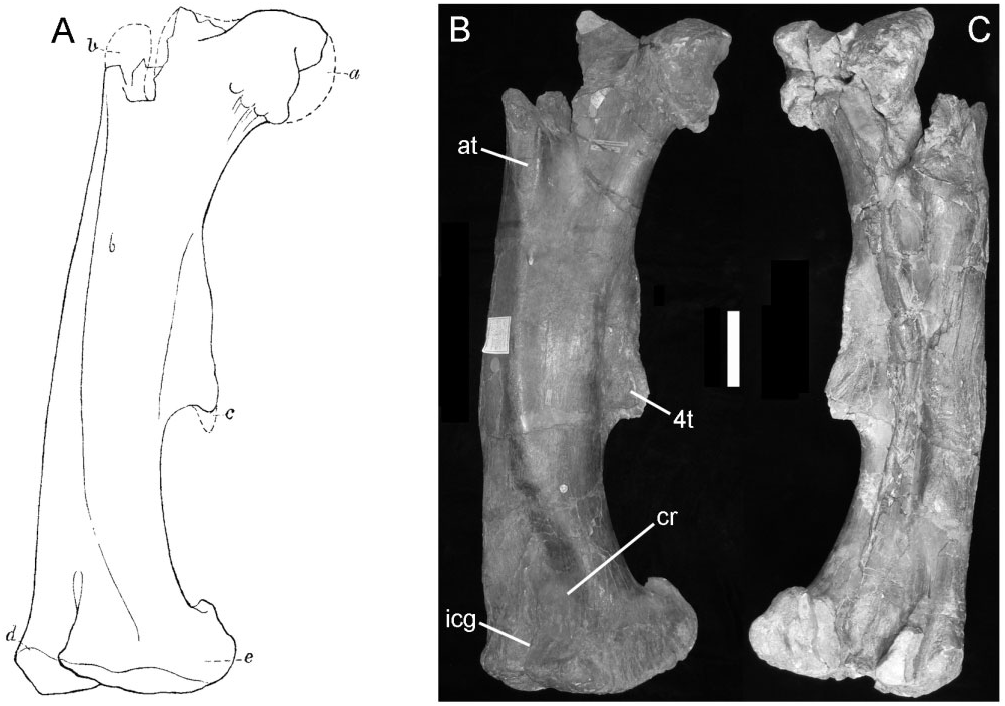

Femur

The majority of the right femur ( Fig. 4B, C View Figure 4 ) is well preserved, although it is damaged proximally and shows evidence of having been crushed along the length of the shaft and there is a depressed fracture on the shaft above the medial condyle (cr). The proximal end preserves part of a large, medially offset, globular, femoral condyle. The anterior trochanter (at) is notably thickened along its anterior edge and has a bevelled, rugose, anterolateral facet that extends distally onto the base of a prominent ridge that runs diagonally across the shaft of the femur to merge with the medial side of the distal condyle ( Fig. 4B View Figure 4 ). The thickness of the anterior trochanter suggests that it would have masked the anterolateral portion of the greater trochanter. The shaft of the femur is angular and bowed along its length. There is a very large, heavily muscle-scarred, fourth trochanter ( 4t); the distal tip of the trochanter is slightly eroded and may originally have been very slightly pendant (but not as suggested in Lydekker’s sketch; Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ). The overall shape of the femur and position on the shaft of the fourth trochanter are unlike those seen in camptosaur femora ( Galton, 2009; pers. observ. USNM November 2010). The distal end of the femur is marked by a large extensor intercondylar groove (icg) that is nearly enclosed by overgrowth from the adjacent buttresses on the tibial condyles of the femur; again this morphology differs markedly from that seen in camptosaurs, in which the extensor intercondylar groove is deep, but broadly open (pers. observ. USNM November 2010).

So far as this element can be compared with NHMUK R2848 (a femur that has been tentatively referred to B. dawsoni – Norman, 2011a), these two femora appear similar in their shape and proportions and it is considered possible that NHMUK R2848 (femur and scapula – Norman, 2011a) may be referable to Hy. fittoni . Tibia

This bone is represented by its proximal portion only. It shows an expanded articular region with two asymmetric condyles posteriorly, and the base of a robust (but broken) cnemial crest projecting anterolaterally. The shaft is stout and angular-sided and bears a large rugosity on its lateral surface that probably represents anchorage for ligaments that stabilized the proximal end of the fibula.

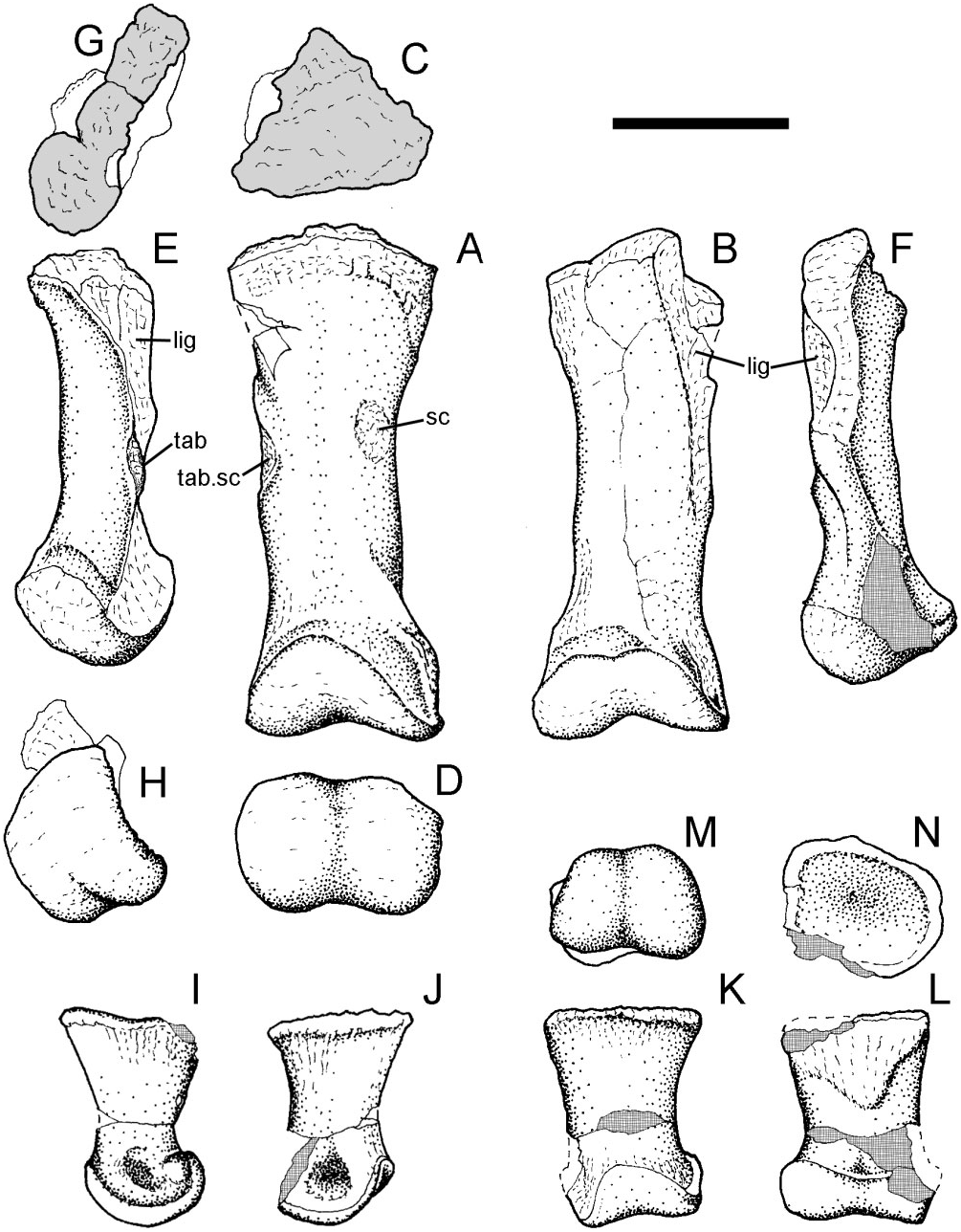

Metatarsal III ( Fig. 11A–D View Figure 11 )

This element is well preserved and large ( 310 mm long), its proximal surface is very rugose, planar, and triangular in proximal view ( Fig. 11C View Figure 11 ): the apex of the triangle is directed posteriorly. The proximal surface was undoubtedly cartilage covered and probably provided an area for attachment of a flattened distal tarsal. The medial surface of the shaft faces obliquely posteromedially and the upper two-thirds is covered with rugosities (lig) reflecting the presence of powerful ligaments that bound the shaft of metatarsal II (NHMUK R1629: Fig. 11E, F View Figure 11 ). Approximately halfway along the length of the metatarsal there is a distinct indentation (tab.sc) on its anteromedial edge for the attachment of a tab of bone that projects from the anterolateral edge of metatarsal II ( Fig. 11E View Figure 11 , tab). The proximal end of the shaft is also rugose laterally (for ligament attachment), and has a wedge-like form that fitted into a complementary recess that ran down the medial surface of the shaft of metatarsal IV. The anterior surface of the shaft of mtIII is concave along its length, and there is a distinct, anterolaterally positioned, thumbprint-shaped scar (sc). The distal portion of this metatarsal lacks ligament scars, which suggests that the metatarsal shafts diverged distally, allowing the toes to diverge when in extension. There is a smooth, slightly asymmetrical, pulley-like, articular surface ( Fig. 11D View Figure 11 ), with depressed areas laterally and medially that are pitted and rugose from the attachment of collateral ligaments.

NHMUK R1148 (R1629)

Note. ‘An associated series of bones belonging to the same individual as the preceding [NHMUK R1148]; from the Wadhurst Clay of Hollington quarry’ ( Lydekker, 1890b: 262). All elements are commensurate and none are duplicates; the femur is a good match for that of NHMUK R1148, and metatarsal II fits neatly against metatarsal III of NHMUK R1148.

Pectoral girdle and forelimb

Scapula: Portions of left and right scapulae are preserved. The right scapula comprises just part of the blade, the proximal and distal ends having been sheared away. The left scapula ( Fig. 13 View Figure 13 ) is reasonably well preserved, although the proximal (coracoglenoid) end is damaged and the distal portion of the blade is missing. The blade is curved posteriorly and bowed medially (following the contour of the ribcage). The preserved part of the acromial buttress (ar) is a thick ridge, which is rugose along its apex and clearly curved forward into the base of the acromion. The external surface of the proximal end of the blade is concave between the acromial buttress and a portion of another thickened buttress above the scapular glenoid. There is also a shallow depression (hr) adjacent to the margin of the glenoid (gl) that represents a ‘stop’ to limit the excursion of the lateral tuberosity of the humerus. The medial surface of the scapula is marked with ligament and muscle attachment scars (m/l.sc). The development of much of this scarring is probably related to the necessity for anchoring the shoulder girdle against the rib-cage in a facultatively quadrupedal animal. Along the scapulocoracoid suture (co.s) there is a wellmarked notch that represents the mediodorsal continuation of the channel associated with the coracoid foramen. The overall similarity in morphology of this partial scapula to that described in the near complete scapula (NHMUK R2848) formerly referred to B. dawsoni ( Norman, 2011a) is noted.

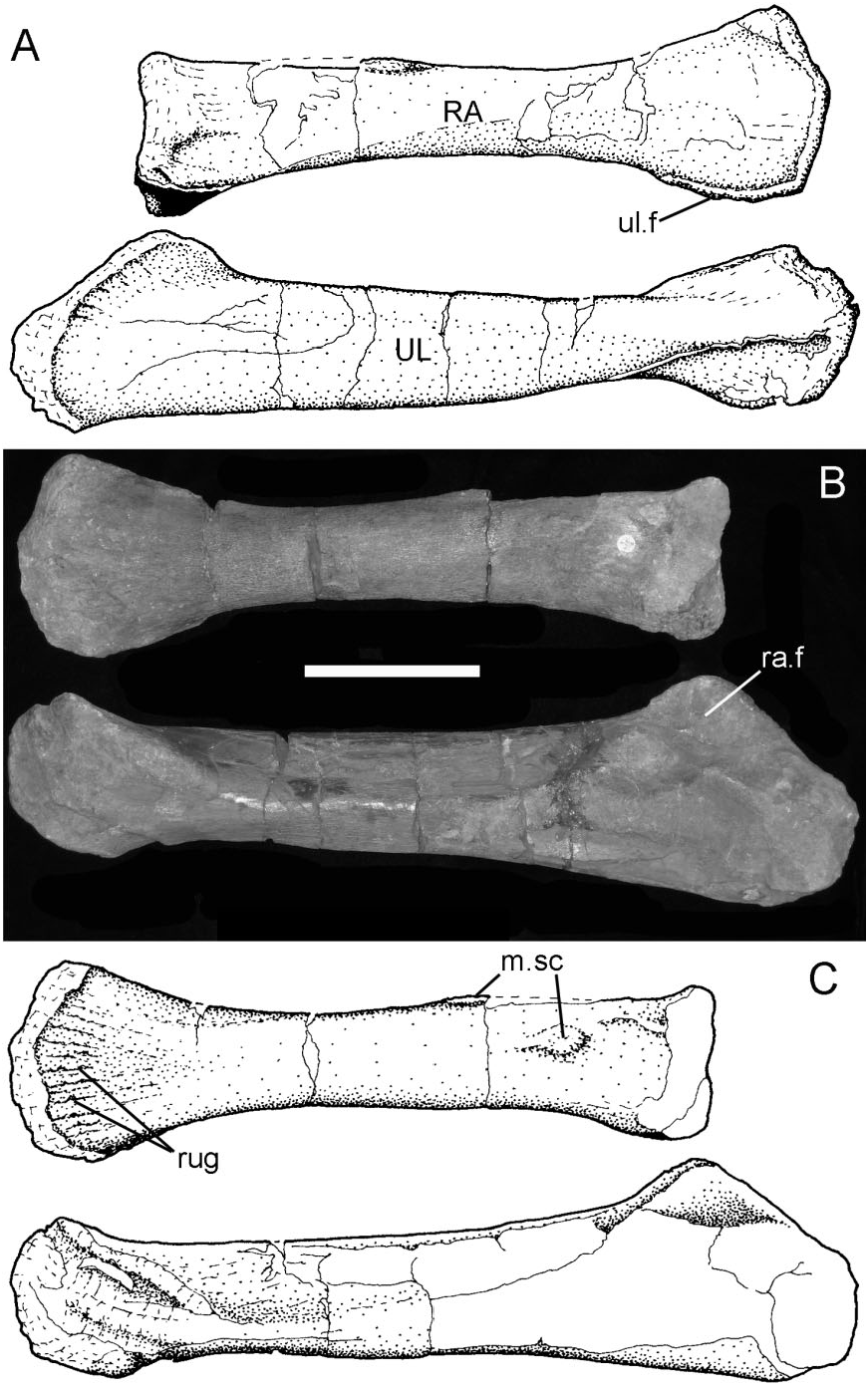

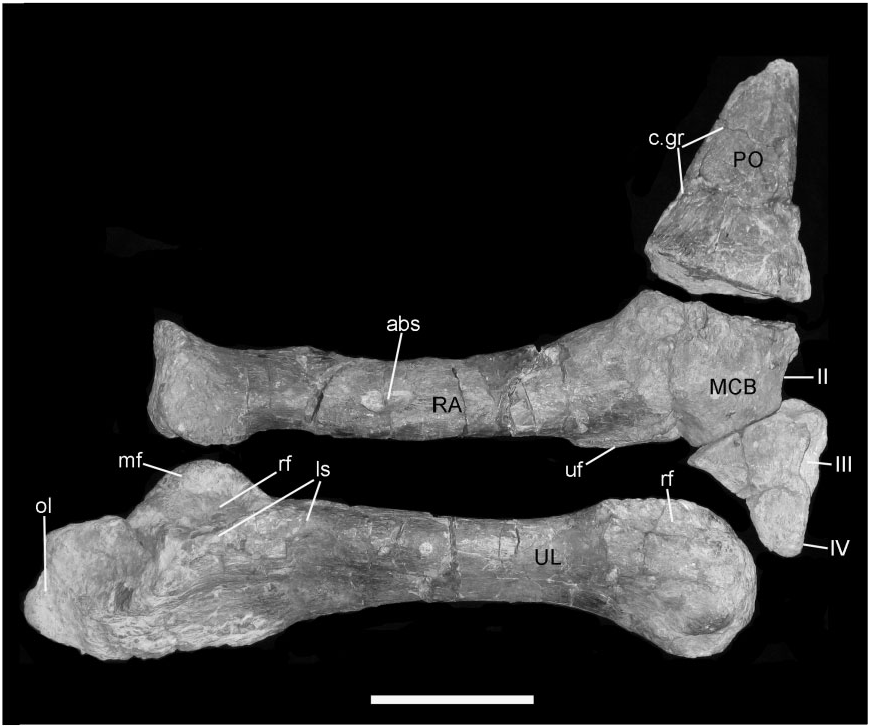

Radius and ulna ( Fig. 14 View Figure 14 ): These two bones are nearly complete, although the ulna is crushed proximally. Both are similar in shape (although smaller and less robust) to those described in B. dawsoni ( Norman 2011a) . The radius ( Fig. 14A View Figure 14 , RA) is 380 mm long and the element is expanded at both ends and tapers in the middle. The proximal articular surface is subcircular, slightly concave, and has thickened margins. The ventral edge of the shaft, adjacent to this articular surface, has a distinct channel [seen also in the associated forelimb of NHMUK R1831 ( Figures 38 View Figure 38 , 40 View Figure 40 ), which was first described and figured by Owen (1872: pl. I)]. The main part of the shaft of the radius is roughly circular in cross-section and narrow, but becomes deeper and laterally compressed distally, where it articulates against the carpometacarpal block. The distal articular surface is convex and rugose. The adjacent surfaces of the shaft, particularly medially, are prominently ridged (rug). The ventral edge of the distal radius has an elongate facet (ul.f) for attachment to the dorsal edge of the ulna. There is another distinct rugose facet (m.sc) on the dorsal surface of the radial shaft about a third of the way from its proximal end and there is another distinct tubercle positioned more proximally on the medial surface of the shaft. The former tubercle may be the insertion site for m. biceps but, if so, it would be unusually distal in its location.

The ulna ( Fig. 14A View Figure 14 , UL) is 480 mm long and is crushed and distorted, and so the olecranon and as- sociated articular areas for the humerus and radius are indistinct. A vertical ‘flange’ projects from the dorsolateral margin of the shaft proximally; this represents a displaced lateral shelf that formed the ventral part of an articular facet for the proximal end of the radius (ra.f). The originally medially positioned vertical wall of the ulna associated with this articular region has been crushed into the shaft of the ulna. Distally, a lateral ridge strengthens the ulnar shaft. The shaft tapers distally before re-expanding to contact the radius dorsomedially (part of this sutural surface is visible in Fig. 14C View Figure 14 ), and developing a convex distal surface that would have articulated against a recess in the proximal surface of the carpometacarpal block.

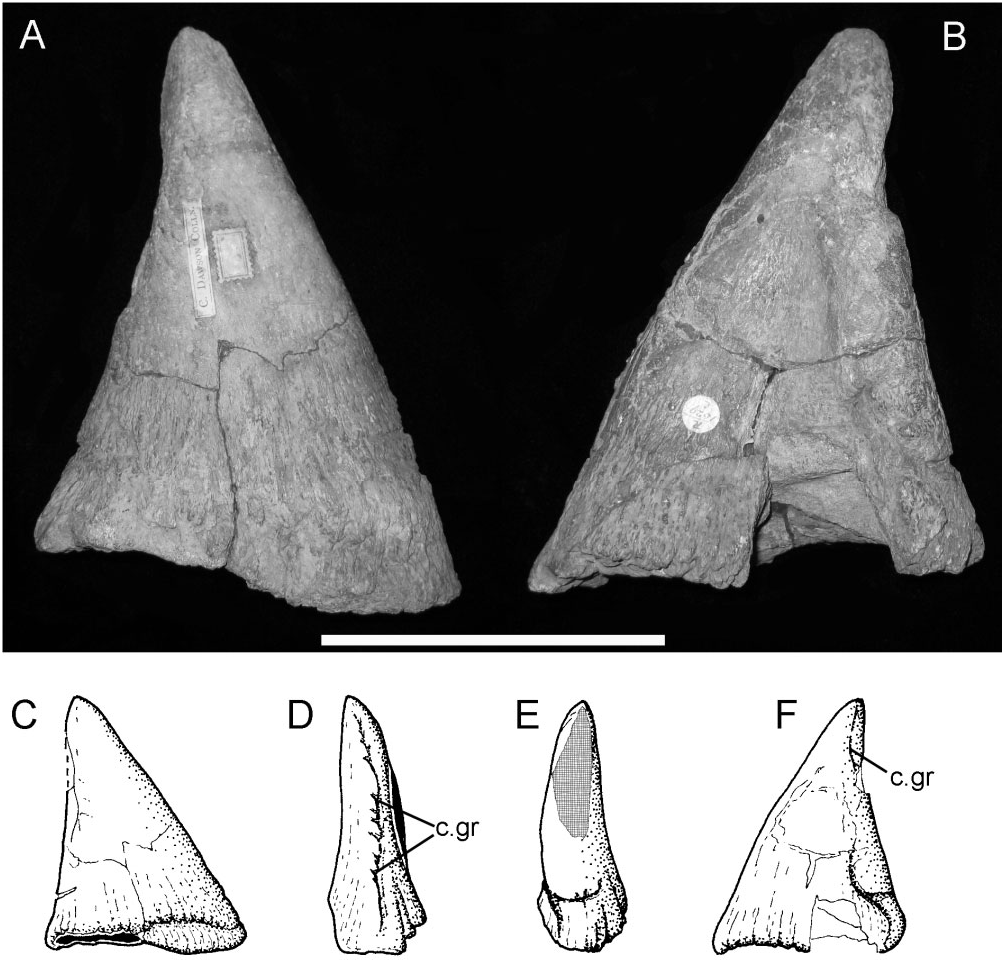

Phalanges: An almost perfect and large ( 160 mm from base to apex) right pollex ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 ) displays what might be termed a classic ‘ Iguanodon ’ morphology, in the sense that it is similar to the ‘nasal horn’ first identified and illustrated by Mantell (1827: pl. XX, fig. 8).

Although generally conical in lateral/medial aspects ( Fig. 15A, B View Figure 15 ), the anterior/posterior views ( Fig. 15D, E View Figure 15 ) show that it was laterally flattened, although the extent of this may be exaggerated a little by post- mortem crushing. This morphology is unlike the more regularly conical pollexes reported in the geologically younger taxa I. bernissartensis ( Norman, 1980) and Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis ( Norman, 1986) . It is also morphologically distinct from the abraded, but apparently truncated, pollex seen in the sympatric contemporary taxon B. dawsoni ( Norman, 2011a: text-figs 18 & 19). The base of the pollex has a sinuous edge ( Fig. 15A, B, C, F View Figure 15 ). The proximal ‘articular’ surface is concave and probably accommodated a disc-shaped proximal phalanx. Above its base, the sides of the pollex converge toward the tip; however, the posterior margin is longer than the anterior and the pollex was therefore naturally tilted forward, a feature that would have been exaggerated further by the oblique orientation of the distal articular surface of metacarpal I. The pollex is curved, slightly medially, along its length ( Fig. 15D, E View Figure 15 ). An ungual (claw) groove is present along almost the entire length of its posterior margin ( Fig. 15D, c View Figure 15 .gr) and although a similar groove is present along its anterior edge ( Fig. 15F, c View Figure 15 .gr), the latter is not so clearly defined.

A partial ungual phalanx of manus digit III is preserved in this collection. It is small (compared with the pollex) and relatively more symmetrical and more laterally compressed than the corresponding phalanx in the manuses of I. bernissartensis and M. atherfieldensis , but is identified as a potential manus digit III ungual because of the longer and more twisted form of a very similar-sized ungual (probably from manus digit II) associated with NHMUK R1632.

A small phalanx possibly of digit II (ph. 2) is strongly asymmetrical, as is typically of this phalanx (taking for comparison the general form of manus phalanges seen in M. atherfieldensis: Norman, 1986, 2011b , unpubl. data) and might well be associated with this individual.

Pelvic girdle and hindlimb

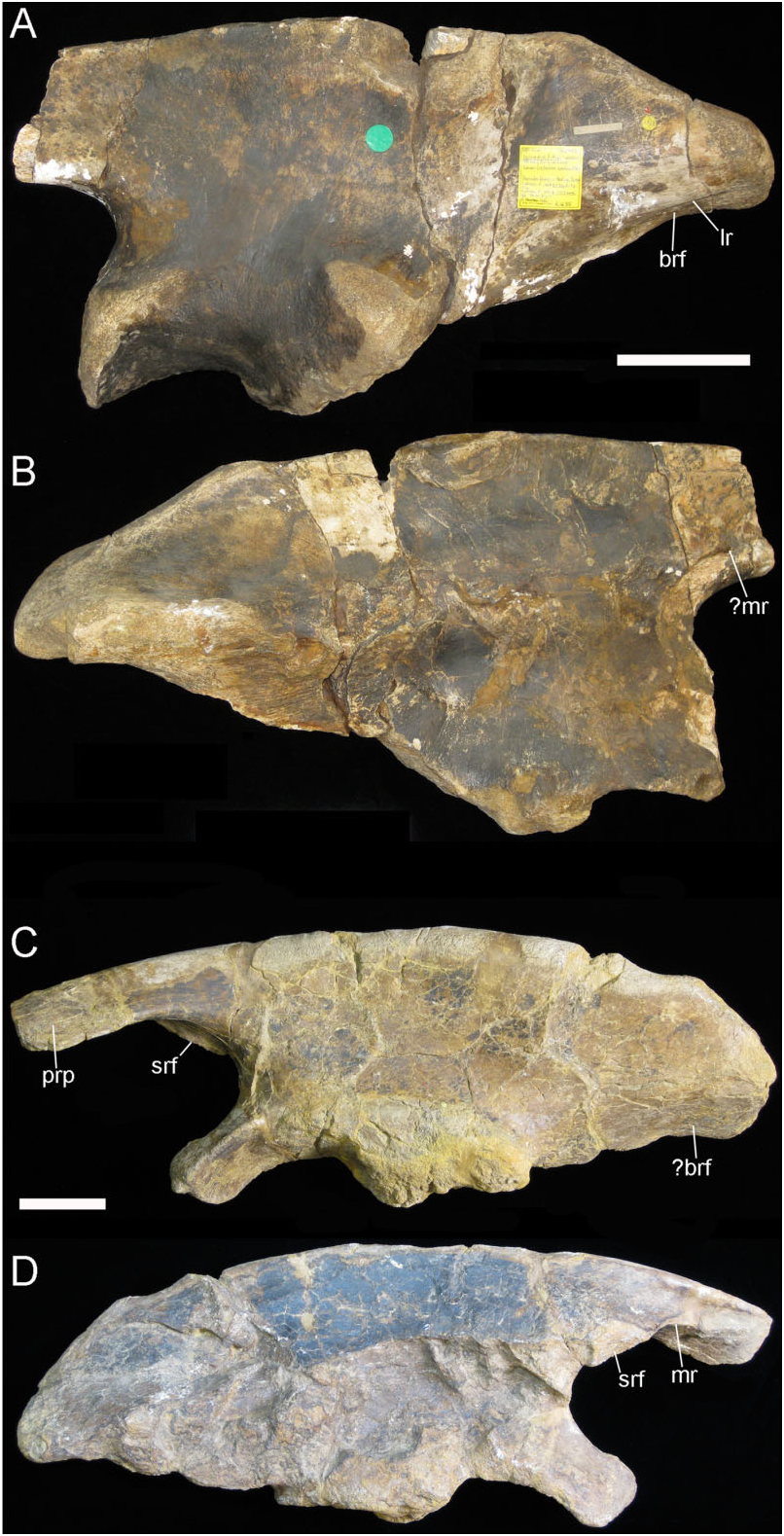

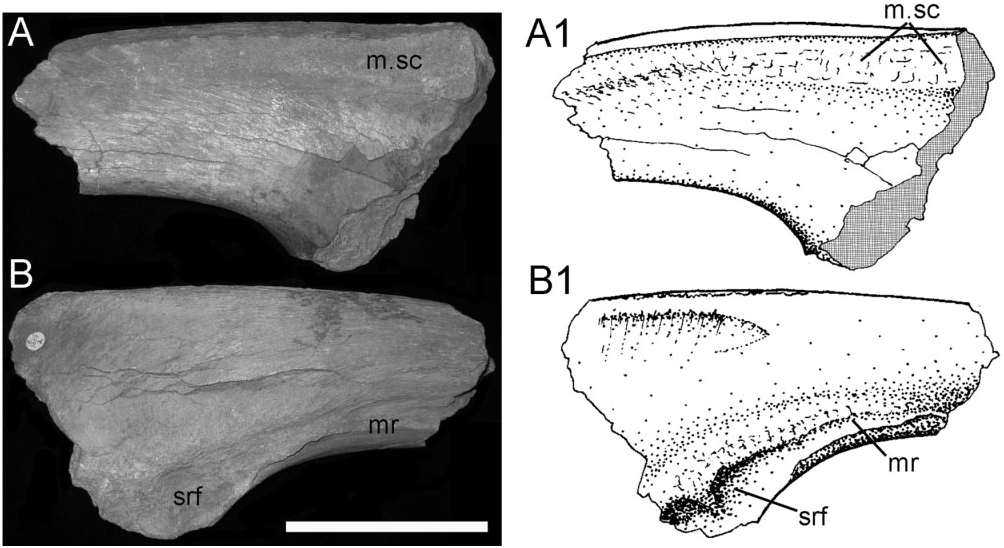

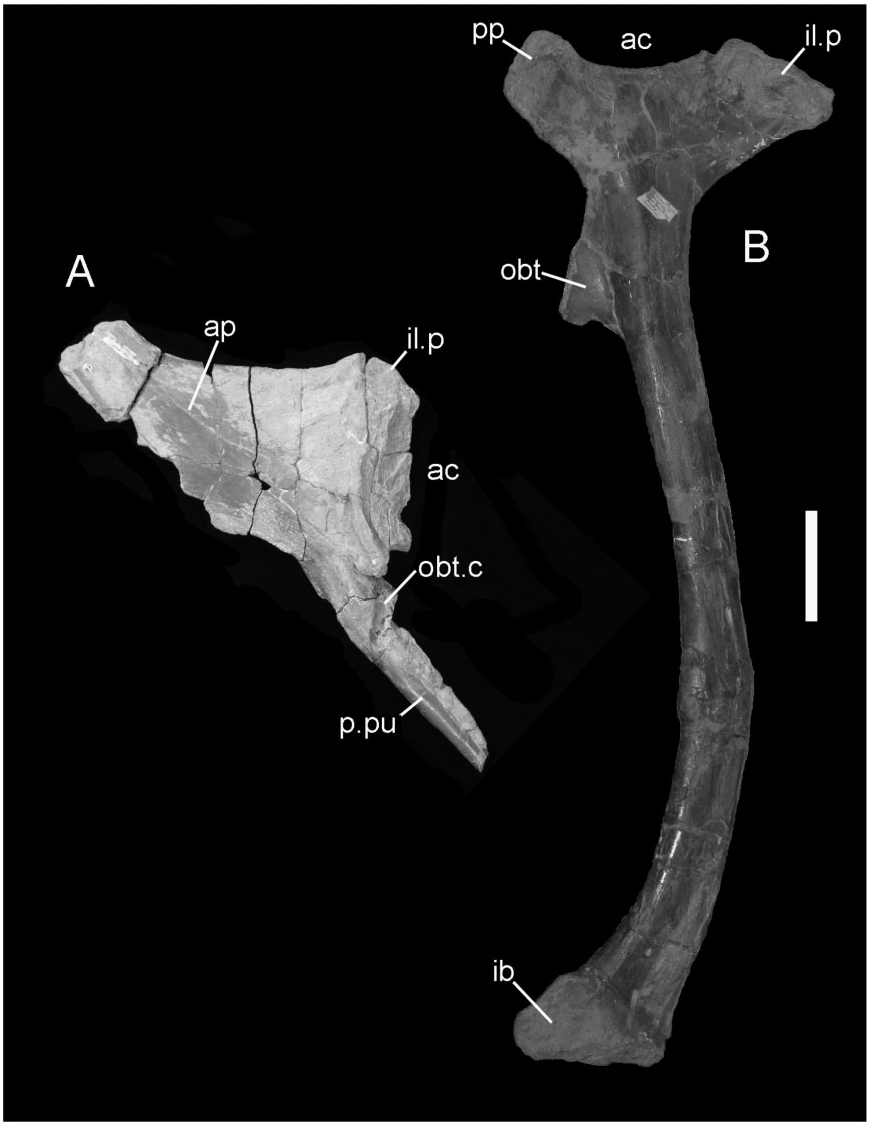

Ilium: This element is represented by a small ( 230 mm long) fragment from the base of the preacetabular process of the left ilium ( Fig. 16 View Figure 16 ). This portion is transversely compressed, curves laterally, and there is a shallow rugose indentation (srf) for the presumed articulation of the sacrodorsal rib, and a low-relief, curved medial ridge (mr). The dorsal edge of the ilium is laterally compressed, flat-topped, and has a band of blisterlike rugae (m.sc) along its dorsolateral edge. Although extremely incomplete, this resembles the corresponding part of NHMUK R1635 (the holotype ilium of Hy. fittoni – Figs 3A, B View Figure 3 , 9 View Figure 9 ) and contrasts markedly with the corresponding region of the ilium of the sympatric contemporary B. dawsoni ( Fig. 3C, D View Figure 3 ).

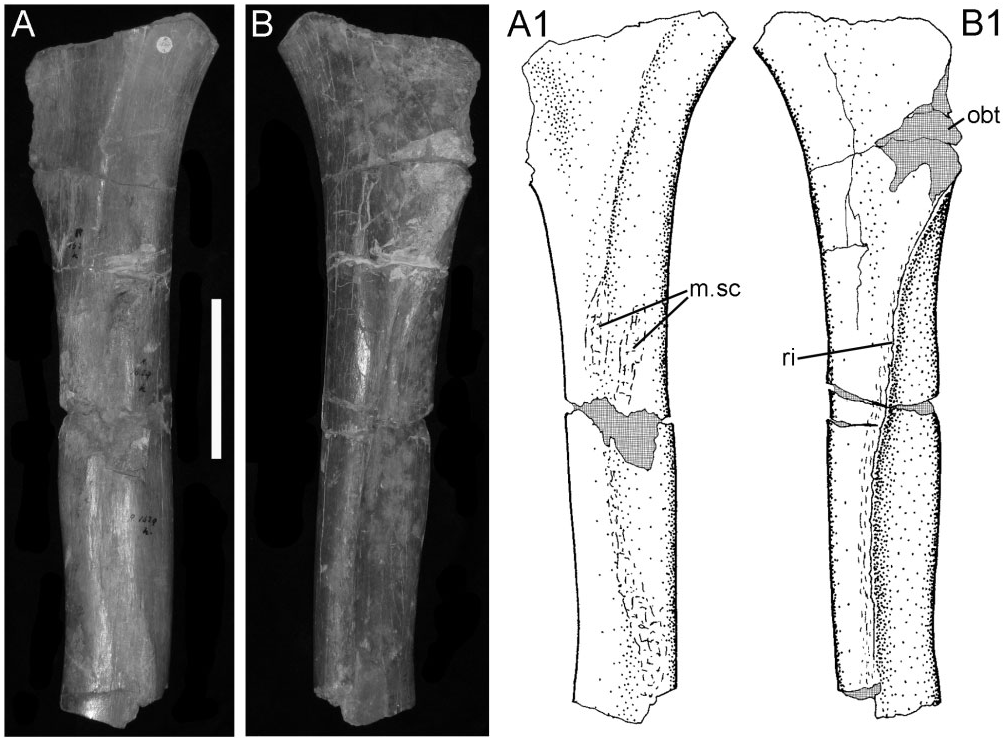

Ischium: The ischium is represented by a part of the shaft ( Fig. 17 View Figure 17 ). This shows the broken base of the obturator process (obt) and an associated curved ridge (ri) that extends distally on the medial side of the shaft (creating the characteristic ‘twist’ to the shaft). The lateral surface of the ischial shaft is marked by some roughened areas (m.sc) that probably represent muscle scars.

Hindlimb elements: These include the undoubted counterpart left femur ( Fig. 18 View Figure 18 ) to that of NHMUK R1148 (cf. Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). The differences in length (NHMUK R1148: 900 mm, NHMUK R1629: 860 mm) reflect the effects of breakage and compression in both specimens. The robust anterior trochanter (at), large, crested fourth trochanter ( 4t), curved, angular shaft, and enlarged distal condyles are well displayed. A poorly preserved proximal portion of the left tibia similarly complements that belonging to NHMUK R1148. A distal end of the right fibula is also preserved.

A well-preserved right metatarsal II ( Fig. 11E–H View Figure 11 ) is transversely compressed proximally; it has a tab-like flap on its dorsolateral edge (tab) and has an obliquely offset distal articular surface that is slightly bicondylar (pulley-like) ventrally ( Fig. 11H View Figure 11 ). It fits snugly against the corresponding surface of the third metatarsal (NHMUK R1148). A well-preserved proximal pedal phalanx (probably pedal digit II – Fig. 11 View Figure 11 I−N) resembles that of left pedal digit II (in comparison with I. bernissartensis and M. atherfieldensis – Norman, 1980, 1986) and articulates snugly with the metatarsal just described.

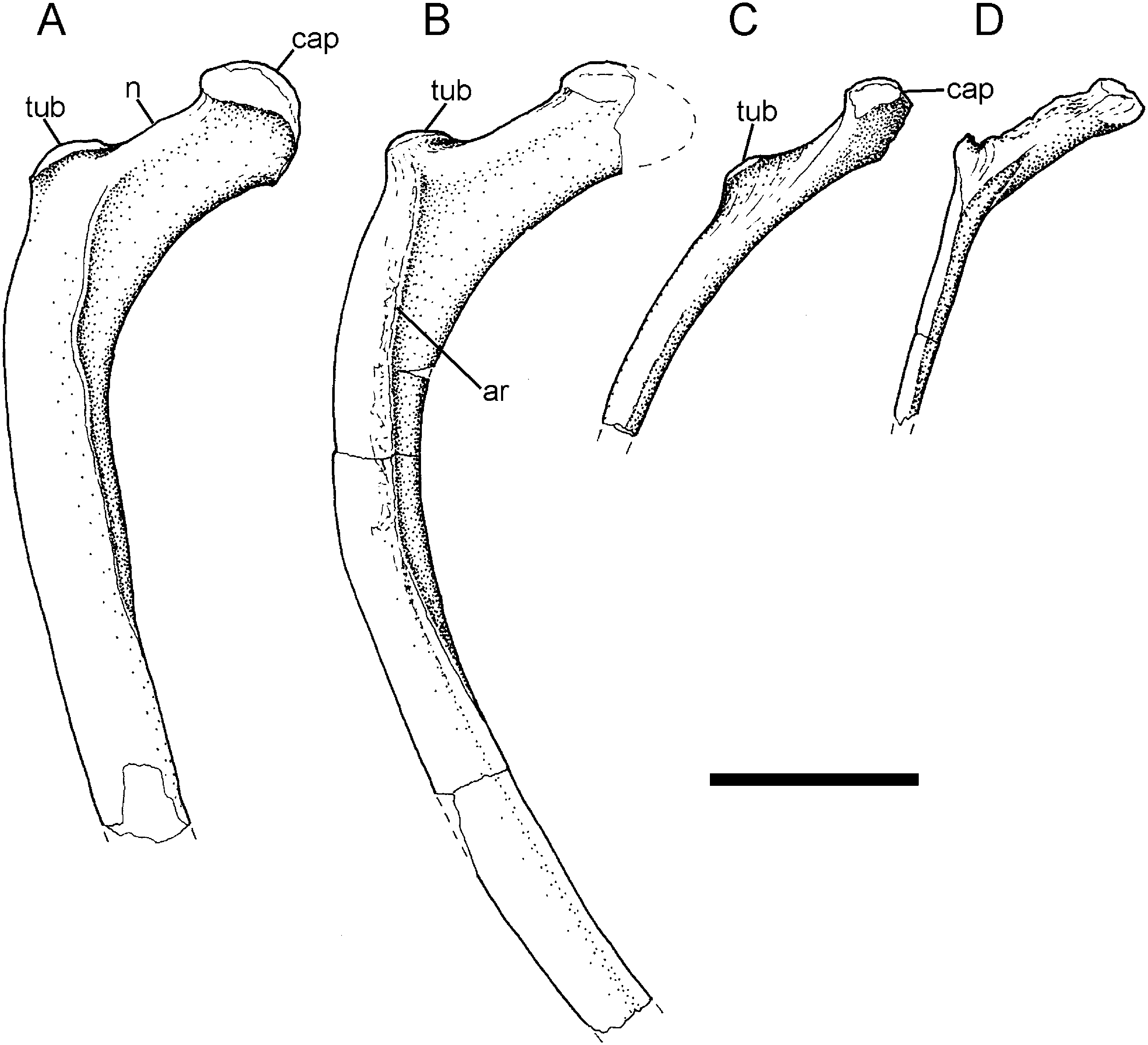

Some rib fragments are preserved in this collection; these include proximal portions that exhibit the wide separation or neck (n) between capitulum (cap) and tuberculum (tub) and angulation between the articular portion and the main shaft of the rib typical of anterior dorsal ribs ( Fig. 25A, B View Figure 25 ). More posterior members of the series ( Fig. 25C, D View Figure 25 ) gradually lose the distinct neck region as the capitulum and tuberculum begin to merge, and the shaft of the rib does not show the strong curvature seen in the anterior dorsal series.

NHMUK R1148 (R1632)

Note. Lydekker (1889) incorrectly identified broken cervical centra as sacrals. No specimens duplicate the holotype and these specimens were collected from the same quarry at ‘a short distance from [NHMUK R1148 and R1629], and almost certainly belong to the same individual’ ( Lydekker, 1890a: 263).

Vertebrae

Cervical vertebrae ( Fig. 19 View Figure 19 ) are mostly badly crushed and sheared, and their neural arches are separated and broken. Individually they retain some characteristic cervical features: strong opisthocoely; thick and rugose ventral keels (k); anteroposteriorly expanded parapophyses (par) close to the margin of the anterior articular condyle and positioned on a lateral ridge on the side of the centrum; broad neural canal; neural arches with no obvious neural spine; long, hooked, divergent postzygapophyses (poz). The prezygapophyses (prz) are widely separated from the midline and the diapophyseal facets (dia) lie above and lateral to the parapophyses.

The dorsal vertebra is a crushed centrum that resembles in size and shape those associated with NHMUK R1148. The sacral vertebra comprises just a centrum (sheared off dorsally) and is somewhat crushed dorsoventrally. It was clearly a sacral, judged by its general shape and remnants of intervertebral sacral rib attachments, but little else can be gleaned. The caudal vertebrae are similarly poorly preserved, having been crushed, distorted, and broken (resulting in loss of the caudal ribs and neural arches). The more anterior in the series tend to have tall centra with subparallel sides, prominent haemal arch facets, and caudal ribs placed adjacent to the neurocentral suture. More posterior caudal centra have a lower profile and more angular sides, with a slight ridge dividing the external surface horizontally, just above midheight. Beneath this ridge, the sides converge upon a keeled area between the haemapophyses (chevron bone facets) that has a midline sulcus. The articular facets are oval and slightly depressed in their upper centre and the posterior haemapophysis is more prominent than the anterior. The posterior caudals are low, angular-sided cylinders with a prominent midline ridge laterally and the ventral surface is flattened, rather than sulcate.

Metatarsal III

Metatarsal III (right) is well preserved, but lacks its proximal half. It closely resembles the left metatarsal III of NHMUK R1148. This specimen is just slightly smaller than the latter (the width of the distal articular surface being 115 vs. 120 mm in R1148) but the details of the surface features are identical.

Phalanges

A manus ungual closely resembles in shape that of digit II of the manus of late Wealden taxa such as Iguanodon ( Norman, 1980) and Mantellisaurus ( Norman, 1986, 2012) in being elongate, but flattened and twisted distally.

| NHMUK |

Natural History Museum, London |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.