Dugong dugon (Muller, 1776)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6598667 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6598634 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/056187C6-FFA3-FFD4-FF73-0CAAF771F391 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Dugong dugon |

| status |

|

French: Dugong / German: Dugong / Spanish: Dugoén

Other common names: Sea Cow, Sea Pig

Taxonomy. Trichechus dugon Muller, 1776 ,

“Vorgeburge der Guten Hofnung an, bis an die philippinischen Inseln” (= Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, to the Philippines).

This species is monotypic.

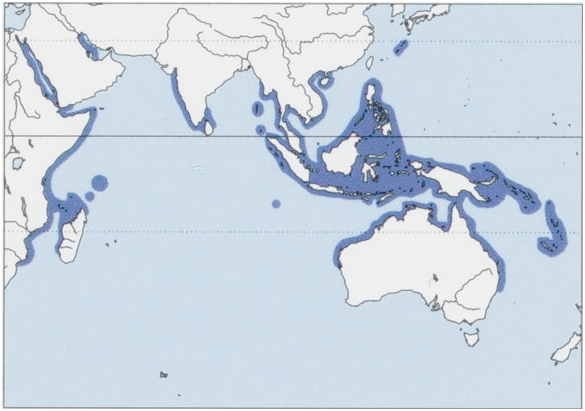

Distribution. Tropical and subtropical coastal and island Indo-Pacific waters (from East Africa to Vanuatu) between c.26-27° N and ¢.25° S. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length 200- 330 cm; weightto at least 570 kg. Neonates 100-113 cm and weight 25-35 kg. Body of the Dugongis fusiform, hindlimbs are absent, tail fluke is whale-like, forelimbs are paddle-like without nails, skin is smooth with sparse hair, and muzzle is directed ventrally terminating in horseshoe-shaped oral disk. Dugongs havelittle sexual size dimorphism. Adults are dark gray dorsally but may appear brownish, especially from an aircraft; they are paler ventrally. Older individuals often have white patches on their dorsal surface and may be extensively scarred. Young are paler than adults. Eyes on either side of head are small, round, and black; eyelids have no lashes and close with sphincter action. There are no external ear pinnae. The complete dental formulais 12/3, C0/1,P 3/3, M 3/3 (x2) = 36, but the anterior pair of upperincisors, lower incisors, and canines are vestigial. Bones are dense and pachyostotic (thickened and solid).

Habitat. Primarily coastal seagrass meadows. Dugongs exploit tidal cycles to access intertidal seagrass meadows.

Food and Feeding. Dugongs are seagrass-community specialists, although they also may eat algae and invertebrates. When feeding on seagrasses with accessible rhizomes, Dugongs excavate the above-ground and below-ground parts of plants by digging up the plants and leave a serpentine feeding trail in the sediment. Dugongs also deliberately eat invertebrates such as burrowing mussels, ascidians, chaetopterid worms, and possibly sea pens, at least in winter in the subtropics.

Breeding. Breeding cycles of Dugongs are diffusely seasonal. Mating structures are variable—single estrous females tended by roving males may form “mating herds.” In addition, lekking has been reported at one location. Males mature at about the same ages as females, 6-17 years. Dugongs usually bear a single young after gestation of c.14 months. Sparse data suggest that lactation can last up to c.18 months, although Dugongs start eating seagrasses soon after birth.

Activity patterns. Dugongs do not have well-defined patterns of circadian activity. Their daily life is ruled by the tidal cycles, which they exploit to access intertidal seagrass meadows. Their need to conserve energy in response to seasonal changes in temperature or food availability also influences diurnal activities, as can hunting pressure or boating activity. Dugongs spend most of their time feeding, traveling, and moving between the surface and the bottom, with relatively little time resting, socializing, or rolling. Time budgets differlittle between single individuals and mothers with young. Nevertheless, mothers spend significantly more time feeding than do their young, presumably because young have access to milk and seagrass.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Movements and home ranges of Dugongs are individualistic. Most individuals make commuting movements between intertidal and subtidal seagrass beds, depending on tidal and diurnal cycles. Some individuals make long-distance movements of up to several hundred kilometers in a few days. There is weak evidence for matrilineal use of space, presumably necessitated by occurrence of large-scale seagrass diebacks, and water temperature at higher latitude limits to their distribution. The only confirmed social unit is a female with her nursing young. Dugongs form herds, but these tend to be transient.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. A crude estimate of the Dugong’s extent of occurrence is 860,000 km?, based on potential available habitat in waters less than 10 m deep within its known distribution. This area spans about 128,000 km of coastline across at least 38, and up to 44, countries and territories. Although the Dugong still occurs at the extremes of its distribution, it is believed to be declining or extinct in at least one-third of its distribution, of unknown status in about one-half its distribution, and possibly stable in the remainder—mainly the remote coasts of parts of tropical Australia. The global population of the Dugong is also much greater than any other extant sirenian, totaling in the tens of thousands in northern Australia alone. Previous regional/subregional assessments of the conservation status of the Dugong were summarized in the United Nations Environment Programme’s 2002 report, Dugong: Status Report and Action Plans for Countries and Territories, and in a supplemental table on The IUCN Red Listin 2012. The Dugong’s distribution is huge and fragmented, ecologically and geopolitically, its regional conservation status changes as new information becomes available. The most recent assessment, published in 2011, considers that the Dugong is critically endangered in Japan, Palau, and the urban coast of Queensland (Australia); endangered in East Africa, the Indian subcontinent and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and continental East and South-East Asia; vulnerable in East and South-East Asian major archipelagoes, Torres Strait between Australia and Papua New Guinea, and the northern Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (Australia); data deficient in Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, Persian Gulf and most of Australia’s northern coastline and the Western Pacific Islands; and least concern only in Shark Bay to North-West Cape (Australia).

Bibliography. Anderson (1981, 1986, 1989, 1997 1998), Anderson & Barclay (1995), André et al. (2005), Aragones et al. (2006), Chilvers et al. (2004), Daley et al. (2008), Domning (1978), Domning & Beatty (2007), Domning et al. (2007), Fitzgerald et al. (2013), Grech & Marsh (2008), Lacépede (1799), Lanyon & Sanson (2006a, 2006b), Lanyon etal. (2010), Marsh (1980, 2008), Marsh & Kwan (2008), Marsh, Channells et al. (1982), Marsh, Heinsohn & Spain (1977), Marsh, O'Shea & Reynolds (2011), Marsh, Penrose et al. (2002), McNiven & Bedingfield (2008), McNiven & Feldman (2003), Preen (1989, 1995), Preen & Marsh (1995), Sheppard, Jones et al. (2009), Sheppard, Marsh et al. (2010), Sheppard, Preen et al. (2006).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.