Mungos mungo, E. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire & F. G. Cuvier, 1795

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5676639 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6581798 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/143F87B3-FFDA-FF9D-FA0C-9FF5F7CAF58E |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Mungos mungo |

| status |

|

34. View On

Banded Mongoose

French: Mangouste rayée / German: Zebramanguste / Spanish: Mangosta rayada

Taxonomy. Viverra mungo Gmelin, 1788 ,

origin uncertain (later attributed to Gambia, but subsequently suggested to be Cape Province, South Africa).

Up to fifteen subspecies have been named, but a revision is needed.

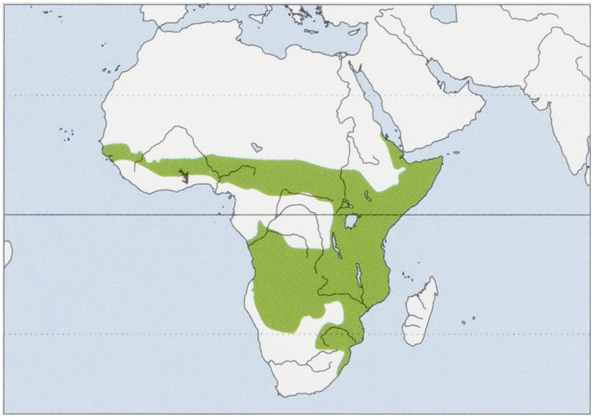

Distribution. Senegal and Gambia E to Eritrea and Somalia and then SW to PR Congo, Angola, and NE Namibia, and S to E South Africa. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 30-40 cm (males), 33-38. 5 cm (females), tail 17.8-31 cm (males), 19-245 cm (females), hindfoot 5.3-9 cm (males), 5.3-8. 4 cm (females), ear 2.1-3. 6 cm (males), 2.2-7 cm (females); weight 0-89.1-88 kg (males), 0-99.1-74 kg (females). No obvious sexual dimorphism. Medium-sized; body covered with coarse hair. Coat color varies geographically from whitish-gray to dark brown, with 10-15 dark bands across the back from the shoulders to the base of the tail. The guard hairs are short on the head ( 6 mm), lengthen toward the rump ( 45 mm in eastern specimens, 35 mm in western specimens), and are shorter on the tail. The individual guard coat hairs are light-colored at the base, with two broad black bands interspersed with light bands and a narrow dark tip. In reddish-brown mongooses, the lighter-colored bands are red-brown. The underfuris fine and short, with a dark base and light tip; there is apparently no undercoat on the rear. Long head with a pointed muzzle. Rhinarium short and lacks split. Ears small and rounded. Five digits on foreand hindfeet; hallux and pollex reduced. Front claws are elongated ( 20 mm —exceptfirst digit, which is 8 mm) and strong for digging. Hindclaws shorter ( 14 mm) and less curved than front claws. Three pairs of mammae. Pear-shaped braincase. Postorbital bars incomplete. Zygomatic arches thin. Short, broad rostrum. Supraoccipital crest not well-developed (less than 1-5 mm high). No sagittal crest. Dental formula: 13/3, C1/1,P 3/3, M 2/2 = 36. Sharp strong teeth, especially canines. Outer incisors larger than inner. Upper canines slightly recurved. Lower canines distinctly recurved. Cheek teeth possess low, rounded cusps. Carnassials adapted to crushing, not slicing.

Habitat. Found in a wide range of habitats, principally in savannah and woodland. Also seen in towns and villages. Absent from desert, semi-desert, and montane regions. Preferentially use termitaria as dens; otherwise dens are sited in gulleys or thickets. Dens have multiple entrances and chambers.

Food and Feeding. Insectivorous diet, especially Coleoptera (beetles) and Myriapoda (centipedes) larvae. Occasionally vertebrates (including eggs, mice, rats, frogs,lizards, and small snakes) are consumed. Frequency of occurrence of food types in 120 scats from Uganda: Diplopoda (96%), Coleoptera (88%), Formicidae adults (69%) and pupae (23%), Gryllidae (44%), Isoptera (33%), Dermaptera (23%), larvae (unidentified) (20%), Blattidae (13%), Acrididae (10%), Acarina (8%), pupae (unidentified) (7%), Hemiptera (6%), Tettigoniidae (5%), Lepidoptera (2%), Araneae (3%), and Gastropoda (2%). Frequency of occurrence of food types in 113 scats from Natal ( South Africa): Myriapoda (70%), Coleoptera (92%), Orthoptera (57%), Isoptera (33%), Hemiptera (29%), Arachnida (21%), Seeds (20%), Mammalia (7%), Lepidoptera (7%), and Blattodea (5%). Frequency of occurrence of food types in 14 stomachs from Zimbabwe and Botswana: Insecta (71%), Reptilia (43%), fruits (36%), Amphibia (7%), Araneae (7%), Myriapoda (7%), Scorpiones (7%), and Solifugae (7%). Human garbage dumps also utilized. Banded Mongooses move as a group, but individuals forage independently within the moving group. Individuals generally walk, sniffing and scraping at the ground, and often stop and dig intensively for prey. Dung of large herbivores (especially African Elephant, Loxodonta africana) is popular for foraging, due to the relatively high density of beetles. Individuals often crack hard-shelled prey (e.g. dung beetle, pill millipede, or egg) by holding it in their front paws, whilst balancing on their hindlimbs, and throwing it between the hindlegs onto a rock or other hard surface. Prey and foraging sites such as holes, scrapes, and dung are generally defended from conspecifics, except for adults provisioning or sharing food with young pups. There is a report of a group stealing food regurgitated by a pair of Black-backed Jackal for their pups.

Activity patterns. Diurnal. Groups sleep together in subterranean dens, emerging in early morning and returning before sunset. During the day the group forages together, usually resting in a shady area around midday. The behavioral repertoire includes foraging, resting, vigilance (including standing on the hindlegs), self and allogrooming, social play, scent marking, and vocalizing.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Banded Mongooseslive in cohesive groups, which share a home range. In Uganda (Queen Elizabeth National Park), mean group size is 15 individuals (range = 9-28), mean home range size is 0-9 km* (range = 0-6-2), mean population density is 18 individuals/km?* (range = 7-36), and daily foraging distances are 2-3 km. In Tanzania (Serengeti), mean group size is 15 (range = 4-29), mean population density is two individuals/km?, and daily foraging distances are up to 10 km. A group size of 41 was recorded in Somalia, and 75 from South Africa (Kruger National Park). Group size, home range size, population density, and daily foraging distances depend upon habitat type and food density, and therefore vary geographically. Groups have up to 40 dens within their home range. They generally occupy a different den every few days, but use a den for longer periods when babysitting pups. Concentrated food sources (e.g. garbage dumps) can support larger groups and smaller core areas within the home range. Home ranges are defended. A smaller group will generally retreat, without physical aggression, but skirmishes can occur and individuals have been killed during such encounters. Groups respond more intensely to scats of neighboring groups than to scats from more distant groups, suggesting that neighbors pose a greater threat. Groups are highly social. Grooming and marking maintain group bonds. Groups contain adult males and females and their young. The adult sex ratio is male-biased. Within a group, males are closely related and females are closely related, but the breeding adults are not related to each other. There is generally little evidence of a dominance hierarchy. However, a male dominance hierarchy becomes obvious during estrus, when males compete for access to females. Aggression over food items is usually settled in favor of the owner. Group members cooperate in rearing young and repelling predators; one group was seen rescuing a member from the talons of a martial eagle. One case of invalid care has been reported. Group members communicate vocally. Contact calls, emitted every few seconds, serve to maintain group cohesion while foraging. “Lead” calls are used by individuals to elicit the group to follow them; “pup-follow” calls encourage pups to follow the adults. Shrill chirruping “war” cries alert group members to a rival group and encourage them to charge at the invaders. Growls and spits are used to defend resources if another group member approaches. Short, sharp alarm calls elicit rapid evasive behavior; “worry” calls warn group members of lower-intensity danger. A “lost” call indicates distress when an individualis separated from the group. Individuals also respond to the alarm calls of other species, in particular plover ( Vanellus spp.). Olfactory communication is also used in intraand inter-group communication. Group members scent-mark each other and objects (e.g. rocks), by wiping them with the anal gland. This marking is often done communally, with all group members involved in an orgy of scent marking. Urine and feces are also apparently used in communication, with individuals overmarking excretion sites. An olfactory “signal” from another group often elicits an excited and aggressive response. In addition to allogrooming, Banded Mongooses in Uganda and Masai Mara, Kenya, have been seen grooming Common Warthogs ( Phacochoerus africanus); they are probably removing ectoparasites, which they eat.

Breeding. In seasonal climates, births are restricted to the wetter months (presumably correlated with invertebrate prey availability). Females in dry regions have one or two litters a year; females in wetter equatorial regions can have up to five. The age at which females first reproduceis also geographically variable, recorded at two years in the Serengeti and under one year in Uganda (the earliest record being just over eight months). Estrus can occur within six days of parturition, enabling females to conceive and gestate while suckling the current litter of pups. This minimizes the interbirth interval, so females can produce four or even five litters per year. During estrus, males compete for access to females. Dominant males guard females and aggressively repel subordinate males who attempt to sneak copulations. There is no sign of female competition for access to males. However, there is a hierarchy in mate-guarding, with older females mate-guarded first, and younger females mate-guarded later. Each female is guarded for two to three days. Females may escape their mate-guard and mate with other males within and outside their group. The overall result is that most males and females copulate with numerous partners. About 75% of the females in a group give birth. Gestation lasts approximately nine weeks. Mean litter size is 3-2 (range = 1-6). Litter size and fetus size are smaller in younger, smaller females. Abortion and miscarriage are rare. Banded Mongooses are truly communal breeders, with up to ten females in a group giving birth, often on the same day, in the same den (there is rarely more than a few days between births). Such birth synchrony may reduce infanticide by reducing the ability of males and females to discriminate between offspring. Although infanticide occurs, it appears to be a rare event. Alternatively, synchronous parturition may be a strategy to economize pup care, by enabling communal care of the young for a minimal period. A female may either abort her litter or give birth to it over different days—an extremely unusual behavior for a mammal. Birth weight of pups is 20-50 g. Pups are born blind and with short fur. Their eyes open at around ten days. The sex ratio of pups at emergence from the den is male-biased. Pupsstay in the subterranean den until they are weaned, at around three to four weeks of age. During this period, one or more individuals will remain at the den to “babysit” the pups while the group forages. The babysitter usually changes every day. These babysitters guard the communal litter against predators. On the rare occasions when pups are observed out of the den during this period, pups suckle from numerous females. When the pups emerge from the den and begin accompanying the foraging group, adults provide care by carrying, grooming, playing with, and provisioning pups. Provisioning involves dropping or leaving whole or partial prey items. Adults also provide protection: pups shelter under the belly of the nearest adult when frightened. Most pups have an adult escort, who cares forit for four to eight weeks; this escort is unlikely to be the pup’s parent. The pup closely followsits escort, fending off other pups, and begging for the food items the escort provides. Pups that associate most often with an escort are more likely to survive. Males generally do more babysitting and escorting than females. Due to their relatively small body size, open habitat, and diurnallifestyle, pups and adults are vulnerable to a wide array of predators. In Uganda, pup mortality is high, with 20% of litters failing completely within the first month. Only 18% of pups are estimated to survive from birth to independence. Adult survival is substantially higher (annual survival rate 0-86). Comparable annual survival rates from Serengeti are 0-46 for pups and between 0-65 and 0-69 for adults. Pups are heavily preyed upon by marabous ( Leptoptilus crumeniferus) and Nile monitors ( Varanus niloticus); predators on adults include snakes (especially the rock python Python sebae), mammalian carnivores (e.g. Leopards) and raptors (e.g. martial eagle). Dispersal can occur via forced eviction of single-sex sub-groups by group members or via voluntary emigration (also of single-sex sub-groups). Dispersers are usually young adults. There is no clear sex bias to dispersal, although females appear to be evicted and males appear to voluntarily emigrate more often. Banded Mongooses can live to over ten years in the wild, and twelve years in captivity.

Status and Conservation. Not CITES listed. Classified as Least Concern in The IUCN Red List. As a species with wide habitat tolerance and distribution, and one that adapts well to human habitation, itis unlikely to become threatened in the foreseeable future.

Bibliography. Bell (2007), Cant (1998, 2000, 2003), Cant & Gilchrist (In press), Cant et al. (2001, 2002), Caro & Stoner (2003), De Luca & Ginsberg (2001), Eisner (1968), Eisner & Davis (1967), Estes (1991), Gilchrist (2001, 2004, 2006a, 2006b, 2008), Gilchrist & Otali (2002), Gilchrist & Russell (2007), Gilchrist et al. (2004, 2008), Hiscocks & Perrin (1991a, 1991b), Hodge (2003, 2005), Kingdon (1971-1982, 1997), Masi et al. (1987), Messer (1983), Muller (2007), Muller & Manser (2007), Neal (1970a, 1970b, 1971), Otali & Gilchrist (2004), Rood (1974, 1975, 1983b, 1986), Simpson (1964, 1966), Skinner & Chimimba (2005), Smits van Oyen (1998), Van Rompaey (1978), Viljoen (1980), Waser et al. (1995), Wozencraft (2005).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.