Peridinetus Schönherr

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.195971 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6208875 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/1A672222-FFF2-C268-FF75-190FFBACFABE |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Peridinetus Schönherr |

| status |

|

Peridinetus Schönherr View in CoL

Peridinetus Schönherr, 1837: 467 View in CoL . Type species: Curculio irroratus Fabricius, 1787 View in CoL , by original designation.

Peredinetus [lapsus]. Chevrolat (1880: 38).

Peridenetus [lapsus]. Fiedler (1932: 83), Hustache (1949: 13).

Peridinetuus [lapsus]. Hustache (1949: 17).

Ephimerus Schönherr, 1843: 331 . Type species: Ephimerus sexguttatus Boheman, 1843 View in CoL (= Curculio sexguttatus Fabricius, 1775 View in CoL ), by original designation. Prena (2009b: 54) [synonymy].

Phelambates Jekel, 1883: 84. Type species: Peridinetus sanguinolentus Chevrolat, 1883 View in CoL , by indication. Wibmer & O’Brien (1986: 279) [implied synonymy with Peridinetus View in CoL based on placement of type species in Hustache (1938); however, Phelambates was overlooked therein], Alonso-Zarazaga & Lyal (1999: 103) [synonymy with Peridinetus View in CoL accepted].

Conophoria Casey, 1922: 9 View in CoL . Type species: Peridinetus distinctus Pascoe 1880 View in CoL , by original designation. New synonymy.

Peridinetus (Conophoria) View in CoL . Hustache (1938: 8).

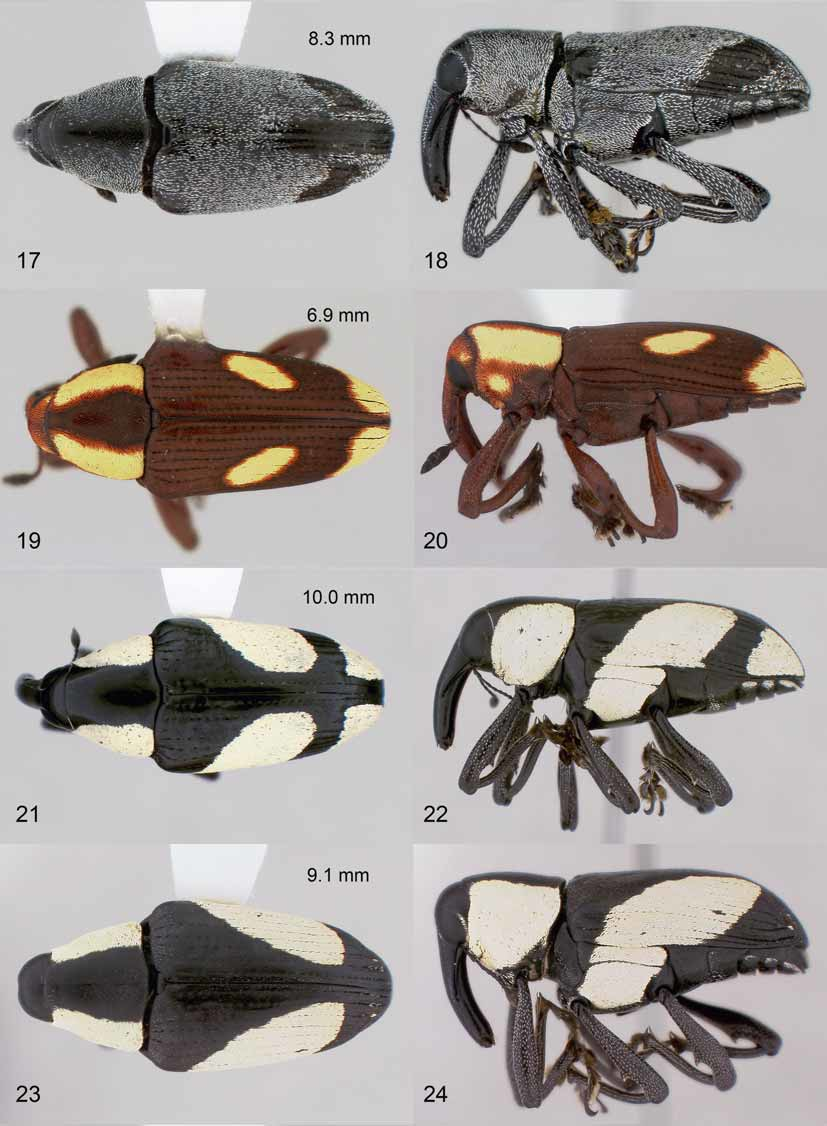

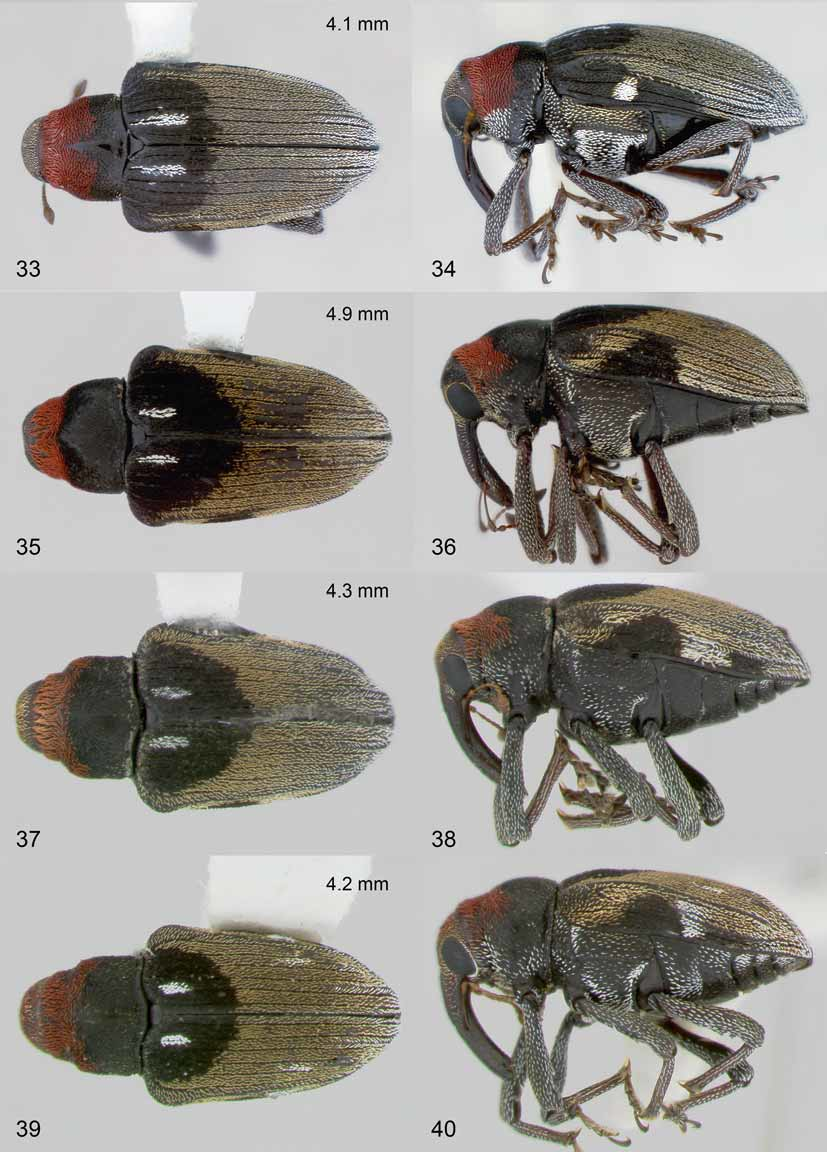

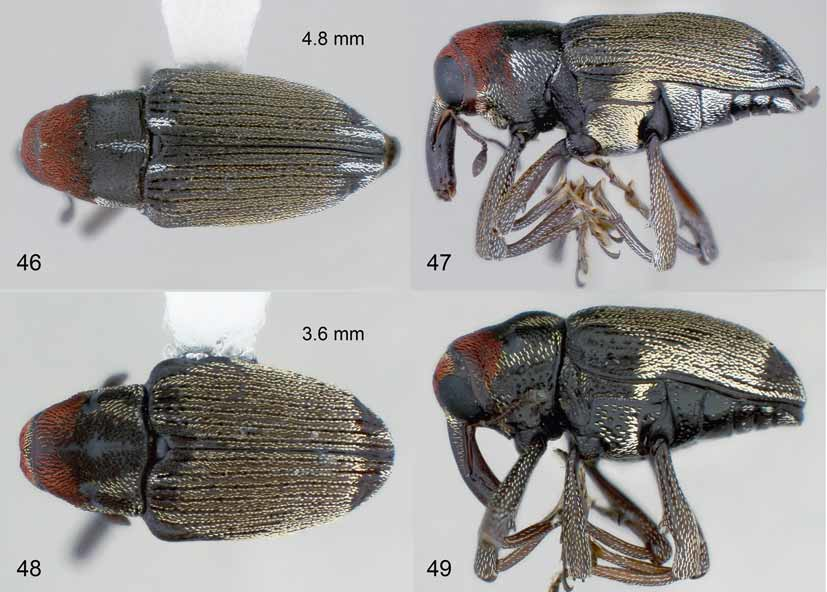

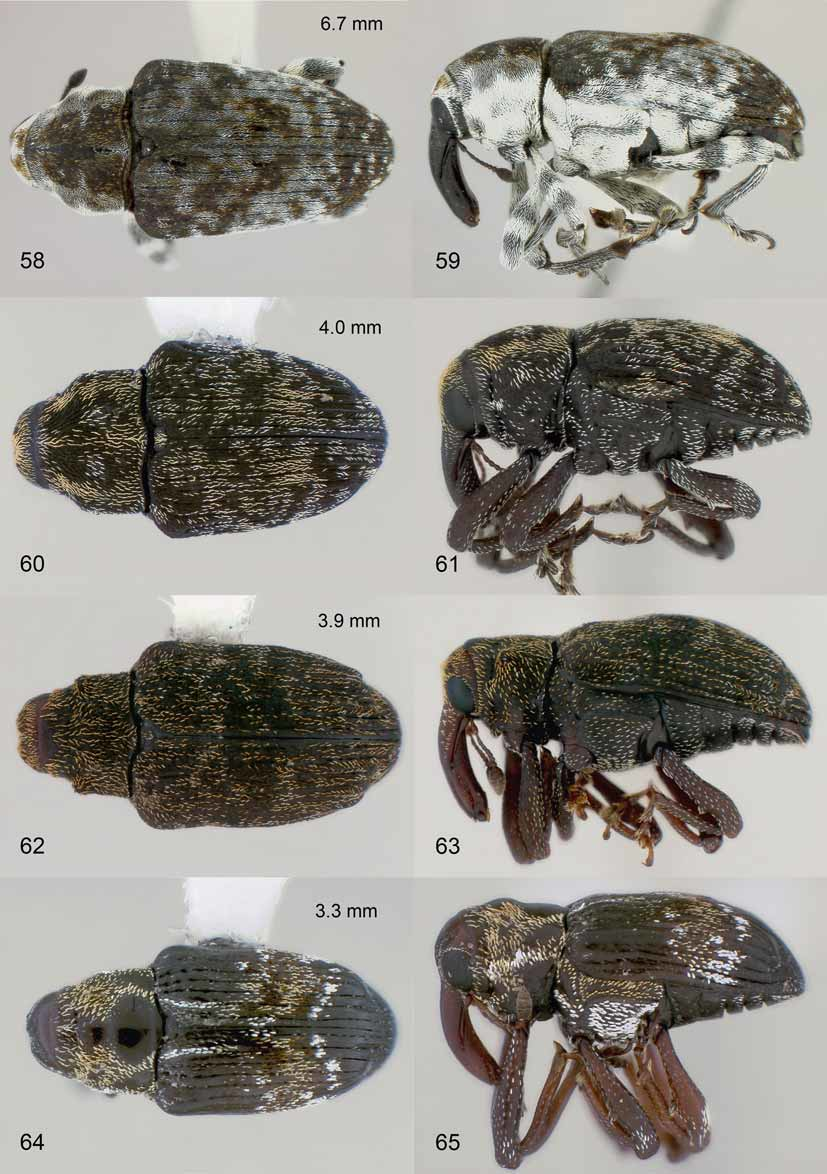

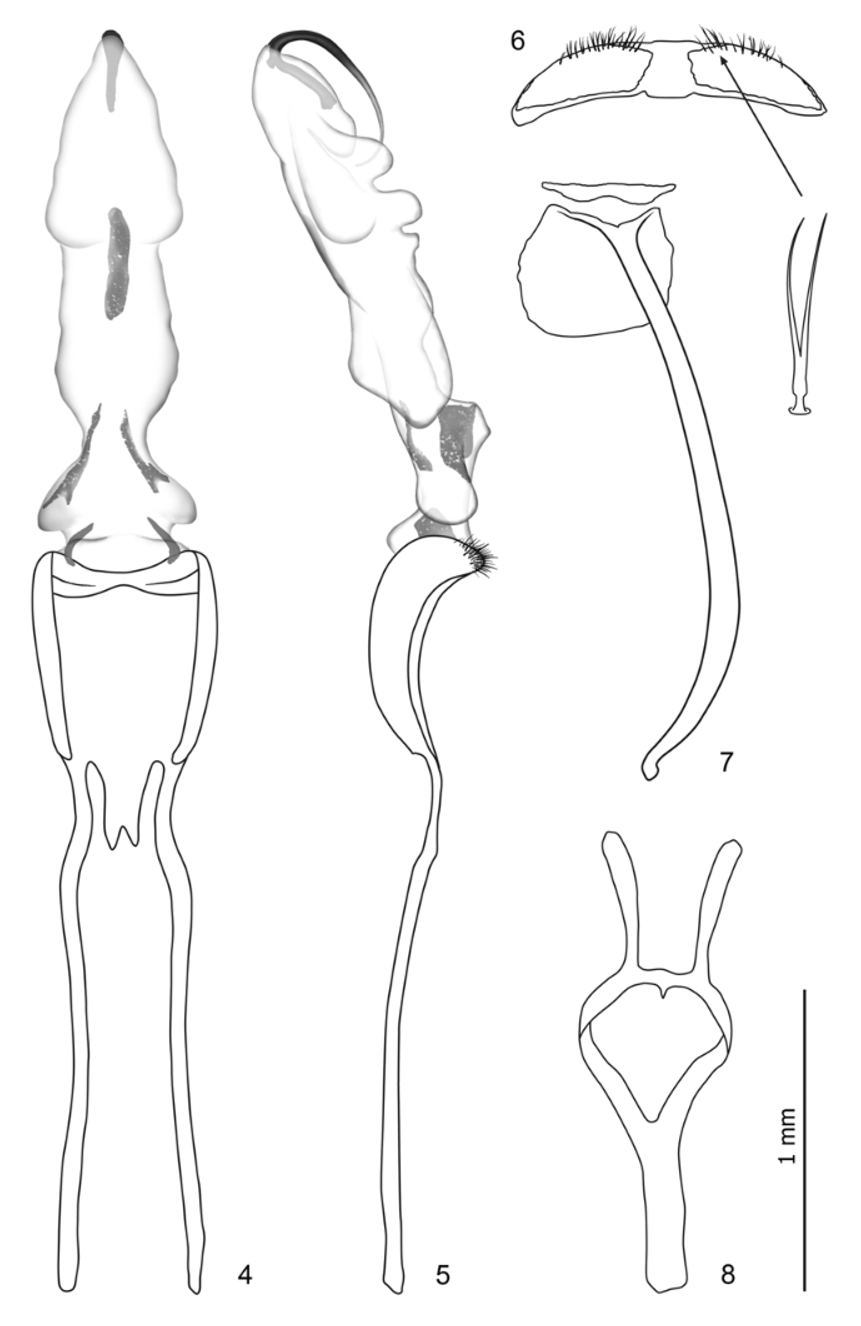

Diagnosis. Peridinetus belongs to a moderately diverse group (ca. 400 species) of predominantly Neotropical weevils, which have a ventral tooth on at least the meso- and metafemora and the pygidium covered by the elytra. This group includes several described and undescribed genera with a distinct prosternal channel and separate procoxae. In Middle America, Peridinetus includes all species with this type of prosternum, basally subconnate claws and a rather thick, cylindrical rostrum, which generally is wider than the frons. The body shape varies from ovate to subtriangular ( Fig. 11–40 View FIGURES 9 – 16 View FIGURES 17 – 24 View FIGURES 25 – 32 View FIGURES 33 – 40 , 46–65 View FIGURES 46 – 49 View FIGURES 50 – 57 View FIGURES 58 – 65 ) and the total length from 2.5–11.5 mm. The closely related genus Palliolatrix Prena differs in having the eyes smaller and more widely separated, the rostrum less cylindrical, the antenna inserted more distally on the rostrum and the scrobes more descending. The male genitalia of Peridinetus species are remarkably uniform, with the body of the aedeagus almost square and the internal sac long ( Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 – 8 ). The distal part of the duct is a relatively short, sclerotized tube ( Fig. 5 View FIGURES 4 – 8 ), whereas it is flagelliform and much longer in Palliolatrix . Peridinetellus subnudus Champion has a glabrous surface, subcylindrical prothorax ( Fig. 9 View FIGURES 9 – 16 ) and slightly more elongate aedeagus, but otherwise seems to share with Peridinetus most morphological character states; the validity of this generic name should be reassessed in connection with an undescribed Ecuadorian species near P. subnudus .

Distribution. Species of Peridinetus have been found in Middle America, the immediately adjacent parts of North America (i.e., Veracruz in Mexico) and the Greater Antilles. In South America, species have been found south to Ecuador on the Pacific side and south to Bolivia and Brazil on the Atlantic side. They inhabit moderately dry to very moist situations, from sea level up to 3000 m elevation.

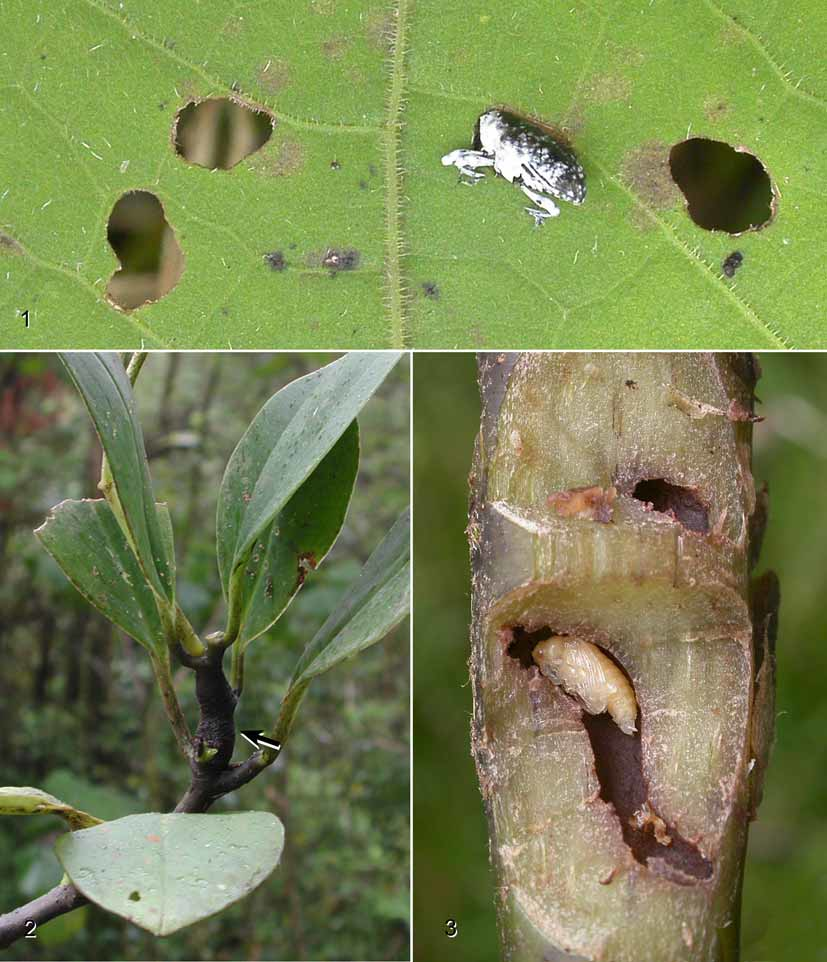

Biology. Adults usually feed on a more or less broad spectrum of species of Piperaceae , especially the genus Piper . Larvae of P. ecuadoricus Casey , P. melastomae Champion and P. zinckeni Rosenschöld have been found tunneling the stem and petiole of Piper species ( Bondar 1943; Stockwell, pers. comm.; Prena, unpubl. observations); P. wyandoti Prena has been reared from the stem and petiole of two Peperomia species (Branstetter, Nishida, Prena, unpubl. observations). The larvae differ morphologically from those of Embates and Pardisomus in having the anus subterminal and the caudal segments less modified ( Prena 2003b, 2005). Their development seems to last one year or longer even for the small species (Nishida, pers. comm.; Prena, unpubl. observations). Pupation takes place inside the plant. The adults can be found throughout the year. As with other Piper -feeding species in the Ambatini and Cyrionychini, they often rest in holes made in the leafblade ( Fig. 1 View FIGURES 1 – 3. 1 ), thereby exposing their flank and imitating parts of plants or excrement ( Bondar 1943, 1949; Jolivet 1994; Monteiro 1998; Prena 2005).

Color pattern. Several species treated herein have amazingly similar color patterns. These are matched not only by unrelated weevils, particularly in the Baridinae , Conoderinae and Molytinae , but also by flies, bees, ants and various other beetles. For example, Hespenheide (1973) found insects with red anterior, black median and grey to yellow posterior areas in five families, 21 genera and 60 species north of South America and more elsewhere (see Fig. 31–49 View FIGURES 25 – 32 View FIGURES 33 – 40 View FIGURES 41 – 45 View FIGURES 46 – 49 for species of Peridinetus ). He considered this a case of mimicry and speculated that certain fast-flying flies served as a model. Several such mimicry complexes have been recognized in the beetle literature ( Lindsley 1959, 1961; Hespenheide 1995) and numerous examples can be found among the Baridinae associated with Piperaceae . I concur with Hespenheide that these color patterns are convergent and without phylogenetic value. It is not rare that morphologically similar (and probably closely related) species have developed completely different strategies for predator avoidance. For example, cryptic coloration occurs in P. irroratus (Fabricius) and P. frontalis Chevrolat , while P. i m p e r i a l i s Prena and P. laetus Champion exhibit bright colors that may deceive or warn potential predators about the weevil’s identity and edibility. However, unlike most Conoderinae , Peridinetus species (and other Baridinae associated with Piperaceae ) are relatively unwary; when approached they typically drop to the ground rather than flying away. This behavior does not support well their classification as Batesian mimics of fast-flying insects, as novice predators should soon find out about this resource. On the other hand, the stringent aroma of the consumed host plant may render the weevil unpalatable and this could be signaled by bright colors. Whether or not this is the case and the evolution of convergent color patterns in some Peridinetus species is driven by Müllerian mimicry, remains speculative. It is also possible that convergent color patterns are the result of convergent crypsis wherein the weevils (and possibly other insects) are imitating some plant part. The phenomenon of similar color patterns in unrelated species (called mimetic homoplasy by Hespenheide 2005) can be complicated further by the presence of poorly differentiated species complexes. A good example is the P. sanguinolentus species complex, where two synapomorphies (plumose setae in the prosternal channel and presence of a dorsal groove on the female rostrum) indicate a close relationship between P. illabes , P. l a e t u s, P. p e n a, P. sanguinolentus and P. wyandoti , while the color patterns of P. coccineifrons , P. imperialis and P. rufotorquatus seem to have evolved independently. Very similar color patterns occur also in Pteracanthus smidtii (Fabricius) and Sympages egregius (Pascoe) , which are not associated with Piperaceae .

Discussion. Jekel (1883) and Casey (1922) proposed new generic names for a few, seemingly aberrant species without having examined representative material of the entire group. Although their reasoning is not entirely unjustified when applied to a subjectively selected set of species, a satisfying and sufficiently robust concept for the grouping of all described and undescribed species is difficult to accomplish. With the exclusion of Palliolatrix and the South American P. incisicollis Hustache and P. suturalis Chevrolat , which may not be congeneric, the most aberrant species of Peridinetus occur in the Greater Antilles, i.e., one complex with a higher degree of sexual dimorphism and another with basally separate tarsal claws. The validity of the currently monospecific Peridinetellus Champion ( Fig. 9 View FIGURES 9 – 16 ) needs to be reassessed in connection with the South American fauna, where at least one other, still undescribed species of this complex occurs. Conophoria Casey was described to accommodate species with a conical pronotum and usually distinct color pattern. However, the pronotum exhibits gradual rather than discrete shapes and the shapes do not correlate with the color pattern. Even though I have used the shape of the pronotum in the first couplet of the key, in combination with the carination of the interstriae, this criterion separates very closely related weevils, such as P. i r ro r a t u s (Fabricius) and P. j e l s k i i Chevrolat or P. lateralis Champion and P. melastomae Champion. Hustache (1938) placed Conophoria as a subgenus of Peridinetus and was followed therein by O’Brien & Wibmer (1982), Wibmer & O’Brien (1986), Alonso-Zarazaga & Lyal (1999) and Prena (2009b). However, Bondar (1949) claimed Conophoria was monotypic and accepted its generic rank. Because Conophoria lacks a meaningful concept and general acceptance, it is placed here in synonymy with Peridinetus . Piazambates Voss , originally described in the Peridinetini, was synonymized with Pardisomus Pascoe by Prena (2003b). Not included in this study is one undescribed, morphologically isolated species near Peridinetus (INBC, JPPC, USNM) known by a few specimens collected from the inflorescence of Piper species in Costa Rica; it is part of a complex that stands in conflict with the current tribal classification of the Baridinae . Also not included herein are the small species near Cyrionyx oblongoguttatus Champion , which morphologically approach Peridinetus but have basally separate claws and lack a frontal fovea.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Peridinetus Schönherr

| Prena, Jens 2010 |

Peridinetus (Conophoria)

| Hustache 1938: 8 |

Conophoria

| Casey 1922: 9 |

Ephimerus Schönherr, 1843 : 331

| Prena 2009: 54 |

| Schonherr 1843: 331 |

Peridinetus Schönherr, 1837 : 467

| Schonherr 1837: 467 |