Scarabaeolus

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3726987 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CF6C1B9C-2EC0-4220-BED7-6402A6C9D175 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3730343 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/1E76DE47-FFE6-3128-52FA-FAECEF0FFB70 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Scarabaeolus |

| status |

|

Review of the Subgenus Scarabaeolus

The list below shows the species deemed by us to belong in the subgenus Scarabaeolus , their type repositories, who first included them, and figures at the end of this paper. Bth = Balthasar, DD = Davis and Deschodt/Deschodt and Davis (in Deschodt et al. 2015); [1] and [2] = numbers of mesotibial spurs; * = on permanent loan to TMSA. Full names of all authors appear in the following Species Accounts.

anderseni Wth. View in CoL [2] BMNH Deschodt et al. 2015 Fig. 72 View Figures 72–80

andreaei View in CoL zur Str. [1] SAMC Deschodt et al. 2015

bohemani Har. [1] MNHN Deschodt et al. 2015 Fig. 43–46 View Figures 39–46

canaliculatus Fm. View in CoL [2] MNHN Ferreira 1972 Fig. 73 View Figures 72–80 , 92–93 View Figures 88–104

carniphilus View in CoL DD [2] TMSA Deschodt et al. 2015

clanceyi Fer. View in CoL [1] DMSA Ferreira 1972 Fig. 65 View Figures 63–71 , 103 View Figures 88–104

cunene View in CoL sp. n. [2] TMSA this paper Fig. 33–38 View Figures 33–38

damarensis Js. View in CoL [2] MNHN Ferreira 1972 Fig. 75 View Figures 72–80 , 95 View Figures 88–104

ermienae View in CoL DD [1] TMSA Deschodt et al. 2015

flavicornis (Boh.) [2] NHRS Ferreira 1972 Fig. 5–8 View Figures 1–8

fragilis View in CoL sp. n. [1] TMSA this paper Fig. 25–28 View Figures 25–32

fritschi Har. [2] MNHN? Deschodt et al. 2015 Fig. 74 View Figures 72–80 , 87 View Figures 81–87 , 94 View Figures 88–104 funebris (Boh.) View in CoL [1] NHRS this paper Fig. 63 View Figures 63–71 , 102 View Figures 88–104

gilleti Js. View in CoL [2] ISNB Ferreira 1972 Fig. 76 View Figures 72–80 , 96 View Figures 88–104

gracai Fer. View in CoL [2] MHNM* Ferreira 1972 Fig. 78 View Figures 72–80

inoportunus Fer. View in CoL [2] TMSA Ferreira 1972 Fig. 82 View Figures 81–87 , 104 View Figures 88–104

inquisitus Pér. View in CoL [2] SAMC Ferreira 1972

intricatus (Fab.) View in CoL [2] ZMUC Ferreira 1972 Fig. 81 View Figures 81–87 , 100 View Figures 88–104

karrooensis View in CoL zur Str. [1] NHMB Deschodt et al. 2015 Fig. 66 View Figures 63–71 , 90 View Figures 88–104

knobeli Fer. [1] TMSA Ferreira 1972 Fig. 21–24 View Figures 17–24

kochi Fer. [2] TMSA Ferreira 1972 Fig. 79 View Figures 72–80 , 98 View Figures 88–104

krugeri View in CoL sp. n. [2] TMSA this paper Fig. 1–4 View Figures 1–8

kwiluensis Js. View in CoL [2] MRAC Barbero et al. 1998 Fig. 77 View Figures 72–80 , 97 View Figures 88–104

laevifrons Fm. View in CoL [2] MNHN Ferreira 1972 Fig. 84 View Figures 81–87 , 91 View Figures 88–104

lizleri View in CoL sp. n. [2] TMSA this paper Fig. 9–12 View Figures 9–16

lucidulus (Boh.) View in CoL [2] NHRS Ferreira 1972 Fig. 83 View Figures 81–87 , 101 View Figures 88–104

megaparvulus View in CoL DD [2] TMSA Deschodt et al. 2015 Fig. 59–62 View Figures 55–62

namibensis View in CoL sp. n. [2] TMSA this paper Fig. 17–20 View Figures 17–24

niemandi View in CoL DD [2] TMSA Deschodt et al. 2015

nitidus View in CoL DD [1] TMSA Deschodt et al. 2015

obsoletepunctatus Bth [1] NMPC Deschodt et al. 2015 Fig. 67–68 View Figures 63–71

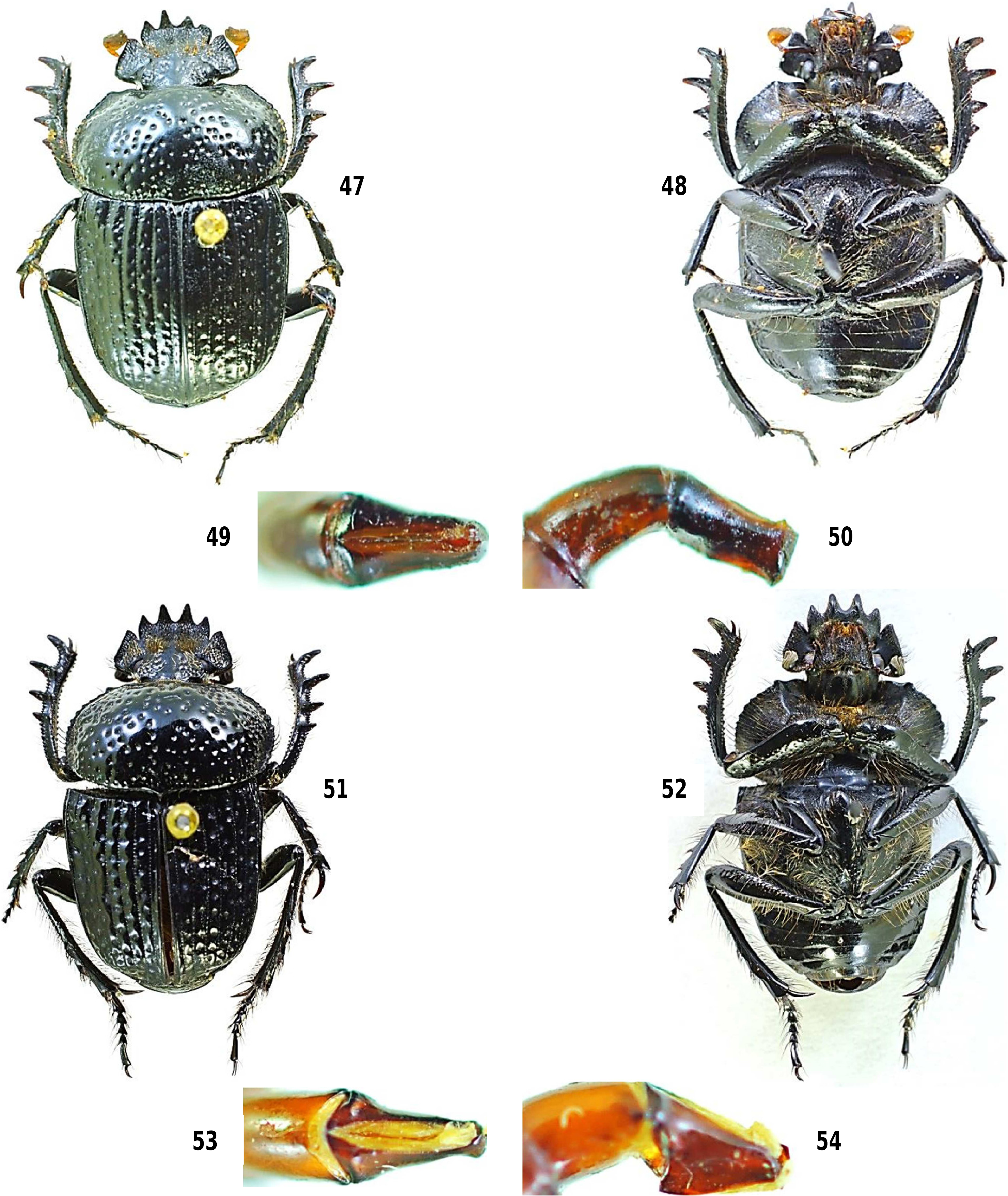

orientalis View in CoL sp. n. [1] TMSA this paper Fig. 47–50 View Figures 47–54

pabulator Pér. View in CoL [2] SAMC Ferreira 1972 Fig. 80 View Figures 72–80 , 99 View Figures 88–104

palemo Oliv. View in CoL [1] MNHN Barbero et al. 1998 Fig. 69–70 View Figures 63–71 , 88 View Figures 88–104

parvulus (Boh.) View in CoL [1] NHRS Ferreira 1972 Fig. 64 View Figures 63–71 , 89 View Figures 88–104

planipennis View in CoL DD [1] TMSA Deschodt et al. 2015

rubripennis (Boh.) [2] NHRS Ferreira 1972 Fig. 13–16 View Figures 9–16 rugosipennis View in CoL sp. n. [2] TMSA this paper Fig. 29–32 View Figures 25–32

similis View in CoL sp. n. [1] TMSA this paper Fig. 55–58 View Figures 55–62 soutpansbergensis View in CoL DD [1] TMSA Deschodt et al. 2015

werneri View in CoL sp. n. [1] BMNH this paper Fig. 39–42 View Figures 39–46

Other species have been included in Scarabaeolus by Ferreira (1968b, 1972) [ S. ebenus ( Klug, 1855) , S. suri ( Hausmann, 1807) ], Barbero et al. (1998) [ S. interstitialis ( Boheman, 1857) , S. rugosus ( Hausmann, 1807) , S. rusticus ( Boheman, 1857) ] and Mostert and Holm (1982) [ S. scholtzi Mostert and Holm, 1982 , S. silenus ( Gray, 1832) ], however none of them conforms to the subgeneric definition noted in the Introduc- tion. Deschodt et al. (2015) included S. scholtzi on the presence of the second mesotibial spur, but noted that according to Forgie et al. (2005) this species consistently falls outside of their “ Scarabaeolus clades”. Scarabaeus scholtzi is a relatively large (about 20 mm) Pachysoma -like apterous scarab whose second mesotibial spur is slender and nearly half as long as the principal spur (as in Sceliages ), quite unlike the minuscule and rather stubby structure in Scarabaeolus . Besides that, it is a structure present in other scarabaeine tribes as well (e.g. the Gymnopleurini ), and thus an adaptation that arose more than once. As such it can be useful for utilitarian sorting of species, but not for determining relationships. We therefore do not include S. scholtzi in the subgenus.

The following synonymies have been proposed in the subgenus; their authorships are detailed below in the Species Accounts:

S. xavieri Ferreira, 1968 = S. andreaei zur Strassen, 1963

S. cicatricosus ( Boheman, 1857) , n. praeocc. = S. bohemani Harold, 1868

S. reichei Waterhouse, 1890 = S. canaliculatus Fairmaire, 1888

S. azureus Ferreira, 1952 = S. damarensis Janssens, 1940

S. vansoni Ferreira, 1958 = S. lucidulus ( Boheman, 1860)

S. bohemani Harold, 1868 = S. palemo Olivier, 1789

S. morbillosus Fabricius, 1792 = S. palemo Olivier, 1789

Deschodt et al. (2015) re-validated S. reichei , which is not accepted here because it is based on a photo of a S. canaliculatus syntype that either due to encrustation or low resolution shows no detail of elytral sculpture and judged by elevation and evenness of the ribbing could as well be identified as S. fritschi . The S. reichei holotype ( Fig. 85 View Figures 81–87 ) is an empty shell with a gaping hole in place of the metasternal process, leg joints freely moveable and the left antennal club missing, but otherwise the structure is well preserved. Zur Strassen (1967) examined the types of S. reichei and S. canaliculatus , followed Gillet (1911) and subsequent authors in synonymizing S. reichei , and characterized S. canaliculatus as having the elytra striated and intervals elevated but not distinctly ribbed. This (but not the smooth pronotal sagittal line, whose extent and elevation are quite variable) distinguishes S. canaliculatus ( Fig. 73 View Figures 72–80 ) from S. fritschi ( Fig. 74 View Figures 72–80 ), and in this regard the holotype of S. reichei ( Fig. 86 View Figures 81–87 ) matches perfectly all specimens of S. canaliculatus that we have seen. In S. fritschi ( Fig. 87 View Figures 81–87 ), on the other hand, elevation of intervals does not diminish laterally but remains more-or-less equal, the coarse punctures in their keels bear short yellowish setae, and the sharply demarcated, finely punctate striae are much wider. The parameres of these two species are identical ( Fig. 93, 94 View Figures 88–104 ) and the elytral sculpture differs in degree of development rather than in form, so in terms of population biology it could even be claimed that S. canaliculatus is only a variety of S. fritschi . However, in absence of a thorough analysis we keep the taxa separate and only point out the close similarity.

The S. bohemani = S. palemo synonymy was proposed by Janssens (1940), rejected by zur Strassen (1967), and proposed again by Deschodt et al. (2015). We maintain both species as valid the great similarity in habitus notwithstanding, because in our opinion they can usually be separated by their aedeagi ( Fig. 45–46 View Figures 39–46 vs. 88 and zur Strassen 1967: fig. 8 vs. 9). An exception is a series of 11 TMSA specimens, seven from Limpopo ( Fig. 51–54 View Figures 47–54 ) and four from Northern Cape provinces, which remind of S. bohemani in having grayish antennal clubs (see also Deschodt et al. 2015: fig. 5) but aedeagi more resembling S. palemo , with the paramere tips dorsally rounded and ventrally produced into short beaks, as in the typical western S. palemo ( Fig. 88 View Figures 88–104 ). We find naming this series premature, call it S. cf. bohemani / palemo , and theorize that it could be a transitional population in an area where the two species meet. As pointed out by Deschodt et al. (2015: 524), the question of validity/synonymy of these two taxa would best be resolved by molecular techniques.

The S. morbillosus = S. palemo synonymy can be accepted only partially and conditionally, for west African specimens that have been dissected. We examined the ZMUC types (5 ST) of S. morbillosus ( Fig. 70–71 View Figures 63–71 ) but could not dissect them, and we have no knowledge of the MNHN types of S. palemo . In this regard, we had to rely on zur Strassen’s (1967) work and his subsequent identifications of S. palemo , but they unfortunately did not answer the question of identity of this species because his drawings of S. palemo aedeagus ( zur Strassen 1967: fig. 8) do not match aedeagi that we extracted from two TMSA specimens identified by him (in 1993) as S. palemo and described in this paper as S. ( Scarabaeolus) orientalis sp. n. ( Fig. 47–50 View Figures 47–54 ). The aedeagus figured by zur Strassen in 1967 came from a Senegal speci- men that, although not identified as such in his paper, probably is one of the syntypes (see Olivier 1789: 187–188); it has a paramere with a large, triangular ventral tooth, whereas the aedeagi extracted by us from Transvaal specimens (Frm: Rhenosterpoort, leg. L. Schulze) have only a minute, easily overlooked ventral denticle ( Fig. 50 View Figures 47–54 ). The difference is too great to be considered intraspecific, and since Olivier’s (1789) syntypes of S. palemo came from two locations as far apart as Senegal and the Cape of Good Hope, we suspect that his type series consists of two species. Fabricius’ syntypes of S. morbillosus are from “ Guinea ” (actually Ghana, see Moretto and Génier (2015: 4)), and due to a closer proximity to Senegal thus more likely correspond to the Senegal syntype of S. palemo . Conversely, the S. palemo syntype (s) from the Cape of Good Hope are more likely to correspond to S. orientalis sp. n. from Transvaal, whose aedeagus does not quite match but is very close to S. cunene sp. n. ( Fig. 37–38 View Figures 33–38 ) S. lizleri sp. n. ( Fig. 11–12 View Figures 9–16 ), S. rubripennis (Boheman) ( Fig. 15–16 View Figures 9–16 ) and S. planipennis Davis and Deschodt ( Deschodt et al. 2015: fig. 6E). Only dissection of the Cape of Good Hope type(s) can show whether our assumption is correct, as external inspection alone is likely to be inconclusive.

One feature of S. morbillosus worth mentioning is the presence of orangish pads at the proximal ends of the profemora ( Fig. 71 View Figures 63–71 ). Since they are located on the dorsal side this observation is purely accidental, made possible only by the preparation style of Fabrician specimens ( Fig. 70 View Figures 63–71 ). Whether it does have any taxonomic significance is unknown to us, as due to a small number of specimens, most of them borrowed, we could not reposition or detach front legs for clear observation of the femora.

In dorsal view, the parameres of Scarabaeolus appear symmetrical because the ventral tooth does not extend far enough laterally to show. The asymmetry of the parameres becomes obvious only in ventral view, except for S. nitidus where in dorsal view the tip of the right paramere curves inward and overlaps the tip of the left paramere (in S. bohemani and S. palemo this is apparent only in ventral view). Apart from this exception the dorsal symmetry is consistent throughout the subgenus and accounts for a relatively high degree of similarity, with species-level differences in slenderness/stockiness of the parameres and in their tips, which may be truncate, inflated, bent laterally, dorso-ventrally slanted or ventrally produced into short beaks. Dorsal symmetry is common in the nominotypical subgenus as well, but usually the parameres are symmetrical also in ventral view, which is not the case in Scarabaeolus . The ventral asymmetry is thus added to the subgeneric characterization noted in the Introduction.

Scarabaeus obsoletepunctatus Balthasar ( Fig. 67–68 View Figures 63–71 ) is based on a somewhat worn and faded female that lacks both antennal clubs, has only one mesotibial spur, and resembles S. bohemani ( Fig. 43–44 View Figures 39–46 ). However, our examination shows it to be a valid species, because in contrast to S. bohemani it has denticles at bases of three rather than just two proximal protibial teeth, lacks a striola of punctures along the pronotal base, and the medial lobe of the base extends entirely over the scutellum . It bears a typed label “Benguella”, which regardless of whether it means vicinity of the city or the province at large is roughly 300 km north of the Namibia border. We are aware only of the holotype. Deschodt et al. (2015: 521) list also northwestern Namibia in their key, but do not provide concrete records.

We examined 17 specimens (15 GWPC, 1 NMPC, 1 BMNH) from “ Namibia, 60/ 80 km N of Aus, 9–10. XI.2006, Werner & Smrž leg.” that do not differ in any regard from S. ( Scarabaeolus) megaparvulus Davis and Deschodt , except that contrary to the original description all the specimens have two mesotibial spurs. We therefore list that species as having two spurs and suggest that the type material be re-examined.

A species hitherto not included in the subgenus is S. funebris (Boheman) , which its describer compared to S. morbillosus Fabricius. We find the comparison fitting and see nothing in the distribution and morphology of S. funebris ( Fig. 63 View Figures 63–71 , 102 View Figures 88–104 ) to prevent its inclusion in Scarabaeolus . Its inclusion is supported also by the aedeagus, which, except for being slenderer, closely resembles those of S. similis sp. n. ( Fig. 57–58 View Figures 55–62 ) and S. kochi Ferreira ( Fig. 98 View Figures 88–104 ).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Scarabaeinae |

|

Tribe |

Scarabaeini |

|

Genus |

Scarabaeolus

| Zidek, Jiri & Pokorný, Svatopluk 2018 |

cunene

| Zidek & Pokorný 2018 |

fragilis

| Zidek & Pokorný 2018 |

krugeri

| Zidek & Pokorný 2018 |

lizleri

| Zidek & Pokorný 2018 |

namibensis

| Zidek & Pokorný 2018 |

orientalis

| Zidek & Pokorný 2018 |

rugosipennis

| Zidek & Pokorný 2018 |

similis

| Zidek & Pokorný 2018 |

werneri

| Zidek & Pokorný 2018 |

andreaei

| Zur Strassen 1963 |

karrooensis

| Zur Strassen 1961 |

knobeli Fer.

| Ferreira 1958 |

gracai Fer.

| Ferreira 1952 |

inquisitus Pér.

| Peringuey 1908 |

anderseni Wth.

| Waterhouse 1890 |

bohemani Har.

| Harold 1868 |

palemo Oliv.

| Olivier 1789 |